LIVE: Die andauernde Nakba und die Rolle der Linken in Deutschland

Watch the event here / Sehen Sie sich die Veranstaltung hier an

The Left Berlin

03/05/2022

Watch the event here / Sehen Sie sich die Veranstaltung hier an

The Left Berlin

03/05/2022

Lawyer, local councillor and anti-racist activist Elif Eralp on voting rights, Deutsche Wohnen & Co Enteignen and mobilising non-Germans

Phil Butland

01/05/2022

Hello Elif. Thanks for talking to us. Could you start by introducing yourself? Who are you and what is your political background?

I’m Elif Eralp. I’m 41 and come from Hamburg. I’m from a socialist family – that was the reason my parents came to Germany. My mother was 8 months pregnant with me when she came here. My parents took me to various demonstrations. Particularly important were the demos after the racist attacks in Mölln and Solingen.

I started in the anti-nuclear power movement in Hamburg, then the Berlin anti-racist group Allmende. That was when the Sarrazin debate was very strong. We also did a lot around gentrification and forced evictions. As a small organisation we were also evicted. I also strongly supported the Kurdish movement, for example in the HDP election campaign.

In 2017, I joined Die LINKE because of the debate around migration, to strengthen the progressive forces in the party. 2017 was also the first year that the AfD came into the Bundestag. I helped build a network of migrants in the party – Links*Kanax. We were strongly engaged in the debate about open borders.

We wanted to let people hear the voice of people affected by racism and ensure that people with a history of racism are not pushed around. We observed that we were unfortunately a very white party, and wanted to change this. Links*Kanax works with extra-parliamentary anti-racist and migrant movements. We are trying to connect the dots and to motivate people to engage themselves for the party so that it becomes more diverse.

Last September, you were voted into the Berlin parliament. What are your impressions so far of the Red-Green-Red government in Berlin?

From the beginning there was a very difficult discussion with an SPD under Giffey, which has followed a different course to the last Red-Red-Green government. This SPD is clearly aiming at conservative milieus and CDU voters, and carried out a very problematic election campaign – emphasizing Law and Order, and criminalising migrant milieus with the so-called “Clan Debate”

The social balance of forces is unfortunately difficult to change, even though we won the Volksentscheid. But DWE has managed to popularise an ur-Left radical subject which attacks the social structure and capitalism so much that people are prepared to support it

The initial conditions were not very good for a Red-Green-Red coalition. Added to that, die LINKE lost responsibility for city development. This was a problem for Deutsche Wohnen & Co Enteignen (DWE) as the Greens were unclear on the referendum, and the SPD opposed it. But for us, it’s the most important issue of all.

But I also see opportunities, and believe we should wait a year to see if we reach a breaking point. If DWE is ignored, we must talk about exit scenarios. But now we’re in, and my experience is that we can change things and make progress. In the coalition agreement, the section on participation, migration and anti-discrimination is very good.

Having said this, senators are already not respecting the ban on night deportations. But there is definite progress on voting rights. So there are successes, but also failures. There is a continual fight in many areas, particularly regarding domestic policies like housing and migration.

Let’s start with the simplest question about voting rights. Who can vote in Berlin and who can’t?

For the general and council elections, and for Volksentscheide, only German citizens are eligible to vote. On a municipal level, EU citizens can vote for the BVV, but not third country nationals. This means that 20% people in Berlin are excluded – in my constituency it’s over 35%, though some of them can vote in the BVV elections.

You are providing legal advice for the new People’s initiative Demokratie für Alle. It the moment, the campaign is trying to collect 20,000 signatures. What happens then?

In the coalition agreement, the Berlin government has promised to initiate a Bundesrat initiative to change the constitution, and also to see what is legally possible on a local level. Although the national constitution currently refers to “the people”, not “the German people”, in practise it currently only applies to German citizens.

After decades of migration, Germany should be finally recognised as a country of migration. The general public has become, in general, more willing to accept that migration and a diverse society are the normal state of things. This is why I think that German states should be able to extend the vote to people who do not have German citizenship.

The demand for voting rights is very old. The Gastarbeiter generation – the generation of my parents – also made this demand. The People’s Initiative is applying more pressure from civil society. I hope that the Berlin Senat grants voting rights, but if this doesn’t happen, I and my party will support a referendum with all our powers.

Very many people in my constituency are very dissatisfied. Some don’t engage in politics, saying “I don’t have a vote anyway”. This is why it’s great to involve more people around issues like high rents and structural racism. We need to get more people involved and to demand that things change.

The right to vote is a basic democratic right, so that everyone who is affected by these laws can vote to change them. It’s unbelievable that so many people were not allowed to vote in the Volksentscheid. Many people with a migration background are affected by forced evictions, but they’re not allowed to vote on something that could solve this.

What about the demand for voting rights for 16 and 17 year olds?

The People’s Initiative also calls for voting rights from 16. Berlin is able to grant voting rights to 16 and 17 year olds on its own. In the constitution voting at 18 only applies to the Bundestag and not to regional elections. We are already talking with the opposition FDP, who also put the demand in their election manifesto. FDP support is necessary to get the two-thirds majority necessary to change the regional constitution.

What do the other parties in the Senat say about voting rights for non-Germans?

In Berlin the coalition partners are in agreement. The lack of voting rights for non-Germans is a form of discrimination. This is written in the coalition agreement. We have committed ourselves to find ways of improving active voting rights for non-Germans on a regional level.

There are legal complications following a court decision made in Bremen in 2014. But Bremen is only one of 16 constitutional courts. I’d have preferred it if the Berlin Senat had said we’ll implement it anyway, but the coalition decided that because it is legally unclear, we’ll first assess what is possible.

We have also agreed to bring an initiative into the Bundesrat. We hope to apply so much pressure – together with actors from civil society like the People’s Initiative – that change will come on a national level. But it’s not in the national coalition agreement so it might not happen.

In Berlin we also have the problem that the Berlin constitution explicitly refers to German citizenship in its section on voting rights. This means that we need to change the constitution, which needs a two-thirds majority. We must still try to win over one of the other democratic parties, and voting rights for non-Germans was not in the manifestos of the FDP and CDU.

This is where the People’s Initiative is very important for applying pressure, not just on the governing fraction but also on the opposition.

Many people are sceptical, both about legal change (after the Mietendeckel) and whether referenda will be implemented (after DWE). How can we be so sure that a Berlin government will implement these changes? The precedents aren’t great.

The DWE Volksentscheid was not a binding draft law, and was dependent on the political commitment to implement it. But for me as a councillor, a citizen and a member of the governing fraction, when 60% of people vote for something, it’s binding.

In the case of voting rights, I am very hopeful, because it’s there clearly in the coalition agreement. We have the political commitment from the SPD, Greens and LINKE that we want to extend voting rights,

But getting the FDP or the CDU on board won’t be so easy. For this reason I hope that there will be massive pressure on the opposition fractions so that we can implement the change.

How can people who are not sitting in the Senat apply pressure so that their demands are respected?

This is what I’ve been doing as an anti-racist activist for many years, and what I’m continuing to do. Organise meetings, take to the streets, have rallies and demonstrations around the issues. Publicise it all on social media. Everyone can collect signatures, whatever their nationality. Many people with a migration background collected signatures for DWE.

The responsible councillors in the LINKE fraction are also going to have talks with the People’s Initiative. There are also many migrant organisations working on publicising the issue. There are so many different ways that people can take part, even if they’re not negotiating with the political decision makers.

Talking about DWE, at the moment there’s a great helplessness among people who in the last two years have done little else but collect signatures, organise meetings, etc. How can you convince such people that it’s worth it? I know people who are still ready to do something, but are simultaneously asking whether the system will allow it.

Changing the voting age and socialisation are milestones. Socialisation is such a serious attack on capital that if it happens it would be a historic event. That’s why it is absolutely worth fighting for. The socialisation of the housing market is central to me because if we implement it it would finally mean homes for people who live in them and not for making money for a few. The goal is so great that it deserves a great deal of effort.

But I can absolutely understand frustration. I’m also pretty frustrated, although I’m part of the process. It is frustrating to know we won, but we’re not sure whether it will even be implemented. That’s down to the balance of forces, which also lie with economic cartels, real estate traders, and political decision makers who are partly interwoven with the real estate lobby, by whom thy are financed.

The social balance of forces is unfortunately difficult to change, even though we won the Volksentscheid. But DWE has managed to popularise an ur-Left and radical subject which attacks the social structure and capitalism so much that people are prepared to support it – even some CDU voters, because of the urgency of paying too high rents.

It is a massive victory which affects other European countries, which are trying something similar, and in other German Bundesländer like Hamburg. There are many examples. I’m convinced that it will be implemented.

I’m trying to take the Commission as a chance, though much depends on who will be in the Commission. There’s also justified criticism of its way of working. But I think that we have not lost this fight. As it is such a large subject that is so widely discussed that I hope that it’s still a great victory. I hope that we will win.

One final question. The main public of our website is non-Germans in Berlin – one in four Berliners don’t have a German passport. You already said that many people feel excluded from German politics, because of language, voting rights, whatever. How can people without voting rights practically engage in politics here?

There are many different ways. My father is very engaged, although he has no voting rights. There are various alliances, extra-parliamentary initiatives, action groups against racism. There’s Fridays for Future, alliances against rent madness, the Alliance for sexual self-determination. For each socially relevant subject there’s a group where you can get active.

Our party wants to being together all milieux – not just the climate movement, not just the anti-racist movement, not just the tenants’ movement. We want to bring all these subjects together and to address the difference milieus and groups. That’s why I find it important that people get active in parties which have a complete social concept, and doesn’t just look at individual issues, For us, this complete social concept is democratic socialism, even though we want to implement many reforms on the way.

As well as parties, it’s great if people engage in People’s Initiatives. This is one of the few available elements of direct democracy, even though it can be very frustrating, especially if you’re not allowed to put a cross on a ballot paper. But you can collect signatures, you can make publicity. This is why expropriation has become an issue in a neoliberal country like Germany. It has been achieved by people who are not all German citizens.

2022’s presidential elections were neither a victory nor a failure for the left – because the fight is not over yet.

Florent Marchais

30/04/2022

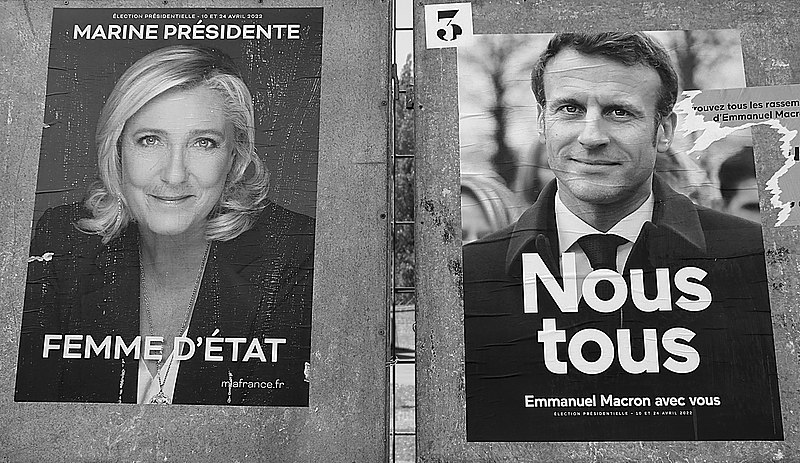

The 2022 French presidential elections in April reconfirmed the existence of an electoral left ready to take power in France. Now, sights are set on the June legislative elections; the Popular Union, the strongest force on the French left, seeks to impose parliamentary “cohabitation” to enact ecosocialist domestic policies and counter Macron’s second term.

The First Round

The first round of presidential elections were held on April 10th. Neoliberal incumbent Emmanuel Macron (27,84%), his two-time far-right challenger Marine Le Pen (23,15%), and left-wing firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon (21,95%) garnered the highest number of votes, confirming two things: the existence of three main voting blocs that dominate the French electorate and the obliteration of traditional parties like the Republicans (4,78%) and the Socialist Party (1,75%). Mélenchon’s score was surprisingly high given the barrage of media attacks he’s suffered since 2018 due to his critical tone and vociferous opposition to neoliberal elites and unfair if not calumnious characterizations as a supporter of anti-American dictatorships from certain Atlantist factions of the center-left. Final days of polling show him at only 17%, yet the innovative campaigning of “l’Union Populaire,” (including door-to-door canvassing, town-hall meetings all across France, a rally with simultaneous appearances in 12 cities using holograms, and a focus on bread-and-butter social and ecological issues rather than negative attacks on center-left opponents), mobilized hundreds of thousands of supporters to attend in-person events, and trained tens of thousands of new committed activists.

Keeping in mind that 5% of votes are needed to qualify for public campaign funding, if only one minor center-left candidate had dropped out in the last days leading up to the election (as the Greens only received 4.63% and the Communists 2.28%), this would have given Mélenchon the 1.2% more he needed to pass to the second round. As Jacobin Magazine’s David Broder put it, “those who voted Green or especially for the post-Communist PCF should ask themselves whether it was worth it.”

In this scenario, Marine Le Pen would not have continued to the second round, which would have allowed for a productive debate between the top two candidates on such issues as ecological planning and re-industrialization, peaceful and anti-imperialist foreign policy, rebuilding public services, and the like. Instead, dialogue centered around whether wind turbines should be disassembled, if Muslim women should be allowed to wear hijabs in public, and whether France respects the police enough – all topics of Marine Le Pen’s program. Two weeks of campaigning could have prevented the pitfalls of the neoliberal vs far-right duel that Western Europe and North America are dealing with all too often, one election cycle after another.

Demographic Shifts in the Electorate

It’s worth noting that Mélenchon won the most votes among young voters, the educated lower-middle class, and the most precarious citizens who earn under 900 euros a month. Macron’s performance was most effective among the oldest bloc of voters who are retired. The rural/urban divide turned out to be once again one of the clearest indicators of the probability of voting for the far-right, with economically disadvantaged rural and peri-urban areas voting more for Macron than for Le Pen in the second round. The Mélenchon electorate is also particularly strong in the working-class suburbs of large metropolitan areas.

While Mélenchon won majorities in overseas departments like Martinique, Guadeloupe, and French Guyana in the first round, Marine Le Pen won large majorities (accompanied by much abstention) in the second. Their predominantly Afro-Caribbean populations have been gravely affected by high unemployment and ecological degradation. These areas are so neglected by Macron and preceding governments, that within two weeks, the anti-system vote transferred to Marine Le Pen – a xenophobe with no real policies to offer French overseas departments.

The Second Round

A poll from late 2020 showed that 80% of French voters said they did not want to see another Macron vs Le Pen duel, yet the same spectacle from 2017 was repeated. The second round of presidential elections on April 24th saw the re-election of Macron with 58.5% of the vote – with 42% of his voters turning out only to reject far-right candidate Marine Le Pen. Moreover, abstention was at its highest since 1969.

The Benalla affair, McKinsey Gate, the use of private counsels from BlackRock to reform retirement pensions, and a number of other scandals affecting Macron, his ministers, or his associates merit reflection. They also provoke sympathy for anti-system voters and abstentionists who joined the Gilets Jaunes movement in 2018 because they’d had enough of the lies and manipulation used to make ordinary French citizens swallow the pill of neoliberal reforms that break apart the fabric of social services and labor protections won through the struggles of the working class.

Of course, Marine Le Pen continues to be a danger to the already dysfunctional and hyper-centralized institutions of the French republic. Her Citizens’ Initiative Referendums, a proposal of the Gilet Jaune movement that would allow the public to abridge and propose laws directly, did not camouflage her party’s fascist history, its dependence on Russian and Hungarian banks, nor its admiration for those countries’ authoritarianism. She deserved to be defeated and cast away from public light, since her dangerous xenophobia would only repress the working class.

But five years of Macron also paved the way for repression: between the aggrandizement of the police state, increased support for the military-industrial complex, a degradation of democratic norms, or the adoption of far-right talking points by Macron’s ministers, it is increasingly difficult to perceive the difference between Macron and the most reactionary edge of France’s right wing. On top of this, even increasingly ecologically conscious “middle” class voters have reason to feel betrayed by Macron – he was condemned by the Council of State for climate inaction for failing to meet emissions objectives, and rejected or watered down 90% of the propositions brought forth by the Citizens Convention for the Climate.

The legacy of Macron’s first term will certainly continue into his second if a strong left-wing parliamentary opposition is not built in time for the legislative elections in June this year.

Looking Towards the Legislative Elections

In a sense, France’s 2022 elections are not finished – there is a “third round.” A series of legislative elections are set to take place on June 12th and 19th and will determine whether the incumbent president has a parliamentary majority and a prime minister to support his policies. Under the semi-presidential constitution of the Fifth Republic, the president nominates the prime minister, whose role is to implement domestic policies and direct the Council of Ministers. An oppositional majority could hypothetically force Macron to choose a prime minister from their majority in the National Assembly.

The bet taken by l’Union Populaire is as follows: each electoral constituency should vote for their own candidates in order to form the oppositional majority necessary to name Jean-Luc Mélenchon prime minister. Is this an unreasonable bet? In some ways, yes. Most constituencies will be more easily won by large parties and rural constituencies will be overrepresented in relation to their population. But the left has never won with thoughts of defeat. “Mélenchon as prime minister” is a slogan that re-mobilized thousands of militants – both veteran activists and fresh new faces. Given the national media attention and the will of activists to remain civically engaged, there is no reason why Mélenchon and l’Union Populaire should shoot for lower than 50% of seats (289 seats for an absolute majority) in the National Assembly. After all, the left does not exist to simply advocate for workers, the environment, and social justice, but to govern in order to make material changes toward that end.

Projections show that l’Union Populaire is leading in 104 constituencies and in the second round in 423. Polling shows that voters are craving a strong left led by l’Union Populaire. Furthermore, the objective of winning a seat at the table as prime minister also allows voters to make the connection between local legislative candidates of l’Union Populaire and its former presidential candidate, Mélenchon, who has immediate name recognition and renewed popularity.

Inter-party Discussions

Following the first round, l’Union Populaire proposed discussions with parties to the left of Macron’s “La République en Marche,” which include the Greens, the Communists, and the New Anticapitalist Party. Talks are taking place this week to center l’Union Populaire’s demands in the left’s bid to the electorate; “l’Avenir en Commun” (The Future in Common) is a comprehensive program with around 700 unique policy proposals, and will be at the heart of what the left is promising voters. This is only natural, since Mélenchon’s recent electoral score far outweighs those of other parties. These discussions will also be used to reach an agreement so candidates do not compete against each other in the same constituencies. The productive nature of this recent dialogue is already evident: a new accord was drawn up on April 28th between La France Insoumise and Generation.s, a small pro-EU left wing party created by 2017 candidate Benoit Hamon. This shows a new willingness to resist the neoliberal EU treaties constraining pro-social and ecological policies. Discussions with the Parti Socialiste are less productive, however, who are not so open to the terms and political policies of l’Avenir en Commun. Regardless of what federation is created, non-negotiable left-wing policies will inevitably remain anchored to the movement’s program.

We Have a World to Win

Election-watchers who tuned in to April’s presidential rounds should stay tuned for the “third round.” France presents a unique opportunity for the global left: there is reason to be hopeful that this major “Western” power, with its long history of monarchic rule and colonial exploitation of Western Africa, the Maghreb, Indochina, and the like, might one day be reclaimed by its working class for the causes of labor rights, respect for the environment, and peace and diplomacy abroad. If the left can win in France in our lifetime, it is possible for the left to win anywhere.

Amazon workers on Staten Island are voting on a union through April 29th. What does their struggle mean for the labor movement?

Ella Teevan

27/04/2022

This month, Amazon workers on Staten Island made history when they voted to form the first ever union at the notoriously anti-worker logistics behemoth. Right now, workers at a second Amazon facility on the same campus are voting on whether to unionize. The Amazon Labor Union (ALU), the scrappy, independent union who organized the JFK8 warehouse, and its charismatic leader, Chris Smalls, are about to face their first real test after their monumental upset victory.

It’s hard to overstate the magnitude of ALU’s struggle. For one, the emergence of unions at Amazon, the US’s second-largest private employer, has profound implications for the balance of power between the labor movement and capital. Reporters on the labor beat have called it the biggest victory for US labor since the 1997 Teamsters strike, since the Reagan era, or even since labor’s high water mark in the 1930s. Furthermore, ALU is shaking up time-tested organizing maxims that, until a few weeks ago, seemed like common sense. As this high-stakes struggle unfolds, here are five things to watch for.

1) Is the JFK8 victory a one-off, or will it inspire a union wave like we’re seeing at Starbucks?

On April 1, workers at the JFK8 warehouse clinched their victory 2,654 to 2,131, with 8,325 eligible voters. From April 25 to 29, about 1,500 workers at the nearby sorting center LDJ5 will vote on whether they want to join ALU. The scale of LDJ5 is smaller, and workers’ demands aren’t identical; whereas warehouse workers are facing grueling twelve-hour shifts, the mostly part-time workers in the sorting center just want enough hours to pay the bills. But despite these differences, the second vote following close on the heels of the first has the opportunity to create a narrative of a union snowballing at Amazon – if the workers vote yes. Chris Brooks of the NewsGuild of New York calls this phenomenon “momentum organizing”: “Workers are in terrible conditions all over the country and when they see a public example of a group of people in a similar situation taking action to better their situation, it encourages them to do the same.”

There are reasons to be optimistic that Amazon workers will secure a second victory. New York has high union density, at 20%, compared to just 6% in Bessemer, Alabama, where Amazon has successfully suppressed a union vote twice. This means more workers know first-hand the benefits of being in a union, from their family members or friends. In addition, the US is witnessing a union wave at Starbucks, showing that, in 2022, conditions have made it possible for unions to spread. Labor scholar Ruth Milkman points out a few of the conditions that might encourage Amazon workers to unionize: first, the recent rise of the college-educated left in the US has enabled union victories among journalists, academics, and even at Starbucks (although, she says, the Staten Island victory eclipses any of these smaller wins). Second, a tight labor market means that workers can feel more comfortable taking the risk of unionizing; if they’re fired, they’re well-positioned to get another job. Finally, Amazon’s own brutally repressive tactics, like electronic surveillance and automatic firings, might be the best motivator for workers to vote for a union.

However, we shouldn’t underestimate Amazon’s union-busting for a minute. The company spent $4.3 million on anti-union efforts in 2021. They subjected Staten Island workers to tried-and-true boss tactics like captive audience meetings and anti-union consultants prowling the shop floor and telling lies to workers. Labor Notes’ Luiz Feliz Leon has detailed how Amazon is playing dirty at LDJ5, even blaming one worker leader for the suicide of another worker.

So, will the LDJ5 vote be the second in a coming wave of Amazon unionizations? Workers and leftists (and Amazon) will be watching closely to find out.

2) ALU’s organizing approach was deeply unorthodox. Does that mean we throw out what we know about organizing?

If you’ve followed this story, you’ve probably heard about ALU’s unusual tactics. They eschewed traditional house visits, instead favoring conversations in breakrooms and at public bus stops. They made savvy use of TikTok and Telegram. They reached out explicitly to workers of color and immigrants. They even handed out marijuana once. ALU made strategic decisions that defied standard labor organizing practices, like going public before their organizing committee was established, and filling for an election with the NLRB with the bare minimum of cards signed – 30% – when veteran organizers usually wait until they have 70% or 80%.

And you’ve no doubt heard about ALU leader Chris Smalls, whose story is now famous: Amazon fired him after he led a walkout to protest the absence of pandemic protections. The company then aimed to discredit the union effort by painting Smalls as “not smart or articulate” – a smear Smalls turned around to make himself a martyr for the workers’ struggle. Many of the other worker leaders in the struggle were also new to labor organizing, although some salts (experienced organizers who infiltrate a workplace with the goal of forming a union) were present.

But perhaps the most noteworthy feature of the ALU fight was the nature of ALU itself. They remained intentionally independent from the traditional unions that might organize the logistics sector, like the Teamsters, or the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU), who attempted to organize Amazon workers in Bessemer, Alabama last year. According to workers, this gave ALU an advantage not available to these larger unions: when Amazon and their professional union-busters attempted the standard boss tactic of “third-partying” the union, claiming that workers would have to contend with the whims of a new institution that had its own agenda, ALU could easily counter that everyone in the union worked in the warehouse. The union would fight for the workers’ interests because the union was the workers.

However, despite the ways they broke from labor norms, it’s important to note that, in some respects, ALU did follow tried-and-true labor organizing practices. Labor Notes’ Luis Feliz Leon, in an interview with ALU Vice President Derrick Palmer, concludes that the workers clearly mapped their workplace and tracked what percentage of workers supported the union, even if they didn’t use “organizing lingo.” They identified which workers had sway in their departments and on their shifts and worked with those people to bring in the people who trusted them – something that organizer-writer Jane McAlevey would call identifying organic leaders. So despite ALU’s particularities, their victory doesn’t give us permission to take shortcuts – organizing will always take building deep relationships and trust with the majority of workers at a workplace.

Furthermore, it’s worth asking whether tactics like filing for an election with only 30% of cards signed would be effective in other times, locations, and conditions. Some labor thinkers see the ALU victory as a vindication of the “metro strategy” – a plan to focus organizing Amazon facilities in a few major cities like New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles where the company is concentrated, and where unions enjoy broad support. However, that doesn’t mean ALU’s tactics will work universally. To attempt to replicate ALU’s strategy somewhere like Bessemer would be ignorant of the differences in conditions between a blue-state metropolis and a deep red, right-to-work state.

For ALU, being an independent union had distinct advantages. Does this mean it’s time to give up on institutions like the Teamsters in favor of independent unions with very little funding? In a word, no.

3) Where do the big institutions of organized labor come in?

To organize broad swaths of workers at a virulently anti-union mega-corporation, it will take more than ALU, or a hundred institutions like it. It will take more power than organized labor and the Left have in 2022. Labor scholar Shaun Richman puts it in stark terms:

“Some people may look at the success of ALU, and at the continuing frustrations of RWDSU’s efforts in Bessemer, and draw the conclusion that organizing independently of the established unions is a key to success. That would be a mistake. Only a major international union can muster the resources to take on Amazon across the continent and win a coast-to-coast union contract covering workers at all fulfillment centers.”

For many in labor and on the Left, the union best-positioned to organize Amazon is the Teamsters. Workers at the powerful, highly-resourced union recently elected a democratic reform slate after decades of entrenched leadership by the Hoffa administration, and new president Sean O’Brien has pledged to organize Amazon. This move aims not just to improve working conditions for Amazon workers, but to shore up the power that the Teamsters have at UPS and DHL – a power that the mere existence of Amazon’s low-wage, non-union jobs threatens. O’Brien has indicated that the Teamsters will follow the metro strategy, where they are most likely to win elections, and use the support of elected officials.

However, given the diminished state of organized labor in the US, even the Teamsters – in coalition with other possible partners like the AFL-CIO and SEIU – challenging Amazon is no guarantee. As Amazon workers continue to organize, Amazon will use its vast resources and the US’s unique union-busing industry to fight them at every turn.

4) Will the first victory stick, or will Amazon overturn it?

Of course Amazon is doing its utmost to thwart ALU’s victory at JFK8. Its first tactic is to overturn the vote. The company has filed 25 objections with the National Labor Relations Board and challenged the vote on a handful of other procedural grounds. Even if the objections are overruled, Amazon is likely to use them as an excuse to delay negotiating a contract.

Secondly, there’s the contract itself. Delaying on a contract for many months is standard boss practice; it can kill the momentum that comes out of a union vote. The Lever’s Matthew Cunningham-Cook points out that, according to what little data we have, about a quarter of union victories don’t lead to a first contract. He goes on to lay out what it will take for ALU to lock in their contract:

“Ultimately, though, the key for ALU is to build momentum for a strike. This would require organizing at least 60 percent of the more than 5,000 workers who either did not vote for the union or voted against it — as well as everyone who voted for it — to take a massive escalation. Without a credible strike threat from ALU, Amazon will not agree to a contract. Full stop.”

So is the JFK8 victory the biggest milestone for labor since the 1930s – one that will spark a wave of unions at Amazon and eventually a nationwide contract under the Teamsters, shift the balance of power toward labor, and move the needle toward a fundamental shift in the economy? Or will Amazon’s machinations turn the Staten Island David-and-Goliath struggle into an attempt that fizzles out? That depends, in part, on the actions of organized labor and the Left.

5) What’s the relationship between Amazon organizing and other arenas of struggle on the Left?

While workers’ struggles are central to the Left’s project, they exist in an ecosystem that also includes political organizations, movements, and elected officials. The Amazon workers’ struggle provides perhaps the highest-stakes challenge yet for the US’s renewed post-2016 Left to support, and integrate with, a major labor organizing effort.

New York City is an opportune battleground. The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) have their largest chapter and strongest electoral presence there, with six state legislators and two city council members, along with DSA-endorsed Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) and Jamaal Bowman in the US House of Representatives. Already, on April 24, Bernie Sanders and AOC held a rally with Amazon workers ahead of the LDJ5 vote.

According to some in DSA, the role of socialist elected officials should be to use their office to organize people into struggles like the one at Amazon, providing credibility, media attention, and support. NYC’s Socialists in Office have an unprecedented opportunity to throw their weight behind the Amazon fight – and the results will show us what the relationship between elected socialists, DSA, and militant worker struggles can look like.

As Amazon workers cast their ballots, the labor movement and the Left should pay close attention to the particulars of this struggle in order to inform our strategy. The fight to organize Amazon won’t be short or easy. But it’s one we can’t afford to lose.

Community organizer Fatherr Flavie L. Villanueva, SVD explains how the “War on Drugs” has made killing a business in the Philippines

Alexa Aranda

24/04/2022

Since 2016, Philippine President Rodrigo’s anti-drug policy declared as a ‘war on drugs‘ has resulted in thousands of deaths and ongoing grief. Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic this has exacerbated a longstanding problem: that of the exhumations of ‘apartment graves‘. As leases expire after five years, it affects victims of the ‘war on drugs’ – which Amnesty International has called a ‘war on the poor‘ with heightened urgency. For this reason, Program Paghilom offers a space for mourning and supports families in acquiring a dignified reburial.

Father Flavie L. Villanueva, SVD, is a missionary priest of the Divine Word and is committed to the psychospiritual support and empowerment of communities affected by the ‘war on drugs’. Since 2016, he has organized Program Paghilom and Kalinga programs that follows the vision of recreating and empowering lives. Kalinga’s program consists of acts of care integrated in a dignified, systemic, and holistic manner.

Thank you very much for your time and efforts, Father Flavie. When did your community rehabilitation program begin?

In 2016, newly elected President Duterte declared his anti-poor drug policy, and the killings began. At first, in the back of my mind, I tried to find a compromise, but by August I was convinced that I had not elected this man. It was the first time in history that we experienced such chaos amidst the so-called “war on drugs”. I am now running the Paghilom program with the inspiration of Kalinga. KALINGA is an acronym and stands for: Kain-Aral-LIgo-naNG-umAyos (Eating, Learning, Bathing, Welfare). It is all DIY. There was no pattern or model for how to feed, wash, and how to care for the widows and orphans of the “war on drugs” in a holistic, dignified, and systematic way.

I believe that there is indeed a drug problem, but it is not the main problem of the country. The drug problem is primarily a health, medical and clinical care issue. But the “war on drugs” is misdiagnosed as a ‘peace and order‘ security problem, where the police are used to killing. If you are going to treat it as a crime problem, please start with the drug cartels and don’t blame the marginalized.

You’ve now already talked about a misdiagnosis of the “war on drugs” as a security problem instead of a health problem. How is police violence related to extrajudicial killings (EJK)?

Definitely, it was the PNP (Philippine National Police) that weaponized the anti-drug task forces of Oplan Double Barrel or Oplan Tokhang. Through them, a culture of killing, as well as an economy of violence and killing, has developed. The military also plays a role, but mainly in the provinces. Perhaps I could add that all of this is a formula of EJK from Davao, from when Mr. Duterte was still mayor, that carried over from the local to the national level.

It is a painful reality that with every person who is shot, a murderer is born. I think even if Duterte was not our president, then the killings would not stop. This is because of the market that this has created, the culture that is embedded in the oral and written order. All this has created a cycle of violence and death that is so deeply embedded in the PNP.

Can you elaborate a bit on how an ‘economy of killings’ has developed?

There is a market for it for people who want someone killed. The police tag a prisoner who is under their care and exploit that prisoner by making them false promises. For example, they say: “if you kill this person, you’ll have a shorter sentence to serve and you’ll be under my protection.” If a murderer told me I was on a drug watch list, he would extort money from me because I want to live. There is something called palit-ulo in Tagalog, a “head swap”. The condition is that I have to point to someone who will exchange my “head.”

Would you say that this is a crude form of corruption that extends to the killings?

It goes further than corruption. Killing has become a business in its own right, a viable product. They have created their own arena with new types of capitalists. This regime blamed the rich people of old, the aristocrats, imperial Manila. They have created their own imperialism and their own capitalist movement themselves. That is why it is so functional, because the lackeys benefit from this political arena.

What civil society aspirations emerged during this period?

Let me try to name some glimmers of hope. First and foremost, we have to acknowledge how the bereaved, mostly widows, are doing their best to respond. How do they draw strength? I think of the stories of widows and orphans who have decided to wake up and get back on their feet, even though they have lost their loved ones and providers. They pick up trash for a fraction of a dollar to put food on the table. I think of the orphan who lost his parents before his own eyes and provides for his siblings.

I see in these stories a reason for hope, because justice is beginning to take shape. I will not define justice simply as a victory in court. Justice, to me, means seeing these widows heal every day and carry on despite their pain; seeing children and single parents bring about social change in their communities. The only way to respond to this evil is to join hands.

What are the difficulties of exhuming graves of those affected by the “war on drugs”?

It will be important to document the exhumations because it is history in the making. First of all, why cannot a person be given a permanent burial, to begin with? Why do they have to rent so-called apartment graves? This is about poverty as a social sin, which becomes paramount in the issue of extrajudicial killings.

Second would be the stigma, so we have difficulties letting people know that it is the body of a former victim of the ‘war on drugs.’ Another issue would be sometimes the lack of understanding towards cremations of the families themselves. For some, it is better to put their loved ones into a sack when the lease on the grave expires rather than to have them cremated and buried in a dignified place.

There is also a lack of interest from people who do not want to participate in this endeavor, due to safety concerns and pandemic guidelines. The final issue is the cost of cremation, which costs PhP35,000. This includes the permits, documents, and transportation. The urn accounts for another PhP10,000, to which the fee for transferring the ashes is added in the meantime.

What was it like for you to accompany those involved in the exhumations?

It’s like reliving the memory of the dead, which continues to be painful for the bereaved and leaves even deeper wounds. From the grave, however, there could also be some forms of liberation of the truth, as well as coming to terms with the traumas, healing, and hope for an end to this. What happens to them is, as I say, an experience of liberating truth in the midst of pain. Inevitably, there is also the relived experience of killing.

Nevertheless, is there such a thing as postmortem dignity in these cases?

Human dignity is something that is innate, if you put it in Christian terms – imago dei – image of God, respect. When you talk about respect, you have to include two words: Truth and Justice. Poverty pushes the victims of the drug war to a level of discrimination, even treating them like commodities. We respond by opting for a more expensive but more dignified way of treating the body: A real cremation, rather than simply putting them in a bag and to be placed on an anonymous pile of bones.

A personal form of this is how the relatives experience it before their own eyes, how they come to the acceptance that helps them to find peace. They become agents of social change in their community. The experience of viewing their loved ones like this may be seen by others as retraumatizing, but we take this experience and process it together.

What does solidarity mean to you?

Solidarity comes with a fraction of a whole. Solidarity is not limited to taking to the streets. Solidarity means making the voice of reason, the voice of one’s conscience, heard, and submitting to it even if the position to be advocated for goes against the tide. The weakest form of solidarity is the donation, when it is reduced to charity. Solidarity in action means being unpopular, being ridiculed. I say it in Tagalog:

Mangahas tayong magsalita kahit tayo ay babatikusin.

Mangahas tayong tumindig kahit tayo’y papaluhurin-

Mangahas tayong lumuhod at manalangin kahit ang langit ay mistulang takip-silim.

Mangahas tayong umabot, makiramay, lumuha

sapagkat ang bawat luha ay panghilamos ng Maykapal.

[Let us dare to speak even if we are mocked. Let us dare to (resist) standing even if we are bowed down. Let us dare to kneel and pray even when the sky seems to be dimming. Let us dare to reach out, to sympathize, to weep, for every tear reveals the face of God .]

It means risking something, taking a stand, a transition from a passive, selfish state to a more empathetic, engaged, and empowered stand.

RESBAK (Respond and Break the Silence Against the Killings) is among the organizations at the forefront of raising awareness about the ongoing harm of extrajudicial killings in the Philippines. RESBAK is composed of artists, academics, and community members affected by the drug war. To support grieving families affected by the drug war, RESBAK and Program Paghilom opened a fundraising campaign for those looking to extend their pakikiramay. Your donations will at least grant victims of an unjust war a final resting place. Donors can send cash donations for the fund via Paypal, GoGetFunding, or GCash 09150172703. To receive updates on RESBAK’s projects, please subscribe to their social media page.