Al-Bashir’s men, his security apparatus–the Janjaweed militia, and the military, and the state police, have stained their hands with Sudanese blood. They ignited a proxy war, fighting for expansionist imperialist ambitions to control and compete for Sudan’s resources and exploit its geopolitical position.

About six years ago, in the second half of December 2018, Sudan’s cities rose up against the policies of privatisation and rising prices of basic goods, especially bread. Citizens of Atbara, ‘the city of iron and fire,’ burned down the headquarters of Sudan’s ruling National Congress Party, headed by General Omar al-Bashir, who had usurped power for more than thirty years.

The 19th of December was like the storming of the Bastille–the protests quickly spread to all other villages and cities in Sudan until they reached Khartoum, the capital, where daily, day and night, centralised demonstrations were held in its three neighbouring cities, Khartoum, Omdurman and Khartoum Bahr. Citizens gathered in neighbourhoods, schools, universities, official and popular football fields, mosques and industrial areas without ceasing, despite the killing, bullets, arbitrary arrests and forced disappearances.

Arbitrary arrests and enforced disappearances

After mobilising citizens for five months, from December to April, the resistance succeeded in besieging the General Command building on 6 April 2019. They then carried out a sit-in, known in Sudanese circles as the General Command sit-in, and persisted, withstanding bullets and continuous assaults. After five days the security committee was forced to arrest al-Bashir and held him in a “safe place”, and proceeded to announce the setting up of a military council to run the country for two months or more.

The resistance rejected the council and demanded full civilian rule, according to the Declaration of Freedom and Change. The security committee, which began to call itself the Transitional Military Council (TMC), stalled negotiations, while the revolutionaries refused to leave the sit-in and rejected all attempts to circumvent the demands of the revolution.

On 3 June, the security committee brutally dispersed the sit-in with excessive force, killing hundreds of people and dumping their stone bound bodies in the Blue Nile.

Despite the rising death toll, persecution, internet and telecommunication cuts, and media blackout, the Sudanese revolutionary forces regrouped successfully, calling for a million-man demonstration on 30 June 2019 in Khartoum.

On that day, the crowds exceeded expectations, as Sudanese people came out from all parts of the country and from the three cities of Omdurman, Khartoum and Bahri, and declared their rejection of military rule, and their continued struggle for freedom, peace and justice.

The Berlin conference is Africa’s renewed curse

In Berlin, the German Foreign Ministry called a conference on Sudan, where it invited Sudan’s neighbouring countries, as well as Britain and America, but did not invite a single Sudanese person. Here, they started to promote a partnership government between the military and civilians, which was against the will of the revolutionary masses. Through Ethiopia and the intervention of the African Union and IGAD, negotiations between some opportunists affiliated with the revolution and the military council resumed. These negotiations were supported by the so-called international community, and a transitional government was imposed in the name of partnership between the military and civilians, on the basis of which General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan became head of the Sovereign Council (the collective head of state of Sudan), and his deputy Mohamed Hamdan Daglo, and Dr Abdullah Hamdok became prime minister and the executive authority.

The partnership supported by the “international community”–which was rejected by a large sector of the revolutionary forces, lasted for two years, during which, the prime minister changed his government twice, adopted IMF policies, and raised subsidies for the disgruntled. They also repealed the law rejecting normalization with Israel and went as far as receiving and meeting Israeli leaders in Khartoum. This caused widespread demonstrations and protests against the policies of the Transitional Partnership Government. All these events, in addition to the obliteration of the justice files, increased the gap between the Hamdok government and the revolutionary street. The Islamists and their allies came up with new names and plans, encouraging Burhan and his deputy to overthrow the Freedom and Change Government in a military coup on October 25, 2022.

‘Down with the tenth, down with the tenth, we don’t want military officers in power.’

From the dawn of the coup, the resistance to the new coup began. People came out early in the morning from everywhere, rejecting the coup and the return to military rule. Groups of resistance youth headed to the main streets and blocked them, and some headed to the General Command, but were shot dead before they could enter and occupy the command. More than twenty unarmed peaceful demonstrators were killed that day. This made clear their bloody intention to monopolise power, which increased the ferocity and seriousness of the resistance in overthrowing military rule and breaking the evil cycle forever.

The resistance committees in the neighbourhoods led the resistance and set the overthrow of the coup as a priority and put forward the slogan “No partnership, no negotiation, no legitimacy”, and mobilised the street against the coup and weakened it completely. Under the pressure of the revolutionary street, Burhan released Abdullah Hamdok and a group of detainees and signed a new agreement in which Burhan promised to return to the civil transition path and correct the course of the revolution, something that the revolutionaries completely rejected and continued to demonstrate and protest daily for a year. Burhan was unable to form an executive government as the people continued to reject his rule. Burhan refused to hand over power and killed more than 300 young men and women demonstrators in the streets of Khartoum, Wad Madani and other cities in cold blood.

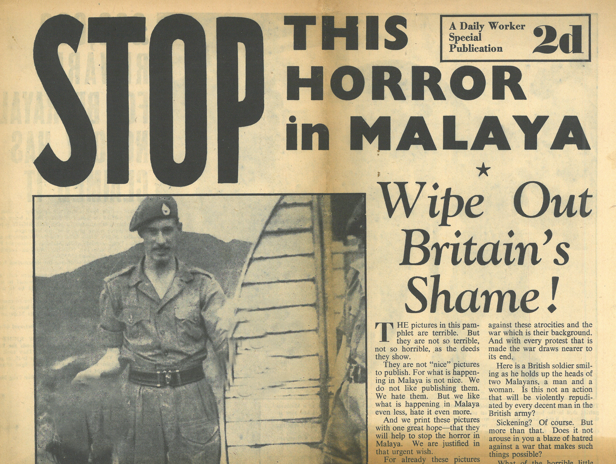

International complicity

Minister Abdullah Hamdok had passed a decision authorising the arrival of a special UN mission ‘UN Integrated Transition Support Mission in Sudan (UNITAMS)’. Led by a German expert, Volker Peretz, who had worked in Syria for years. From the early days, Mr Volker tried to play the role of mediator between the military and the revolutionary forces, with a clear bias towards the military, looking for a new partnership. The Sudanese reject his approach completely, but Volker and his international community have always worked against the will of the Sudanese people. Volker mobilised the AU, IGAD, Britain, America and Germany, forming a tripartite and quadripartite mechanism. The framework agreement sharply polarized the political actors and revolutionary forces, with some opportunists affiliated with the revolution supporting it and the radical revolutionary movement representatives in the resistance committees rejecting it.

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF), the Janjaweed militia, agreed to the framework agreement and Burhan refused to sign the security and military reform clause in which the RSF proposed to integrate its forces into the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) over a period of ten years. Military skirmishes began on the border with Central Africa and at Marawi Airport, until a war broke out on Saturday morning, 15 April (28th day of Ramadan), in the capital Khartoum. In the sports city, the airport, Omdurman and Khartoum.

The RSF broadcast a statement saying that it had taken control of the presidential palace, radio and television, leaving only a few parts of the General Command, after which it announced its complete victory and seized power, this time in the name of democracy and against Islamists.

The coup did not succeed and the Janjaweed suffered the biggest failure–they filled Khartoum with their armies and soldiers from everywhere, they took control of citizens’ homes, stole and looted them, expelled their families and barricaded themselves in them. The army bombed their camps, so they barricaded themselves in homes and hospitals, which Burhan also bombed without the slightest concern for the citizens. The war quickly spread throughout Sudan.

Hundreds of thousands were killed in Khartoum, Darfur and Gezira State. Nearly ten million Sudanese were displaced between displaced people in Sudan’s cities and villages and refugees outside the colonial borders.

In the war for gold and water, everyone is fighting by proxy

The United Arab Emirates is unabashedly supporting the RSF militia–financially, militarily, and through media. There are reports proving their funding of the militia, providing them with modern weapons and anti-aircraft weapons, building field hospitals in Darfur and Chad to treat the wounded and injured RSF mercenaries, in addition to supporting Haftar in Libya and the Russian Wagner forces. The UAE also mobilised its allies in the region, in Uganda, Kenya and Ethiopia, to put pressure on Burhan in order to pass their agenda.

On the other hand, the Islamists, who were ousted from power, found their way into the conflict, declaring their explicit and direct support for Burhan in his holy war, “the war of dignity”, against the militia, “the militia that came out of their womb”. Burhan found himself under their grip, heading to Turkey, the stronghold of the remnants of the former regime, and automatically directing himself to Al-Burhan, who a little while ago was crawling to normalise with Israel, has only the resistance camp with little support from the Ukrainian army, which officially said that it helped him come out of hiding and supported him with weapons in Khartoum and Darfur to limit the arrival of gold to Russia and the UAE.

In short, after two years and more, the war in Sudan has moved out of the logic of internal social conflict and turned into a global proxy war, led by the comprador in which the machines of global capitalism and its desire for expansionism and control over Sudan’s resources and geopolitical location. The imperialist expansionist proxy war against Sudan, its people, its revolution and its wealth.