Today, 15th May, Palestinians in Germany and everywhere commemorate the Nakba – “catastrophe” in Arabic – the massive expulsion and land seizure which took place in Palestine before and during the creation of the Israeli state.

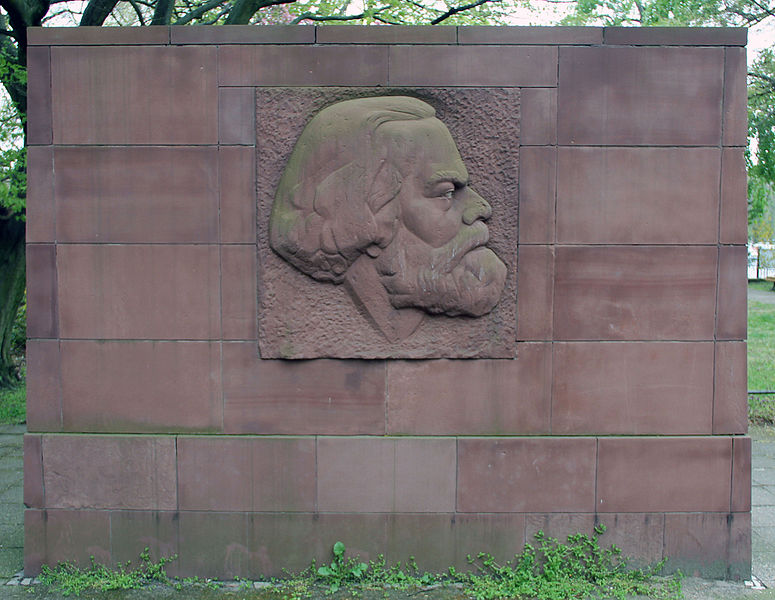

In Germany many shy away from an in-depth discussion about Israel-Palestine. But as socialists we have a responsibility to stand on the side of the oppressed – especially where it is difficult. Karl Marx once wrote that we must overthrow all conditions in which people are debased, downtrodden, forsaken, despicable beings. And who is debased today if not the Palestinian Jerusalemite families forced to demolish their own homes? Who is downtrodden if not the Palestinian workers who must stand for hours every morning at the Qalandia Checkpoint to be allowed a long day of hard work for a low wage? And who is forsaken if not the Palestinian refugees, who were prevented from returning home after the end of the war and are even driven through the world, stateless unto the third and fourth generation?

The real and current balance of power between Israelis and Palestinians could not be clearer, but this is rarely mentioned in public debate in Germany. This must urgently change. For this purpose, I would like to point to a few reasons why Palestine solidarity is currently so important from a socialist viewpoint.

Colonialism and the Dual Role of the Settler Movement

The Palestinian-Israeli lawyer and scholar Raef Zreik incisively articulated the dual perception of Jewish Israelis: “The Europeans see the back of the Jewish refugee fleeing for his life. The Palestinian sees the face of the settler colonialist taking over his land.”

This is often portrayed as a peculiarity, but this contradictory role of settlers is typical of a certain historical phenomenon: settler colonialism. This includes among others, with all their individual peculiarities and specificities, the United States, South Africa, and New Zealand. In these cases too, expulsion and oppression in Europe were central reasons why so many people became settlers: for example, the early British settlers in North America were persecuted because of their confession. Nonetheless, what followed in this, and in all these cases, was unspeakable horrific mass tragedies for the indigenous population.

The international legitimation of such states, including the State of Israel, is based on foreign domination and the right that great powers assume to rule the world and carve it up as they see fit. To this day, the State of Israel still celebrates and honours the Balfour Declaration of 1917 as a legitimation for its creation, in which the British colonial power proclaimed its support for the “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

The political and economic conditions which result from such constellations stand in sharp contrast to the democratic social order of solidarity which socialists want to build. Indigenous people are politically disenfranchised and oppressed, economically expropriated and exploited. The same is true in Palestine. The majority of those Palestinians who still live in their country are denied basic political rights. Meanwhile, the State of Israel continues promoting and legitimizing their displacement and land seizure, and the economic super-exploitation of the Palestinians continues to unfold in myriad forms.

A particularly stark example of the colonial-style super-exploitation can be seen in the industrial zones of West Bank settlements, such as Mishor Adumim, east of Jerusalem. Israeli businesses can cheaply produce here on land taken by force using super-cheap Palestinian labour, with workers paid far less than the Israeli minimum wage and enjoying no social rights. Although they are entitled to these rights, in practise no enforcement takes place. If workers rise up against such conditions, their boss can cause their entry permit to be revoked with a simple phone call, costing them their job. Few dare to jeopardise their livelihood in this way, and so the untrammelled super-exploitation goes on.

As socialists we know well how the precarious working conditions of many in this country threaten the wages and rights of all wage labourers. In the same way, the super-exploitation of Palestinians directly intensifies the exploitation of all workers in the Israeli economy, and indirectly weakens the position of the international working class through transnational competition. Socialists must not accept this! Colonialism must be torn down in every form – in Palestine and everywhere.

International Relations

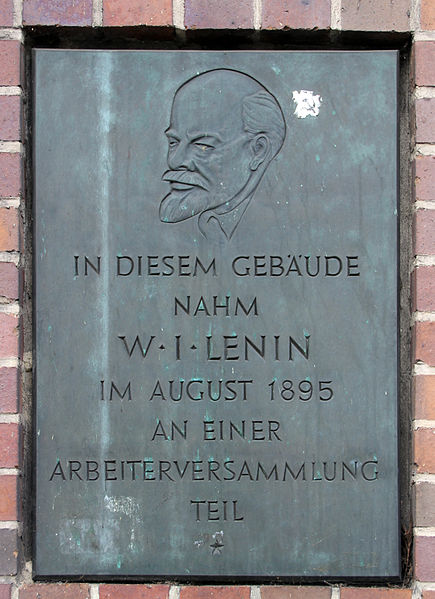

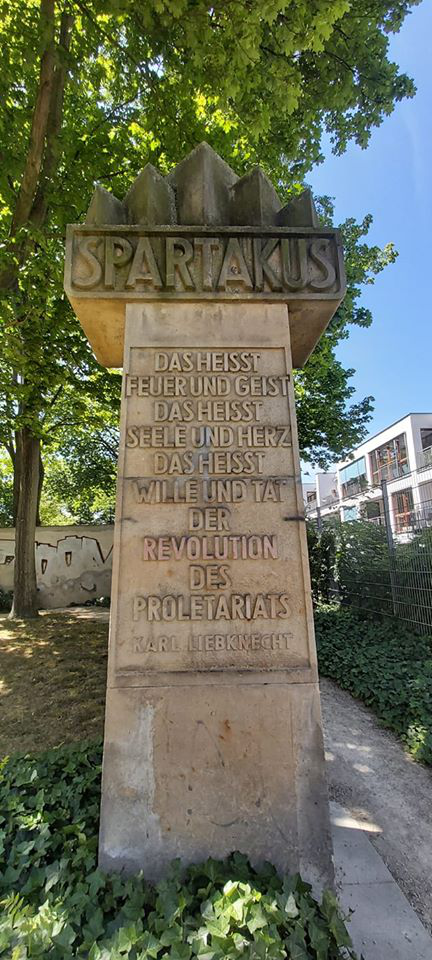

Yet to fight for a just world, we must concretely confront the international power structures which defend and entrench systematic injustice. Capitalism has long developed into a system of ruthless international power struggles – including the horror of war, for the global system of imperialism. Socialists like Rosa Luxemburg identified this over 100 years ago.

In this context, the State of Israel plays the role of a regional power under the patronage of global American hegemony. While the Israeli government can act with relative autonomy from Washington, at the same time it is dependent on its patron superpower – through massive military aid, and above all through diplomatic support and vetoes in the UN Security Council. Clearly, the two states find their vital interests fundamentally aligned. US politicians regularly speak of Israel’s supremacy in the region being a US interest. German politicians, like former Chancellor Angela Merkel, express a similar attitude when they proclaim that Israel’s safety is Germany’s Staatsräson (reason of state).

The imperialist world order allows such regional powers – even supports them, so long as they advance the interests of the great powers and their particular capital faction. At the same time, they do not tolerate any government or uprising which seriously calls these interests into question.

These power games are diametrically opposed to any emancipatory aspiration. For the Israeli government and their allies, the democratic revolution in 2012 in Egypt, for example, was a potential threat, while the arch-reactionary Saudi Arabia, which works closely with the US-American government, is treated as “moderate.” The Israeli government routinely stands on the side of the oppressor and against the people, not just in the Middle East, but also in South Africa, Latin America and South East Asia.

The Israeli ruling class, which oppresses the Palestinians, is thus thoroughly integrated with the ruling class of the Global North and networked with dictators worldwide. The fight against the one is a fight against the other. Struggles like the Palestinian fight for liberation and self-determination weaken imperialism and can strengthen revolutionary movements from below, far beyond the borders of the country in which the uprising takes place, and independent of the leading ideology of these struggles.

It is therefore no coincidence that just about all forces in the region and worldwide which stand against capitalism and imperialism support the Palestinian cause. Standing shoulder to shoulder with progressive forces in the region and in the world means showing and practising solidarity with Palestine.

German conditions

Despite everything, many Germans reject all arguments for Palestine solidarity out of hand. “This might work in other countries,” they will say, “but here in Germany we must stand with Israel.” This answer might prevent a significant amount of political flak, but it is not compatible with a left wing internationalism – nor even with the fight against oppression and nationalism in Germany itself.

The formula that the State of Israel stands for the Jewish people, and that Germany’s support for that State atones for the Nazis’ atrocities, has become part of the hegemonic self-perception of the German ruling class.

But this equation does not work out at all: most Jews of the world do not live in the State of Israel and do not vote for its government. And the mere thought that the oppression of another people can “compensate” for the unspeakable crimes of your own is a mockery of the victims of National Socialism. That said, we must also identify the political function this miserable formula plays in German society: legitimizing the existing arrangements of domination, both internally and externally.

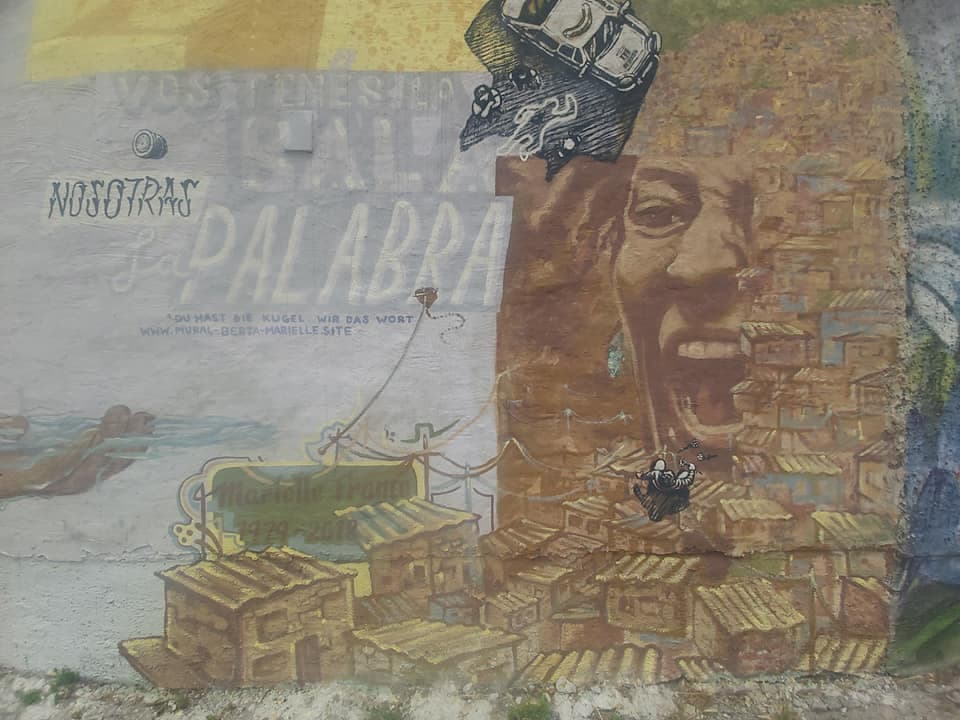

Internally, the formula of historical atonements establishes the basis for a new (ersatz) nationalism, which systematically culminates in the oppression of racialized migrant “Others”: in particular anti-Palestinian, but also anti-Muslim and even anti-Black racism – as could be seen in the cases of Nemi El-Hassan, the political purge in Deutsche Welle and the case of Achille Mbembe. Not even Jews, including Israelis, are safe from being openly delegitimised in the name of the pro-Israel line – as, for example, in the case of the School for Unlearning Zionism.

On the basis of this formula, the necessary confrontation with the fascist past and its afterlife today is displaced into new forms of exclusion and marginalisation. Instead of finally de-Nazifying its own security forces, Germany prefers to concentrate on “imported antisemitism”, which is used in particular to threaten (post-)migrants with exclusion from public life, or even from life in Germany altogether.

Externally meanwhile, this formula serves to legitimate Germany’s geopolitical ambitions. A “reformed” Germany can once more take economic and political “responsibility” worldwide. Its “Israel solidarity” serves as evidence that this is no cause for alarm. Without this formula, Germany’s massive rearmament would likely never have been met with the current outpouring of international support.

The anti-Palestinian positioning of the ruling class in Germany is a significant part of the framework of their legitimation and their geo-political aspirations. Palestine solidarity is therefore not merely a human and socialist responsibility, here as throughout the world – it is also indispensable for the concrete struggle in Germany.

“The Palestinian cause”, wrote the Palestinian revolutionary and author Ghassan Kanafani, “is not a cause for Palestinians only, but a cause for every revolutionary, wherever he is, as a cause of the exploited and oppressed masses in our era.”

This text first appeared in German in the SDS newspaper critica. Reproduced with permission. Translation: Phil Butland