In April 2020, a few months after the sea refuguee rescue organisation Mediterranea Berlin was born, one of our activists received a WhatsApp message from an unknown Libyan number. It was asking whether the “Ocean Viking” was close to Tripoli. The “Ocean Viking” belongs to another maritime refugee rescue organisation SOS Mediterranee. Our rescue boat is called “Mare Jonio” but was not at sea at that moment. The inexperienced activist had no clue how to answer this message, but knew they could not forward such sensitive information due to “aiding irregular migration” accusations.

Their immediate and rough answer read “It doesn’t work like that. We don’t have information, we don’t give information.” Yet, this made them feel guilty and powerless. There was a person in need asking for help, they felt compelled to do something. Thus, with further question, Mediterranea Berlin came to know the story of a 23 year old father who had sent the WhatsApp.

Salim Nyariga had left The Gambia and his unaware pregnant wife in January of the same year with one thing in mind:

“I was in school and I couldn’t stop worrying about the money for my wife and my future child. That Friday was the day I had this sudden idea: if all my friends have used this journey to help their family, why not me?”

At the beginning of the Corona crisis, even the human traffickers were afraid of the pandemic and would barely leave their homes. The departures from Libya were diminishing, the prices had increased and the weather conditions at the beginning of the year were even more discouraging. Crossing the Mediterranean had become more dangerous than ever.

At the time Salim sent the message he was waiting for his turn at the “connection point” in the Garabulli neighborhood, one of the places where people on the move wait for the moment to sail off. Many of his “brothers” met during his journey to Libya had already lost their lives trying to reach Europe. Salim’s greatest fear was not for his own life, but for the future of his newborn daughter that he saw for the first time on a photo sent by his wife while crossing the Tassili mountains in Algeria.

Salim wanted to go back home, but he was afraid to admit it. The 6000 km back to The Gambia would have meant he was defeated. Our activist encouraged him to follow his heart, there was nothing to be ashamed of. A repatriation through the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) was a concrete option. Salim felt relieved and after a year of waiting he caught one of the few available flights back to his home region where he could start over beside his family.

This particular happy ending was not what the activist was expecting on a first mission. Meanwhile, a year had gone by, in which Mediterranea Berlin had been taking to the streets shouting out loud “Refugees Are Welcome Here!”.

None of us will ever have the power to decide if, when and where to be born. It is the duty of the privileged ones to actively help whoever takes the first step to change their destiny. Whether going back home or in search of a new one, freedom of movement is a universal right. Crossing borders is the political act necessary to claim that right.

Mediterranea was born with the goal of helping people on the move, political actors claiming this right by crossing borders on land and at sea, in the Mediterranean as well as on the Balkan route and in Ukraine.

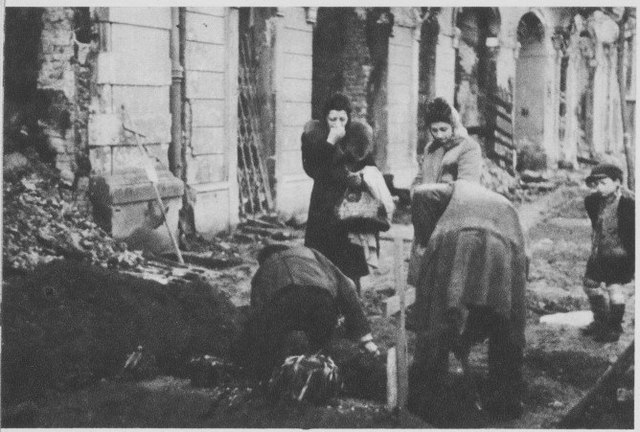

In the same spirit, we have been supporting the self organized movements born during the inspiring protests at the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) offices in Tripoli and Tunis. In the night between the first and second October 2021, the Libyan militias violently raided all houses in the Gargaresh neighborhood, arresting thousands of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. The ones who managed to escape had no other choice but to gather in front of the UNHCR headquarters, the UN agency supposed to protect them.

More than 4000 people started a movement, Refugees in Libya, asking to be recognized as human beings, the closure of all the detention centers financed by the EU and the evacuation towards safe countries. Instead of resorting to violence as a political means, they chose words. They opened a Twitter account through which they shed light on the Libyan black hole, thereby reaching international media and institutions, the African Union, the European Parliament, the Pope, human rights organizations and movements. They elected 2 representatives for each of the 11 national communities. Their assemblies would last for days on end practicing democracy and the values Europe keeps professing at home, while excluding the ones bearing the consequences of the colonial past and present.

The struggle of Refugees in Libya resisted for more than 100 days, until another brutal eviction by the militias resulted in a mass arrest and imprisonment of 600 people in the Ain Zara jail.

It was not the end though. On the contrary, the movement kept growing. Some made it to the other side of the Mediterranean and continued to fight alongside the European movements. The first joint initiative was organized in October 2022, on the occasion of the Italy – Libya Memorandum renewal where funds were promised in return that boats where stoped leaving Libya’s shores. Thousands of activists taking to the streets in 20 different cities.

As a result, 300 women and children were released from the Ain Zara detention camp. It was only the first step. The second was taken in December of that same year, in front of the UNHCR headquarters in Geneva. 50 more detainees were then freed. The last step brought the movement to Brussels in July 2023, at the center of European decision-making. The protest was directed towards the EU institutions responsible for the endless suffering and death at the European borders (EU-Council, EU-Commission and Parliament) as well as the UNHCR, IOM and Frontex (European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders) offices, involved in migration and refugee “management”. The remaining 250 prisoners were consequently released from Ain Zara.

All the detainees were finally freed. However, they are now in the same position as they were in more than one and a half years before. They are still in need of what they were demanding in front of the UNHCR headquarters in Tripoli in October 2021.

Libya is still not a safe place, but the battlefield of a civil war, ruled by warlords financed by Italy and EU. A hell for all the people on the move in search of a second chance.

The same goes for Tunisia, a land governed by a dictator who blamed the people on the move for his own economic failures. Kais Saied’s racist speech on the 21st of February 2023 incited and legitimized anti-black persecutions. Nonetheless, refugees in Tunisia risked their lives and reacted strongly, organizing protests in front of the UNHCR offices in Tunis where they appealed to the international and European institutions, asking to be evacuated. A desperate cry for help left unheard as shown a few months later. The EU – Tunisia Memorandum signed in July consolidated the dictator’s anti-migrant policies which escalated with the abandoning of almost 2000 people on the move in the desert at the Algerian and Libyan borders.

At the end of May 2023, the German Minister of Foreign Affairs, Annalena Baerbock, made a statement which was soon confirmed by the CEAS (Common European Asylum System) reform restricting freedom of movement: “Having no inner borders in Europe means that external borders must be protected”.

The message is clear, the EU is for the few. And yet the Ukrainian crisis proved otherwise. So we ask ourselves: are African wars less deadly than Russian ones?

The right to safety and pursuit of happiness belongs to every human being. This can be reached only through freedom of movement as a universal right. Until then, Mediterranea will continue to exist.

Read more about the work of Mediterranea Berlin.