In time for Peasant month, Friends of the Filipino People (FFPS) delegates, and allied organizations and individuals from several countries from around the globe took part in an international learning and solidarity mission (ISM) from October 11-15, in a concrete effort to extend the international community’s solidarity, learn from the Filipino masses their conditions and experiences, and amplify their call to expose and oppose the crimes of the US-backed Marcos administration.

ISM teams visited several regions emblematic of the issues faced by peasants and indigenous peoples in rural communities in the whole country who experience land-grabbing, displacement, destruction of livelihood in the name of private-and foreign-backed development projects. These communities are at the forefront of the struggle for the defense of the land and against climate imperialism in the Philippines.

Moreover, in these areas, there is clear evidence of a de-facto martial law in existence, where civilian rule has been overpowered by military rule. Farmers and community members are asked to log-in and log-out when going in and out to till their lands, and their belongings are checked. This is in line with the US-Marcos’ National Action Plan for Peace and Development (NAP-UPD) which in reality, aims to end all forms of struggle and dissent against feudalism, bureaucratic capitalism and imperialism.

Even the ISM teams were not spared. From day one, all ISM teams experienced continuous harassment, intimidation and surveillance by state forces. This clearly shows the US-Marcos regime’s attempts to thwart the documentation, which only further implicates the regime and its forces, underscoring that they have a lot to hide.

On the other hand, through the mission, international delegates saw the strength of the organized communities that are waging collective struggles against these injustices, and strengthened their resolve to broaden their solidarity to the Filipino people.

The ISM’s on-the-ground reports clearly highlight the justness of the different forms of struggles by the Filipino peasantry in the country. And as FFPS we strongly amplify the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP)’s and its allied organization’s position that real change and a just and lasting peace—a people’s peace—can only be brought about through the people’s democratic revolution that fights for national and social liberation.

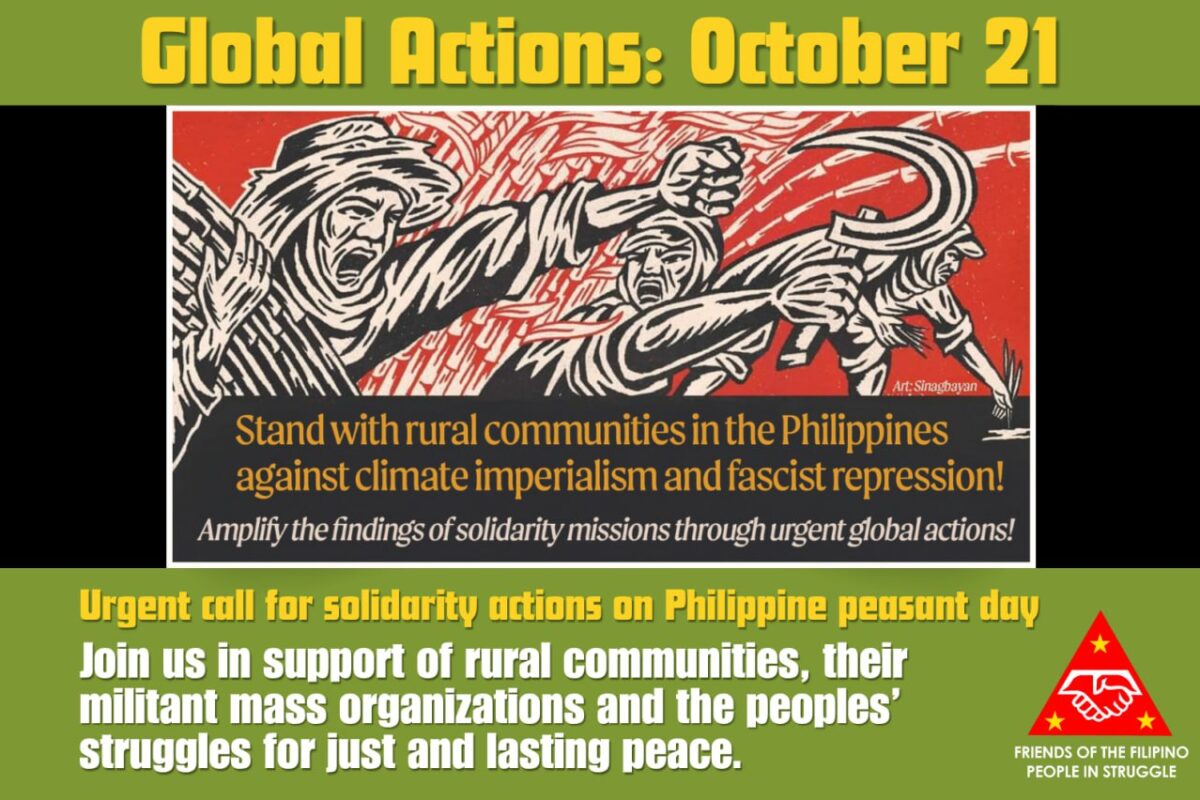

Call for global actions on October 21 – Peasant day in The Philippines

In this context, FFPS and other Philippine solidarity allies call on the international community to join in global action on the 21st of October, Peasant day in the Philippines, in support of rural communities in the Philippines, their militant mass organizations and the people’s struggles for just and lasting peace.

These solidarity actions will be important to help amplify the findings of the ISM, and the struggles and campaigns of peasants and indigenous peoples in the Philippines. At the same time these are urgent global actions to expose & oppose the US-backed Marcos regime and its crimes.

We encourage organizations and individuals, to at the very minimum, hold propaganda actions and employ other creative means to propagate and ensure media coverage of the situation and amplify the struggles of the Filipino people. For example, through graffiti actions, die-ins, street theatre, and others. At maximum, we would also encourage everyone to hold demonstrations and other protest actions in front of Philippine embassies and consulates in major cities across the world.

In the Philippines, Peasant day will be marked by huge mobilizations by the rural poor and their class allies. The peasants, farm workers and fisherfolk comprise the majority of the Filipino people. They cultivate the land and produce the majority of the country’s food. However, most do not own the land they till. They suffer the brunt of the violence under the semicolonial and semifeudal system. They face harsh economic repression through predatory land rent demands of landlords, usury, and other forms of feudal exploitation. The landlord class dominates all aspects of society in the countryside through reactionary violence.

Peasants, revolutionary backbone of the Philippine revolution

The dire situation drives many of the rural poor to resist and join the revolutionary armed struggle. As biggest class of Philippine society, the peasants and other rural poor are the primary force of the revolution being waged in the Philippines and of its protracted peoples’ war.

Amidst heavy state repression, the peasants organize resistance and build the people’s revolutionary mass organizations that advance their aspirations for genuine change, step by step. In FFPS’ webinar “Land is Life!” the Pambansang Katipunan ng mga Magsasaka (PKM) —revolutionary mass organizations of peasants—discussed and concretized the current situation and struggles of Filipino revolutionary peasants.

“Amid the onslaught of state terrorism, peasants in the mass base never wither and persistently look for the leadership of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), are eager to recover the affected chapters of the PKM, support the New People’s Army and recover and expand guerrilla fronts in the country.”

The PKM is not just a social club or cooperative, it is a revolutionary vehicle for transforming the countryside and mobilizing the largest class in the Philippine society for revolution. As mass organization, it is built step by step at the village, municipal, district and provincial levels, with the aim to unite the peasant masses to push forward the agrarian revolution and contribute to the wider Philippine peoples’ democratic revolution.

It is the dire conditions of the current system in the Philippines that provides the basis for why so many Filipinos take up arms in revolution. Internationalist efforts such as the ISM are critical for sharing experiences from the oppressed masses, and building solidarity for a sovereign Philippines. They highlight that the Filipino people have the right to fight back against the root problems of Philippine society, imperialism, feudalism and bureaucrat capitalism.

Join us this Peasant month October in supporting the peasantry—the primary force of the Philippine revolution! Join us in global action on the 21st of October! Amplify the findings of the ISM, support the struggles of rural communities in the Philippines and help expose the crimes of the US-Marcos regime!

Friends of the Filipino People in Struggle (FFPS) is a solidarity organization supporting the National Democratic people’s movement in the Philippines.