Hi Rasha, could you start just by introducing yourself?

Rasha (R-AJ): My name is Rasha Al-Jundi. I am Palestinian, who was born in Jordan but grew up in the UAE. I’m a second generation exile. My mother is from 1948 Palestine, my father is from a village outside Hebron.

I moved to Lebanon to study, and then worked in many different contexts as a humanitarian/development worker. But I recently decided to veer towards what I like to do, which is visual storytelling. I’m now appropriating multimedia stuff, including audio and archival images, in an attempt to find non-linear ways of telling stories.

I live in Nairobi, Kenya, but I shuttle between there and Germany because I have a German partner.

Today, we’re mainly talking about the multimedia project Cacti that combines photography with text and illustrations. What is the importance to you of the cactus?

R-AJ: Our relationship to the land goes far beyond the Israeli occupation which likes to greenwash and say that there were no trees and no people when Israel was formed – that it was a desert. The cacti and other trees in Palestine have always been there. We’ve traditionally used cacti to act as a natural fence around our houses.

Today they symbolize Palestine and its depopulated villages. If you google any current image of a depopulated village, you will find a lot of cacti growing there. They’re easy to grow, and they propagate very quickly. They can’t stop the tide.

And they’re the color of the Palestinian flag.

R-AJ: Of course, with their flowers. So the cactus is a very strong part of our culture. A lot of Palestinian artists also use cacti in their art, to symbolize Palestine or the forced expulsion.

There are a lot of walls in your photos, implying a comparison between the Berlin wall and the wall separating the West Bank from 1948 Palestine. What’s the significance of this?

R-AJ: The whole idea started when I met Michael. He told me that his family has been separated completely because of the wall. His father only found other family members when social media arrived. They didn’t know each other physically. Meeting someone in real life is also life-changing for me. Because I am a Palestinian but have never been there – I’m an exile.

Then we were talking about the Nakba ban last year, and reading about the silencing of Palestine, which is very systematic in Germany, especially over the last decade. It increased slowly and climaxed last year in Berlin.

I went away over Christmas and New Year last year, and contemplated what I’d read and heard, and decided to use the symbols that Berlin uses very well to commemorate its own history of separation, occupation, and colonialism on its own soil, to say that we are here.

I wanted to say to Germany that there is a shared history here, but you’re not seeing it. And I expect you to understand more than anybody else in Europe what is going on here, but you don’t. Instead, you use the Holocaust to explain your unlimited support to Israel. You don’t see that the wall represents occupation.

It is interesting that you’re talking about separation, because there is a very strong narrative in Germany that there was a terrible period of 40 years, where families were separated and people in the West and East were divided. This is rightly seen as something which was traumatic, and yet there is no comprehension that this has been going on for Palestinians for even longer.

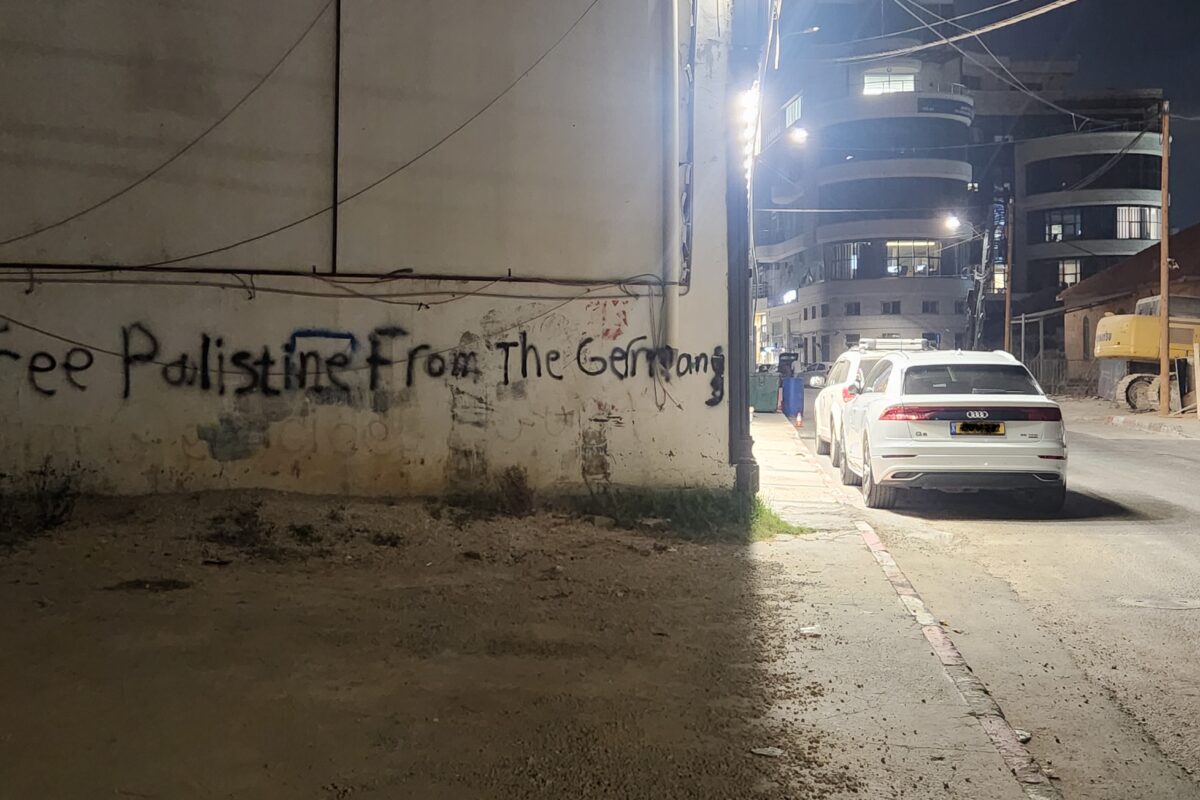

R-AJ: Exactly. Let me tell a small anecdote. A friend’s parents visited her here in Berlin, and when they saw the wall they were laughing at its size. They said “this is a child of our wall”.

Michael told me how offended he felt when he went to one of the monuments just across from Checkpoint Charlie. There is a sign in three different languages saying “imagine a wall separating you”. But this is what Palestinians still experience every day. You don’t have to imagine it in history – it’s happening in Palestine. Yet Germany blindly supports Israel, not even recognizing the illegal settlements.

Berlin is a very interesting city. They do a very good job in commemorating historical events, whether it’s the wall, or the Holocaust, or other things that this city has witnessed and experienced. It was flattened in the Second World War. It’s very well documented, whether in museums or in outdoor spaces. I find that really good for visitors to understand where they are.

I just wanted to ask, when will we get the chance to commemorate our dead and our history?

Let’s talk about the Holocaust. There’s a photo in your exhibition of people going through the Holocaust Memorial wearing keffiyehs. When I saw the photo, I thought two things. Firstly, how moving it is. Secondly, that it will provoke a backlash.

R-AJ: It provoked a reaction – both positive and negative. The positive ones all came from people who oppose the instrumentalization of the Holocaust because they have family members who were killed in the Holocaust in different parts of Europe. They think that their history is being employed now to suppress Palestinian voices and to support oppression and colonization.

The negative comments were that it’s insensitive to use the Holocaust memorial site. A very basic and shallow argument. My intention was to provoke a debate. I view a lot of flat and boring artworks out there all the time. I didn’t want to be part of that.

Given the level of industrial genocide involved in the Holocaust, do you think it’s legitimate to compare what’s happened to the Palestinians to the Holocaust?

R-AJ: I don’t know if I was comparing as much as I was drawing joint histories of forced dehumanization. Germans fail to link their history of colonization of Africa to the Holocaust. This dehumanization of people didn’t stop or start with the Holocaust, which is what they fail to see.

We Palestinians are being dehumanized by a colonial power, supported by other colonial powers. I show the shared history rather than compare what is happening on the ground. On the other hand, Ilan Pappé recently said that Palestinians are facing an incremental genocide.

Fortunately, the world did not agree with the Holocaust. But unfortunately, they’re not seeing that the Palestinians are facing this on a daily basis. Just last night, we lost 13 people in Gaza. Every day there are two guys here, five people here in the West Bank. I feel like the world either needs a big bomb or a big concentration camp to draw its attention or it doesn’t see anything.

There is a call for action here. You cannot just say we don’t accept the Holocaust, because it was so industrial and huge – which it was – but we accept what’s still going on with the Palestinians.

As someone who has spent most of your time outside Germany, how visible have the German Nakba and demonstration bans been from the outside?

R-AJ: It’s very visible. Even before coming to Berlin last November, I already read about it. It was all over the international news and mainstream media. In one of the images in the project, we actually have two tourists posing with us. They’re from Greece, they live in the UK, and they wanted to join. They had read about the ban, and said they think it is very unjust.

My brother who lives in the UK, another brother and sister in Canada, they all heard about it. And they were all asking me what’s going on. People in Jordan asked me if I would be put in jail for wearing the keffiyeh.

Is the discussion of Palestine different in Germany?

R-AJ: Many Germans choose to keep their heads in the sand. We’re talking about educated urban people, not some village in Bavaria. A majority of people who I speak to, who say “it’s really not my fight”, or “I’m so sorry, this is happening”, as if I tripped and fell on my leg.

I don’t find a lot of people who are keen on learning and reading and asking “what can I do about this?” We do have a German photographer ally, who’s helping us print the images at a discounted rate, and there are a lot of German activists who are supporters of our struggle. But the majority just wants to put their heads in the sand and say: “look, it’s too complicated”.

Even if you explain everything very slowly and give context, they still lack understanding (or choose not to understand perhaps). It’s the Holocaust education and the guilt. They see the Holocaust as an isolated case, and just a German thing. The guilt is either bottled up or comes out in completely different and really weird ways.

Have you sensed any change in the 12 years you’ve been in contact with Germany?

R-AJ: I estimate that it’s pretty much the same. From my side, the change has been in me because I’ve got more involved with Germany rather than just working as an activist in the Middle East within my comfort zone.

This apolitical thing about Germans really irks me. They choose issues like climate change or Ukraine which are “neutral”. They choose feminist issues around Iran – forcing women to wear the headscarf but not India where women face oppression and aggression every day because they’re Muslim. They’re picking and choosing the things which agree with their Western mindset.

Michael has just joined us. Could you say who you are?

Michael Jabareen (MJ): I am just a Palestinian. Someone who lived in Palestine for 27 years before coming to Germany. I’ve been involved in the field of art and design, starting with art activism in Palestine. I’ve become involved with intersectional struggles.

Our side is having some small victories. I’ve come to this interview from the court case of a Palestinian artist who was arrested on Nakba Day last year, but the judge ruled that she does not have to pay her fine. Resistance is having an effect.

MJ: From what I saw from the court cases, it was very clear from police testimonies that the police officers themselves had no clear idea of what exactly is banned. Whenever the judge or the lawyer asks the police witness about the exact order that they got, they simply say that we just had an order to check if there is any Palestinian gathering, and to stop it.

When they were asked about how they would identify people who are gathered for a Palestinian assembly, they say that just wearing a scarf or anything related to the Nakba is enough. And of course, there were a lot of people who got arrested without having these symbols. It was very clear that people were kettled and arrested based on racial profiling.

It’s not a good look for a German policeman to say in court: “I didn’t know what was happening. I was just obeying orders.”

R-AJ: There’s also this movement since Documenta last year. There is this way of looking at the arts and trying to scrutinize how art is being used for political reasons. It’s very draconian. There are a lot of judgements and pre-judgements sometimes in Germany without even looking at the content.

Do you have any last words?

MJ: I had a conversation with one of the policemen who was taking people to the police cars. I was saying that people are being arrested for doing nothing wrong. You are arresting people just for being Palestinian and presenting themselves visually. And one of the policemen said: “I know that arresting people is wrong, but these are the orders”. It is not that different from the past, just putting it under the cover of so-called democracy.

Tomorrow’s demonstration by Nakba75 has been banned by the Berlin police. A full programme is still taking place near Köpenicker Straße 40. Full details here.. The rally of the Jüdische Stimme has not been banned (yet). Please come to Oranienplatz at 3pm on Saturday, 20th May to show that you will not accept such repression.

Gallery – Cacti: A Visual Protest Against the Silencing of Palestinian Voices in Germany