Hello, thanks for talking to us. Could you start by introducing yourself? Who are you and how are you active?

Thank you for this chance to elaborate on the situation in Sudan. I am Shadia Abdel-Moneim, the political secretary of the communist party branch in Germany, a human rights defender, especially vulnerable groups. I am one of the founders of a number of associations and initiatives [established] as resistance bodies to the Bashir regime throughout the 30 years of the bloody dictatorial Islamic regime in Sudan. I worked closely with a number of women’s and youth groups in conflict areas for peace and justice.

Today, after the revolution, I am struggling with groups of Sudanese activists inside Sudan and in diaspora in order to achieve the slogans of the revolution and establish a better reality for Sudanese people.

Briefly, what is happening in Sudan at the moment?

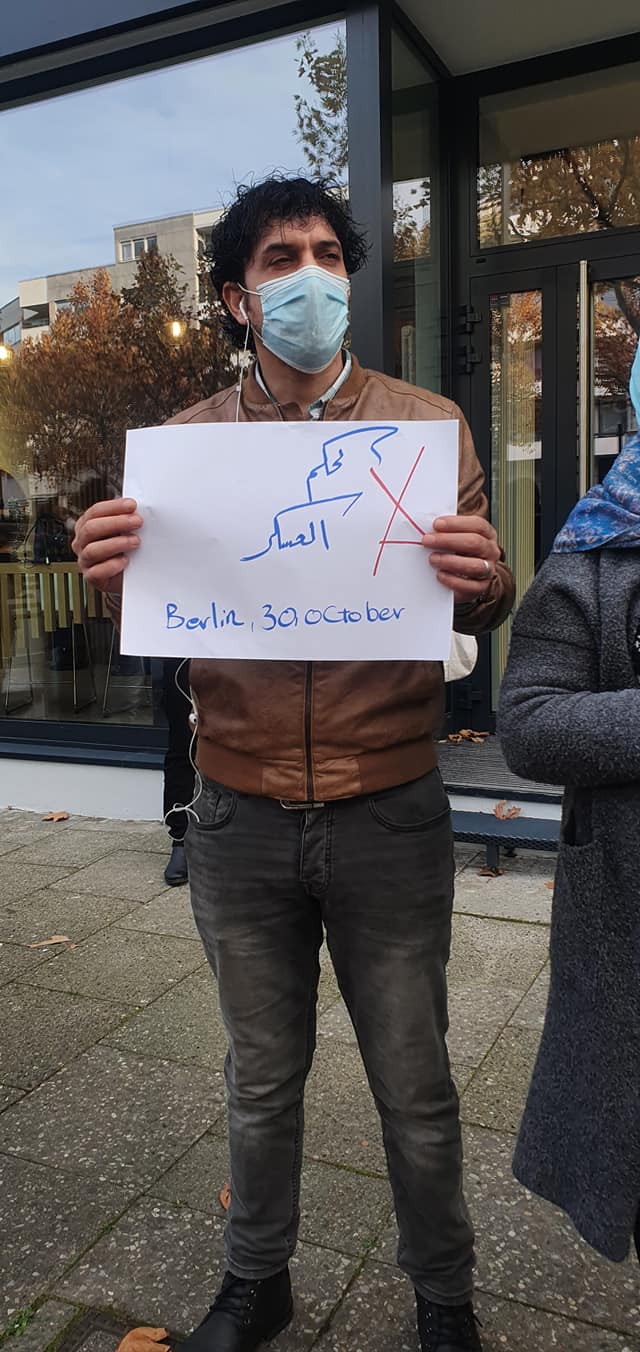

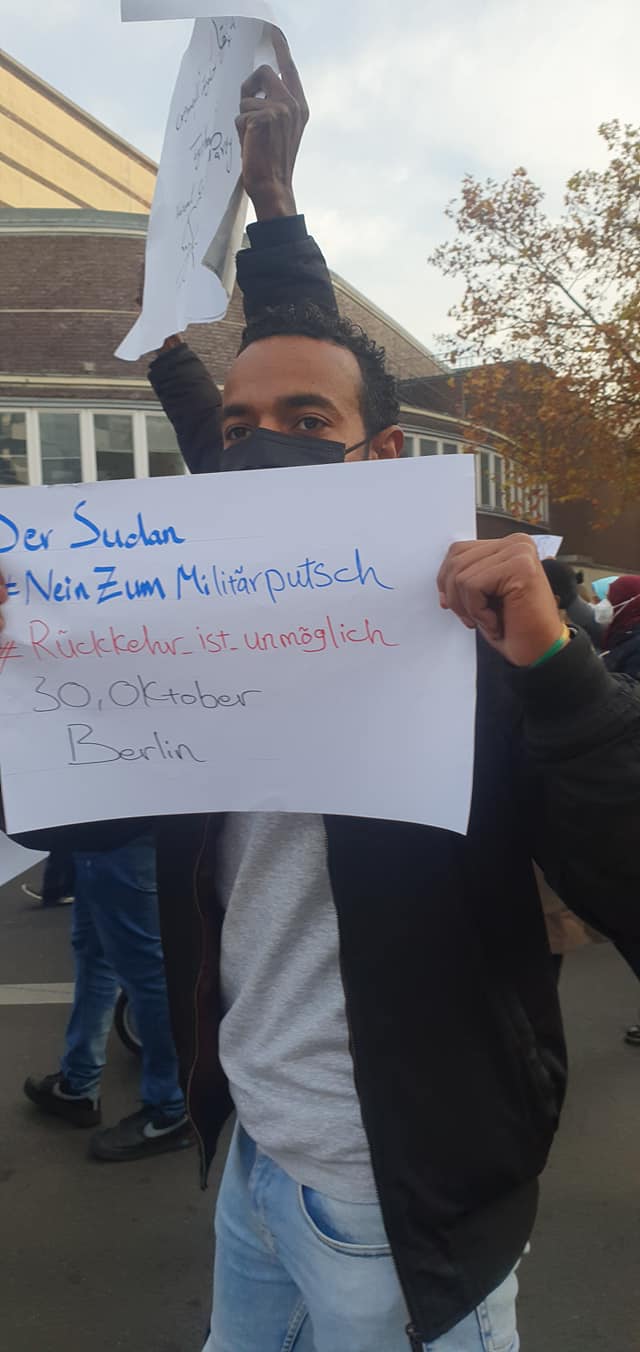

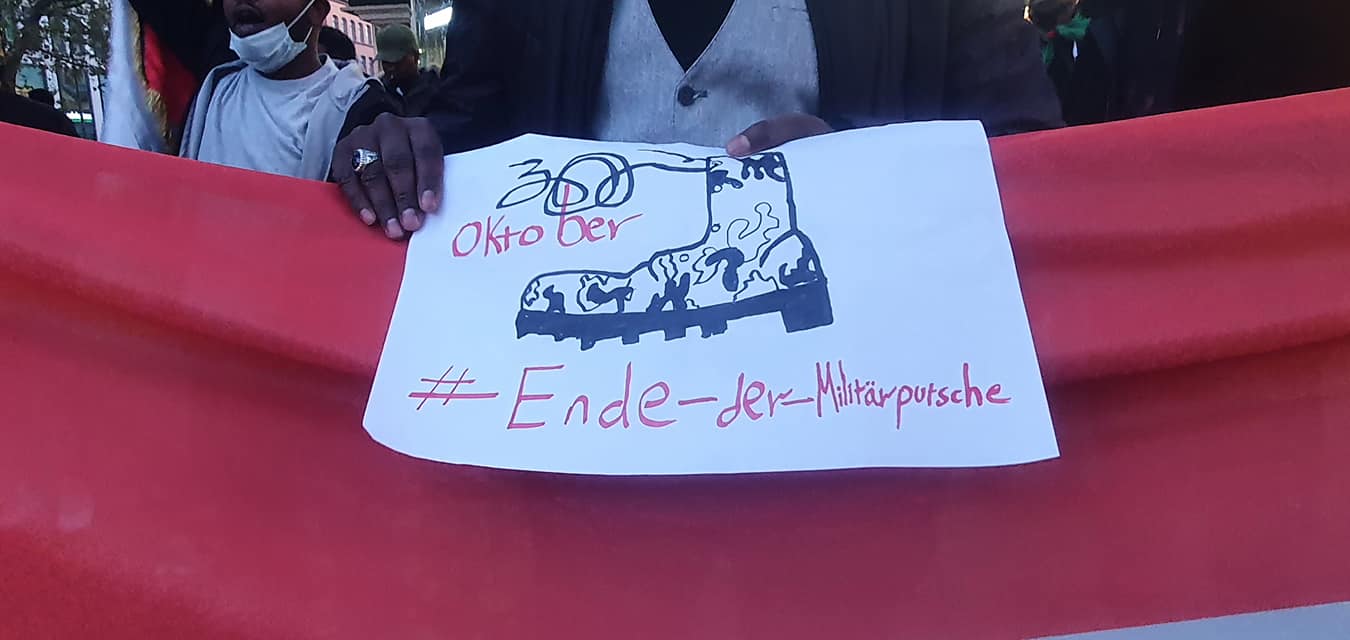

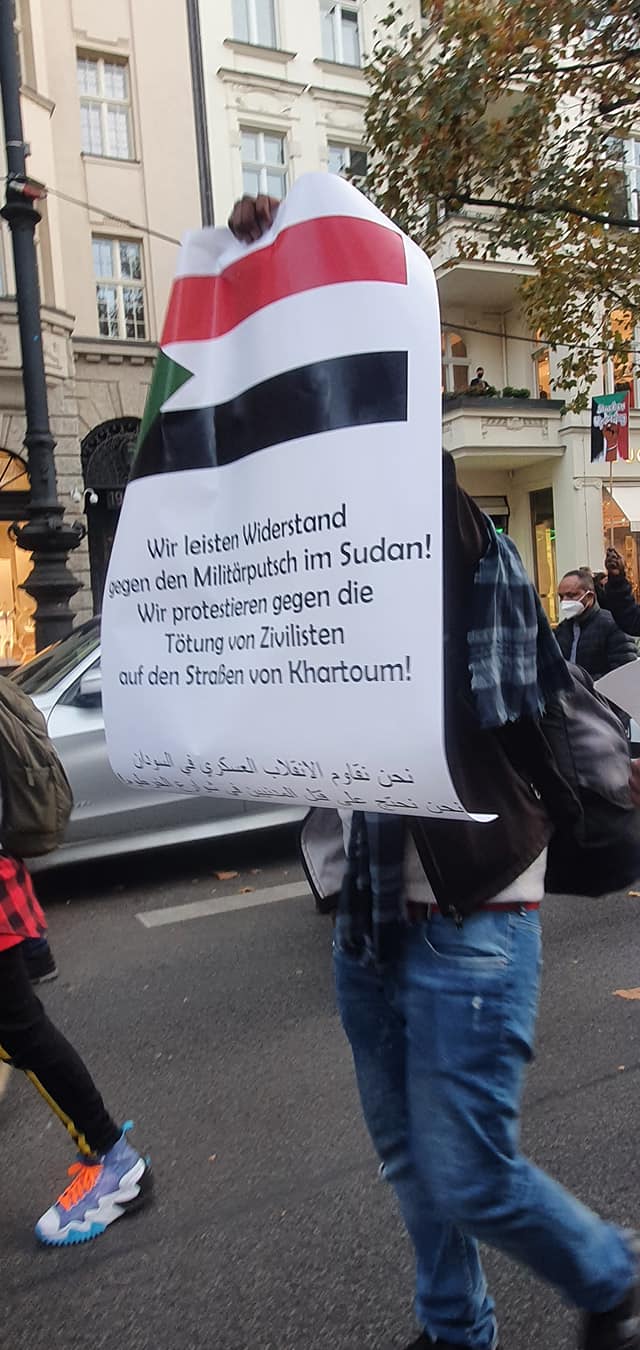

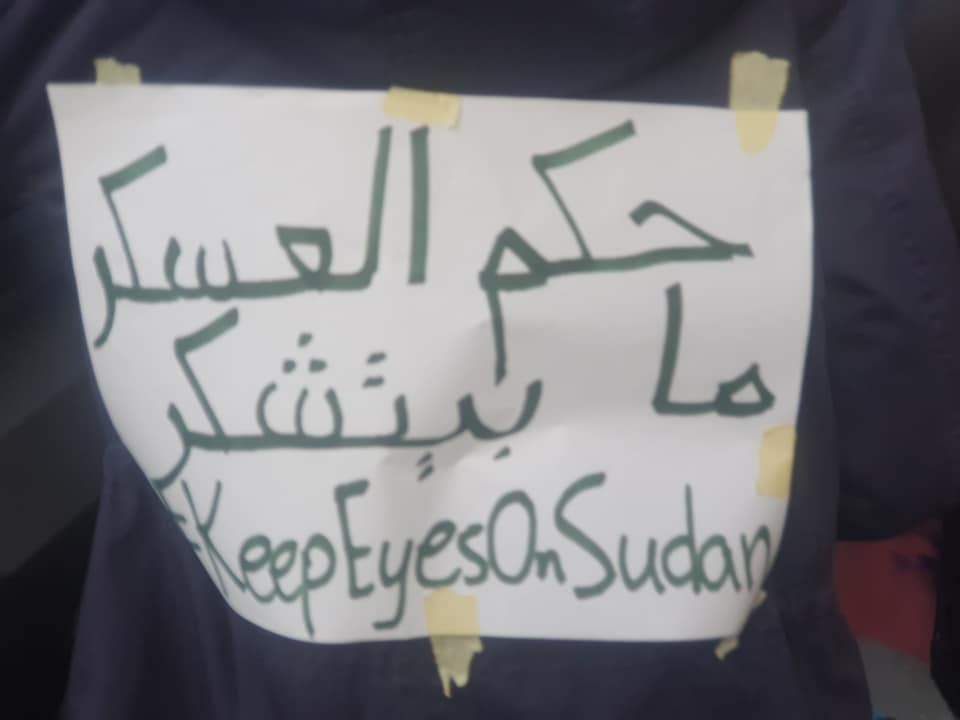

The security committee of the Bashir régime, which shares the transitional government with civilians, led by its chairman Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, carried out a military coup on October 25, 2021. This was part of a series of military coups which began with the palace coup of April 11, 2019. The goal is the same – to prevent the mass movement from achieving the goals and slogans of the glorious December Revolution.

Who is Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and should we fear him?

Burhan studied in a Sudanese army college, then later in Jordan and at the Egyptian military academy in Cairo, where fellow alumni included Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. Burhan and Sisi are longstanding friends, though the Sudanese general has lifelong affiliations with the kinds of Islamist movements that Sisi has outlawed.

He was absolutely instrumental to the devastation caused in Darfur, he fought in the region and was a military intelligence colonel coordinating army and militia attacks against civilians in West Darfur state from 2003 to 2005.

Burhan’s time in Darfur is significant also because it brought him into contact with the warlord Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, widely known as Hemeti. Hemeti became leader of the Janjaweed, the Arab militias that brought death and despair to Darfur, and which have since morphed into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), with Hemeti still at the helm.

These various sources of power and wealth have come under threat from Sudan’s civilian-led government and it is thought that this is partly why Burhan and Hemeti have moved when they have. Both he and Hemeti are said to be mindful of being held accountable for past actions in Darfur, and Burhan had been lobbying to dissolve the civilian-led council of ministers.

This is Burhan and Hemeti’s coup, but the relationship between the two men is difficult because, among other things, Hemeti projects himself as a leader abroad, and is closer to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Abu Dhabi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed. Burhan is considered to be Egypt’s man. Hemeti is a more charismatic, more cartoonish figure than the quietly spoken, methodical Burhan, and the RSF leader is more closely associated with the atrocities surrounding the transition to democracy – most notably, the massacre of more than 128 people in Khartoum in June 2019 – than the armed forces general.

Two years ago, mass demonstrations removed former President Bashir. Are those forces still active, and how are they reacting to the coup?

Protests and resistance against the Bashir regime began in Sudan from the first day of his rule, and the regime met it with brutal repression. Trade unions and professional and factional unions were dismantled. The regime also worked to weaken and divide political parties.

In 2008, journalists began to form the Journalists’ Network. After that, the Doctors Committee and the Democratic Lawyers Alliance were formed, and the features of this alternative gathering of the unions seized by Al-Bashir’s authority began to become clear. At the initiative of the Journalists’ Network, a grouping of these three bodies was formed, and the Teachers’ Committee joined it until the assembly became composed of 17 unofficial union bodies.

These bodies demanded rejecting partnership with the military, rejecting the flawed constitutional document, rejecting the incomplete Juba peace and adhering to a transitional period led by civilians. Thus, we can say that the masses that overthrew Bashir are able to thwart the coup and adhere to the goals of the revolution, and are now more organized to do so.

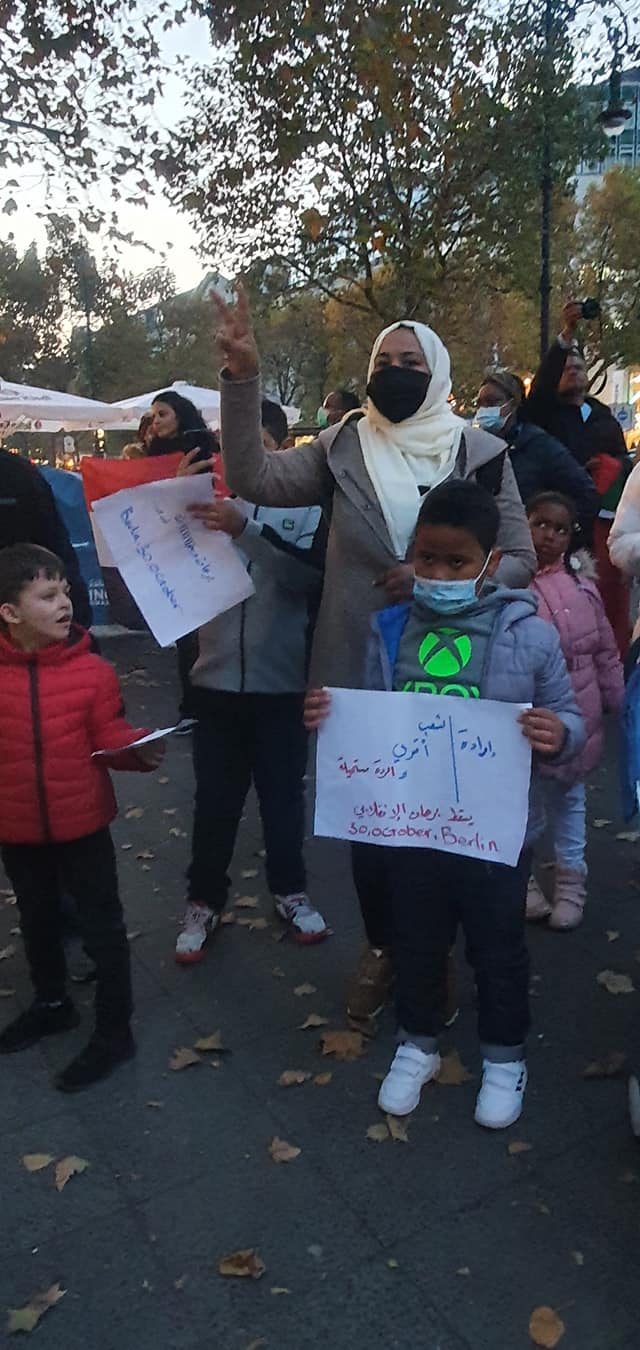

What is the role of women in your revolution?

It is well known that Al-Bashir’s was a hardline Islamic regime, that worked in coordination with international Islamist groups, which pursued an approach hostile to women’s liberation.

Since its early days in Sudan, Al-Bashir’s regime began to restrict women and imposed on them the so-called Islamic dress, which is a headscarf and a black abaya. Women resisted in all their factions, except for those belonging to the ruling organization. The regime retreated under the weight of women’s resistance and was satisfied with the veil, and women’s resistance continued.

In the early nineties, the regime enacted what is known as the Public Order Law, which blatantly targeted women. It also enacted articles in the criminal law that criminalize women. Through its arsenal of laws and restrictions imposed on women, the regime has been confiscating the gains that women gained through hard struggle since the fifties of the last century.

In response to all these attacks on women’s gains, women organized to create resistance bodies from pressure groups and associations under different names, but all of them came together to resist the regime and its degrading laws against women.

I can say that women determined their position early on from the regime, and the unity of purpose helped them in this, and the resistance of women continued until the revolution, and they were among the most important factions that led the revolution, and this was because they were organized and ready to topple the regime more than others

What is the state of the organised Left? What parties are there and how are they relating to the movement?

The largest left-wing parties in terms of organization, number and political position is the Sudanese Communist Party. Other leftist trends include Baathist and Nasserist parties influenced by the Arab National socialism.

With the exception of the Communist Party and the Sudanese Socialist Democratic Party, all of these parties supported the neoliberal Hamdok government and now stand against the will of the people to break up the partnership with the military and proceed with building a civil and democratic state.

What have you learned from uprising in neighbouring countries like Egypt?

Despite the geographical location of Sudan, the nature of Sudanese political and personal life itself is different, and therefore the experience of the revolution in Sudan is different. Since political independence, the Sudanese have struggled for freedom and democracy and carried out two revolutions, October 1969 and April 1985. The two revolutions were aborted with regional and international interventions.

In both revolutions, there was a political leadership that, despite its weakness, was present and in one way or another related to the masses. This was not the case in the Egyptian revolution, where the leadership of the revolution was activists. In Sudan in recent years, voices have risen asking the masses to isolate and bypass parties, and these voices are trying to implement the Egyptian model in Sudan.

In my estimation, the most important lesson that we have to learn from the revolutions of the Arab Spring, and specifically the Egyptian revolution, is to keep the army away from practicing politics, prevent the army from sharing power and prevent their control of any economic investments. We should be strengthening the political leadership represented in political parties, trade unions, and resistance committees.

Do you think that the US and German governments can play a positive role in your liberation?

Of course, it is clear that international and regional foreign interventions in Sudanese affairs have had a very negative impact on political stability in Sudan since political independence in the fifties. In my personal assessment, Germany is trying to understand the nature of Sudanese society, political and social, and this is a correct start. Germany and the United States of America can help the Sudanese to build a state of freedom, peace and justice, the civil and democratic state for which they gave thousands of martyrs.

This can be done first: by hearing the voice of the masses represented by its living forces from resistance committees, political parties, factional and demanding forces.

Second: Stop supporting the militias, as the European Union, led by Germany, used to do, when they supported the Janjaweed militias led by Hemeti in what is known as the Khartoum process to stop illegal immigration and extend the borders. In return, they have to help the Sudanese in disarmament, demobilization and reintegration of these various militias in accordance with international principles, and help in building a single national army that performs its globally recognized mission of protecting the homeland and guarding the constitution.

Third: restricting the hand of the regional axes from interfering in the internal affairs of the Sudanese state and respecting the right of the Sudanese to formulate the future of their state and national sovereignty by applying pressure on them instead of pressure on the Sudanese to accept fragile and harmful settlements for the future of the revolution and the state

Fourth: Not to pressure the Sudanese, represented by the political parties and the civilian component, to accept partnership with the military, to return to the constitutional document rejected by the masses, or to abide by the Juba Peace Agreement. It did not address the roots of the peace crisis and did not accommodate all conflicted parties, such as those displaced by the war and the factions of Abdul Wahed Muhammad Nour and Al Helou.

They can assist the Sudanese in dismantling the institutions of the former regime by freezing the assets of its symbols abroad, pressure to hand over wanted persons to the criminal court, and technical assistance in handing over companies and funds in the possession of the military to be under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Finance.

Technical assistance in building the institutions of democratic transition, such as the establishment of the Constitutional Court, the reform of the judiciary, the establishment of the constitutional conference, the establishment of the Electoral Commission, the enactment of the election law, and the restructuring of the Ministry of Statistics in preparation for the population census.

In my estimation, this is the role that helps in the stability of Sudan. Other than that, if settlements are imposed, protests and political turmoil in Sudan will continue.

What happens next?

The coup is isolated internally and externally. Also knows that the international community, the African Union and the axes do not dare to support the coup in light of the unequivocal popular rejection.

There are compromises and mediation efforts taking place now, but it is also very clear that no one is negotiating with the masses and no one is negotiating in the name of the masses. Which means that any solution will not work if it does not take into account the demands of the masses that raised them in their slogans.

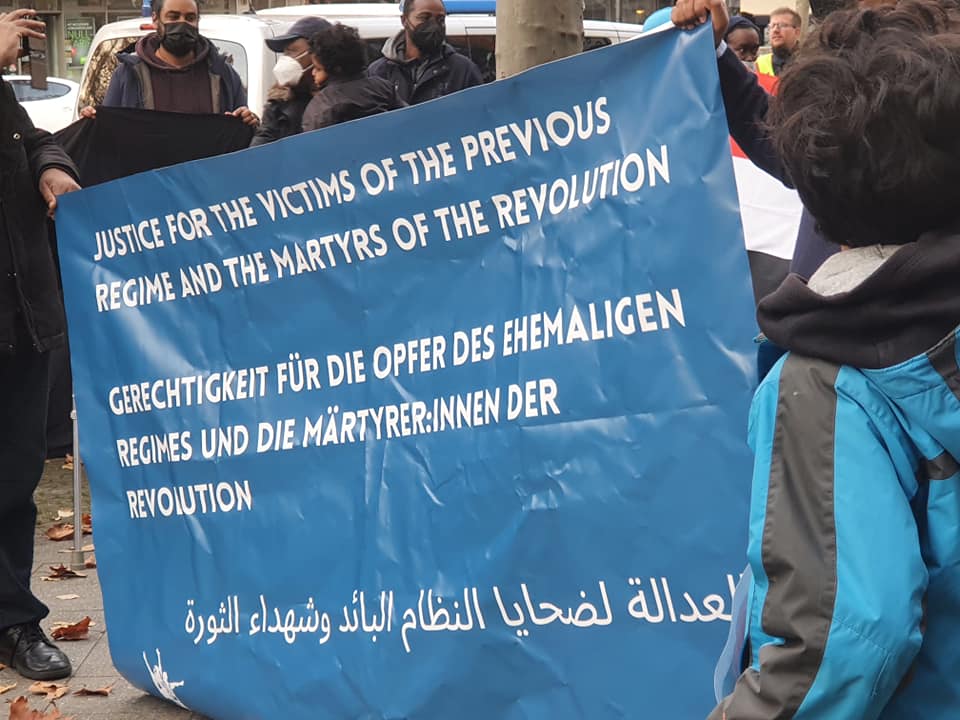

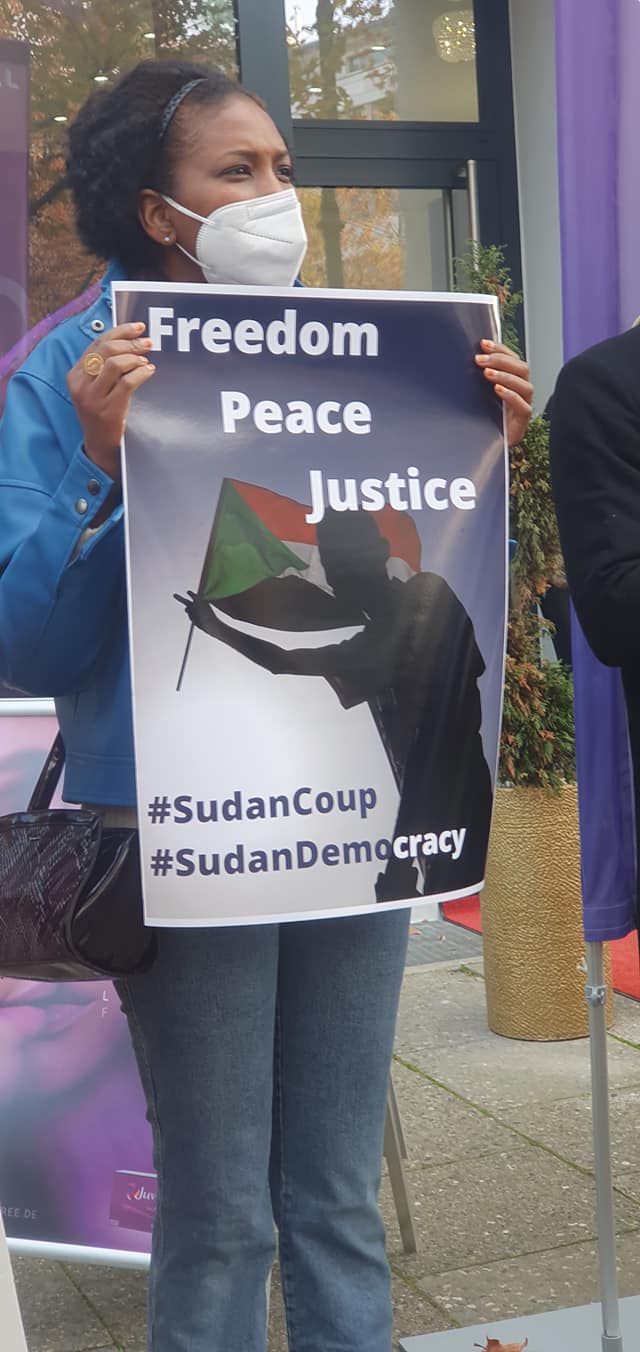

The December 2019 revolution was the result of the accumulation of a continuous struggle over the years. The peaceful resistance will continue using the same tools from peaceful protests to civil disobedience and political strikes, until the Sudanese reach the slogans of the revolution: “freedom, peace and justice, civility, the people’s choice”.

No matter how many obstacles are placed in front of them and no matter how long it takes, I know exactly how strong the Sudanese are and the strength of their patience whenever they have a clear, agreed goal.

How can people in Berlin support your movement?

I am absolutely certain that international solidarity and belief in the right of peoples to freedom, peace, justice and a decent life will help a lot in changing the balance of power and help public opinion to put pressure on their governments in choosing to align themselves with the will of the people.

People in Berlin can:

- Organise solidarity activities with the Sudanese people.

- Lead a global campaign to put pressure on Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to restore the internet and communications.

- Organize a large campaign to stop the killing and arrest of protesters.

- Put pressure to hand over wanted persons to the International Court

- Call on the international community to declare the Janjaweed a terrorist organization.