Whenever I return to Berlin from any long absence, I feel compelled to go to the Neue Wache on ‘Unter Den Linden’, to pay my own small homage to a great artist. There is an enlarged version of Käthe Kollwitz’s original ‘Pieta’ cast in 1937. A mother holds her dead son, while following Michaelangelo, it remained entirely her own.

She was a worker’s artist. Her central theme largely became the pointlessness of war, the intense grief of the parents of the fallen soldiers. This theme became ever-larger following the death of her first son, Peter, in World War 1 – only ten days after he volunteered for the front. After the late 1920s this theme became intense and generalized to the ever present ‘Death’ that stalks the working class.

What sort of an artist was she? I believe she transcends ordinary labels and is not simply a ‘socialist realist’. Because her personalisation of ‘Death’ approximates to Symbolism, and she – as she admitted herself – dwells on the dark side of life. Her meditations such as on ‘the Peasant Wars’ mark her as a socialist realist. A complexity then, reflecting life’s mottled and contradictory nature.

I was newly struck by the theme of ‘death’ when I recently visited the new Kollwitz Gallery. This collection was previously in an old house near Savignyplatz, but has moved to Schloss Charlottenburg, perhaps an incongruous site for this great artist. However, she deserves the enlarged space it will ultimately allow, many works in the catalogue were not shown before. (‘Kathe Kollwitz”, Zeichnung, Grafik, Plastik”; Martin Fritsch; E.A. Seemann Leipzig 1999). But this new venue also reflects an increasing respect. Previously her work was perhaps side-lined as too “committed” in the West, and too redolent of the GDR where she was an honoured artist.

The works currently at Charlottenburg are mainly etchings (scratches on a metal plate covered with a wax-like ‘ground’ exposes metal; which being placed into acid become corroded and deeper, allowing them to hold ink); and lithographs (where a special pencil draws a design on a plate which holds onto ink for a print). Although the famous “Turm die Muetter” 1937 bronze of a famous lithograph is also there. Further rooms are in preparation for the vast holdings.

Undoubtedly Kollwitz identified with the worker’s movement. Her father, Karl Schmidt, actively supported the defeated revolution of 1848. Karl Schmidt never gave up his socialist views, and having supported the 1848 revolution he could not practice law, and became a stone-mason. Her mother was a socialist. A family favorite reading was Freiligrath’s German translation of Thomas Hood‘s poem “The Song of the Shirt.”

Her brother, Konrad, became an active member of the Communist Party Germany (KPD). She married Konrad’s socialist friend, Karl Kollwitz – then a medical student. Karl set up practice in a (then) working class Berlin district of Prenzlauer Berg.

As a child she admired etchings by William Hogarth. Young Käthe drew pictures of the Polish dock-workers in the harbour. Her father got her to The Berlin Academy of Art, the Women’s School in 1884. By 1893, she drew lines with an almost infinite degree of shading from black to white. Later under Ernst Barlach’s influence, she started wood-cuts, achieving stark clarity. Still later she began sculpture. Such were the forms she mastered. But she had long ago found her content – working people. This never changed.

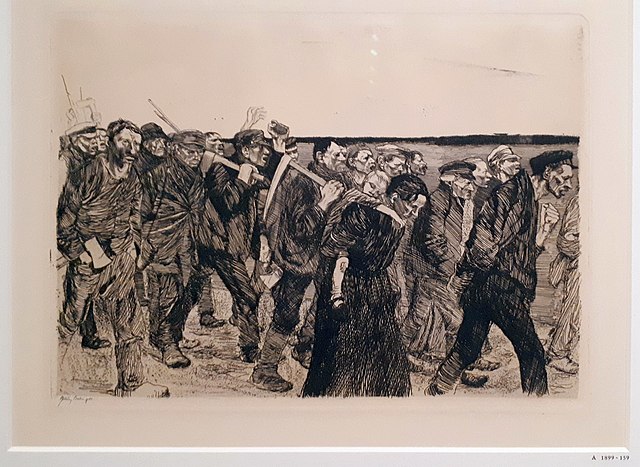

By 1897 she translated Gerhart Hauptmann’s play ‘The Weavers’ into a visual drama of six scenes, depicting the 1844 rising against mill-owners. These led the famous painter Adolph Menzel to nominate her for a Gold Medal at the 1889 Berlin Art Exhibition. She was denied this by Kaiser Wilhelm II because of the class content of her work. In 1901-1908 she created 7 etchings of Wilhelm Zimmermann’s “Allgemeine Geschichte des grossen Bauernkrieges”‚ The Peasant Wars. These are on display in the Charlottenburg gallery currently.

By 1919 she was made a member of the Prussian academy of Arts and became the first female professor of Art in Germany.

In her married life, she saw the working class day and night – at their most vulnerable, while they confided in Karl as patients. In all this, she saw beauty in workers. Her aesthetic was different from that of the bourgeoisie:

“But my real motive for choosing my subjects almost exclusively from the life of the workers was that only such subjects gave me in a simple & unqualified way what I felt to be beautiful. For me the Koenigsberg longshoremen had beauty… the broad freedom of movement in the gestures of the common people had beauty. Middle class people had no appeal for me at all. Bourgeois life as a whole seemed to me pedantic… I have never been able to see beauty in the upper class educated person; he’s superficial; he’s not natural or true; he’s not honest, and he’s not human being in every sense of the word.”

“Käthe Kollwitz; „Tagebuchblatter und Briefe [Diary & Letters]”; Ed Hans Kollwitz; Berlin; 1948; p. 43.

But she never considered herself a politically committed “communist”. By 1921 she was writing:

“In the meantime I have been through a revolution, and I am convinced that I am no revolutionist. My childhood dream of dying on the barricades will hardly be fulfilled, because I should hardly mount a barricade now that I know what they are like in reality. And so I know now what an illusion I lived in for so many years. I thought I was a revolutionary and was only an evolutionary. Yes sometimes I do not know whether I am a socialist at all, whether I am not rather a democrat instead.”

June 28th, 1921; “Diary & Letters”; Ibid; p.100

Kollwitz depicted the life of the workers, with its human pleasures – enjoying companionship and children – but she also saw its bitternesses and misery. It is such double-edged tones of Kollwitz’s work that touched some communists. But it is at variance with any ‘simplistic’ notion of any bureaucratically stilted socialist realism. For it was not necessarily brimming with hope. Likely this was one reason the German KPD criticized her work, and even objected to her doing the Memorial of Karl Liebknecht – which the Liebknecht parents had requested of Kollwitz. Their extraordinary argument was that she was not a member of the KPD. Regrettably, such sectarianism was a characteristic strand in the KPD. Kollwitz recorded her reactions in her diary to this rebuke:

“I simply should have been left alone, in tranquillity. An artist… cannot be expected to unravel these crazily complicated relationships. As an artist I have the right to extract the emotional content out of everything, to let things work upon me and then give them outward form. And so I have the right to portray the working class’s farewell to Liebknecht, and even dedicate it to the workers, without following Liebknecht politically. Or isn’t that so? ” Diary & Letters”; Ibid; p. 98

In contrast to the sectarianism of the KPD are the non-sectarian attitudes of Marx and Engels towards the non-party poet Heinrich Heine whose art they admired and published. Or similarly Lenin’s views of the non-party writer Tolstoy.

Apart from seeing close-up the misery of working-class life from Karl’s practice, another stimulus to the theme of death was personal. Kollwitz’s two sons Hans and Peter, both volunteered in WW1. Her eldest, Peter, despite father Karl’s beliefs, had illusions about the “concept of death for the Fatherland’ and “sacrifice”. Some have extrapolated from Kollwitz’s diary that Kathe shared such illusions. (Regina Schulte and Pamela Selwyn; History Workshop Journal, Spring, 1996, No. 41; pp. 193-221).

If so – she later transformed any prior illusions into condemnation. The cycle of “War’ lithographs between 1920-21 warned youth not to ‘volunteer’ and urged ”Nie wieder!” [Never again!].

But increasingly her kernel works became more grimly focused. Death was a terroriser and reaper, but at times was a relief. The relief of an old poverty stricken mother who hears the call of death as a friend. Or the desperate relief of the old man who prepares his own noose in the “Last Resort”. This was a recognition of the grim reality of everyday life – and death – of the workers. (Two of her prints-drawings depicting death are at this web-site http://www.uwrf.edu/history/prints/women/kollwitz.html

Kollwitz’s personal tragedy was transmuted into art under a slogan from Goethe –

“Saatfruchte sollen nicht vermahlen werden.” [“Seed for the planting must not be ground”].

The “seed”, were the children of course. Perhaps her greatest sculptures are those at the cemetery at Roggevelde Belgium, where her son Peter lay with so many others after the inter-imperialist war of 1914-18. Two figures show herself and her husband Karl grieving.

It remains true that despite this vortex, she continued to draw for the working class movement. Up to 1928 she drew her famous posters for aid to Russia, and against poverty in Germany. Many were requested by the international “Workers International Relief “. On 5 February 1933, by now she was the first female director of Graphic Arts at the Prussian Academy, she and Karl took a brave stand against Hitler. Along with 33 prominent co-signators (including Albert Einstein, Henirich Mann and Arnold Zweig) – they endorsed the “Urgent Call for Unity (Dringender Appell für die Einheit) from the International Sozialistischer Kampfbund (ISK) against the Nazis. Tragically this failed. When the Nazis came to power she was sacked and harassed with Karl. She died in Moritzburg near Dresden on April 22, 1945.

Yet when she died, she had not given up on a better world. In February 21, 1944 she told her daughter-in-law Ottolie, that:

“Germany’s cities have become rubble heaps… every war already carries within it the war which will answer it. Every war is answered by a new war, until everything is smashed. The devil only knows what the world, what Germany will look like then. That is why I am whole-heartedly for a radical end to this madness, and why my only hope is in a world socialism… Pacifism simply is not a matter of calmly looking on: it is work, hard work.”

Ibid; p.184

Those words tell us that her concept of socialism was not perhaps, that of a Marxist view. In my view it is of no consequence. Kollwitz defies any single category of ‘Socialist Realist’, and she stands of herself – as a great artist for humanity, and for workers the world over. The Charlottenburg Galleries deserve to be visited by every socialist in Berlin – and those not yet socialists.

Hari Kumar wrote a more detailed piece on Kollwitz in December 2000 for Alliance Marxist-Leninist.