The premise of Vitalis’ book is that oil cannot be the basis of the US economy, least of all, of US national security. There are several minerals (over seventy) which the industrial world needs a constant and secured supply of, and which civilization simply cannot do without. But they are not treated as being as important as oil. This makes us question apparent self-evident truths in news cartels! The average observer has never heard of countries waging war to ensure reliable shipments of aluminum or copper. What is it so special, then, with oil? What is at stake with oil?

According to Vitalis, the story of oil is not the crude matter, but more about suspicous data and poor evidence. Powerful interest groups and lobbies in US corridors of power steer this data toward selling a myth. The fear of failing to ensure a constant supply of oil from the Persian Gulf is supposed to spell a trauma. The myth sits on others. Both science and reason tell us that there has never been a dwindling supply of oil, nor of any other natural resources. As technology advances, new reserves of all types of minerals are constantly discovered. The only way of freeing the US democracy, nay, the very political system and ensuring a solid role-model for the rest of the word is to shed these myths. They cripple US policy planners and ruin the US reputation in the world.

Chapter One ‘Opening’

This sets the stage for revisiting President Bush’s conquest of Iraq in 2003 and check the argument that the US acted on behalf of large oil conglomerates. If so, Vitalis rebuts, the easiest way for the US to access Iraqi oil was to simply lift its own 1990s sanctions on Iraqi exports. So oil companies would have entered the market and the problem resolved. Moreover Vitalis argues, as prices rose in the early 2000s, an abundant hydraulically-fractioned oil made the US a major producer of oil itself.

Now, the US import of oil from the Middle East is around 18 percent. Nevertheless, “Junk social science” (p. 5) keeps a scary narrative aflame. When luminaries and public intellectuals are fixated on their myth of ‘oil-as-power’, the term ‘oilcraft’ recalls witchcraft more than statecraft. Vitalis’ analogy call’s for dispelling confusion and talismanic obsession by promoting a rational understanding of decisions on energy policy. If the only evidence ‘junk’ social scientists provide is price rises, it brings us face to face ‘oil-scarcity ideology’ (p. 6). Vitalis stresses that every statement we encounter in the archive should be taken with a grain of salt.

He proposes we consider three facts: (1) the world is rich of minerals; literally anyone has access to raw materials. Viewing oil-as-weapon is at best incorrect and at worst a ‘chimera’ (p. 14). Instead of embracing a confirmation bias, the abundance should make us question what lies beyond the ‘phenomenal’; (2) the imagined threats to oil supply—even when real—cannot be addressed militarily; (3) oil prices are dependent on other raw materials. A simple comparison of oil prices against other minerals in the long durée—as Roger Stern does—will lead to the conclusion that oil cannot be the lifeblood of the American way of life.

Raw Materialism

Chapter Two posits the idea of a single source as critically important for a national economy is reductionist at best and misleading at worst. Vitalis cites the early twentieth century Columbia School (scholars like Edward Mead Earle and William S. Culbertson). These noted that US policy since 1918 was rooted in “bogeys”, from rapid depletion of natural resources to British monopoly of these resources (pp. 26-7). Back then, like now, there was an industry behind studies, infuriating the public and policy makers alike about such imagined threats.

Vitalis finds the idea of “‘control’ of foreign oil fields” (p. 29) became a priority for the US economy in Americans’ unconscious during the 1990s. Culbertson argued that wars do not emerge from the need to control or ensure extensive supplies of raw materials, but from the need for markets to commercialize industrialized commodities. (p. 32) Embracing mid-nineteen century protectionism triggered bouts of scarcity syndrome.

But a generation or two later these findings from the 1920s were forgotten. The Cold War context made it more likely that the Soviets were ‘threatening’ US access to Middle East oil. Vitalis adds that even Noam Chomsky falls into confirmation bias wherein “the progressives of the 1970s were a pale imitation of their 1920s ancestors.” (p. 55). Progressives kept parroting criticism of American foreign policy without considering where that criticism might be heading.

1973: A Time to Confuse

Chapter Three rereads October 17, 1973 and the alleged OPEC oil embargo, as only a spectacle. For Vitalis under no stretch of imagination did it approximate to a threat of cutting supplies, let alone, an embargo. For in 1973 “only 7 percent of U.S. oil imports originated from the Middle East” (p. 57). Besides, Arab nationalists only expressed a half-hearted and face-saving gestures in the wake of their humiliating defeat against Isarel in June 1967— gestures meant for popular consumption at home only.

Nevertheless, the scarcity-thesis driven by media and ‘experts and intellectuals’, to gain monopoly – made it look as if scarcity is imminent and can usher in the end of the world. Vitalis discusses the five hundred page report (David S. Freeman’s ‘A Time to Choose’) released when Americans were experiencing long lines in gas stations. The report made it super easy to conclude that the long queues resulted from the much-publicized shock spelling serious disruptions of supply, presumably orchestrated by the Arab Embargo.

In reality, OPEC “sought a fairer share of the windfall.” (p. 64) To protect local crude producers from the unstable market, the US government had used a preferential tariff with local crude producers. The Nixon Administration, however, decided in 1971 to reverse the preferential tariff policy and open the US market to non-American producers. This new policy, not OPEC’s action, explains the interruption in supply and long queues. Far from disrupting supply, Arabs were terrified of losing their market shares.

No Deal

Chapter Four elaborates on the motivating principle behind the myth that stipulates the invisibility of oil for the American policy maker. It is definitely the key chapter as it uncovers the motive behind portraying oil as the bloodline of the American economy. Vitalis notes that this myth could not become as intense as it is now without the ‘fantasy-embraced-as-history’. Given their nefarious stature after 9/11, the Saudis, or Al Saud, more exactly: the ruling oligarchs of Saudi Arabia – invested heavily in painting themselves as peace-loving and reliable suppliers of oil for US economy. They went as far as inventing a presumed memorandum of understanding (a deal) between King Ibn Saud and President Franklin Roosevelt on board the destroyer U.S.S. Qunicy near the end of the World War II. The author finds no trace of this presumed deal in the archives. But it supposedly stated that the Saudis would ensure reliable shipments of crude and the US, would guarantee the protection of the king and his dynasty.

Vitalis adds: “The only problem is that no account of U.S.-Saudi relation for the next fifty years said any such thing.” (p. 87). But “The Saudis, the PR firms, and their many friends in Washington would milk the meeting with FDR for all it was worth after 2001.” (p. 91). Vitalis counts this Saudi fabrication among the latest in the arsenal of forgeries specifying the centrality of oil.

Interest groups profit from recycling oil dollars in the US economy through purchases of US treasury bonds, consumer goods and, of course, armament bills with astronomical price tags. That is how, it is for the long-term interest of the US to distance itself from a retrogressive and degenerate monarchy. That proximity does a considerable damage to the status of the US as a superpower. The crumbling of the Saudis’ rule will be an event that will boost, not hinder, the US supremacy or at least its leadership credentials.

Breaking the Spell

Chapter Five concludes Oilcraft. Vialis starts by underlining that “popular and scholarly beliefs about oil-as-power have no basis in fact” (p. 122). But the irony of the myth is that policy makers who sincerely want to break this fixation can do little to break the immanent structure whereby oil is received as invisible. The assumptions are so powerful that any attempt to go against them end in discrediting, or ridiculing, the credible policy maker. The first step is getting the scholarship correct, never allowing unchecked opinions to pass for knowledge. Knowledge starts by first, making sure that crude producers have no choice but to sell their outputs. Before harming the US economy, cutting supplies will strangle their own economies and destabilize their hold on power.

Second, one needs to be certain that besides the fact that deploying an army to protect crude supplies cannot be tenable and efficient, the deployment itself raises tensions and causes supply interruptions. Third, the Middle East is a volatile space, and it does not behoove a superpower to be constantly dragged into the mess out there. Fourth, by the same depleted logic of scarcity, why does the US not go and chase bauxite, tungsten, tin, rubber lest they are all appropriated by other powers? Fifth, there is a fallacy by which the degenerate Left sells its credentials: which is as soon as soon as the US steps out of the Middle East, “the fossil-capital-led order” will fall all on its own; allowing an era of plenitude to automatically emerge.

Finally Vitalis notes that “Oilcraft today [has] hijack[ed] the mind of the scientifically literate” (p.128), the average person believes oil passes as an explanation for almost all wrongs with the world. He believes that Saudi money should not be allowed to finance studies. Vitalis rightly says “the paid-to-think-tanks” (p. 131) will only bring pseudo-science, more confusion and befogged policies. Moreover the propaganda which the funding generates covers for the asphyxiation of liberties in the Middle East and the world at large. In the end, Vitalis rightly addresses the US policy maker: “why fear an Arabia without Sultans?” (p. 133)

Conclusion

Vitalis finds that well-intentioned and respectful policy makers and advisers are crippled by enduring myths. These myths have taken a dimension that is larger than life. He is certainly correct that the journey for undoing their effect start with unbiased research. But there are instances where Vitalis’ suspicion of the ideology that “oil-is-anything-but-powerful”, recalls the theory that colonies cost metropolitan centers more than the latter could squeeze value out of them.

Perhaps missing in Vitalis’ discussion is how during the time where capital expansion needed nationalism, oil was treated (and for good reasons) as the lifeblood. Vitalis indirectly calls for updating sedimented thinking, since capitalistic growth since the 1920s (exactly after WWI) is not conditioned on the old mystique view of oil-as-bloodline, given the abundance of supply. Producers simply cannot afford to withdraw crude from buyers lest they risk losing their share in a highly competitive market. Similarly, no major power can hinder access to oil because oil remains evenly available everywhere.

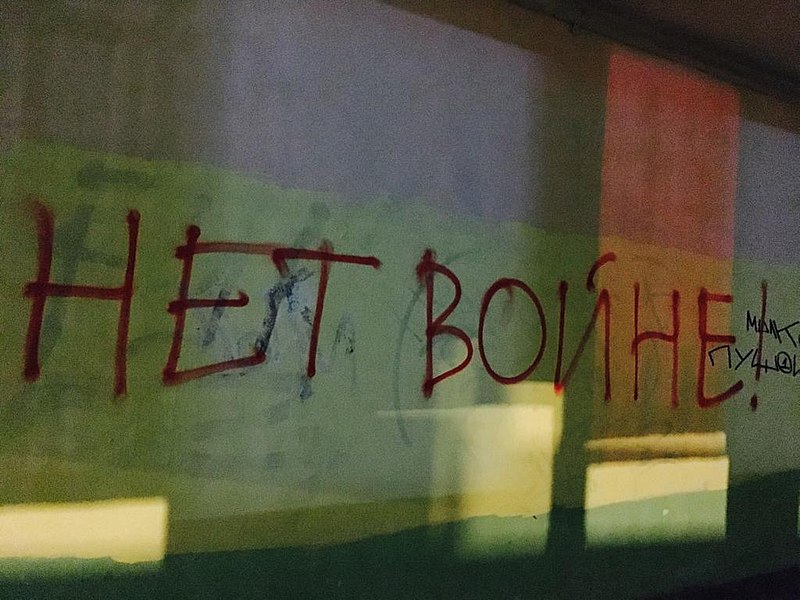

Vitalis’ analysis in Chapter Four dwells on the corruption of the Saudis and their dizzying pace of change ‘from camels to Cadilliacs’ (p. 95) paid for by oil rent, may sound racist and inconsequential in the overreaching impact of oil wealth. Oil wealth decides less their conservative outlook but more significantly intensifies their adamant predisposition against an egalitarian polity all over the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. The counter revolutions that quelled the uprisings of the Arab Spring both in 2011 and 2019 were engineered and financed principally by their medieval outlook. Vitalis notes that with recycled petrodollars the Saudi acquired F-15 jets which since March 2015 bombed civilians in Yemen. But he could have also noted that worse than F-15s is the regressive and ultra-conservative brand of the faith, whose sole agenda is the crashing all social movements which moved towards a lifestyle free from the dictatorship of oil.

Overall, there are instances where Vitalis’ debunking of myths such ‘oil-as-power’ falls into the right; and others where which falls more into the left. At times he can even be counted as a devout communist. But this is the quality of great scholarship, where he passionately elucidates his points regardless of class or ideology. Indeed, Vitalis embraces his mission to eradicate facile portrayals. Masquerading beneath so-called ‘self-evident conclusions’ lies not only tperpetuating mistaken decisions but squandering of the US taxpayers’ savings as well as the subaltern of the MENA chances for a future in dignity.

Vitalis, Robert. 2020. Oilcraft: The Myths of Scarcity and Security that Haunts US Energy Policy. Stanford University Press; pp. 240 pages; Paperback: $22.00; Hardcover: $22.47; ISBN-10 :1503632598; ISBN-13: 978-1503632592