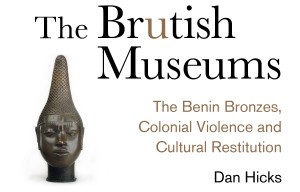

The preface to the paperback edition of Dan Hicks’s The Brutish Museums ends with a suggestion: “you might just now skip ahead and take a look at Appendix 5. Ask yourself how near you are right this minute from a looted Benin Bronze.” For me, the answer was easy. Appendix 5 is a provisional list of museums and galleries that hold objects looted from Benin City in 1897. The Appendix lists 24 German museums, including Berlin’s Ethnologisches Museum and Bode Museum. While the UK and the US each have more museums on the list, Appendix 1, showing the distribution of bronze plaques across them, places the Ethnologisches Museum at the top. 255 plaques are kept in the Humboldt Forum, compared to the 192 that can be found in the British Museum, the runner-up.

The usual story about how the Benin bronzes ended in places like Berlin is retold in museum exhibitions around the Western world. In January 1897, a British delegation went to meet with the Oba of Benin in what is now Benin City, Nigeria. The delegation was ambushed and killed almost entirely, so in February a “punitive expedition” brought an end to the Kingdom of Benin. Thousands of bronze, ivory, and coral “fetish” objects were taken as war bounty and spread across museums and private collections.

Published by Pluto Press in 2020 and released as a paperback in 2021, its purpose is to show how this story’s retelling is part of the colonial violence that, according to Hicks, is continued and reenacted every day as these museums open their doors to visitors. Hicks would know: he is Curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford (10 bronze plaques, according to Appendix 1), and Professor of Contemporary Archaeology at the same University. Invoking Swedish author Sven Lindqvist’s encouragement to “dig where you stand,” Hicks offers his book as an “Anglo-centric” account of the violence of exhibiting colonial loot.

the “motto” that Hicks repeats throughout the book: “as the border is to the nation state so the museum is to empire,” both racial technologies of categorization and differentiation.

Hicks reads archival sources and critical historiography to offer a different story than that on the labels in his own museum. His book skillfully navigates the complex internal politics of British colonial companies and protectorates to untangle the threads of colonial expansion in West Africa. Rather than an ambushed peaceful delegation, Hicks shows how the January 1897 clash was part of British officials’ concerted efforts to legitimate military action against African rulers who did not engage in trade on colonial terms. The punitive expedition was also not a mere defensive reaction. Hicks places it within what he calls “World War Zero:” a campaign of “small wars” (the British colonial euphemism) that together amounted to a coherent politics of killing, destruction, looting, and integration into a system of extraction and exploitation.

At the center of Hicks’s narrative are death, loss, and a “theory of taking.” The Benin bronzes, of religious and royal significance, were uprooted and commodified into “primitive” art. They were stolen by the British who participated in the military expedition and sold across Europe and North America. The usual story is that they were salvaged to be preserved and protected, but Hicks insists that they were war bounty in a landscape of “ultraviolence”. Part of this landscape was the anthropology museum, developing at the time as the enactor of a worldview that legitimated the new height of Empire. This is encapsulated in the “motto” that Hicks repeats throughout the book: “as the border is to the nation state so the museum is to empire,” both racial technologies of categorization and differentiation.

By tracing the history of the bronzes throughout the 20th and 21st centuries Hicks also traces the history of the anthropology museum. Although the book does have a penchant for literary turns of phrase and catchy theoretical coinages, it skillfully intervenes in debates about material culture and museal studies without losing the reader in esoteric details. Hicks shows, for instance, that the “universal museum” of the early 21st century is once again a legitimation of imperial expansion. It was born as the Iraq war was drawing new civilizational boundaries, situating the West as the legitimate protector of universal human values and of universal human art.

Nevertheless, Hicks sees his book as a “defence” of the anthropology museum, a vision of the museum without stolen loot and as a space to critically reflect on history and colonialism. He references the efforts toward restitution that have come out of Nigeria, Europe, and North America. More work is needed, he argues, if his book is truly to have been written at the beginning of a “decade of returns,” as he titles his afterword. Work that carefully traces the trajectory of stolen objects, that names names and points fingers. Work done from within the museums that continue to enact colonial violence, not left only to Nigerian institutions and activists. And work that offers material, real solutions for restitution, not just neocolonial musings on how art needs to be protected and to reach a universal (read “white”) audience.

Hicks’s merit is being able to transform his book, ostensibly about the Oxford museum at which he works, into a powerful argument about the global endurance of colonialism. Even Germany finds its deserved place in this Anglo-centric story. There are the expected references to the 1884 Berlin conference (which carved the European zones of influence in Africa) and the Herero and Nama genocides (conducted just a few years after the Benin expedition). But Imperial Germany had a central role in the spread of the Benin loot. German anthropologists were some of the new museums’ principal developers. At their behest, Benin bronzes were already being acquired through the Empire’s Lagos consulate in 1898, and a significant number of the estimated 10,000 stolen objects ended up in Berlin, Hamburg or Munich.

If the stolen Benin objects are, in Hicks’s words, “ten thousand unfinished events” it is up to students, historians, curators, and activists to steer their futures toward restitution… But, as Hicks is aware, we must not allow intellectual work and scholarly activism to turn into self-congratulatory complacence

The connections did not stop in the 19th century. Neil MacGregor, a former director of the British Museum and one of the main targets of Hicks’s critiques, also served as the funding director of Berlin’s neocolonial Humboldt Forum, home to the Ethnologisches Museum and forced home to the Benin bronzes. Resistance to the Forum’s construction and calls for its defunding are part of Germany’s more and more urgent reckoning with its own enduring colonial violence – a reckoning that has drawn angry backlash. Writing recently from Berlin, Hicks sees both hope and risks at the horizon. Hope because Nigeria and Germany have signed an agreement that will see the return of 1,130 items looted from the Kingdom of Benin (similar German pledges have been made to Namibia, Tanzania, and Cameroon). Risks because, as Hicks tells from his visit to the Humboldt Forum, this is just a beginning. A beginning that still takes place on the grounds of Eurocentric, white universalism, and can still be co-opted into bolstering, rather than undoing, colonial violence.

Qualified hope is the outlook of The Brutish Museums. Its afterword begins by again addressing its readers: “This is the kind of book where the reader has to write the conclusion by taking action.” If the stolen Benin objects are, in Hicks’s words, “ten thousand unfinished events” it is up to students, historians, curators, and activists to steer their futures toward restitution. In these undecided trajectories, as Hicks quotes from researcher and curator Suraya Kassim, “there is a danger (some may argue an inevitability) that the museum will exhibit decoloniality in much the same way they display(-ed) black and brown bodies as part of Empire’s ‘collection’.”

This danger is present in The Brutish Museums as a cultural product. The paperback’s cover declares it one of the “NEW YORK TIMES 2020 Best Art Books,” an endorsement that has probably increased its sales in museum bookshops. And when the reader turns the book around and looks at the fine print, they can see that the picture of a bronze head that adorns the cover underneath this blurb is copyrighted to “The Trustees of the British Museum.” Considering Hicks’s insistence on the Maxim machine gun and photography as key technologies of 1890s’ colonialism, this is not just ironic. It is proof of Hicks’s own thesis about the temporal expansion of colonial violence into the present.

For all interested in this (and it should be all of us), or interested in issues of art, justice, and restitution, The Brutish Museums is an important book. But, as Hicks is aware, we must not allow intellectual work and scholarly activism to turn into self-congratulatory complacence. And we must not forget that Hicks writes from and for the metropole’s centers of power. No number of self-aware, critical books can be a substitute for full restitution.