Visiting my “homeland” after 13 years was, among other things, enlightening. For years I hesitated to express any strong opinions on Pakistan because I did not want to become the stereotypical diaspora Pakistani throwing stones at the glass slum from whence I came. I had harboured my suspicions for years about how plainly terrible existence in that country is. Witnessing the prevailing attitudes in person along with Instagram’s algorithm noticing, with Eye-of-Sauron alertness, that I might have some relationship to the country has given some confirmation to my suspicions.

My “for you” page is flush with content from Pakistan that basically falls under three categories: celebrity gossip, politics, and what I would call gristle to the mill of popular libidinal obsessions. The last category obviously needs some explanation. I’ll share an exhibit.

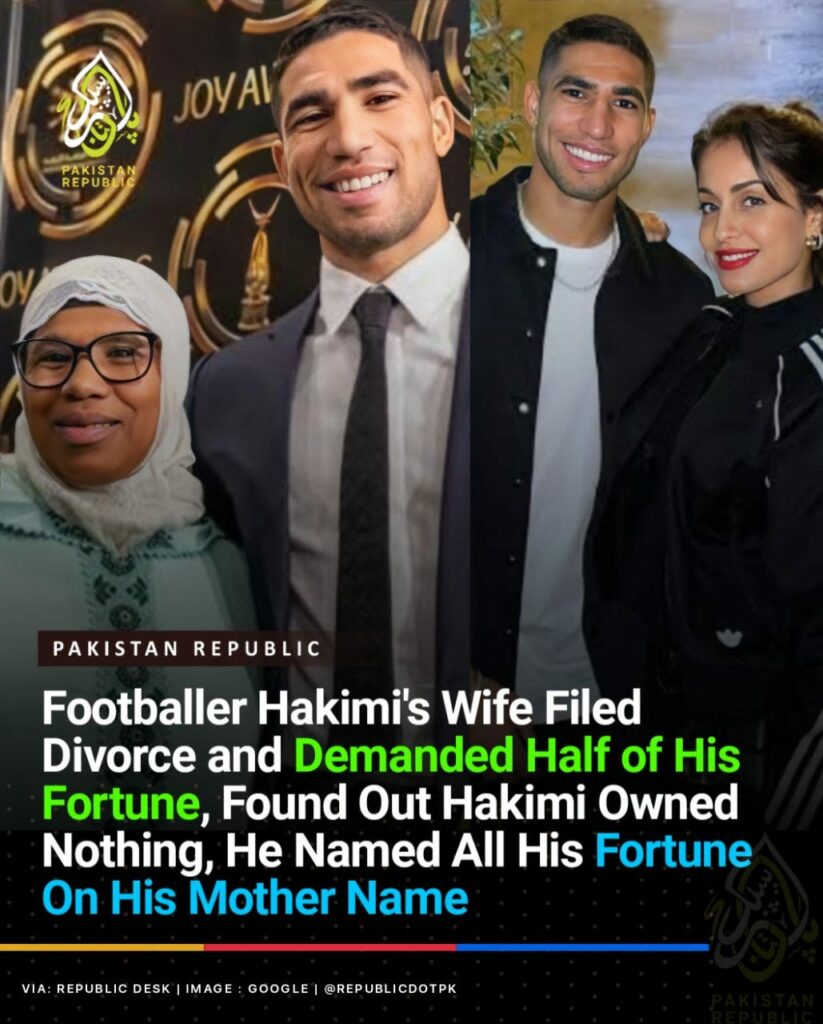

This graphic is the one that nudged me over the edge to write a piece on Pakistan. Notice the framing of a wife “demanding” half of his fortune and the revelatory tone regarding him “dodging the bullet” by putting everything in his mother’s name. The footballer plays for Morocco and Paris Saint-Germain so one wonders why anyone in Pakistan should care in the first instance, but more on that later.

Three essential cultural declarations are being made in this image: fuck women who make any demands on men; never, ever become independent from your mother; a win for any Muslim is a win for Pakistanis. It should be added that the above footballer is also facing charges of raping a woman, but mentioning that may undermine these three declarations.

I can’t overstate the third, implicit declaration. To fully understand it, one has to have a reasonable answer to the question: What is Pakistan?

To begin our inquiry, it helps to know what Pakistan isn’t. Pakistan is 1) not a real country 2) not a republic, and 3) not on the verge of a sudden, fantastic boom of prosperity.

Pakistan is better described as a military with a state glued to it; but the glue is not very good so the military and the state seem to hang on to each other for support, looking like a very uncomfortable, disjointed alternating piggy back ride.

Pakistan is said to be composed of four major provinces. Also untrue. It is composed of half of a province with the remaining half in India (Punjab), a city with a province glued to it (Karachi and the lands of Sindh), and two regions of land that would would much rather secede but are dragged along for a very uncomfortable ride (Balochistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa). The national language of Pakistan is Urdu, a language popularised in the old royal courts of New Delhi (India), Lucknow (India), and Lahore. Nobody speaks it as a primary language, except only to poorly understand people who speak a different regional language than oneself. The language is often referred to as a language of armies — a composite of many regional languages.

Pakistan used to have another “province” called East Pakistan, modern day Bangladesh, which was separated by about 2000 kilometers from the other so-called provinces. How did that work you might ask? Well, it didn’t. The moment East Pakistan exerted some national sovereignty, the Western half invaded the country, carried out a campaign of rape and genocide, and promptly got their asses beat when the military reality of invading a country 2000 km away surrounded by your much bigger arch rival caught up with them.

Pakistan is also the 5th most populated country in the world, behind only China, India, the USA, and Indonesia. If Bangladesh had remained part of this strange contraption masquerading as a state, it would only be behind China and India in the population league. The more I think about Pakistan, the more flabbergasted I am that people refer to it as a country. The closest analogue I can find to this fissiparous construct is Belgium, but Pakistan makes even Belgians look as unified as the Swiss confederation.

Pakistan is also trying to get a bailout from the IMF, its thirteenth (yes 13th!), to help with its dire economic situation. Currently, the total inflation rate is about 35%, annual food inflation is about 50%, and the balance of payments crisis is so severe that the country is living, quite literally, paycheque to paycheque, with many declaring the country effectively bankrupt. Foreign reserves of currency in Pakistan are barely enough to afford import bills for 4 weeks. It is one giant cauldron of misery.

And then my brother went to die there and dragged me to come witness this misery to pay for my sins.

So how is this not-a-country run exactly? Let me present exhibit B.

Now I don’t know about yourselves dear readers, but when a man in a military uniform gets in front of a mic and tells me how the people, as opposed to him I guess, have all the power, I don’t feel very assured. Even less so when I regularly see the same man in a uniform regularly be the subject of the headlines every day. And I am not joking at all when I say that writing this blog and making this statement might actually get me abducted (or worse) if the wrong person reads this and gets very annoyed.

It is precisely in this confluence of immiserating conditions that Pakistanis must seek out a self-soothing narrative to act as a palliative for their aching souls. Religious institutions with views ranging from extreme to ISIS begin to function as a ‘third sector’, providing food and indoctrination disguised as education. Islamic fundamentalist parties, organised like clerical fiefdoms, lambast the degeneration of Pakistan from a once proud and optimistic nation sinking due to its own abandonment of “true” religious values. Their influence can be exemplified by the evolving image of Imran Khan’s wives.

Former Prime Minister, philanthropist, and cricketing hero Imran Khan was first married to Jemima Goldsmith — daughter of an Anglo-Irish aristocratic mother and an ultra-millionaire father. Khan himself was seen as a modern, cosmopolitan Pakistani who professed a sincere dedication to seeing his country prosper. That got beaten out of him eventually and he is now married to a woman who is regarded as a faith healer — a sort of evangelical Muslim.

Imran Khan is the most popular politician in the country. He was Prime Minister until April of 2022, when conflicts with the military top brass and his own fractious coalition created the conditions to have him ousted, a move that has made him even more popular than before. In any remotely fair election, it is likely he would win an even stronger mandate than before. However, much of his success is built on building a personality cult, demagoguery about imported governments, generous servings of religious conservatism, and, worst of all, alliances with influential defectors from the corrupted ruling class that he spent all of the 90’s and 00’s railing against.

His opponents are two brothers leading an offshoot of the Muslim League, the founding party of Pakistan, who both owe their rise to power to Pakistan’s longest reigning military dictator, General Zia-ul-Haq. Zia-ul-Haq, in his successful 1977 coup backed by Washington, had the founder of the other major opposition party (the Pakistan Peoples Party), Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, judicially executed. The current leader of that party is Ali Bhutto’s grandson Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari, whose mother (and Ali Bhutto’s daughter) Benazir Bhutto was herself the former Prime Minister, and eventually assassinated.

If you are a little confused, you wouldn’t be alone. The ruling class of Pakistan is a politically incestuous mess that takes turns being dominated by the economic and political might of the military. It is ironic that the most organised, wealthy, and popular political party in Pakistan is never on the ballot.

And then the economic question arises. What does the 5th most populated country in the world do to survive economically? How is it that it continually needs to go around begging international creditors every time there is a shock in the world system?

Without going into too much detail, Pakistan’s economy is built on exporting textile products, sports goods, remittances from the diaspora, and land speculation. That’s it really. The country is uncompetitive in the international export markets, suffers from a chronic lack of investment in its industries, and the agrarian sector is plagued with large concentrations of land that are ultimately under-productive. There has never been a comprehensive land reform in the country, barring one abortive attempt during the period of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

International aid and loans that the state has frequently resorted to for survival are heavily taxed by its kleptocratic rulers, so that much of the money never gets spent on what it was meant for. Additionally, this corrupt state machinery becomes organised like a pyramid that distributes the fruits of corruption to maintain its internal cohesion, at the expense of the greater national interest. The single exception is investment in the military. As a share of the national budget, Pakistan spends more on its military than the two most belligerent countries on the planet.

These statistics are astounding even to myself. I knew things were bad, but I never thought they were this bad. It’s only after visiting the country, hearing the attitudes of the people, seeing the abject poverty that I began to understand what a mess we had left behind. Or so I thought. My brother was not a product of that world, but he was subject to it’s gravitational pull.

But that’s for another time.

Frequently, you hear people in Pakistan talk about its long unfulfilled potential. About the natural resources littered across the country, about the talent of its people, about the transformative power waiting to be unleashed if only a few select conditions were fulfilled. One or two weird tricks that, if mastered, will make Pakistan a hegemon.

Pakistan has never been invaded by a foreign power, yet it is always rattling its sabre to psyche itself up for an invasion from India, a country many times larger and richer than itself. A country it would have no hope of ever defeating militarily.

Pakistan itself is a country riven by sectarian, ethno-cultural, and economic stratification. Sunni Muslims view Shia Muslims with suspicion, both share a hatred for Ahmedis (best described as Muslim Mormons) and the small pockets of Christian and Hindu minorities that remain in the country. A country that is nearly 97% Muslim yet manifests constantly the uncertainty of its Muslim character. Urban dwellers are divorced from the realities of the agrarian mass of the country. Clan based social organisation still prevails, particularly at the apex of society, jealously guarding its wealth and privileges from dilution.

The absence of a national character creates a vacuum. The state was founded on negating an Other — namely the Hindu majority of India. This was achieved not through some war of national liberation or a collective struggle for political and civil rights, but rather behind closed doors negotiated by a coterie of pseudo-aristocratic landowners in charge of the Muslim League, itself a political formation stitched hastily together to respond to the influence of the Indian National Congress.

As soon as the state was born, it’s raison d’etre vanished. The only remnant being the Muslim-ness of the inhabitants. It is for this reason that the lives of Muslims of every shape, colour, or stripe become fodder for the aspirations of its people. When Pakistanis are not obsessing over the past glories of Muslim empires or peoples they have little relationship to, they are fulfilling their vicarious fantasies through half-baked info-tainment about Muslims abroad. A favourite of the genre is when a white person converts to Islam, as if doing so is a direct benefit to the interests of Pakistanis.

Better days are always on the horizon, and those who do not live long enough to see them, get to feast on the pie in Allah’s sky. Except those unbelieving *insert name of sect or religion you hate*. Unable to accept themselves as wretched victims; unable to accept the historical deceits underpinning their nation; unwilling to embrace secular modernity; suffering from economic woes and cognitive dissonances; Pakistanis are cursed to endure a never ending paralysis that necessitates the palliative relief of many-flavoured opiums.

Acknowledging the harms and the pains of this reality threaten to sink me into depression. No amount of privilege, no amount of distance, no assumed nationality is sufficient to shield me completely from it. I cannot bear to think of what routine sufferings are inflicted on people that are my compatriots. Yet I cannot see any benefits in assiduously ignoring the facts of our national quandaries. Pakistan is functionally a failed state, one that is waiting for fate to deliver its quietus.

This article originally appeared on Ali Khan’s Blog