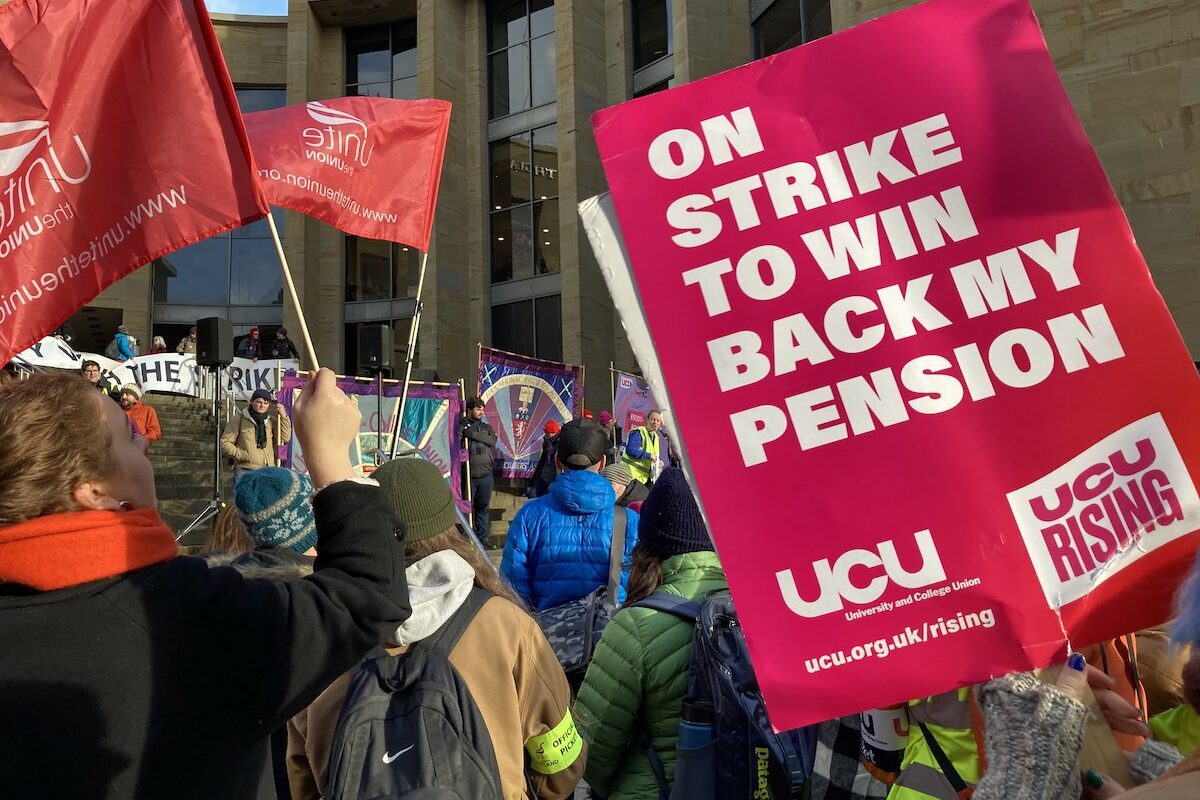

The current strike wave across Europe is part of a revival in workers’ confidence and workers’ struggle. There have, in recent months, been important strikes in Germany and in Portugal; Britain is witnessing its most sustained wave of strike action since the late 1980s, and France is experiencing perhaps its highest level of workers’ struggle since 1968. On May Day this year, over two million people protested on the French streets as part of the movement against the government’s attack on pension rights. On the 7 March, there was something close to a general strike—with most rail services and much of the public transport network stopped, schools shut down and striking energy workers blockading refineries.

Strikes are a basic expression of the collective self-activity of the working class. For Karl Marx, unions could, at their best, be organising centres for the working-class struggle, “schools of socialism” as he put it in an 1869 speech to German workers, in which workers train themselves in the fight against capital. However, unions are also complex organisations, often with powerful bureaucratic tendencies that can act as a brake on struggle. This article offers a brief attempt to analyse the strike wave we are seeing from a Marxist perspective, focusing on the struggles in Britain, where my own activity is focused, exploring the tensions within the unions.

Drivers of the strike wave

There are always specific causes of strike action. In France, the trigger has been attempted pensions reform. However, we also see common drivers in instance of action. First, there has been a lengthy build-up of discontent due to wage stagnation and growing inequality. In Britain wage growth has stalled during the past decade and a half of Conservative rule with many jobs becoming more precarious.

Second, there is the more recent impact of Covid-19. The pandemic highlighted the central role workers play in the functioning of capitalist societies. Many workers expected to receive some recognition or reward for their sacrifices once lockdowns ended. They received none. Some important strikes in Britain involve workers whose labour was key to sustaining society during the pandemic, including health workers, schoolteachers, Amazon depot workers, dock workers, rail workers and postal workers.

Third, there is of course the immediate issue of the cost-of-living crisis. In the case of Britain, any worker who received a pay rise below about 15 percent over the past year experienced a real-terms pay cut. Some workers in the private sector were able to blunt the impact of inflation a little by securing pay rises, often without strike action, but in the public sector, and other workforces covered by national pay bargaining, things have been far worse. Whatever the specificities of the various disputes in Britain, inflation and pressure on pay has been the major driving force.

The halting British strike wave

The wave of action in the UK began with a rail workers’ strikes in summer 2022. Rail workers are a relatively small but well-organised and powerful group. The leader of the RMT rail workers’ union, Mick Lynch, quickly became a celebrity figure on the left, arguing a basic class politics in the face of a series of patronising TV and radio interviews.

Soon the Communication Workers’ Union (CWU) also began to take action, in both telecommunications and the postal service. The CWU also played a central role in launching Enough is Enough—a broader campaign over the cost of living. With other unions, in education, the civil service and health, joining the strike movement in the autumn and winter, there were big Enough is Enough rallies in many cities. However, just as these groups appeared to be developing a base of support, there was an effort by those running the campaign nationally to clamp down on groups that appeared too radical or diverged from its preferred approach. The project was strangled by the union bureaucracy and now plays little role in most areas of the country.

The pattern of national strikes has also revealed important limitations. They have largely taken the form of episodic actions, lasting a single day or, in a few cases, a few days at a time. On the rail network this could have some impact. Similarly, in schools, which, as well as providing education, are also sources of free day-care, allowing many parents to work, there is a significant economic and social impact when strikes take place. However, in neither of these cases have the episodic strikes been sufficient to achieve major victories.

In other areas—such as the postal service or in the universities—short strikes are even less effective. Managers can easily plan around these actions. In the universities, my own union, the University and College Union (UCU), has undertaken an unusual amount of strike action in recent years. Most of our action has consisted of multi-day strikes. However, these mobilisations have not proved terribly effective and, as each day of action involves a loss of a day’s pay, this can breed cynicism among some union members, despite the efforts of activists maintain enthusiasm. In the civil service, the stop-start pattern of strikes has allowed the PCS and other unions to obtain talks with the government, but it is unlikely that any offer will come close to what members desire.

Even in France the pattern is for unions to call “days of action”, rather than indefinite strikes, despite two-thirds of workers there saying they would support indefinite action.

Escalation

In Britain, as in France, there have been calls from a section of the union membership for escalation. Arguments for escalation have taken two forms: the coordination of strikes across unions and the extension of specific strikes to prolonged or even all-out action. While both forms of escalation are welcome, on occasion the former has been counterposed to the latter, with some union leaders showing enthusiasm for coordination without mapping out a strategy that can win their own dispute.

The push for coordination is at least an improvement on the approach of some union leaders, such as those from the Royal College of Nursing (RCN), who have resisted joint strike action. This appears to reflect the belief that health workers enjoy such a high level of popular support that they can secure special deals from the government. The leadership of the National Education Union (NEU), which organises in schools, has, by contrast, been among the keenest on coordination. The NEU placed itself at the centre of a couple of important days of coordinated action in 2023, where half a million, and then close to a million, workers struck together. There were large joint union rallies in many towns and cities, forming a welcome celebration of working-class resistance.

However, less progress has been made on the more important form of escalation—extending the action. The power of this tactic is seen in some of the local disputes in recent months, driven by groups of workers with a more militant approach. For instance, 580 dock workers on Merseyside recently won pay rises ranging from 14.3 to 18.5 percent after five weeks of action. Some 250 bus drivers in Hull won 20 percent after four weeks or continuous strikes. Criminal barristers won a 15 percent increase to their fees after calling all-out indefinite strike action, with a large minority seeking to hold out for a bigger settlement when the deal was put to members.

This approach—prolonged, hard-hitting action—has not been replicated nationally. The executive of my own union, the UCU, did vote to move to all-out strike action across the universities (ie action with no designated end point). Again, this reflects the extent to which the UCU has taken strike action in the past few years. In this context, the UCU has developed an unusual degree of internal debate and a militant minority prepared to challenge the union leadership—and, to some extent, that is reflected on the union’s executive. However, in this case, the UCU’s general secretary, Jo Grady, managed to overturn the executive’s approach. This involved her making an appeal to more conservative layers within the union, through an electronic survey of members, publishing an alternative plan for action, which was sent to every member directly, and holding a branch delegates’ meeting, based on a discussion of confused and often leading questions. Through such manoeuvres Grady and her supporters managed to convince enough members of the executive to retreat on their plan for all-out action.

The UCU executive instead agreed to 18 strike days over two months but the opportunity to break the pattern of episodic action among unions at a national level was sadly lost. Moreover, in mid-February, UCU leaders “paused” strikes—without consulting members, the executive or even the union’s elected negotiators—announcing a “two-week period of calm” and retrospectively seeking support through another e-ballot. There were also attempts to persuade members to accept a lousy deal over pay, which would have amounted to a 15 percent pay cut over two years, which members rejected when balloted.

Poor pay deals have, though, become the norm. Typically, these are two-year deals—offering workers a couple more percent on their 2022-23 pay deal and around 5 percent for 2023-24. These are often presented to members as a victory, or at least “the best we can get”, even though they fall well below what would have been possible with a more determined programme of strike action. Strikes are continuing in some parts of the rail services, and among doctors and nurses within the National Health Service. Other groups such as post workers, university workers and teachers remain in dispute, and others groups, for instance in local government, are balloting to take action.

However, many groups of workers have grudgingly accepted poor deals to end their disputes. Episodic strike action is clearly not leading to breakthroughs that can reverse this pattern.

This is the first part of a speech Joseph should have given at the Marxismuss conference in Berlin before he was unfortunately taken ill. Reproduced with permission. Part 2 will be published on theleftberlin.com tomorrow.