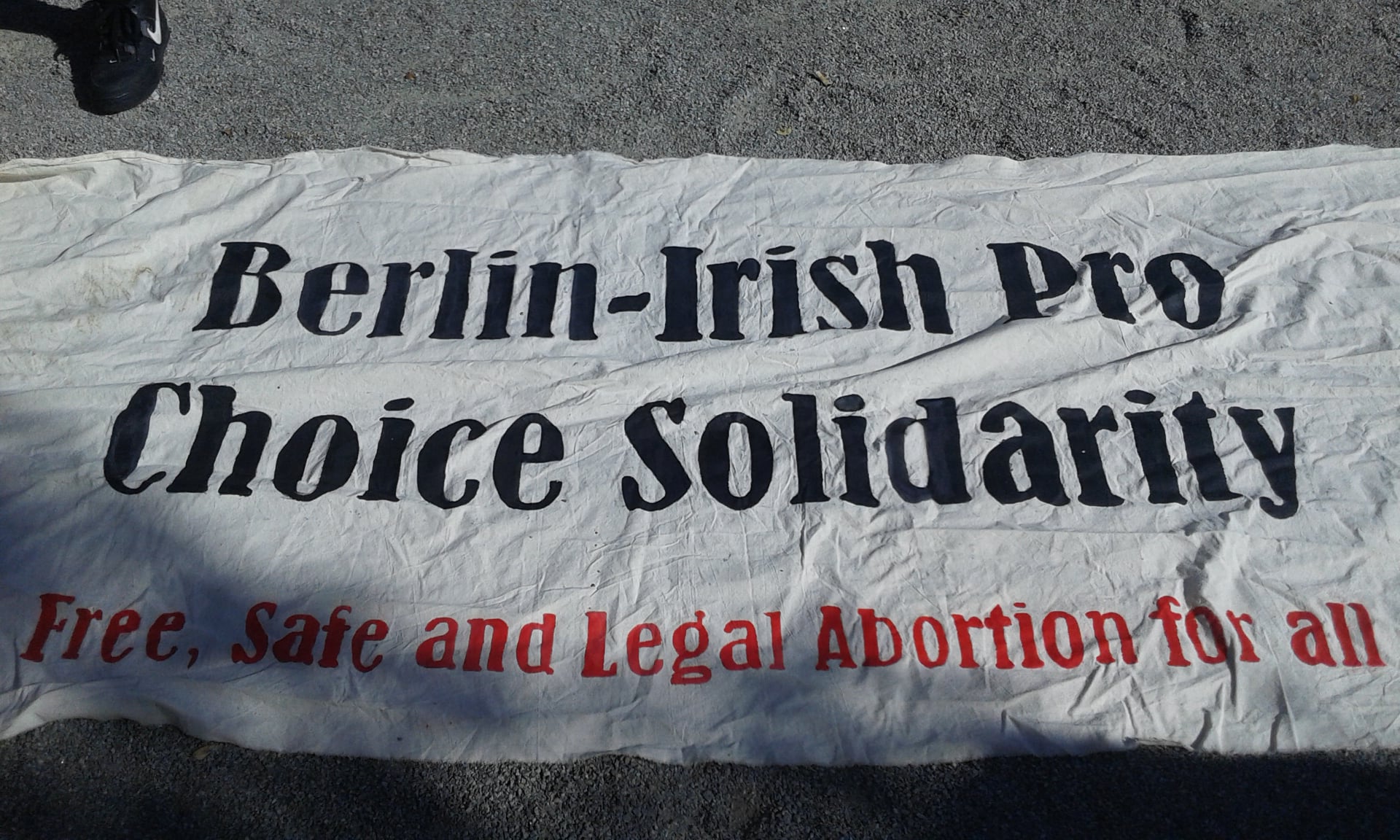

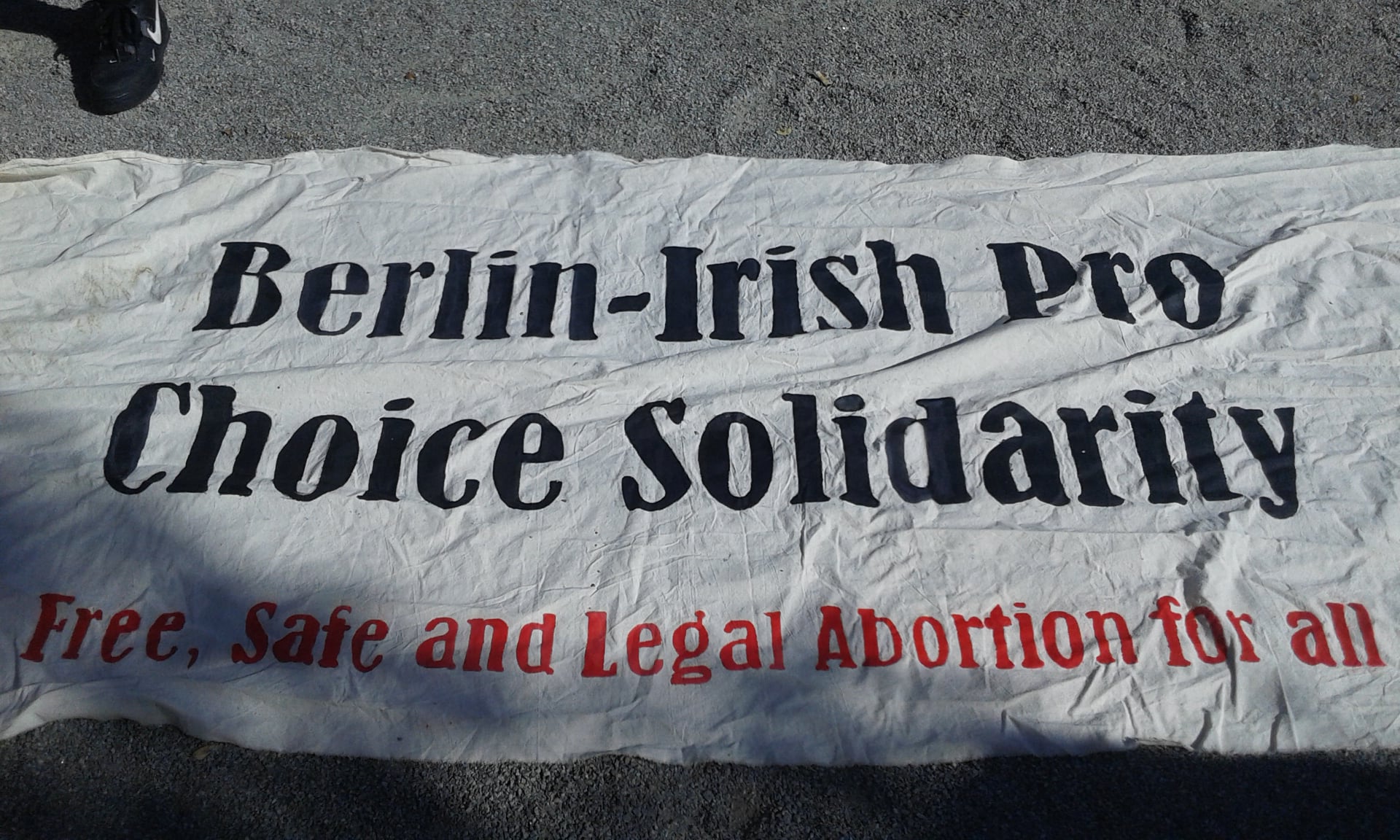

photos by Phil Butland, Kate Cahoon, Dimitra Kyrillou and Marie Rose. Reproduced with permission

photos by Phil Butland, Kate Cahoon, Dimitra Kyrillou and Marie Rose. Reproduced with permission

Phil Butland

30/09/2019

photos by Phil Butland, Kate Cahoon, Dimitra Kyrillou and Marie Rose. Reproduced with permission

Comments on “Germany’s Future Is Being Decided on the Left, Not the Far Right” by Noah Barkin in “The Atlantic”, August 28, 2019 (used by portside, August 29)

True enough, as this article points out, the German party called The Greens has certainly soared to an amazingly strong position in the political spectrum; it is even grasping for the very top job soon to be vacated by Angela Merkel, with some hope for success. But placing it on “the Left” is not at all so certain. It may be green in its environment program but in terms of political hues, unlike its American namesake, it is by no means so clearly in the red, or leftist, rainbow sector.

The party began nearly fifty years ago as a radical, angrily-attacked antidote to the stolid West German scene. With its feminist, anti-establishment, equalitarian and above all environmentally conscious words and actions, symbolized by wearing sneakers to government receptions and hand-knitted sweaters to parliamentary sessions, its break with traditions was almost a shade of Woodstock ten years earlier.

But its “realo” faction outscored its “fundis”, pragmatic “realists” beat leftist “fundamentalists”. When it joined a government coalition with the Social Democrats on the federal level in 1998, its radical aspects retreated. The major break came when Joschka Fischer, its leader and foreign minister, sent German bombers against Serbia, a brutal war crime based on lies (now increasingly coming to light). It was the first time since 1945 that Germans in uniform (in planes) killed people outside their national borders, and was made possible by German unification nine years earlier – and by the Greens. In its years sharing the helm of state, until 2005, a whole series of measures were also passed against Germans at home –hitting hardest at the jobless and at pensioners, while the wealthy were not just spared but richly rewarded with a multibillion cut in taxes.

Somehow, whenever the Greens gain state power, in those years on the national level or in state-level cabinet posts, their militancy often gets diluted like over-watered coffee in a bad café.

Strong on equality for women, LGBTI rights, on opposing racism, hatred of foreigners and neo-fascists of every new brand and variety, they gained their big new increase in strength largely thanks to growing awareness by millions of the rapid destruction of our environment, felt clearly in rising temperatures, droughts and floods. Their sins in federal cabinets were largely forgotten after 2005; indeed, a major plus point is currently their simple absence from any wimpy federal government.

But it’s better not to look too closely at their actions on state levels. After fighting long and conspicuously against further extending the huge Frankfurt airport – “Save our environment!” – they made the then unusual decision to join in a state government with the right-wing Christian Democratic Union (CDU). When their leader became deputy minister president and economics minister, they somehow forgot opposition and approved the extension (though the Herr Minister himself was somehow unable to attend its fancy opening ceremony, with or without sneakers and a wool sweater.

A year ago a majority of Germans, with the Greens among the loudest, celebrated the decision to save the ancient Hambacher Forest between Cologne and Aachen after its passionate defense by countless demonstrators, with some holding out in tree huts. Rarely mentioned was the fact that five years earlier, when the Greens shared coalition posts with the Social Democrats ruling the state of North-Rhine-Westphalia, their three cabinet ministers had all approved cutting down the forest in favor of open pit lignite coal digging.

Another example is from northern Schleswig-Holstein. While handsome Green national co-chair Robert Habeck loudly calls for capping rent levels – an urgent demand now heard on many sides – the three-party coalition up there, with the CDU and the Greens and the openly pro-capitalist Free German Party (FDP), quietly lifted the existing state lid on rent increases. Again the Greens bowed to their “Christian” partner.

In the state of Baden-Wurttemberg in southwest Germany the Greens also joined in a coalition with the CDU-rightists, but this time, in the first and only case thus far in Germany, as head of a state government. But here, too. their somehow still popular, tall, scratchy-voiced Minister President Winfried Kretschmann seemed to overlook his Green roots. His roots searched richer soil; the giant Daimler-Benz maker of Mercedes cars is centered near his capital, Stuttgart. As he has often made clear, he knows which fertilizer is most advantageous. For years his special sleek green Mercedes government vehicle was famous for its 441 horse power. “I am very big and I need to travel quickly” he explained. (But a critical journalist asked if he really needed a speed of up to 150 mph.)

When even greater speed is necessary, he flies. Dismissing the highly-publicized demands of Robert Habeck for an ecological ban on domestic flights in Germany he said: “I don’t think much of all that moralizing … We shouldn’t dictate people’s style of life.” That also seems to apply when Daimler, like Volkswagen, BMW and the others go in for a bit of leaded exhaust pipe trickery.

The Greens have been finding it ever easier to abandon earlier inhibitions about teaming up with the right-wing Christian CDU – and making all kinds of compromises while doing so.

In this way, they seem to be replacing the Social Democrats, who have long been doing the same thing – and thus moving currently to the brink of disaster; their membership has halved, their status in national polls is now at 13 percent. This has forced them into an almost desperate hunt for new leaders; about a dozen male-female duos now choke the field of candidates, somewhat like US presidential campaigns. It is also forcing them to add an almost forgotten left-sounding timbre to their voices, at least when elections approach.

The Greens also speak in progressive tones – and still take some positions in that direction. Maybe a fitting symbol for them would be some kind of mixed bag, some contents generally attractive, others attractive only as coalition partners for the CDU, for unlike the Social Democrats they have almost no complicating ties to the union movement, hence must make no traditional bows in that direction. The Green membership was largely based on once rebellious collegians, most of whom are now highly educated, upper middle-class professionals. It is not yet clear if this base is now broadening.

When it comes to foreign policy, they are more Russophobic than any other party, always from a purely humanitarian standpoint, of course, like some American politicians on both sides of the aisle. While the Social Democrats sometimes lean here and there towards diplomacy in a world threatened constantly by the menace of atomic war, the Greens lean all too often toward confrontation.

But the Greens are not a monolithic bunch. Some members and some local groups still recall progressive trends from their past – and not exclusively restricted to well-spoken words.

The three states in Eastern Germany now facing elections (two of them on Sunday) will be forced to decide on coalitions; no party will be strong enough to rule alone, most likely not even in two-party tandems. In both Thuringia (due to vote in October) and Berlin, the Greens, Social Democrats and the LINKE (Left) have long since combined to get a majority of seatsand form the government. This will very likely happen now in Brandenburg; in Saxony it may even be necessary for those three to accept the CDU as boss in a four-way attempt – if only to keep the fascistic Alternative for Germany (AfD) out of office. With German politics ever more chaotic, the elections and weeks that follow will be of critical importance. Millions are waiting with bated breath!

+++

And again I want to mention that my book “A Socialist Defector: From Harvard to Karl-Marx-Allee” with descriptions, reflections, conclusions, plus many anecdotes and some jokes, is now available. If any of you have read it – and liked it – perhaps you can tell that to your addressees. If you didn’t like it – then, instead, tell me!

The origins of radical antifascism

The strategy of Antifascist Action can only be understood in the context of the policy of the German Communist Party (KPD) at the time, which in turn was framed by Stalinism. With the rise of Stalin in the USSR during the 1920s and the liquidation of what remained of the 1917 Russian revolution, the communist parties of the world turned into instruments of Soviet foreign policy.

For some time following 1928 (while they were completing the counter revolution inside the USSR), it suited the new Russian leaders to use very radical ultraleft rhetoric, in what was known as the “third period”. According to this position, all of Europe was in the hands of fascism. It is true that Italy was controlled by Mussolini’s fascists, but in Germany the establishment parties — the Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats — were still in charge. This was no problem for the Stalinist theory; they were simply branded as fascists and in the case of the German Social Democratic Party, the SPD, as “social fascists”. (See Rosenhaft 1983, pp28ff.).

So during the rise of Hitler the KPD, in general, fought against the Nazis, but always from the viewpoint that the SPD was an enemy as or more dangerous than the fascists themselves.

According to Poulantzas: “there seems to have formed a ‘current of opposition’ [within the KPD] in 1931… which advocated both a stronger fight against Nazism… and that the main blow be struck not against social democracy but against Nazism. However, nothing was done” (Poulantzas 1970, p216).

In 1932, the KPD group in the regional parliament of Baden presented a bill to ban the Iron Front and the Reichsbanner, the Social Democratic Party’s combat organisations (Poulantzas 1970, p210. The KPD central leadership condemned the proposal). Needless to say, the occasional calls the communists made to the SPD rank and file to join the KPD’s anti-fascist struggle didn’t sound convincing.

At times the KPD came worryingly close to the Nazis. In the Land, or region, of Prussia, in summer 1931 the Nazis began a campaign to overthrow, through a referendum, the SPD’s regional government. Initially the KPD refused to support them, but after the intervention of Moscow, the party supported the fascist campaign (Gluckstein 1999, p114, Poulantzas 1970, p213).

In November 1931 the KPD newspaper published an open letter to the “fellow workers” of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) and the stormtroopers, declaring that “as honest fighters against the hunger system, the proletarian supporters of the NSDAP have joined the United Front of the proletariat and carried out their revolutionary duty” (Rote Fahne, 1 November 1931, cited in Gluckstein 1999, pp113-114). On 18 May 1932 —exactly the period in which the Antifa movement was being prepared— the KPD organised a public meeting with the participation of a Nazi speaker and three hundred NSDAP supporters. (Rote Fahne, 20 May 1932, cited in Gluckstein 1999, p113).

In November 1932 — just months before Hitler’s takeover, and months after the creation of Antifa — both the KPD and the Nazi trade union, the NSBO, celebrated their collaboration —their “united front”— in organising a wildcat transport strike in Berlin. (Gluckstein 1999, p116).

Already in the 1920s, the KPD had had a combat force called Rotfrontkämpferbund or “League of the Red Front Fighters.” Officially banned in 1929, in fact the organisation continued to function. However, in order to act more openly, the KPD announced in its press, in May 1932, the launching of Antifaschistische Aktion, Antifascist Action. The inaugural event — of which there is a famous photo, of a huge hall decorated with the anti-fascist red flag — was held in June 1932.

Initially some KPD leaders wanted the Antifa movement to be more than just a front for the party. There was talk of a possible understanding with the socialists, and in the photo of the founding congress you can see a socialist banner. But this open attitude didn’t last long.

Under pressure from Moscow, the KPD leadership quickly made it clear that Antifa would oppose not only the Nazis but also the SPD: “Anti-Fascist Action means untiring daily exposure of the shameless, treacherous role of the SPD and ADGB [socialist trade union] leaders who are the direct filthy helpers of fascism” (Rote Fahne, 1 July 1932, quoted in Gluckstein 1999, p115).

As it had been doing since 1929, with the Antifa movement the KPD insisted that in order to fight against fascism it was necessary to fight against capitalism. A pact with the SPD was, therefore, unthinkable. Faced with some attempts to create unity from below, the KPD leader, Thälmann, warned in September 1932 against “dangerous conceptions such as ‘unity above the heads of all the leaders’… Such tendencies can bring the greatest damage” (Poulantzas 1970, p212).

In January 1933, just over half a year after the creation of Antifa, Hitler came to power. The KPD leaders, faithful to their “theory of the third period”, gave this fact little importance, insisting that he would not last long and that “After Hitler, we will take over!” (Wilde 2013). Despite all the KPD’s revolutionary rhetoric, and its hundreds of thousands of members, the Nazis took control of Germany almost unopposed.

It must be said that the SPD was not any better. The Social Democratic leaders accused the Communists of being “Red Nazis”, comparable to Hitler’s followers. The best response to fascism, they insisted, was defending the Constitution and the rule of law. To fight against the Nazis, as the communists did, was to lower themselves to their level. And more things in the same vein. In short, the policy of the SPD against Hitler was also disastrous.

There was an alternative. The Russian revolutionary, Trotsky, defended the policy of the united front; an alliance of all left wing organisations — especially the KPD and the SPD — against the Nazis, without hiding the political differences.

In September 1930, for example, he wrote: “What will the Communist Party ‘defend’? The Weimar Constitution? No,… [the] Communist Party must call for the defence of those material and moral positions which the working class has managed to win in the German state. This most directly concerns the fate of the workers’ political organizations, trade unions, newspapers, printing plants, clubs, libraries, etc. Communist workers must say to their Social Democratic counterparts: ‘The policies of our parties are irreconcilably opposed; but if the fascists come tonight to wreck your organization’s hall, we will come running, arms in hand, to help you. Will you promise us that if our organization is threatened you will rush to our aid?’ This is the quintessence of our policy in the present period.” (Trotsky 1930). He continued to insist on this vision until the victory of Hitler. (See also, for example, Trotsky 1931 and Trotsky 1933).

Trotsky had very few followers in Germany but still they tried to put their policy into practice. One of them, Oscar Hippe, recounted the experience later.

During 1931 the Trotskyists in Germany called on the other workers’ parties to push for a united struggle against the Nazis. They specially called on the KPD to help create action committees against fascism with the participation of all the workers’ parties, unions, factory committees, etc. If they were created, these committees should be united through a founding congress to establish a movement throughout the country.

They did not just make statements; where they had a real base, they fought to build united movements against fascism. In Oranienburg, a city near Berlin, much of the local KPD had gone over to the Trotskyists, and Committees for the United Front were established. Their rallies in different neighbourhoods of Oranienburg attracted some six hundred people. Different sectors of the left participated in these committees, including KPD activists, and in some neighbourhoods the SPD as a party.

Hippe adds, however, that “the KPD always tried to break up the committees”. It is interesting that the experience of the united struggle against fascism fostered unity in other areas. A unitary unemployed workers’ movement was established in Oranienburg, which led a demonstration of 2,000 people to the town hall. The leadership of the KPD did everything possible to sabotage the unitary model. In Berlin, they mobilized the communist youth — activists who probably also belonged to the Antifa movement — to attack with clubs and stones those activists who put up posters or painted slogans in favour of the united front against fascism. (Hippe 1991, pp128-132).

In the end, neither Trotsky’s warnings nor his followers’ attempts to put their strategy into practice managed to break the resistance of the two big parties, except in isolated cases such as those described above. Hippe explains that at the beginning of 1933, “The desire for unity existed among large parts of the working class; only the leaders of the two workers’ parties worked against it. The KPD did not want to back down from its theory of social fascism, while the leaders of the SPD played down the dangers and based themselves on parliamentary activity. We went into 1933 in the knowledge that the victory of Fascism could no longer be prevented. In the final four weeks, our activities increased in spite of everything… “(Hippe 1991, p136).

To complete the picture of the lack of principles of the Stalinist leaders who had promoted the strategy of Antifascist Action, we must remember what they did over the following years. After the terrible defeat represented by the destruction of the German working class— the strongest in Europe — in 1933, the foreign policy of the USSR made a 180-degree turn. In 1934, Moscow began to promote the politics of the popular front. Only two years after helping divide the German working class because of their differences with the Social Democrats, now the communist parties had to ally with “the progressive bourgeoisie”.

In 1935, Stalin signed a military pact with France, then still one of the world’s leading imperialist powers. Pierre Laval signed the deal on behalf of the right-wing government of France. Months before, Laval had met and come to an agreement with Mussolini, giving the green light to the imperialist ambitions of fascist Italy in Africa. Far from insisting on opposition to capitalism as a precondition, with the popular fronts the communist parties repressed those sectors of the left and of the working class that wanted to break with capitalism — all in the name of maintaining “unity”. The central objective of this policy was a broader pact, which was not achieved at that time, between Stalin’s USSR and the imperialist bourgeoisies of Great Britain and France.

When this strategy failed, Stalin did another about turn in 1939 and came to an agreement with Hitler. Again, one assumes that he did not demand that the Nazi leader reject capitalism.

The disastrous failure of the anti-fascist action strategy should serve as a warning to activists who want to stop fascism today. Sadly, in general, that is not the case. In a future article we will look at how sectors of the current antifascist movement repeat many of the mistakes of the past, running the risk of repeating the same tragic end.

I just discovered an article entitled “For the organisation of the Anti-Fascist United Front in the Workplaces”, in the Euskadi Roja(newspaper in Euskadi of the Communist Party of Spain), 23 December 1933. Eleven months after Hitler took power, they continued to reproduce the tragic errors of the Antifa strategy.

The call starts well:

The European Anti-Fascist Workers’ Congress decided to elect a Central Committee of Workers’ Antifascist Unity of Europe [whose tasks include]:

3. Intensify the efforts to constitute the broadest antifascist front of all workers, employees, petty bourgeois, poor peasants and intellectuals in the fight against fascism and imperialist war.

The creation of the broadest front of struggle of all anti-fascists, without distinction of party, union tendencies or religion, of all those who are ready to unite to annihilate fascism…

The problem is that this apparent desire for unity was not real. A few lines later we read that they propose:

5. A determined fight against all saboteurs of the antifascist united front and tirelessly denounce the support provided by the Second International and the reformist trade union leaders who have paved the way for Hitler, Mussolini, Pilsudksi, etc., who have sabotaged the anti-fascist struggle and who aim to continue to lend their support to fascism.

That is to say, just as in Germany in 1932, they were proposing a united struggle “without party distinction”… on the basis of denouncing the social democrat party. As we have seen, a few months later, Moscow began to turn towards the strategy of the popular front, of pacts (without conditions or denunciations) with the “progressive bourgeoisies”.

This article originally appeared in David Karvala’s Spanish-language book El Antifascismo del 99%. The chapter explores the origins of “antifa” (an abbreviation of the German name “Antifaschistische Aktion”), which was an organization of the German Communist Party in the 1930s. Reproduced with permission

Gluckstein, Donny (1999), The Nazis, capitalism and the working class, Bookmarks, London.

Hippe, Oscar (1991), …and red is the colour of our flag, Index, London.

Karvala, David (2012), “La larga sombra del estalinismo”.

Poulantzas, Nicos (1970), Fascismo y dictadura: La tercera internacional frente al fascismo [There seems to be no online version in English]

Rosenhaft, Eve (1983), Beating the Fascists?: The German Communists and Political Violence, 1929-1933. Cambridge University Press.

Trotsky, Leon (1930), “The Turn in the Communist International and the Situation in Germany”, 26 September 1930, Available at

Trotsky, Leon (1931), “The Impending Danger of Fascism in Germany: A Letter to a German Communist Worker on the United Front Against Hitler”, 8 December 1931.

Trotsky, Leon (1933), “The United Front for Defense: A Letter to a Social Democratic Worker”, 23 February 1933.

Wilde, Florian (2013), “Divided they fell: the German left and the rise of Hitler”, en International Socialism 137, winter 2013.

Photos by Phil Butland, Michael Ferschke, Doris Hammer, Julie Niederhauser, Einde O’Callaghan, Rene Paulokat, Jaime Martinez Porro and Alper Sirin

The Left Berlin

24/08/2019

Photos by Phil Butland, Michael Ferschke, Doris Hammer, Julie Niederhauser, Einde O’Callaghan, Rene Paulokat, Jaime Martinez Porro and Alper Sirin

Islamophobia is hitting the headlines again in France, as over 20 000 marched joyfully against it in Paris on Sunday, singing and chanting, backed by major trade unions and radical Left parties. Are we finally seeing a real shift in the dreadful politics of the French Left on islamophobia? A huge row about Islam and racism […]

John Mullen

11/08/2019

Islamophobia is hitting the headlines again in France, as over 20 000 marched joyfully against it in Paris on Sunday, singing and chanting, backed by major trade unions and radical Left parties. Are we finally seeing a real shift in the dreadful politics of the French Left on islamophobia?

A huge row about Islam and racism is on the front pages in France. At the end of October, a former candidate from Marine le Pen’s party (now called National Rally) attacked a mosque in Bayonne in South-West France with a revolver and an incendiary bomb, seriously wounding two Muslims. This was the third and gravest racist attack on the mosque over the last five years, and a number of other mosques have suffered arson attacks or racist graffiti.

Two weeks earlier, a fascist representative on a regional council in the centre of France demanded that a Muslim mother wearing a headscarf (who was accompanying a group of schoolchildren coming to see how democracy works) be expelled from the public gallery. Voices were raised in protest but also many in support of the expulsion. The same week, the Senate voted (163 to 114) the first reading of a bill to ban mothers wearing headscarves from accompanying school trips. Although the bill will no doubt fall at a later parliamentary stage, it is a terrible symbol of the hatred faced by Muslims in France. A mainstream right-wing senator compared women wearing headscarves to “Hallowe’en witches”; he claimed that the women were not simply living their religion, but were “communitarianists” threatening the spirit of the Republic. A group of intellectuals published an appeal in Le Figaro newspaper in favour of banning Muslims wearing headscarves from school trips. The Education minister, Jean-Michel Blanquer, declared that the headscarf should not be banned, but “is not wanted in our society”. Early November, in a nursery school which had organized workshops about “respecting other people”, involving the children’s parents, the regional Education Chief, due for an official visit, refused to enter the premises because there were three Muslim mothers with headscarves. In a recent poll, 42% of Muslims said they had faced discrimination on account of their religion. For those with higher education diplomas, the percentage was far higher (as long as -mostly Arab – Muslims stay « in their place » as cleaners or security guards, they do not get targetted as much).

The shocking blind spot of the French Left

For twenty years, islamophobia has regularly been used to divide in France, more so than in other countries, because the Left has been so criminally weak on the issue. A tradition on the Left of despising believers, which goes back many decades, merged with lingering neo-colonialist attitudes and the new international Islamophobic priorities since 2001, to give rise to an unconsciously racist consensus which has gangrened the Left. It is still not unusual to find activists who have spent decades fighting for refugee rights or combatting other forms of racism who have horribly backward ideas about Muslims, and in particular refuse to really imagine that one might be French and Muslim (so any discussion of Islam turns within seconds to comments about Saudi Arabia). Older readers can compare the situation to the way genuinely Left people could be horribly homophobic, fifty years ago.

In 2004, the law which banned headscarves among high-school students encountered no serious opposition from the radical Left: demonstrations gathered a few dozen people only. Even the mainstream of the revolutionary Left (at the time the Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire), which had had better positions ten years earlier, ran a front page “Neither this law nor the veil!”, abandoning its duty to defend oppressed groups. Most of the Left supported the ban, and some far-Left activists ran campaigns locally to extend the ban to parts of universities, while their organizations, deeply divided, did not stop them. The 2010 follow-up law, which forbade the wearing of a niqab in any public space, saw even less opposition. This law was historic in that it was the first time a law had been passed to ban a practice followed by a tiny minority: its real motivation was to please racist voters by underlining “the problem” cause by Muslims.

In 2010, when a local group of the New Anticapitalist Party chose, as a candidate for municipal elections, a young Muslim woman who wore a headscarf, the highly emotional national conference was divided almost exactly fifty/fifty on the issue, and the young woman soon left the party. In 2016, when some right-wing mayors banned full-body swimsuits on beaches, there were some press releases from the radical Left in protest, and one small demonstration on a beach. But year after year, there have been no public meetings, no campaigns, pamphlets, books or demonstrations set up by Left parties against islamophobia, even though this form of racism is the one which is most helping to build the fascist National Rally in the country (its polls are presently around 23% of voting intention).

The result of this weakness was a heaven-sent gift to Macron and to the Right in general. Since attacking Muslims would not give rise to any concerted opposition from the Left, it was the ideal tactic for any government pushing through austerity packages who wanted to put up a smoke screen. Macron’s modernist branch of the Right has not traditionally been the one the most involved with pointing the finger at Muslims, but as his position becomes more and more precarious, what with the continuing Yellow Vest movement, electoral pressure from the far right, and upcoming mass strikes to defend pensions, islamophobia is an irresistible tactic for him, too.

Fighting islamophobia at last

The attitude of Left organizations is slowly and painfully beginning to change. On Sunday 10 November, over 20 000 marched in Paris, backed by the biggest national union confederation, the CGT, as well as the smaller, more radical confederation SUD, by the France Insoumise (biggest of the left reformist movements, a sort of French Corbynism), and by the Communist Party. The call was launched by Madjid Messaoudene, a Left city councillor in Saint Denis and taken up by Muslim organizations, students’ unions and the New Anticapitalist Party before gaining wider support. Yellow Vest leaders and Human Rights organizations also marched. To my surprise, my local baker’s in the Paris suburbs had a pile of leaflets on his counter about the demonstration (whereas local Muslims have been more used to keeping their heads down than fighting back).

The march drew many thousands of Muslim women in headscarves, their faces showing joy and disbelief as crowds chanted “If you like being with Muslims, clap your hands!” and “Solidarity with veiled women!” The Yellow Vest signature song was adapted and sung en masse “Here we are, here we are, even if Blanquer doesn’t want it, here we are! For the honour of the Muslims, for respect for our mothers, even if Blanquer doesn’t want it, here we are!” French tricolour flags were waved and many home-made placards announced “We are proud of being French AND Muslim!” Other slogans included “We’re in danger, we’re not dangerous!”, “Criticizing religion: yes! Hating believers: No!” and “Muslims aren’t the problem: islamophobes are full of hate!”

Older activists against islamophobia like myself were deeply moved: we have been waiting for this for twenty-five years. This change on the Left is due to a number of factors, in addition to the escalation of attacks on Muslims to the latest shooting, the violence of which has shocked many who had reacted little to less violent attacks. Firstly, non-white organizations, including many Muslim women, organizing against police racism in particular, but also against islamophobia, have built, over recent years, small but dynamic independent campaigning networks, which are able to get a few thousand out demonstrating. As was the case in the past with gays and with women, the oppressed mobilizing independently of the Left are teaching Left activists to improve their politics.

Secondly, inside each radical or revolutionary Left organization, the small minority that understands the importance of actively fighting islamophobia has been plugging away for twenty years and is now considerably larger (though still a minority in every organization).

Thirdly, there is a generational change. The older anti-religious campaigners, whether in feminist circles, in teaching trade unions or in radical or revolutionary Left parties are, happily, not managing to convince younger generations of activists, who have been immersed in multicultural communities since school days and do not see why their Muslim contemporaries should not be treated like everyone else, rather than ostracized as if they possessed Black Magic powers.

Sunday’s demonstration has brought the row into the mass media. Blanquer, Macron’s education minister, spoke of “a deplorable initiative” opposed to the principles of a secular state. The (ever more Blairite) Socialist Party refused to join the march. Some of them have called for an alternative rally the following Sunday “For secularism and against racism”. Left wing politicians (including a couple of those who signed the call to demonstrate) have been searching through the list of 400 initial signatories to find someone who is too reactionary about some question or other, so as to have an excuse to distance themselves the march. One humorous cartoon going the rounds showed a left-wing activist being asked “Are you going to the march against islamophobia?” He looks unsure and asks in a worried tone “I don’t know – there won’t be Muslims there, will there?”

There will be a fierce backlash by the Islamophobic sections of the Left and the Right, who are both fairly well-organized. There is even a popular weekly magazine, Marianne for secularist islamophobes who think they are on the Left. In every Left organization or trade union which supported the demonstration, there are large numbers who boycotted it. Very few trade unions indeed brought their banners on the march. These people need to be persuaded. Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen is hoping to polarize around the march, claiming that everyone supporting it is playing into the hands of Islamic fundamentalism and accusing la France Insoumise of being in reality “la France islamiste”. Macron’s ministers are doing the rounds of television studios explaining how “foolish and naïve” the Left is being.

But at least the fight is on. The march is an enormous step forward. The front page of the Paris local newspaper last week read “Muslims faced with racism”, whereas even vicious attacks in the past had only given rise to local demonstrations of a couple of hundred Muslims and always the same twenty or so of us activists from various Left organizations.

Some Muslim activists are understandably sceptical, and are claiming that the upcoming municipal elections are the reason behind the mobilization of politicians looking for votes. This is unlikely – the terrible truth on the Left in France is that an organization is more likely to lose votes by supporting Muslims than gain them. A poll published last week showed that two thirds of French citizens think that mothers wearing headscarves should be banned from accompanying school trips! There is an urgent need for a broad campaign against islamophobia.

Jean- Luc Mélenchon, leader of the parliamentary group of France Insoumise MPs, a group of 17 MPs a few of whom are clearly unhappy about this march, has nailed his colours to the mast (whereas previously even his verbal opposition to islamophobia had frequently been ambiguous). There will certainly be resignations from the France Insoumise because of this demonstration (the grouping integrated left currents characterized by hardline secularism), so it was very heartening to see Mélenchon standing firm. “When our Muslim fellow countrymen, representing the second largest religion in France, are stigmatized, insulted and physically threatened, it is our duty to come to their aid” he said. In addition, the front page of the weekly newspaper of the New Anticapitalist Party called for people to join the demonstration. Even the Trotskyist organization Lutte Ouvrière (which has in the past enthusiastically supported laws against Muslim headwear) attended.

If this fightback can be sustained, it could remove from Macron’s hands a powerful divisive weapon. As unions in transport, education and health gear up for massive strikes from 5th December on, unity against racism and islamophobia can be a big boost for our class. The class anger, amid rising poverty (9.3 million below the poverty line), must take centre stage, not racist division disguised as the defence of secular civilization.