As of the beginning of August, President Emmanuel Macron has let at least 112 000 people die of Covid in France, and there are still a thousand Covid patients in intensive care today. At every point, the interests of profit have been his priority. We have seen half-hearted lockdowns, called too late and lifted too soon, with much too little financial help for workers to make sure they could respect the rules, and criminally low investment in vaccination programmes, which started late and advanced slowly. Most of the deaths could have been avoided, and this, added to the neoliberal dismantling of the health service over the past years, means there are plenty of reasons to be angry with Macron and with capitalism. But left organizations here have a responsibility, too, and have been making dangerous concessions to vaccine skepticism which will help the far-right to build up more of a following.

In many countries, demonstrations against lockdowns or vaccines have been clearly far-right enterprises, but in France a vigorous row divides left activists. The last three Saturdays in July saw demonstrations in over 185 towns against the “health pass” announced by Macron. This pass proves you have been vaccinated, tested very recently, or have recovered from Covid, and it will be compulsory from mid-August to get onto long-distance trains, or into cinemas, restaurants, football matches, concerts and so on. On many of the demonstrations, slogans calling for Macron’s resignation were prominent.

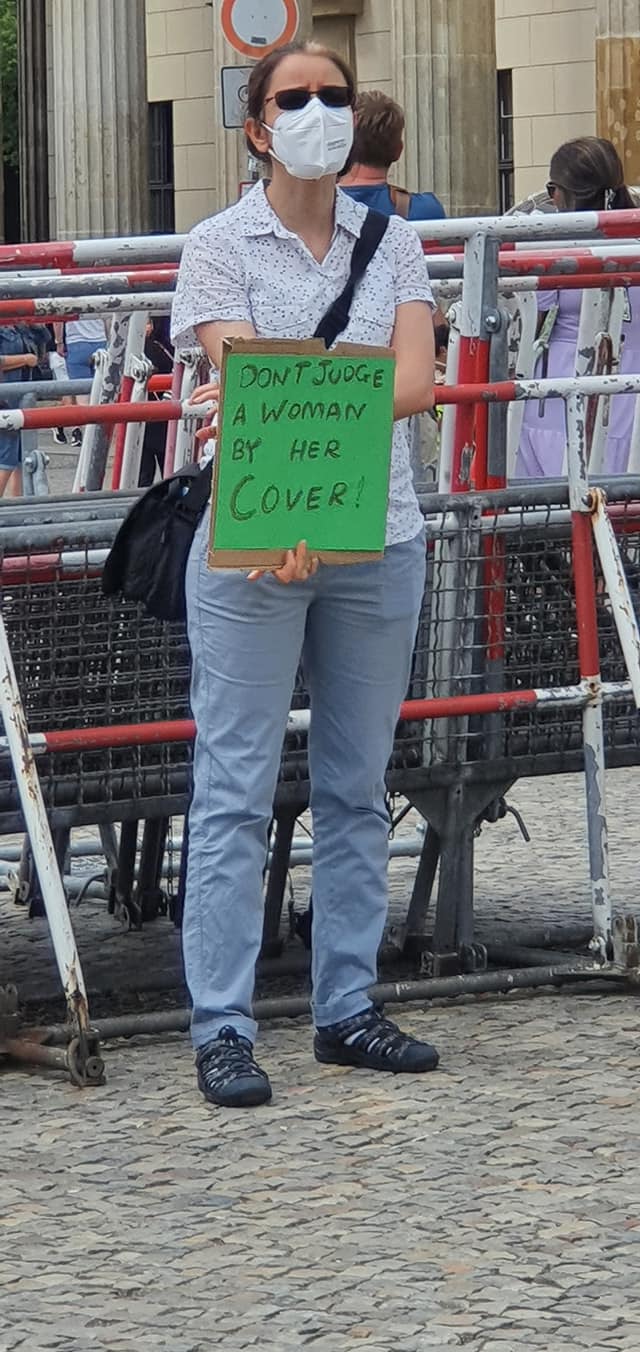

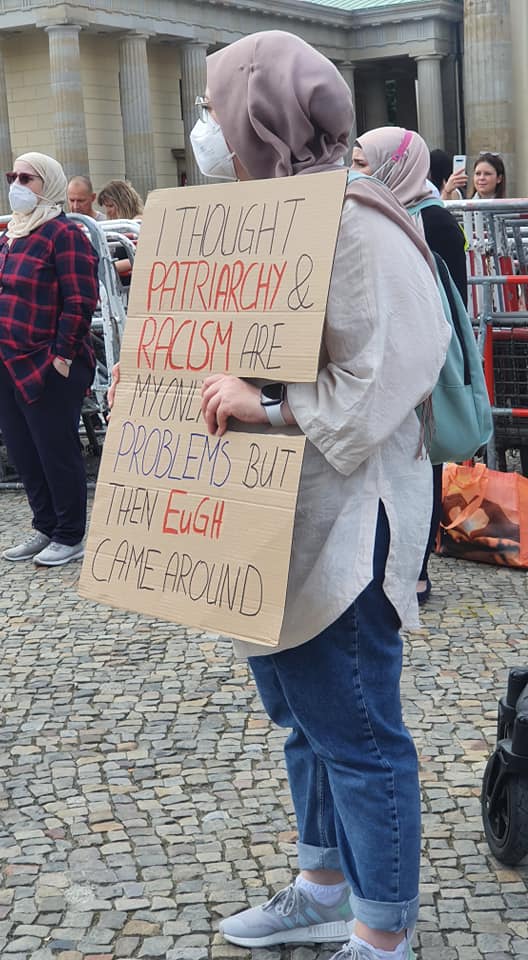

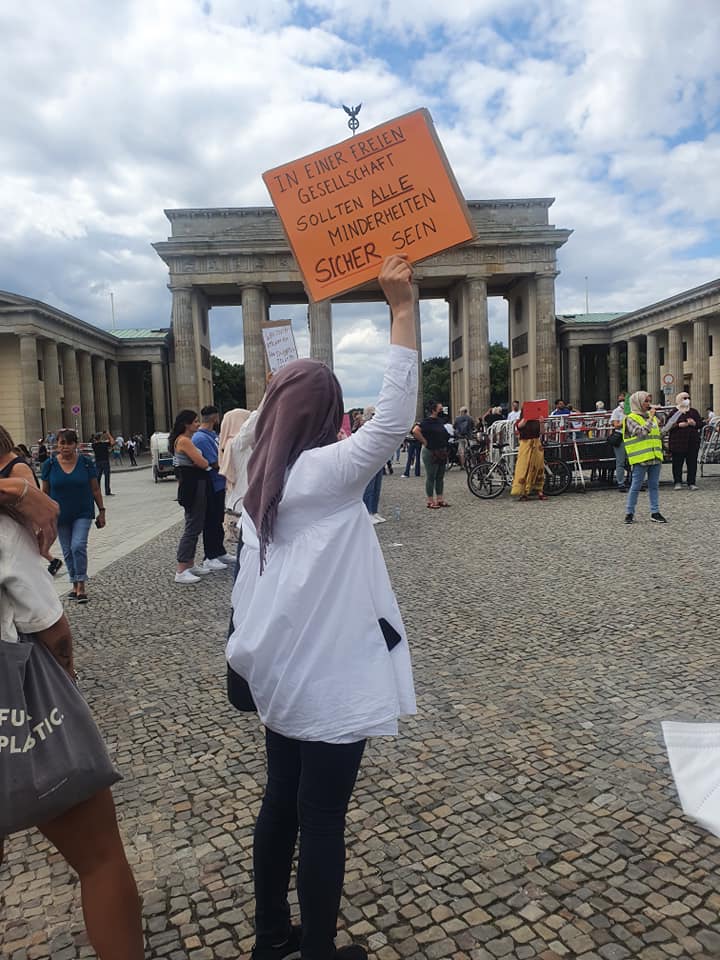

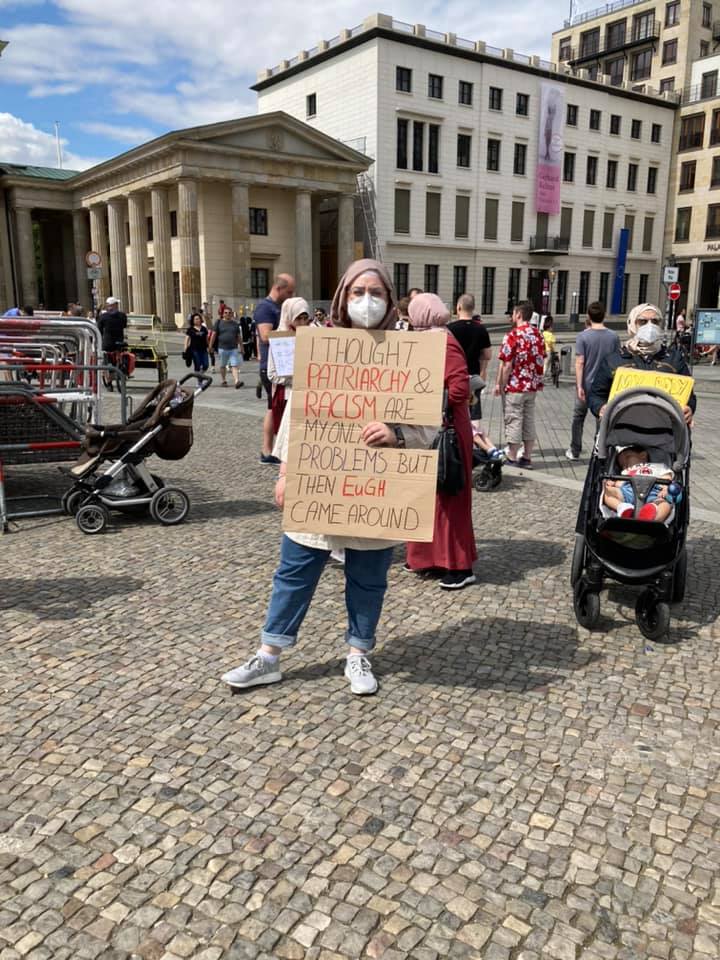

Demonstrators were counted at anything up to 250 000 people on July 24, and at least as many the following week. There were no trade union banners, and the people present came from all parts of the political spectrum, most no doubt thinking it was not a question of being right or left wing. Political organizations were generally not visible, most placards were home made, and consensual chants of “liberté” were the most common slogan. When activists were seen, they were generally from the far-right or from the radical left. In Paris there were separate marches on July 24 and 31, one led by fascist Florian Philippot, behind a banner “Vaccinated and unvaccinated united!”, the other organized by Yellow Vest activists from the non-party movement which humiliated Macron so often in 2018- 2020.

But in most towns there was only one march, which may or may not have included fascists. In Orléans and in Bordeaux, far-right royalists openly joined the demonstration. In Poitiers on the 31st there was both an antifascist flag and a far-right royalist one, as well as NPA (New Anticapitalist Party) newspaper sellers. Yet on the main banner in Toulouse the slogan denounced both the health pass and the attacks on retirement pensions.

Placards against vaccines were regularly seen (“We don’t want to be guinea pigs”, “Against sanitary dictatorship”, “Hands off my DNA!”, or “My body, my choice”). But there were also placards accusing Macron of being a Nazi, slogans such as “No Pass, no pasaran” and even a few yellow stars with the word “unvaccinated” written on them, a disgusting attempt to compare the fate of unvaccinated people today with that of French Jews in the Holocaust. Such symbols were denounced by all left organizations, but a poll showed that over half of those expressing strong support for these demos were “not shocked” by them.

Authoritarianism

Macron announced his measures on July 12, in a long speech in which he also pitched his bid to be re-elected as president in 2022. The new law also makes vaccination a condition of employment for health and care workers. Macron’s aim is to facilitate opening up the profit economy as quickly as he can, no doubt too quickly.

After the pandemic, many left-wingers have been waiting for an explosion of mass anger, but this has come in an unexpected form, with much confusion. Should we oppose the principle of the health pass? And should we participate in demonstrations even where the main tone of the rally is anti-vaccine, and the far-right is supporting? And what about compulsory vaccination for health workers and care home workers?

Many on the left denounce the health pass as a dangerous further move towards authoritarianism. Others insist that unity between those who choose to be vaccinated and those who choose not to be is essential in order to oppose this dangerous attack on individual freedom. The 17 radical left France Insoumise Members of Parliament claimed on July 24 that the health pass was “absurd, unfair and authoritarian” and was a step on the road to a society of “generalized surveillance”. For the FI this extreme measure was meant to compensate for the incompetent management of the crisis by Macron’s government and the criminal under-funding of the health service over decades of neoliberalism. Compulsory vaccination of sections of the workforce was said to be a “violent” measure “undermining freedom”. FI members of parliament have organized a challenge to the new law in the courts, and the verdict is expected early August.

Some local FI groups have been joining the recent demonstrations, others not. Mélenchon did not directly call his supporters to participate, but said that the demonstration “should be listened to”. He also asked supporters demonstrating to distance themselves from the “excessive” slogans sometimes seen. “No, a freely chosen vaccine is not apartheid, a vaccination campaign is not a Holocaust”, he said.

A wider alliance of radical left figures organized by social justice campaign ATTAC, and including national leaders of most union federations and left parties, set up a petition on the 28 of July. It declares that while “a massive vaccination campaign is necessary to fight this pandemic”, the health pass and compulsory vaccination measures are “undemocratic and harmful”. The petition also denounces neoliberal attacks on pensioners and on the unemployed, as well as calls for the lifting of patents on vaccines. Another group, comprised of 200 lawyers, signed a declaration stating “We are neither in favour of vaccines nor against them, but we want freedoms to be respected”.

Similar arguments were put forward by the New Anticapitalist Party, defending the idea of mass vaccination but opposing the health pass and any sanctions against unvaccinated health or care workers. The NPA leaflet from the 28 of July called, perhaps a little timidly, to “defend these ideas, including by joining in mobilizations everywhere where it is possible to popularize such policies”.

The other main Trotskyist organization, Lutte Ouvrière, seemed to go even further in making concessions to anti-vaccine feeling. Their weekly workplaces leaflet declared “ Yes, vaccination could be a step forward if capitalism was not concerned with profit rather than the satisfaction of human needs”.

Only one significant left organization, Ensemble, openly declared it was not joining the demonstrations. The FI and the NPA left the decision to local sections, usually depending on how prominent the far-right elements were in local rallies. And indeed, on the 31st, the NPA joined the demos in some towns, such as Poitiers and Bordeaux , and refused to do so in others such as Bourges.

Vaccine skepticism

Being against the vaccine is contrary to the interests of workers, who account for the vast majority of deaths. Yet skepticism about vaccines is very strong on the left in France. Last January, a poll showed that only 59% of those identifying as left-wing intended to get vaccinated (as against 69% of right-wingers). Only 36% of supporters of the radical left France Insoumise wanted to!

Reluctance has been somewhat reduced since, but skepticism remains high in the country. It is particularly high among non-white populations, who are, understandably, used to mistrusting a racist state. In the French overseas departments of Guadeloupe and Martinique, vaccination rates are half those of the metropole. Stéphanie Mulot, a sociologist, explained “there is much mistrust of the French government … refusing the vaccine is an oppositional political position”. In professions where individualism is particularly prized, skepticism is also high: artists, theatre, and cinema workers as well as musicians are often particularly vocal in the demonstrations. With few exceptions, left leaders have done little or nothing to challenge vaccine skepticism among their supporters, and are today making mistaken concessions to anti-vaccine sentiment.

No concessions to anti-vaccine ideas

A recent opinion poll showed 35% of French people “felt sympathy” for the demonstrations against the health pass, while 49% were opposed and 16% indifferent. The survey showed that 46% of working-class people felt sympathy and 31% clearly supported the mobilization. Unsurprisingly, given their individualist orientation, 61% of business owners felt sympathy too. Sympathy was expressed by 38% of left voters, 24% of right-wing voters, 49% of far-right voters and 50% of those who voted France Insoumise. However, the situation is complex, since another recent poll showed 69% of citizens thought unvaccinated people should not be allowed to work in health or in care homes (60% of working-class respondents in employment , 87% of retired people) and 62% are in favour of the COVID passport (a little over 50% of working class respondents in employment, 81% of retired).

This poses two urgent questions: Firstly, can these demonstrations expressing anger against Macron be pushed in a leftward direction? And secondly, should the left oppose the health pass on principle, and the imposition of vaccination as a condition of employment? Most left organizations seem unsure about the first but sure about the second: hence the challenge to the law in court and the broadly-based petition. Left-wingers on the demonstrations insist that a mobilization intended to defend individual freedom should not be left to the right-wingers.

For my part, I think the main body of demonstrators are campaigning because they do not want to be vaccinated. Although in form the marches resemble the early Yellow Vest marches, the Yellow Vests were marching against poverty, not in favour of a (wrong) individual choice. The popularity of the protests is the sign of a move to the right. The far-right is more likely to benefit than is the left. I do not think that adding demands about pensions to your placards will change much. The left should be campaigning for people to be vaccinated, and should not be presenting vaccination as purely a matter of individual choice.

Secondly, although any law passed by Macron will of course be applied in a discriminatory and authoritarian manner, is the left correct to oppose these measures on principle? Since Macron’s announcement, in 17 days, 4.7 million people in France got their first dose of the vaccine. The rate of vaccination doubled as compared to the previous month. This acceleration will save many lives, and there is no point in denying this.

Just as for other health and safety rules, trade unions in other circumstances have campaigned for vaccination to be compulsory for working in certain sectors. In 2013, the CGT Trade Union here pushed for compulsory vaccination against leptospirosis for sewerage workers. Although there are obvious advantages to using persuasion, and Macron’s arrogance rightly makes people angry, is it a left-wing priority to mobilize against these measures? There is nothing inherently right-wing about compulsory vaccination, which was a bolshevik policy just after the Russian Revolution. Do we really want to “respect” people’s right to put others in danger?

Is a health pass different in principle to alcohol testing for drivers or eyesight tests for bus drivers? And, in a world where my mobile phone, my credit card and CCTV cameras would allow state agencies to know huge amounts about me, if I were important enough to care about, it is not clear that the pass is a decisive step towards 1984.

Universal vaccination is absolutely in the interests of the working class. An impatience to see masses back on the streets has led much of the left to downplay the centrality of vaccination and make concessions to anti-scientific nonsense. This, sadly, will help the far right to build. This month’s demonstrations in Paris were the biggest ones addressed by fascist leaders for many years, and they faced no opposition on the streets. Last week, two vaccination centres were vandalized, and in Montpellier this week a COVID testing tent was attacked. A far right which has long had difficulty getting thousands on the streets is making the most of the situation.

We need rather a campaign for vaccination, and quality health care, for the whole of the world’s population.