According to the Ocalenie Foundation, an organization which provides assistance to refugees, 32 refugees are trapped on the Polish border with Belarus, close to Usnarz Górny. They include women and a 15 year old girl.

The refugees can’t move forward and they can’t go back. They are trapped on the border surrounded by the Polish military on one side, and Belarusian soldiers on the other. The standoff has been going on for about 20 days already, and they say that they have no water or food. Images show them soaked by the rain and freezing. One of the women is complaining about difficulties breathing and pain in the kidneys. Her condition is critical. It is not exactly clear what’s wrong with her, because no medical workers are present. There has been no help, either from the Polish side or from Belarus.

The Ocalenie Foundation also reports that the health of other refugees is also deteriorating: 25 people are ill, 12 of them seriously. Yet potential help is just a few hundred metres away. For weeks activists have been trying to organize support and to provide food, water and necessities to the group of trapped refugees, but the border guards are actively preventing contact. Belarusian authorities have closed the country’s borders to prevent the refugees from returning. Poland is arguing that the refugees are currently on Belarusian territory, meaning they should apply for asylum in that country.

The situation all over the Eastern EU-border is tense and inhumane. According to activists’ reports, illegal push-backs from Poland to Belarus are happening on a regular basis. These are the actions of state services which prevent migrants from applying for international protection by forcing them to return to Belarus after crossing the Polish border, even when they declare their will for protection. The actions of the border guards are violating both human rights and the Polish Constitution and are exposing refugees to unnecessary danger.

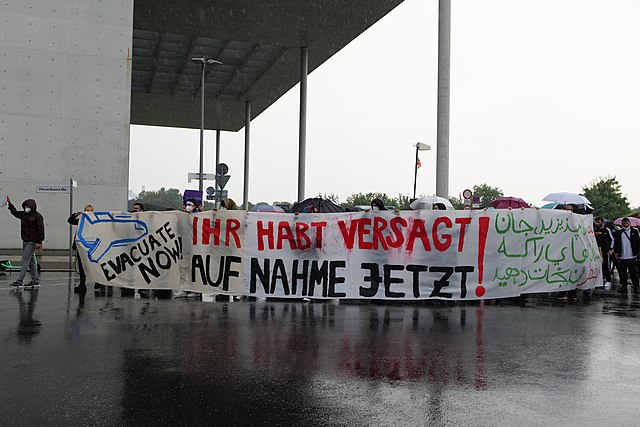

The violations by the Polish border guards, who are commissioned by the Defence Ministry, have caused great indignation in Poland. Protests demanding that the refugees are welcome have taken place all over the country and are supported by the left parties. Demonstrators hold posters and banners with slogans saying: “Border of Shame”, “Enough cruelty!”, “Enough of the policy of torture and humiliation!”, “No human is illegal”, “We do not want Polish borders of death”, “Decency is more important than order”, “Accept Refugees, kick out the Nazis.”

There are fundraising campaigns to help collect food, water, clothes, tents, sleeping bags, and money for legal aid. The MEP of the left party Razem, Maciej Konieczny, was admitted by the border guard to meet the group of refugees. He managed to hand over sleeping bags and powers of attorney for legal representation in Poland. Grzegorz Pietruczuk, the only left-wing mayor of a district (Bielany in Warsaw) offered to provide housing for Afghan families after they are allowed to enter Poland.

Fortress Europe and “Migration Diplomacy”

This group of Afghan refugees is not an isolated case. Soon after they arrived, information reached the public about nine Somalian women trapped on the Polish-Belarus border near the village of Bobrówka. Many groups of migrants, including women and children, have arrived at the Polish border to the West of Belarus and at the Latvian and Lithuanian borders to the North. While some of them are Belarusians seeking refuge from Lukashenko’s regime, many more are Middle Eastern refugees – mostly Iranians, Afghanis, Syrians, Kurds, and members of the Yazidi minority in Iraq. They’re hoping to ultimately reach the EU.

The governments of Lithuania, Latvia, and Poland are interpreting the increase in migrants reaching their territory as a threat to their national security. Speaking to the Financial Times, the Lithuanian president, Gitanas Nauseda, accused the Belarusian authorities of engaging in a “hybrid attack against Europe” by offering package travel deals via the state-run tourist agency Tsentrkurort.

On Monday 23rd August at a press briefing near the Belarus frontier, Polish defence minister Mariusz Blaszczak said “we are dealing with an attack on Poland. It is an attempt to trigger a migration crisis”. Many commentators see the reason for the current escalation at the Belarusian borders as an effect of sanctions which the EU imposed on Belarus last year. It is also an impact of the politics of its neighboring countries, especially Latvia and Poland, who present themselves as allies of the Belarusian opposition and take in people fleeing Lukashenko’s regime.

The kind of “migration diplomacy” implemented by Lukashenko is nothing new. A similar situation occurred in the aftermath of 2015 when the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan adopted a more aggressive stance toward the European Union. Erdoğan threatened to flood Europe with migrants if European Union leaders did not offer him a better deal to keep refugees in Turkey.

In May 2021, Morocco froze a deal with the European Union about managing migration to the Spanish exclave, Ceuta. The reason was Spain’s decision to offer medical treatment to Brahim Ghali, the leader of the Frente Polisario, a political organisation claiming liberation for West Sahara from Moroccan occupation. Fearing a new refugee influx, Poland is increasing its security measures on the border with Belarus by building a 2.5m high wall, similar to the one built by Hungary on its border with Serbia in 2015, and Lithuanian soldiers are installing razor wire on the border with Belarus. Turkey and Greece are both installing walls and surveillance systems to prevent asylum seekers from Afghanistan from reaching Europe.

It’s a disturbing state of affairs considering the various reports pointing out that increased border security leads directly to violence against refugees. It puts them at risk of returning to unsafe countries and leads to a disturbing rise in avoidable deaths, as countries close off certain migration routes, forcing migrants to look for other, often more dangerous, alternatives. This is a fatal sign of a failure of European migration policy. EU politics are leading to migrants being detained and subjected to gross human rights violations in transit countries in Eastern Europe, the Balkans, West Asia and Africa.

The argument propagated by the right-wing and liberal media saying that letting migrants in would favor Lukashenko and Putin is dehumanizing and acts as a cover for the real reasons why people decide to leave their homes. It is also is the main reason for the polarisation and destabilization of society. The Polish authorities are running a heated campaign using the state-owned media, presenting refugees as a threat to health, security, and stability. This has been accompanied by right wing politicians declaring the need to “protect the Polish family and guarantee security for the nation from possible terrorist attacks”. This form of fear management policy was previously used by politicians in 2015. The racist rhetoric turned out to be successful: in May 2015 72% of Poles were in favor of letting refugees in, in October 2015 – after a massive hate campaign – the support sank to 21%.

European countries have adopted policies of outsourcing migration outside of the EU to keep migrants out of their own territory at all costs. The securitisation of the EU’s asylum and immigration regime is currently funded by billions of Euros. The idea that a hard external border is important has been imposed into the European economic integration project and serves to construct refugees as the dangerous Other.

Capitalism needs borders in order to maintain its system of wealth accumulation through maximum exploitation. The borders of the European Union are entangled with global postcolonial politics of race and the global neoliberal politics of labour mobility and subordination that produce and capitalise upon these racialized differences. Poland’s policy of marginalisation and exclusion of racialized non-Europeans aims at stabilising the internal economical order. Thus capitalist territorial imaginations remain central to the European project.

Eastern European Route

The human rights violations happening at the Eastern border of the European Union aren’t new. Since 2016, activists and human rights organisations have been reporting cases of regular disregard of EU- and international law for people trying to apply for international protection at the Terespol/Brześć.

People have been camped for weeks on the train platform on the Belarusian side of the Polish border sometimes, trying to cross. The Polish Border Guards arbitrarily refused passage to refugees, mainly from Chechnya, Ukraine and Tajikistan. According to many reports, the vast majority who tried to pass at official border crossing points were returned immediately and refused the right to seek asylum. Officers refused to submit an application for international protection. The main reasons for the refusal were the lack of valid travel documents and a claim that those people were “economic migrants”.

In 2020, the European Court of Human Rights decided that Poland has ignored applications for asylum submitted by newcomers to the Border Guard officers, and violated several articles of the European Convention on Human Rights (including the order to protect against torture and inhuman or degrading treatment). There have been cases reported which expose the inhumane treatment of migrants by the Polish and Belarusian border authorities including sending back Chechen refugees to Russia and violent treatment by armed border guards.

The European Commission has maintained cooperation with Belarus since 2016, and supports it financially in the construction and/or renovation of detention centres. While the EU is sanctioning Belarus and refusing to recognize Lukashenko as the lawful president, the cooperation on migration continues. Once again, this shows the hypocrisy of the European Union’s border regime: it presents itself as a protector of fundamental rights while equipping regimes violating those rights.

Although European nations may have formally rejected their colonial past, there is still a deeply uneven and imperialist power balance between Europe and countries of the Global South. Western powers are unable to face the consequences of leading and/or participating in the imperialist war in Afghanistan, including an inability to rescue people and establishing safe escape routes. This clearly shows the brutal failure of Western interventionism and the idea of “peace and state building” which is based on domination-submission dynamics which aim to maintain the peripheral status of the region in global capitalism.

It is time to take responsibility and face the consequences of years of intended destabilization and exploitation in the region. Countries on the outskirts of the European Union need to follow international law instead of breaking it. People seeking asylum must be let into the European Union while their cases are handled. This is the minimum that must be guaranteed under the current conditions.

The Left should go even further and demand opening the borders and freedom of movement as a fundamental right. We must criticize the European asylum system and migration law, as part of global migration management, which creates and reproduces inequality and secures Europe’s position in global capitalism through restrictions on immigration. The function of such restrictions is on the one hand to maintain a high competition between workers, so that they agree to work for less, and on the other to keep the undocumented migrants down, so they can be even more easily exploited and intimidated with the threat of deportation. More restrictions will never stop migration.

The economic needs of workers struggling to make ends meet will force them to cross borders, no matter what the risk is. Borders exist almost exclusively for the world’s working classes. Fortress Europe is becoming more and more militarized, as European powers fear the uncontrolled migration from the Global South. While there are very few legal routes for migrants in the global context, for the world’s billionaires and their capital it is quite the opposite. Their capital can flow under the almost borderless globalized economy.

In The Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels declared that “the working men have no country” which means that national divisions are just another obstacle preventing the working class from realising their common interests. A common struggle for freedom of movement is an essential part of international working class solidarity and a basis to build networks of resistance.

Gallery 1: more photos from the Poland-Belarus border

Gallery 2 – photos of the protests in Poland (first picture – 2nd day of protest in Wrocław (01.09.2021). Others taken from the Pracownicza Demokracja facebook page. Reproduced with permission)