By Phil Butland and Hanna Grześkiewicz, joint speakers of the LINKE Berlin Internationals group (LAG)

We are not only aware, but we also strongly agree with many of the criticisms directed at some prominent figures in DIE LINKE. We also believe in social movements above party politics. But as we live in a liberal democracy, we cannot escape the importance and necessity of elections.

Recently, the left newspaper neues deutschland printed an article with the subtitle “as long as [Sahra] Wagenknecht is allowed to spread her theses under the umbrella of Die Linke, marginalized people should not vote for the party”. The argument was that Wagenknecht – the leading candidate for the party in NRW – has made clearly racist and transphobic comments in her new book Die Selbstgerechten. We agree with this assessment of her book.

This followed earlier criticism in May after the leading male candidate for Die Linke Dietmar Bartsch spoke at a rally in solidarity with Israel. He spoke alongside representatives from the other parties, including the AfD. We strongly condemn this (our LAG will not waver on solidarity with Palestine).

We believe that both of these politicians contradict what Die Linke should stand for, and we also know they are not the only ones. Despite this, and because of the reasons we will lay out in this text, we still urge everyone who has the right to vote to vote Die Linke in tomorrow’s election.

What does Die Linke have to offer?

If you vote Die Linke, what are you voting for? Here are some promises from the party manifesto, which is available in English:

- FIGHT POVERTY – Raise the minimum wage to €13. No-one earning less than €6,500 a year will pay more tax. Raise the minimum pension and minimum income to €1,200 a month, sanction free.

- FAIR RENTS – Bring housing into public ownership, Mietendeckel now.-national rent cap. Expropriate the big landlords. 250,000 extra social housing units every year.

- SAVE THE PLANET – Immediate free travel for children and senior citizens. Free buses and trains for everyone within 5 years. Make Germany climate-neutral by 2035.

- PROTECT JOBS – Rescue package for workers with training and job and income guarantees. Four day working week with full compensation. Better working conditions for health workers, plus an extra €500 per month.

- STOP WARS – withdraw the Bundeswehr from missions abroad. Ban all arms exports.

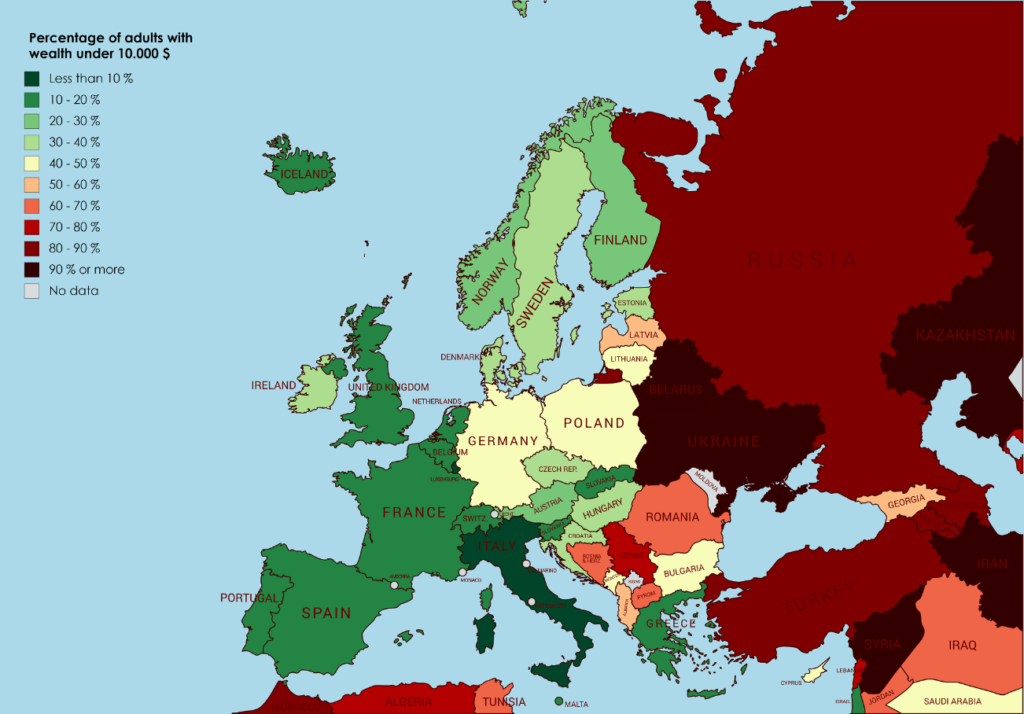

- MAKE THE RICH PAY – Wealth tax on assets over €2 million to finance the costs of the Corona crisis. Ban corporate donations and sponsorship to political parties.

The manifesto continues “It is possible to have a welfare state that protects everyone from poverty and provides good education, affordable housing and free public transport. It is possible if everyone pays their fair share. The super-rich have become richer during the Corona crisis, while many employees placed on Kurzarbeit have barely made ends meet. There is enough money. It just has to be distributed fairly and used in a way that benefits everyone. This is possible with a strong left. That is why we are asking you to cast your vote for Die Linke in the Bundestag election on 26 September!”

Why should migrants vote for Die Linke? (Or, if they can’t, urge those in their circles to do so)

Die Linke is actively campaigning for voting rights for everyone, but it also fights for the rights of non-Germans here and now. It is actively involved in campaigns against racism and fascism, and for improving the rights and wellbeing of everyone living here. The Die Linke party programme has been shaped by party members to serve all our interests.

Non-Germans are disproportionately affected by rising rents. Die Linke is the only party in the local and national parliaments which is unambiguously calling for an expropriation of the big landlords and campaigning for a national rent cap (Mietendeckel).

German and EU government policy are at fault for humanitarian crises deriving from war, climate change and poverty. This is why the party both says that ‘Refugees are Welcome Here’, and fights the causes at their root through their opposition to NATO, and the most progressive climate policy of all the major German parties.

Die Linke is not a party that disappears between elections. Party members are actively involved in campaigns for fair rents, against the privatisation of the S-Bahn, in the strikes of rail and hospital workers and much more. All these campaigns affect us all – and in most of them non-Germans are playing a leading role.

What’s the alternative? Boycott of elections?

Some people have been calling for a boycott the election for there being no viable, good, or even passable party to vote for. We – sadly – will not change the system with this single election, and the results of not voting when you have the right always end up hitting the most marginalised, and those without a vote. As leftists we urge you to vote not just for yourself, but also for those who can’t.

If numbers convince you, as this this online graphic puts it: if 100 people are entitled to vote, and of those 75 actually vote and 3 vote AfD, then the AfD gain 4%. If of the 100 only 50 people actually vote, then the 3 AfD voters gain 6%. Not all the parties are the same, and minimising the AfD’s share of the vote is important – we want to keep fascists out of power.

What’s another alternative – Other mainstream parties?

Regarding other parties who will make it into the Bundestag: the CDU and FDP were always right-wing. Both the SPD and Greens are shifting to the right and are adopting neo-liberal agendas. However, the SPD and Greens are still seen as Left of Centre.

A great illustration of the difference between Die Linke, the SPD and the Greens, and their relationship with grassroot campaigns, is the expropriation referendum in Berlin. In Berlin, at the same time as general and local elections, people will be voting in the referendum on fair rents, initiated by the grassroots initiative Deutsche Wohnen & Co Enteignen. The SPD candidate for Berlin mayor, Franziska Giffey opposes the referendum.

The Greens are also wobbling on the issue. As a report in the taz says: “the Greens recognise the aims of the referendum in their manifesto, but their formulation is cautious. They would wish “that the circumstance don’t force us to use socialization as a last resort.” And this is before any negotiations have taken place or the referendum results are known. Meanwhile Berlin’s Green transport minister Regine Günther is enthusiastically privatising the S-Bahn, as part of their ongoing campaign to woo big business.

We understand the criticisms that as they are in the coalition government, Die Linke is complicit in such developments. It is also complicit in other problematic actions of Rot-Rot-Grün. However, Die Linke senators have opposed the privatisation; and Die Linke members are active in the grassroots organisation Eine S-Bahn für Alle which unites transport unions with environmental activists.

In an article titled “The odd couple: how Germany’s Greens embraced business”, the Financial Times – the newspaper of big business – noted “It is no longer surprising to find business leaders voting Green, though the party still struggles to engage with lower income groups”. Once a radical party of climate activists, the Greens are increasingly happy courting big business and voters from the higher income brackets.

Why not a smaller party?

Broadly speaking, there are three types of small parties – single-issue parties like the Pirates and the Klima Liste; smaller socialist parties like the DKP, PSG and MLPD; and others which are less interesting to people who want to vote left. We will only look at the first two types here.

The single-issue parties have a fundamental problem in that by uniting people around one subject, they gain unsavoury support. The Pirates, for example, who campaigned against increased state surveillance, endured scandals around sexism and having candidates and functionaries who had belonged to far-right groups. Single-issue organisations, which are not built on a series of principled politics are often found wanting on other issues.

Admittedly some of the other smaller parties do have a more rounded manifesto. Indeed, if you take the Wahl-o-mat test which matches you to the party most suited to your beliefs, you may get a slightly better result for these parties. We would rather that you vote for these parties than not at all. We oppose all attempts to prevent them from standing by bureaucratic methods.

Nonetheless, in this election we are calling for a vote for Die Linke. Why? These other parties currently do not have enough broad support to reach the 5% required to gain seats in the Bundestag. Therefore a vote here will split the vote on the left and result in fewer Die Linke MPs. This will weaken any left themes, demands, and stances on the federal level.

There is also a strategic question: how can socialists effect change? We believe that social movements are more important than elections. Die Linke activists are fighting Nazis; campaigning for fair rents; and standing on the picket lines. Die Linke is also able to provide financing for campaigns like Deutsche Wohnen & Co Enteignen. In contrast smaller parties rarely have the resources to make such a contribution, and some of them lack the perspective of working with others to effect change.

To keep doing this, Die Linke needs resources, but to have resources it needs to be in parliament. As much as we might like to, we cannot and will not change the system with this election, and we have to continue the fight.

This is just one battle in a bigger fight

Whoever wins the General and local elections, we will have a fight on our hands. Even if we win Deutsche Wohnen & Co’s referendum on fair rents, the new Berliner Senat will contain councillors and parties who will do everything they can to stop it being implemented. They will try to overturn the democratic result, just as they overturned the Mietendeckel. Following the referendum to prevent housing being built on Tempelhofer Feld, the SPD tried to renege on the vote almost immediately. Mass campaigning ensured that Tempelhofer Feld was saved, and indirectly paved the way to the current referendum.

It is important that we continue to put pressure on whoever is in the next Berlin government, to ensure that our will is respected. We also need campaigns for a national rent cap and for other necessary reforms. The more people vote against the neo-liberal parties, the easier it is to bring the argument against neo-liberalism to the broader public.

What costs are unacceptable to enter government?

Die Linke should not enter government at any price. We are not fundamentally opposed to a Red-Red-Green government on a local and national level. But this is only acceptable if at the same time Die Linke stays strong in its opposition to NATO, and does not make concessions on cheap housing or S-Bahn privatisation. We cannot enter government at the cost of our political credibility.

This requires fights, both inside and outside the party, to ensure that Die Linke remains a party of social movements. The Die Linke election programme offers fundamental and radical change, but the party must continue to vocally fight for this change. We cannot abandon our principles as a bargaining chip used to enter government. This is why we need more campaigning voices inside the party.

We therefore encourage you to join the LINKE Internationals in our fight to maintain the party’s international leftist perspective. You don’t need to be a party member to join our group.

If you have any voting rights, vote LINKE on Sunday (and YES in the referendum). But this is only one battle of a much bigger fight.