Thanks for talking to us. Could you start by introducing yourself? Who are you and what do you do?

I am the co-curator of the exhibition “I Will Write Our Will Above the Clouds,” alongside A.A. We are both members of a Fana’ collective focused on critiquing the prevailing visual culture. Our primary work revolves around publishing the Black Journal, a platform for exploring politics, identity, and the contradictions between them. We mainly collaborate with artists and contributors from the Arab world to maintain a contextual perspective on these issues. This exhibition series is a new initiative created in response to the genocidal war on Gaza.

The exhibition that you’re organising is doing a tour in Europe. Where have you visited so far?

We started the exhibition in Paris, and then we moved it to London. Now we’re in Berlin. We’ll be in Barcelona at the end of next month. Then possibly Milan, Lisbon, and maybe we’ll go back to the Arab world.

What has the reception been like so far?

There was great feedback and a lot of people in Paris. At first, we were working with only 14 artists. Now we have a total of 28. The space was small and quite intimate, and two of the artists were able to come to the exhibition.

In London, we did it in the Mosaic rooms, with big help from a lot of different people. Many people interacted with the art and the artists whether through the talks or directly.

What is the exhibition about?

The exhibition is an attempt to amplify the voices of Gazan artists, and to financially support them and their families in the ethnic cleansing and genocidal war occurring till this day in the Gaza Strip. The idea is to gather the works and art that have been destroyed, bombed or displaced in this war.

This is an exhibition that focuses on the digital archive of art. What is the role of the digital cloud in times of war and such destruction? You will find a lot of artworks in smaller sizes, because we’ve got the pictures from WhatsApp [the app degrades photo quality]. Other artworks are better quality. Some artists have started using digital work only and given up on painting.

The idea of the exhibition is to sell these artworks. Given that some of the original works do not exist anymore, the idea is to price these artworks with the artists in such a way that it will finance them.

A lot of the art that we have is from during or after displacement. One of the artists drew the series when she moved to Cairo. Other artworks are from the COVID era, but they still remain relevant today.

Did Gazan artists have problems before the current genocide?

They were silenced, surveilled and even arrested. It was hard for them to acquire art supplies because of the imposed siege. It was even harder to circulate their artwork outside Gaza for the same reason. Art exported from Gaza was never insured or guaranteed to arrive. The Israelis will most likely confiscate and destroy these artworks so it is always difficult to see what is being created in Gaza.

Is it possible for artists to produce new art in Gaza at the moment?

Some artists are producing and documenting the destruction and daily details of what is happening. In a converstation with artist Mustafa Muhana who produced new work for this exhibition, he mentioned how important it was to create during this time to remind himself of his human side. Same for the artist Basel El Maqousi who we can see on his instagram account, he drew because he want to be reminded of his humanity.

Creating art in these times does not take the same course for everyone, as artists have the space to think creatively and be inspired. I think their processes are different than what we can imagine. Samaa Abu Laban tells us that it is very hard to aquire any type of art supplies and they have to get creative by recycling old paper. There is an urgency to produce, to document and to express, but death occurs every single second around them.

Do you think that art can play a role in resistance?

In these times, art and culture are only meant to amplify the voice of the resistance and the people of Gaza. That is their only role as we see it.

This weekend, you’re exhibiting in Berlin. I’m sure you are aware of the clampdown on culture in Germany, particularly regarding Palestine. Have you had any problems organising the exhibition?

We spoke with more than ten exhibition spaces, none of which offered space for us—except for Panke Culture, where the exhibition will take place. Germany has become a ground for censoring everything related to Palestine. Not only this, but the government is directly funding the genocide. Recently, we saw the German foreign minister justifying the bombing and targeting of refugee shelters in Gaza; she said that this is what Germany stands for.

We had a lot of doubts about coming to Berlin, but we got a lot of calls from our communities here that they want to support, and I really thank Panke for offering the space.

Can artists contribute somehow towards stopping the ongoing genocide?

Any person can, artists or not. The idea is to mobilize and to work on all different platforms in parallel. It’s easy to believe that our fight has no direct influence on this billion dollar genocide, but I think it’s time we gather, rally and organise, first to stop this annihilation and second to rethink our relationship to Western values that have governed this world for such a long time. No longer we can tolerate the hypocrisy and the double standards, Arab, Black and Brown life is valuable and precious and it is time that we unite against the vicious white supremacy and settler colonial mindset that kills our people all around the world.

In the last couple of months, Israel has exported the genocide to Lebanon and also to the West Bank. How is this affecting you personally?

This is not new. This time it’s more violent, televised, documented. It’s ridiculous to watch the genocide on the tv and on your phone, even if you hear it around you. What is happening in the West Bank and Lebanon is part of the same annihilation war on Gaza with different techniques, what started in Gaza now can be seen happening in Beirut, Tulkarem, Jenin and all around the Levant. We are all togther in this, until the occupation ceases to exist.

As you say, this is not new, but it looks like it’s getting worse.

It is already worse. We have crossed the point of no return to the old status quo.

Are you able to stay optimistic about the future?

It’s really very difficult. There is a lack of focus a lot of people I know are sharing. There is no planning for tomorrow, or for after tomorrow, because you really have no idea what’s going to happen. There is crippling anxiety about the future and the present, and the normalisation numbs you, but it’s a way to cope.

But amid all of this, we see a liberated palestine!

To finish off, let’s return to the exhibition. Where is it? When’s it open? How can people visit it?

It’s opening this Thursday in the Panke gallery. You can purchase your tickets online or at the door. Following the launch of the exhibition, we have a series of film screenings in ACUD studio. We have some Palestinian films and some recent films from Gaza. Most are shorts, but not all of them.

Then the exhibition is open on Friday and Saturday, and on Sunday we have a finissage with some readings, artists’ talks, and some music at the end.

Can you say more about the readings and the music? What’s being read? What’s being played?

The readings will probably be from a Palestinian poet and a Palestinian writer, all the old words that are still relevant every single day. The music is going to be by a DJ from Palestine who will be playing a set.

For people who can’t make it, is there any other way they can support you and Palestinian artists?

There is a donation box on the ticket website. These donations go directly to Sa7ten in Paris, which is an organisation that we’ve been working with since the start. They are in direct connection with a lot of people in Gaza. They send these funds to Gazans. They cook for a lot of groups in Gaza.

Is there anything else you’d like to talk about that we haven’t covered?

We thank everyone who worked with us along the course of the last three, four months to open it in a bunch of cities. We thank the artists for trusting the process and contributing to this exhibition. We want their life’s work to be seen by all these people.

This series of exhibitions that are happening really made us connect with artists from Gaza, some of whom became really good friends. I hope that one day we will be able to meet face to face.

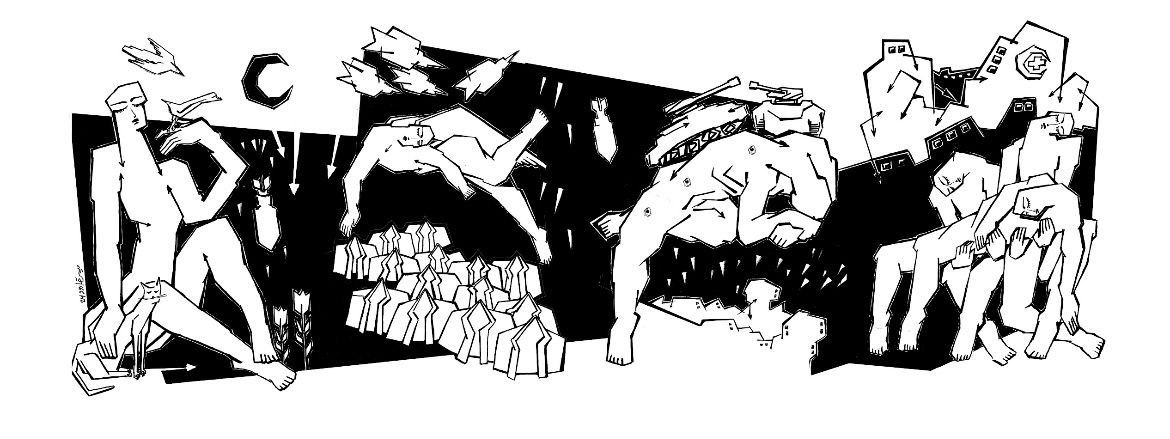

“I Will Write Our Will Above the Clouds” is a compilation of printed images depicting what were once physical artworks. These images capture the transient and precarious nature of existence in the war-torn landscape of Gaza. The exhibition features the works of twenty four Gazan artists who turned to digital platforms to archive and preserve what might have otherwise been lost. These digital imprints, with their inherent intangibility, mirror the reality of life in Gaza and serve as metaphors for the fragmented memories and disrupted lives of the artists. When pieced together, they create a disjointed but powerful mosaic that challenges traditional forms of exhibitions. “I Will Write Our Will Above the Clouds” invites viewers to experience the oscillation between presence and absence, the real and the virtual. The works confront viewers with the raw and unfiltered realities of the artists’ experiences, pushing the boundaries of digital expression.

Adel Al-Taweel, Abod Nasser, Adam Mghari, Amal El Nakhala, Bayan Abu Nahla, Hassan El-Zaneen, Jehad Jarbou, Kenan Aburok, Khaled Jarada, Mahmoud Al Haj, Marwan Nassar, Maisra Baroud, Mohammed Al Haj, Mona Jouda, Mustafa Mohanna, Samaa Abu Allaban, Shereen Abedalkareem, Walaa Shublaq, Yara Zude.