This article is meant to act as a response to Joseph Choonara’s series of talks on whether or not workers in the Global North benefit from imperialism in the Global South. While different variants of this talk have been presented to a number of leftist groups in London and Berlin, I am responding to the version of the talk presented at the Socialist Workers Party’s Marxism festival in London. In this article, I briefly summarise Choonara’s main positions, some of which I agree with, and then proceed by responding to those that I take issue with.

Global North workers

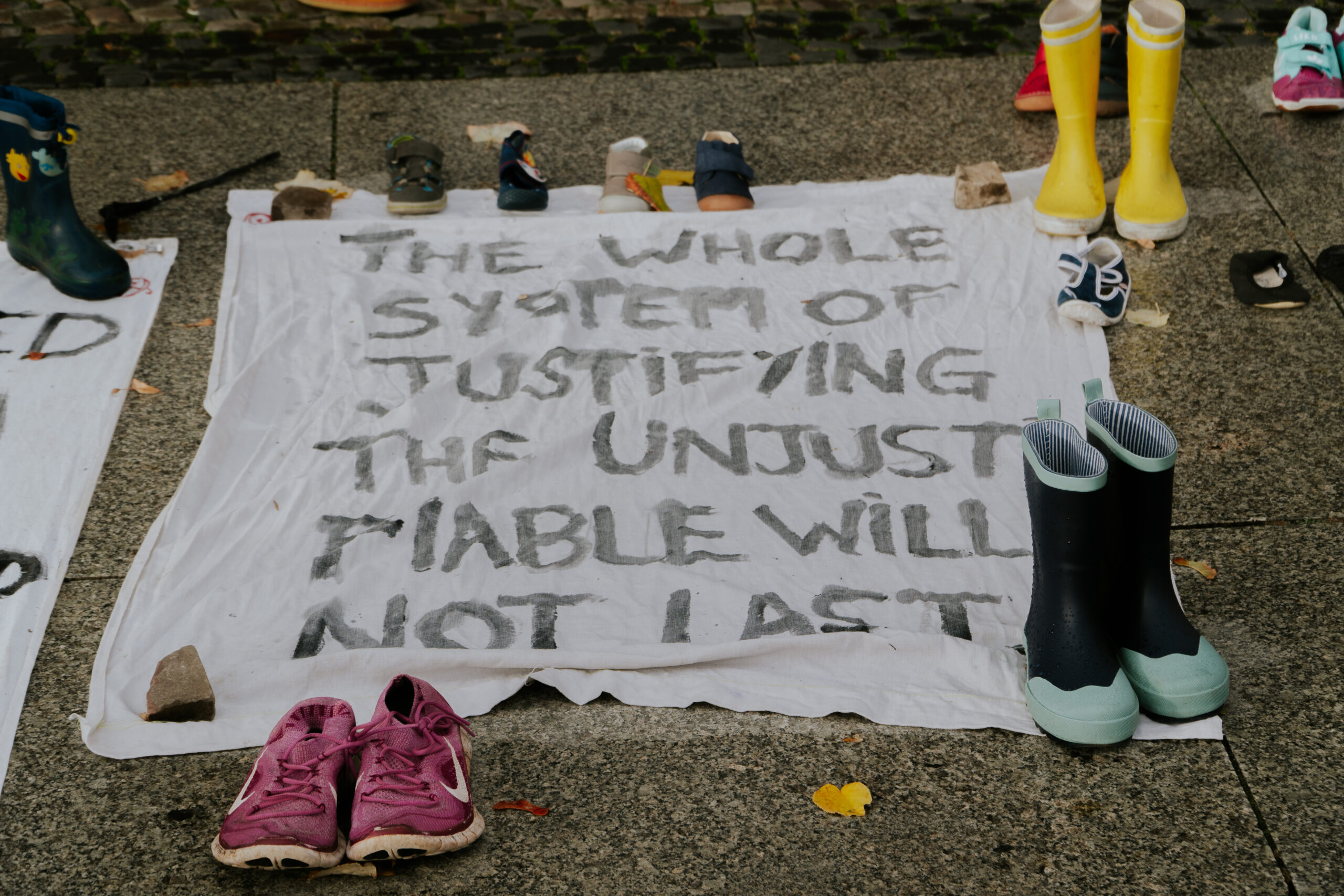

Choonara begins his talk by discussing the gravity of his theory, in light of the hundreds of thousands of British workers pouring out onto the streets in solidarity with Gaza. If he is wrong, he claims, then the only reason these people are protesting is because of morality; their material interests are tied to imperialism, and therefore to Israel.

He then states that he is not claiming that living standards for British workers are somehow lower than or even equivalent to living standards for workers in Global South countries like Bangladesh or Chad. He also does not debate that imperialism has ravaged the world, and helped birth capital, which (quoting Marx) “comes dripping from head to toe, from every pore, with blood and dirt”. Having said that, he takes objection to dependency theory, which states that there is a flow of value from the Global South to the North, and the theory of a labour aristocracy, which states that the interests of workers in the North lie with capital, due to how relatively well-compensated they are.

His issues with dependency theory lie in that it allegedly replaces the ideas of exploitation on the basis of class with ideas of exploitation on the basis of nations. This leads to a core of nations (the capitalist class) and a periphery (the working class), together with a semi-periphery (the middle class). He claims that this obscures class divisions within nation-states, and, more importantly, obscures the mechanisms through which value flows. The birth of capitalism in Britain was due to the specificity of exploitation as a form of labour under capitalism. The same mechanisms that benefited from the slave trade and colonialism, through the processes of primitive accumulation, transformed British farmers into a doubly-free worker: free to sell their labour, free of the ability to reproduce themselves. Dependency theory, by decentering exploitation, obscures its novelty and effectiveness as a mechanism of accumulation.

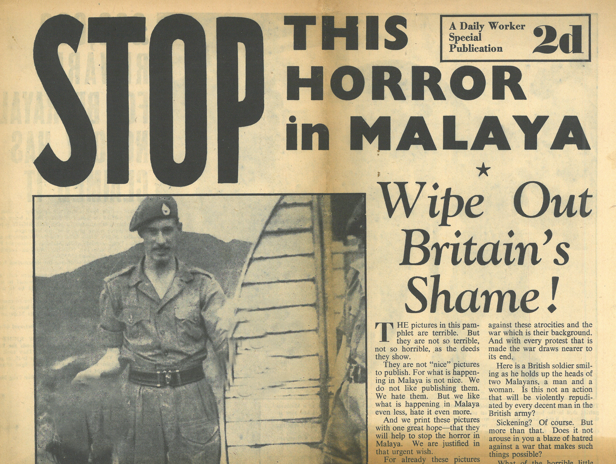

Moving onto slavery and colonialism, he says that slavery ended due to slave revolts; colonialism in broad swathes of Africa and Asia came to an end after the Second World War, partially because the United States wished for the more capitalist subjugation of these markets. Colonies became less critical to profits, and were left in a state of malign neglect; Northern capitalists attempted to substitute Southern resources with domestic alternatives, oil being an exception. His explanation for the perennial underdevelopment of the South is that capital is directed towards where profits can be generated. This is where one finds clusters of highly educated workforces, large amounts of fixed capital, functional infrastructure, and so on: the global North.

China, he claims, is rather exceptional. China’s meteoric economic rise to being the world’s production hub cannot be explained by dependency theorists. The people that derive their wealth from Chinese growth are exclusively capitalists (who are egalitarian, in that they only care about profit). China, too, has seen the birth of a colossal domestic bourgeoisie, and the rise of massive inequality. Yet, capital remains predominantly focused on Northern Europe, North America and Japan.

Finally, Choonara ends with two problems that dependency theory turns up. First: how do we mobilise British workers if capitalism works in their interests? Second: do we tell Global South workers to strike deals with their own domestic capitalists?

***

If I had to hazard a guess, there are three historic motivations for Choonara’s position. The first of these is that import substitute industrialisation—the idea that the South needed to shut off imports from the more developed North to fuel internal industrialisation—has tended to fail where it has been attempted. The second is that the Global South bourgeoisie does tend to view colonialism as some sort of balance sheet, cynically using the most absurd market valuations of “colonial plunder” to further their own political careers. Finally, the bourgeoisie in the Global South have indeed often succeeded at using postcolonial nationalist fervour to rally “their” workers for “their” cause. For instance, the recent outpourings of grief in India after the death of the industrial capitalist Ratan Tata exemplifies how real this absurd phenomenon is.

Motivation aside, however, Choonara’s interpretation is rather blind to how profits are made and redistributed in the contemporary economy, which is the focus of this article. I shall begin by addressing how Northern capital benefits from imperialism; I shall then follow up with how these advantages are absorbed by Northern labour.

Capital

Choonara is correct that exploitation is the source of surplus value and capitalist growth. However, as theorists since Rosa Luxemburg have been pointing out, capital is subject to frequent crises of profitability, or barriers to its own expanded reproduction. This forces it to rely on spheres of the economy located outside capitalism to offset these crises, such as gendered labour, or racialised labour in the global South. Particularly in the colonial context, these crises were partially offset through cheap resource inputs from the colonies. In Britain, for instance, this included sugarcane from the Caribbean, cotton from American plantations, and later, oil from Iran (p. 94). They have also been offset by turning colonies into (non-competitive) markets, allowing for the expansion of capital located mostly in the core, often mediated via capital in the periphery. This was India’s primary role within the British Empire. Balance-sheet analyses of “how much money was drained from colonies” can actually end up obfuscating these mechanisms, and validating vulgar economism: resources expropriated from the colonies were undervalued by design.

These periodic crises also serve as an explanation for China’s rise. Choonara is correct that China cannot be explained by dependency theory: Dengist reforms and the rapid integration of Chinese Special Economic Zones (SEZs) into the world economy was the exact opposite of what many dependency theorists recommended. Deng’s reforms instead created a Chinese bourgeoisie who drew massive profits from the exploitation of Chinese workers, but also drove colossal economic growth for decades, effectively turning China into a microcosm of capitalism itself. But China also represents a bit of a problem for Choonara’s framing. His claim that “capital clusters in the North because profits are higher there” fails to explain why industrial capital moved to China in the first place. A popular analysis of this shift has involved ascribing it to the relative collapse in the rate of profit in the global North’s industrial sector, due to rising productivity and growing wages through organised workers’ movements. Under these readings, this collapse in profitability is what first sparked American industry’s shift to Germany and Japan, followed by South Korea and Taiwan; and finally, two decades ago, to China. Choonara’s repeated insistence that China is an exception is rather iffy. As critics of the winners of this year’s economics Nobel have pointed out: if China or India are exceptions to your model, you need a new model.

Choonara is correct when he says that capital is attracted to where the most productive workers lie. Following the deindustrialisation of the Global North, Northern labour has flooded into the service sector. Britain today produces very few goods: manufacturing accounts for around 8% of both GDP and employment. The majority of British workers are employed in the tertiary sector, which includes fields as diverse as finance, IT, fundamental research, medicine, care work, etc. Some of these roles are intrinsically resilient to real subsumption, and lack clear notions of productivity: a barista or a schoolteacher are equally productive all over the globe (if not more productive in the Global South). Other roles, particularly those that employ highly skilled workers, do generate massive profits. This is where the third volume of Capital becomes relevant. The distribution of profits and rents in the economy, Marx is clear to point out, need not necessarily align to the generation of surplus value itself. As Caffentzis puts it, profits are more of a “field variable” (p. 119), a result of a transformation process applied to societal surplus value. It is precisely this phenomenon that dependency theorists have concerned themselves with: the global North’s use of political power to redirect the surplus value generated in the South towards the North. This does not in any fashion preclude domination by class being the primary mechanism of accumulation, as Choonara would claim it does.

In a contemporary economy, the profits generated by much high-end labour are not necessarily generated through expansions in productivity and output, but rather through their ability to enable this redistribution of surplus value. This is done through a broad range of mechanisms that I shall briefly touch upon.

One of these mechanisms is financial capital, which works to maintain expropriative tendencies in the Global South. This is done through organisations like the IMF, that tether the productive forces of the Global South to Northern credit lines, destroying state capacity through forcing endless reforms. This helps spawn a domestic bourgeoisie, and is also why leftist strategy should not involve pushing citizens of the global South to compromise with their capitalists. First, this class is tiny: it is unclear that a labour-capital compromise in the South would do much to raise living standards. Second, this class often ends up acting as a comprador class, raking in profits while shuffling even larger profits higher up the value chain, mostly to Northern firms. An examination of H&M’s value chain ought to illustrate this perfectly: no Bangladeshi mill-owner will ever approach even a fraction of the wealth of the Persson family.

Yet another mechanism includes the generation of intellectual property, maintained through diverse, shifting mechanisms, such as patents or data holdings. Global North states are able to leverage their highly educated populations to attract both highly educated workers in the South, as well as actual surplus value generated in the South. This is ensured through the creation and the enforcement of ownership over these artificially scarce assets, protected by international law and enforced via treaties like TRIPS. Similar mechanisms increasingly permeate into industrial manufacturing, in countries like Germany or the United States (or critically, Taiwan): patents that protect high-tech manufacturing ensure continual surplus drain from countries that lack the capacity to generate IP at scale.

Often, these processes are accompanied by attempts to shut down Southern productivity where it does exist, forcing payments up the value chain. An example of this is the decades-long battle to force the Indian pharmaceutical industry — which supplies most of the Global South with generic drugs — to recognise intellectual property rights (India presently retains the legal right to ignore international drug patents if there is a major public need for a drug). More recently, the utility of user data in contemporary capitalism has led to Northern corporations actively lobbying for monopoly positions in data extraction: see, for instance, Meta’s Free Basics scandal in Africa.

Labour

One might argue, at this point, that the search for profits benefits capitalists and not labour, whose interests lie in the abolition of capital. But labour has another, more immediate interest than the abolition of capital: it is the consumption of use-values. Being a worker is universally alienating, but alienation is a lot less bad when you only have to work 36 hours a week, mostly at a desk job, and when you can afford to buy a lot of commodities with your wage. Northern states have the capacity to ensure precisely this compromise, to ensure its smooth functioning and reproduction. States aid capital in creating and enforcing the legal mechanisms that allow for the smooth appropriation of surplus value; in exchange, capital transfers part of this appropriated surplus to states, allowing them to retain the capacity to create enough of a welfare state that domestic dissent is quelled. The ability that Northern states have to tax and redistribute surplus value (often generated elsewhere, often through the use of resources expropriated from elsewhere) is what quells domestic workers’ movements. Capitalists have framed the welfare state as a compromise between domestic capital and labour. They are correct.

This is precisely the argument that many dependency theorists have made; to accuse them of “replacing class with nation” is a colossal misrepresentation. Yes, exploitation and expropriation do exist in the Global North. But the former is often offset through the receipt of wages higher than the surplus value generated by the worker. The latter falls squarely onto a range of insecure populations: such as migrants, held captive to migration regimes that kill their capacity to organise, and allow capital to treat them as entirely disposable workers through the very enforceable threat of deportation. To address Choonara’s question about mobilising British workers: capitalism is not going to be overthrown by British workers. It is in the interests of workers in the Global North to retain their reformist sensibilities and struggle for a restoration of the welfare state. This will not change without mass movements in the Global South that de-link both their resources and their labour from the North, redirecting their productive capacities towards instead producing domestic use-values, rather than luxury goods for Northern citizens.

To ignore this is to ignore reality. The Northern working class fully recognises their position, which is simultaneously both privileged and precarious. The desire to maintain this and to win some compromise explains the massive popularity of anti-migration reformists like Sahra Wagenknecht, or of MAGA communism across the pond. As long as Northern states retain their ability to mediate bargains between global capital and domestic labour, this progression is inevitable.

Compromise

Today, the mechanisms of expropriation and of the transfer of surplus value from the Global South as profits and rent towards the North appear to be increasingly turning inwards. This is neoliberalism manifest: the same processes of subjugation forced upon the Global South have been granted increased freedom, in the wake of profitability crises, to inflict the same horrors upon Northern citizens. This has been particularly true in the aftermath of 2008, where quantitative easing (QE) has resulted in extraordinary freedom for capital, and these processes of commodification have accelerated all over the globe. Financial capital, for instance, has embarked upon a program for the rapid privatisation of assets previously held by the state, such as public transport, housing and even healthcare. This follows market principles: these commodities are affordable, but for high-wage workers that enter the hallowed halls of finance and tech. Ultimately, this growing wage gap has sparked growing polarisation in Western economies, and is potentially the cause of the renewal of radical politics beyond the end of history.

But times change, and political economy with it. The Western world appears to have begun an orderly exit from neoliberalism, precisely now that capital accumulation outside the core has accelerated. There have been signs of this reversal for decades: already in the 2000s, Brazilian and Indian capitalists had begun suing the United States for its anti-competitive agricultural subsidies. QE might have extended neoliberalism’s longevity somewhat, but perceived Chinese belligerence and the COVID supply chains crisis have led to de-risking becoming an increasingly consensus position in the US. Europe remains more split, partially due to German economic imbecility. German capitalists dream of selling cars to the Chinese middle class, and appear to take some perverse pleasure in impoverishing Greeks; at this point, this fetish goes against the better judgement of even orthodox establishment economists like Mario Draghi.

This has the potential to lead to a grand restoration of labour movements in the global North. Now that essential production is less inclined to move to China or Vietnam, labour could win back its fading ability to compromise with capital by asserting control over their own states through labour movements, just as they did in the past. Whatever revolutionary fervour exists in the Global North can be quelled: the labour-capital compromise is, at the cost of the Global South, something that can be attained. Congolese tantalum will continue to enter Chinese suicide-proof factories for consumer electronics; the productive forces of Bangladesh will remain devoted to spinning yarn for Northern luxury brands as their own country disappears into the Indian Ocean; the deforestation of the Amazon and the Indonesian rainforest will continue so Northern consumers retain easy access to the finest hazelnut chocolate spreads. Smaller, wealthier European nation-states are a template for this paradigm. Their economies tend to consist of highly-educated service workers engaged in generating intellectual property. High taxation, and union-driven wage negotiation ensures both that the proceeds of capital are distributed to workers, and that rapidly growing wage discrepancies do not upset domestic markets. This is accompanied by rigid migration systems (such as in Denmark): ensuring, in practice, a system that works mostly exclusively for highly-skilled workers that will join the IP/patent-generating masses.

***

I would like to raise a counter-problem to the challenges that Choonara has raised. In light of the fallout from 2008, many Southern countries have fallen deeper and deeper into economic stagnation and an active de-development that rivals the colonial period. This is increasingly impossible to ignore. At this point, the extractive tendencies of Northern capital are clear to most heterodox economists, and even a subsection of the orthodoxy. The average early-20s liberal activist is fully aware of the conditions in which their chocolate and coffee are grown, or their 118 items of clothing are produced (what they choose to do with this knowledge is, of course, a different story).

Someone who has grown up in a Global South country integrated into the world economy has likely either experienced or witnessed gruelling labour conditions, and is fully aware of how they end up generating profits for Northern firms. For the lucky few that end up moving to the North, what they see is a crumbling but still intact welfare state, with leisure time and a bountiful surplus of commodities and services, many of which are subsidised by precarious labour in their home countries. In the absence of a movement that genuinely acknowledges the role imperialism plays in subsidising Northern lifestyles, many of these workers will be driven to reaction, driven more by a desire to “discipline” the “lazy” than to actually collectively liberate humanity from exploitation.

When all is said and done, Choonara and other developmentalist-Marxists are perfectly entitled to their own analysis of things. What is rather poor form, however, is to present these analyses as if they were established fact: as if Marxian analyses of the utility of colonialism were fringe tankie opinions, and critical analyses of the welfare state were revisionist heresy, tearing apart the unity of the workers of the world. This goes beyond being merely poor form, and becomes actively harmful when presented to an audience of newly radicalised Northern citizens, as an invitation to participate in some sort of collective moral redemption, but in a leftist fashion.

***

Finally, a few finishing notes. Choonara refers to Saudi Arabia (and presumably other petrostates, like the UAE and Qatar) as “Global South” nations. This is quite a strange usage of the term. The Gulf features some of the highest incomes for citizens in the world; they feature extensive welfare states, near-0% taxation, and require very little labour from citizens. The labour forces in these countries tend to be migrants with no pathway to permanent residence, let alone citizenship. Many of them work in non-free conditions akin to slavery, with routine passport confiscations through the kafala system. But more importantly, these nations are very much part of the informal American empire. Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar are major non-NATO allies; Saudi is frequently referred to as an American client state, with good reason. The sole exception in the Gulf is Iran, a country that has been wrecked by sanctions since the Revolution.

Next, the planet. At this point it is abundantly clear to everyone that there are planetary limits to consumption, and that consumption patterns simply cannot be extended to the entire world. This provides an almost trivial counterargument to Choonara’s claims: the consumption power of the Northern (particularly American) worker, in an egalitarian world, must necessarily collapse. This is definitionally against their interests.

Finally, concerning Israel. It seems to me to be rather uncharitable to refuse to credit British workers with even a shred of morality and camaraderie. Yes, these workers benefit from imperialism; this does not mean that they will blindly support imperialism’s absolute worst excesses, especially not if they are workers whose ethnic or religious identity emphasises solidarity with Palestine. This wasn’t true during the colonial period, when abolitionism and Home Rule societies thrived in England, and there is no reason it should be true today. And it would do us good to remember that not all forms of imperialism serve the same purpose or are equally useful. The establishment of the State of Israel may have been in the interests of Western capital, but at this point, it is unclear what anyone in the West gains from Israel’s expanding, genocidal campaign. At this point, the Western world appears to be lumbering towards slow political suicide, under no force other than its own sheer inertia.

Good. The sooner it dies, the better.