Editors’ Note: This interview was taken on 8th June, the day before the occupants of the Madleen were kidnapped by Israeli troops on international waters. We will update you with more news as quickly as we can.

Hi Yazan, thanks for talking to us. Could you start by briefly introducing yourself?

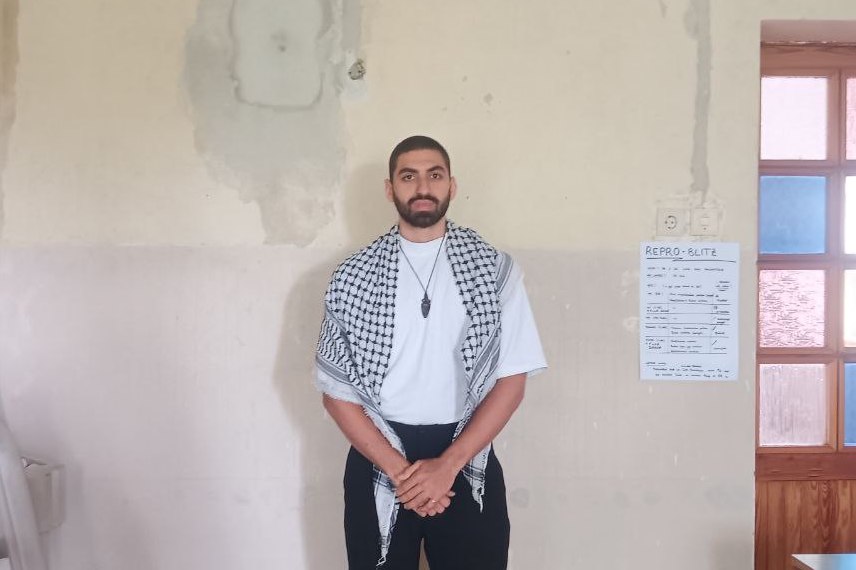

My name is Yazan Eissa. I am a Palestinian in exile. I have been living in Germany for seven years already. I am a representative of the Freedom Flotilla in Germany and a steering committee member.

When did you become an activist, and why?

Although I’m not a big fan of the word “activist,” I can say that as a Palestinian, I’ve always resisted the occupation one way or the other. However, ever since October 7, the masks have fallen, not only for me, but for anyone else around the world.

The governments of the world started taking sides. Capitalism has shown its colours, colonialism and Zionism have become more prominent in the way the governments respond to everything. It was just clear to me that I have to do as much as I could to cause a change in this world.

How did you get involved with the Freedom Flotilla?

I simply couldn’t take it anymore, sitting there being helpless. The inability to do anything pushed me to contact as many direct actions as possible, offering my help. I contacted the Freedom Flotilla repeatedly without response. When I found out that a steering committee member was moving to Germany, I contacted them and offered to help start the Germany team.

What inspired you specifically about the Freedom Flotilla compared to other efforts since October 7th?

What really stood out for me was that the Freedom Flotilla had started way before October 7th. It was about the siege of Gaza. It’s the values carried by this organization. Those people actually know about the struggle in Palestine. I realized that even more after joining and talking to them. They’re doing this for the right values and the right cause.

I really wanted to join them because they were advocating for direct action. Different organizations have different approaches, but for me it was direct action that could make a difference. We could cause turmoil. We could start the butterfly effect.

Can you tell us about your involvement with the Conscience?

The Conscience is a big ship, and, along with the Madleen, it was set to take almost 50 people to Gaza. I was one of the people who was willing to be a participant and go all the way to break the siege.

But as we were trying to get things started, the Zionist entity took notice of our movements and tried to stop us. First through bureaucratic warfare, then by removing a flag from a ship in international waters––breaching maritime law. They finally resorted to dropping a bomb on the engine of the Conscience and destroying it. They thought this would destroy our hopes. But 2 weeks later, we organised the Madleen to deliver the aid.

I guess most people know about the Madleen because of the involvement of Greta Thunberg. How important or unimportant is her involvement?

Speaking to Greta, I know for a fact that her values are in the right place. This is something that made me very comfortable having her on board. In the beginning, we asked her to be there as a prominent figure but not be on the ship. Then she decided: “this is something that I would stand behind. I want to be on the ship.” That’s something we hold a lot of respect for.

Prominent people are more than welcome to be on board, because this means more media and less risk of our comrades being attacked. It was a very strategic decision to make. Rima Hassan, a French parliamentarian, is also aboard.

The Madleen is not able to take much food, and at the moment thousands of children are being starved to death in Gaza. Is this just a symbolic action?

A year ago, we were trying to deliver 50,000 tons of aid, using the Conscience and other ships. We know that even if we were to take a small ship and load it as much as we can with aid, it would not be enough for a single day in Gaza.

But we’re doing our best, and that’s why we decided to create a storage area in front of the ship. We even bought barrels, filled the barrels with aid, and then just tied them on board the ship. When you see the pictures of the Madleen, you can see those brown, weird-looking barrels that are filled with aid.

We also understand, regardless how much we take, it would not be enough for the humanitarian aid to Gaza. But it is not only symbolic, because our main goal is to break the siege on Gaza. We want to open the humanitarian corridor so other ships can join us. After that happens, the siege will be broken by land. From the beginning, our goal was to break the siege on Gaza.

The Global March for Gaza is starting next week. How are you coordinating with what they’re doing?

A strategic alliance has been made between the Global March to Gaza and the Freedom Flotilla. They simply share the same goal of breaking the siege on Gaza, so it’s very natural, very organic, that this would happen. As a grassroots movement, we decided not just to break the siege of Gaza by sea, but also by land. Having these all together adds to the idea that the siege is illegal and inhumane.

How are people in Gaza responding to the Freedom Flotilla?

We have received a lot of support from Gaza; a lot of videos that are emotional and eye watering. They view any sign of hope, any uprising by free people, with happiness. Seeing that there is even the slightest reaction from the people in Gaza is so powerful and motivating for us.

Gaza is basically our soul right now, and our soul is slowly dying. They are killing people by the hundreds every single day. Any form of hope that comes from Gaza is amplified a million times and moves millions of free people around the world, causing waves of resistance from the outside.

How easy is it for you to stay hopeful?

It’s really not easy, especially with hundreds of people dying every single day. With every martyr who is killed by the Zionist entity, it makes it more difficult to be hopeful. However, it brings together communities, and makes us want to gather our strength and to move forward.

When we are not resisting, what are we doing? We’re sitting there at home alone, unable to feel, unable to move, unable to live. We experience a collective suicide that is experienced by every single individual on their own.

We send out a little boat to Gaza, which gets reciprocated by a small hope from Gaza, which gets amplified a million times. This is the way that our energy keeps on adding up and multiplying and amplifying, and the hope starts lightning from this lighthouse.

It is one fight. It is one monster we are facing. The only way to defeat it is by putting our hands together and fighting.

There’s been attempts to break the siege before, most memorably the Mavi Marmara, where two German MPs were on the boats. That got attacked by Israeli troops. What’s the likelihood that this will happen again?

If we look at the different missions that came after 2010, the Zionist entity has realised that it’s not in their interest to go on the ship and kill activists and journalists. They had to pay for that.

I really think that because of the strong media presence that we have this time, because all eyes are on us and because the Zionists are losing the grip of their narrative, this will add to our security and hopefully what’s happening right now will not be similar to what happened on the Mavi Marmara.

Could you say a little bit about the change in narrative? Last month, we had Friedrich Merz, Annalena Baerbock, Emmanuel Macron, and Keir Starmer all saying that maybe Israel has gone a little too far. Why do you think that there’s been this shift in how our politicians talk?

Right now, we are reaching a phase where the masks are being removed, where the Zionist entity is losing its grasp of reality. People are seeing what has been going on in Palestine since 1948. They are looking back into the records and a lot of people around the world are starting to wake up; to realize.

The metaphorical ship of the Zionist entity is sinking. And the partners complicit in this genocide, including Germany, have started to realize this. So it’s a way for them to abandon the ship, to save themselves a little bit by saying: “Now we realize what’s happening is a genocide. Now we realize that we are standing on the wrong side of history.”

One day or the other, the Zionist entity will fall. People are starting to lose hope in the Zionist narrative, and that’s why a huge shift in narrative is happening around the world.

What are the different scenarios which could happen to the Madleen in the next couple of weeks?

I think the best way for them is to actually let the ship enter and provide the aid, even if it means they would lose the inhumane siege they have been upholding all those years. The other alternatives would not help them. If they board the ship and injure any one of our comrades that would not come back positively on them.

It’s also a possibility that they occupy the ship, take it to Ashdod port or Haifa, put the activists in prisons, and then deport them. Our comrades have practiced non-violent resistance. They know what to do there, and they will try their best to make sure that no one gets injured during this process.

Another scenario, which is, in my opinion, the least likely, is that they would just drop a bomb and kill everyone on board. I do not think that would be a smart move for them, and that’s why I believe there’s a really small likelihood that this thing would happen. But once again, we’re dealing with the Zionist entity, and who knows how far they’re willing to push this.

What happens next?

Since the beginning of the siege, our idea has been to keep sending ships until the siege is broken. I hope that we do not have to send even more ships, but we are going to send as many ships as we can to end this siege.

What is your next step, personally?

I want to be more part of this global uprising. I want to take part in the social movement of decentralizing away from the government.

I received my Bachelors in renewable energy engineering. Currently I am pursuing a Masters in electrical engineering. I think it would be beautiful if I’m able to use my knowledge and my skills to create electrical grids that are not connected to the government and used in a way that upholds human values and does not destroy the environment.

This would be a form of launching point, or a base for more social movements where everyone is accepted; everyone is united. We live life the way it’s supposed to be, and then hopefully an example for humanity to just go deeper in that sense and build this new future that I am dreaming about.

What can people do to actively help the Flotilla?

What they need to realize is that this is not a fight for specific people. It’s not only the 12 people on board who are leading the fight. It’s a fight that involves every single person of the free world, and they are part of it. We have so much power in the collective. Putting our hands together and working together would move mountains and not just stones. Freedom Flotilla will soon publish a form for people to join us on the next mission, to participate in any way they can.

Right now, we are approaching a very tense and critical time with the Madleen, because they are less than 24 hours away from Gaza. We have already been receiving threats by the Zionist entity. The latest threat is that they are going to deploy commandos to board the ship. Those specific commandos with the specific numbers and specific names have been involved in multiple war crimes in Gaza. They’re also going to employ ships and helicopters just to stop this small boat. So it’s going to be a very critical time.

What could be done right now is to not leave our comrades alone on the waters in that ship. Send letters to the government in Germany, for example. German citizen Yasemin Acar is on board that ship, and the German government is obliged to provide security for a German activist who is just upholding the ICJ laws and following the Geneva Conventions and the UN laws to provide humanitarian aid to Gaza.

We should send as many letters and emails as possible to the German foreign office and the Zionist entity’s embassy in Germany. Maybe they won’t read them, but maybe we succeed in causing so much disruption in their system and jamming their signals with the phone calls that they are forced to have a look and see what is going on here.

This is only one of the things that we can do at this specific moment in the next 24 hours where times are critical.

What is possible in Germany?

I was speaking to a German once, and he told me that what’s happening in Palestine right now is liberating us in Germany. It is making us wake up and see what Germany is doing to us. We do not in fact live in democracy. The amount of people whose houses have been raided by the police for standing firm for Palestine, these are things that should not be silenced.

We, as people, need to draw our boundaries, to tell the German government that this is not all right. If Germans believe in freedom of speech, it doesn’t come at an easy cost.

Risks are part of it, but it is a global uprising, and it’s happening everywhere else in the world. It’s up to the German public now, whether they choose to be part of it or choose to be complicit in the genocide happening in Gaza.