For three freezing months over the winter of 2022, Sharmila, an international student from India, biked across Berlin delivering food for Wolt. She followed every ping on the app, waited outside restaurants in the cold, and messaged support when things went wrong. “I was tracking hours like an employee would,” she later said, but unlike an employee at virtually any other job, Sharmila was never paid.

Between November 2022 and January 2023, Sharmila worked through Wolt’s app, navigating a digital interface that issued orders and scheduled her shifts. But the job wasn’t with Wolt directly, at least not on paper.

Instead, she had been routed through a third-party subcontractor or so-called ‘fleet partner’ Mobile World, a phone shop on Karl-Marx-Strasse run by a man named Ali Imran. It was Imran who collected her documents, set up her rider profile, and promised regular payments. When the first payday passed without wages, she was told there were delays. A month later, the same excuses followed. By January, Sharmila was owed over €3,200 and still hadn’t received a single cent.

She wasn’t alone.

Ashish, another international student from India, first joined Wolt in 2021 on a direct contract. He was hired through a recruitment ad, issued gear from the company’s Ostbahnhof office, and trained to use the app. The work started off steady at €4.70 per delivery, plus tips and bonuses. But over time, the bonuses were removed, the base rate was cut, and the number of orders shrank. Eventually, access to shifts disappeared completely, so Ashish left the platform, only to return months later but this time through Mobile World. By January 2023 he was owed €1,800.

Javed, a Master’s student from Pakistan, also worked directly for Wolt before his contract ended. In October 2022, he responded to a Facebook ad that led him to Mobile World. Imran told him he was recruiting for Wolt and assured him that everything—the app, the hours, the payments—would function as before. “The process was exactly the same,” Javed said. “When I asked why Wolt wasn’t doing this directly, I was told, ‘they want to hire a lot of people and use our services.’” Javed began delivering orders in good faith, but like the others, his wages also never came.

By mid-January, dozens of workers had flooded the WhatsApp group Mobile World had set up asking about their missing wages. Some shared that their rents were due. Others said they were owed even more than Sharmila or Ashish. Then came a final message from Imran: Wolt hadn’t paid him, so he wouldn’t be paying them. Any work after January 15th, he said, would be at their own risk. After that, he disappeared.

Some riders, increasingly desperate, attempted to contact Wolt directly through support chats, email, and even by showing up at the company’s office. But their appeals were met with silence or deflection. Wolt insisted it bore no responsibility, referring all complaints back to the subcontractor.

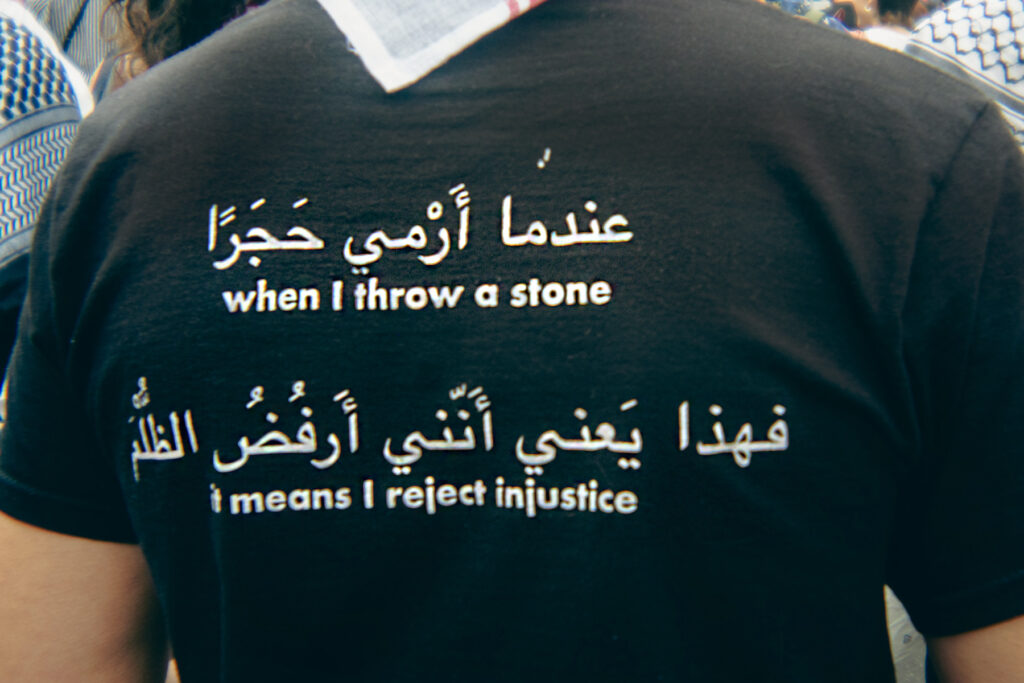

“The scale of the deception didn’t immediately register,” Javed said. “This is such a big company. We still thought the amounts would come because this was Germany.” But Germany, it turns out, is exactly where a multinational can hide behind layers of legal opacity and leave its workers unpaid.

What began as a student job to make ends meet soon turned into a fight for wages, recognition and justice. In June, Sharmila brought her case to Berlin’s labour court. She argued that the subcontracting structure Wolt had built was not a genuine partnership with independent operators, but a deliberate system to avoid labour law while retaining control over the work.

The court disagreed and Sharmila didn’t receive her owed earnings. It found there was insufficient evidence to prove a direct employment relationship with Wolt. The decision underscored how platform companies can design their operations to escape responsibility while still directing every part of the job.

According to workers’ collectives supporting the case, more than 120 couriers have reported similar experiences, with over €100,000 in unpaid wages linked to subcontractors operating under Wolt’s name.

A business model designed for distance

Wolt’s defence, like many digital labour platforms, depends not just on the physical distance between rider and office, but on legal distance. They essentially create a chain of subcontracting that separates them from liability. In the courtroom, lawyers for Wolt insisted the company had nothing to do with Sharmila’s employment. She had signed a contract with IMOQX GmbH (trading as Mobile World), and any failure to pay was theirs to answer for.

But Sharmila’s daily reality told a different story. She received orders through Wolt’s app, responded to Wolt’s support system, and was bound by its shift-booking rules and geofenced delivery zones. When the company had previously employed workers directly, the interface was identical. As were the tasks. What had changed was not the job, only the line on the contract where the employer’s name appeared.

Aju Ghevarghese John, a Berlin-based lawyer and researcher has been supporting many of the riders’ cases. He believes it’s not a bureaucratic accident or loophole, but a designed legal architecture meant to obscure accountability, saying, “The subcontractor model is built to make workers disappear from the platform’s responsibilities.” The couriers, he explained, operate in a legal twilight zone, hired and managed in practice by Wolt, but not recognised in law. “Even when the platform decides everything about the job—where the worker goes, how fast, how much they get paid, the company can say: ‘we are not the employer.’”

Germany’s labour protections, but not for everyone

The case against Wolt exposes more than one bad subcontractor. It lays bare how Germany’s legal framework, while robust on paper, fails to protect those most dependent on it: migrant workers operating on the fringes of formal employment.

Sharmila, Ashish, and Javed weren’t undocumented. Like hundreds of others, they arrived in Germany on student visas or skilled worker pathways—legal, regulated, and vetted. But once inside the country, the system that brought them in left them to navigate a digital labour market with no oversight. “These workers are being brought in through formal schemes,” explains John, “but once they arrive, they’re not integrated into any institutional systems. There is no training or language support, no workplace induction, no orientation to their rights.”

In that vacuum, subcontracting thrives. Fleet partners often charge illegal onboarding fees of up to €500, skim wages, and pay workers in cash. Riders are routinely left without payslips, proper contracts, or any legal documentation of what they’ve earned, making it nearly impossible to file a claim later.

It’s also not just lost wages that riders are burdened with. Equipment used for deliveries—e-bikes, charging kits, thermal bags—is often leased in the rider’s own name. “It’s a system where the platform doesn’t own the equipment, but it’s leased out in the rider’s name,” said John. “So if anything goes wrong, the liability falls entirely on them.”

And when things go wrong, they can go horribly wrong. In at least two cases, faulty lithium battery chargers for the e-bikes sparked fires in workers’ apartments, destroying not only the bikes but also their homes, documents, and belongings. No compensation or support was offered. “The risk is completely shifted onto the workers,” said John. “The company designs the structure, profits from the labour, but the worker is the one who’s legally and financially exposed.”

Paper rights, no reinforcement

Germany has some of the strongest labour protections in Europe, but many of them function more as theoretical safeguards than enforceable rights when applied to migrant gig workers. That’s not because the laws are weak, but because they depend on enforcement mechanisms that barely exist in sectors like food delivery.

For John, the problem isn’t the law, it’s who the law listens to. “Implementation of labour law in Germany is dependent to a large extent on union density,” said John. “In a sector such as this, where there is such low union density, the actual implementation of labour law will also be very minimal.”

And that union density is low for a reason. Many workers in this industry don’t join unions—not out of apathy, but because the work is so precarious. For international students and newly arrived migrants, the job is seen as temporary, a way to survive between semesters or status transitions. Platforms exploit that short-termism to keep workers atomised and disposable.

Without unions, workers lack not just bargaining power, but access to legal advice, grievance channels, and collective visibility. It’s not that riders are outside the law, it’s that the law doesn’t follow them into the app-based gig economy.

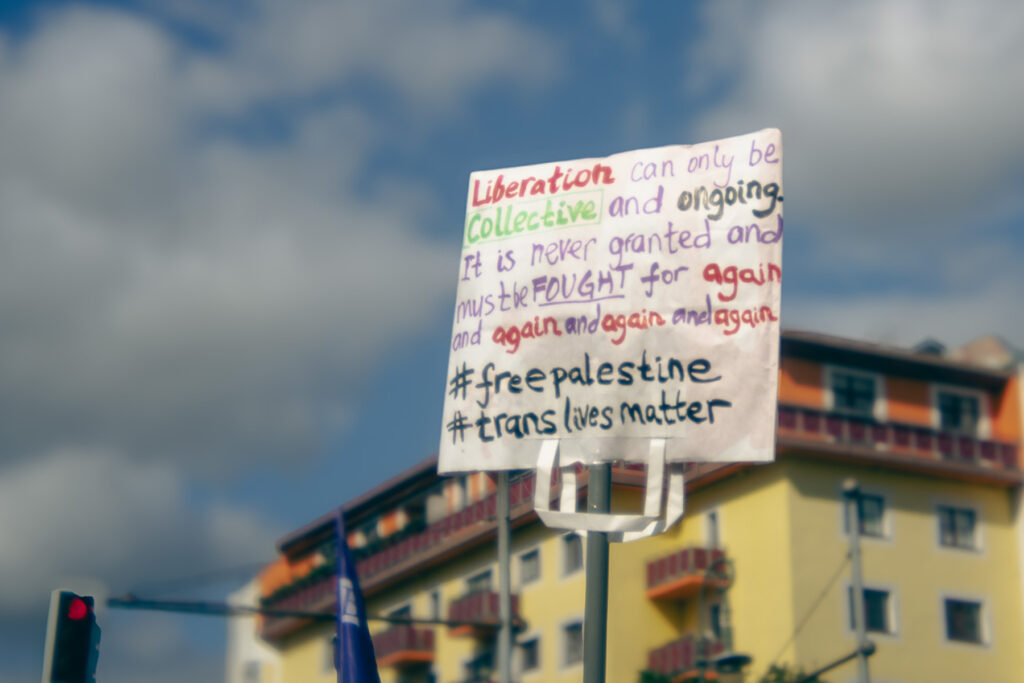

The EU has recognised this gap. In 2026, the Platform Work Directive is due to take effect, introducing a presumption of employment and holding companies jointly liable for abuses by subcontractors. But until then enforcement will depend on what Germany chooses to do with the laws it already has. And right now, the platforms are still a step ahead.

What you can do

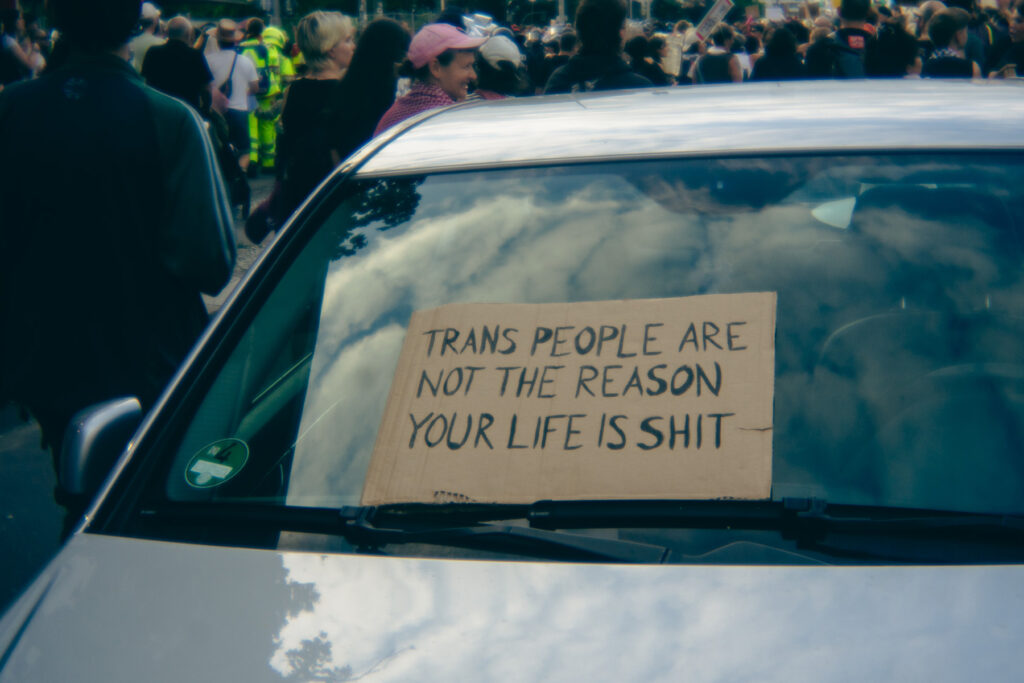

It’s easy to forget that behind every food delivery is a person pedalling through traffic, in rain or snow, to bring a meal they might never afford themselves. And while the apps promise convenience and efficiency to customers, they conceal a system where the people doing the hardest work are also those with the fewest rights.

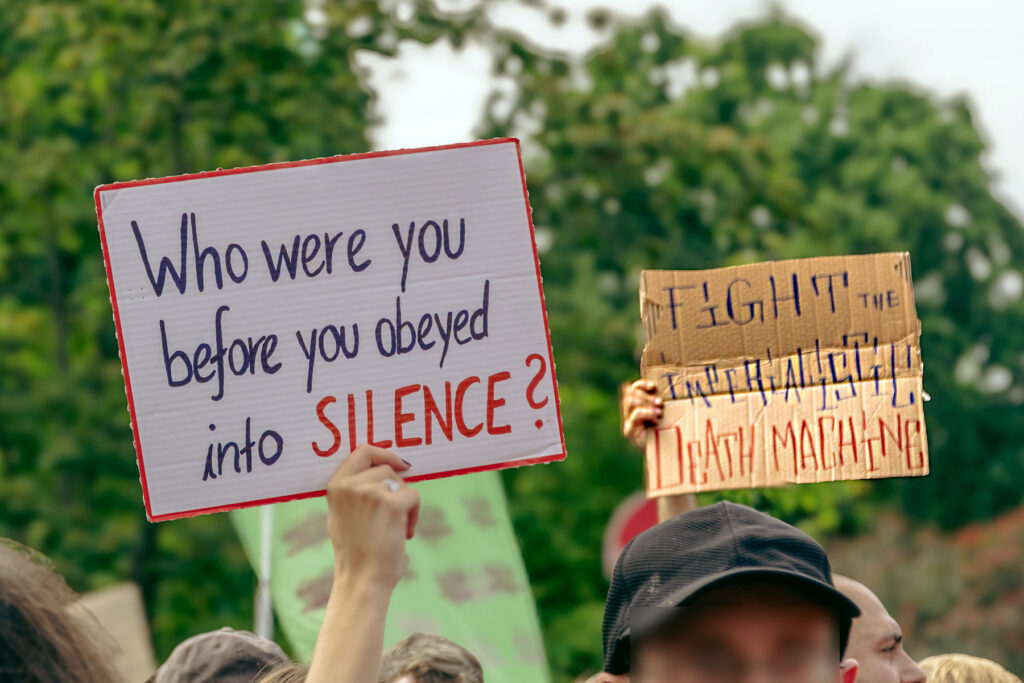

Workers like Sharmila, Ashish and Javed are not anomalies. They represent a growing share of the platform economy, where flexibility often masks exploitation, and where a missed paycheck can mean unpaid rent, mounting debt, or even legal jeopardy. These aren’t problems the algorithm can solve. They require public attention, legal pressure, and solidarity.

It may be tempting to respond with a boycott. But for many riders, these jobs are among the only ones available. International students and migrant workers face restrictions on working hours, language barriers, and unstable residency, all of which limit access to more secure employment. As flawed as the platform economy is, it often remains one of the few entry points into paid work. Boycotting it won’t fix the structure and might only make life harder for those already struggling in it.

But if you are ordering food through one of these platforms, there are ways to support the people delivering it for you:

- Start by tipping in cash when you can. Many riders — especially those working under subcontractors — never receive tips added through the app, as those earnings are often withheld, miscalculated, or quietly siphoned away. A cash tip goes directly into their hands.

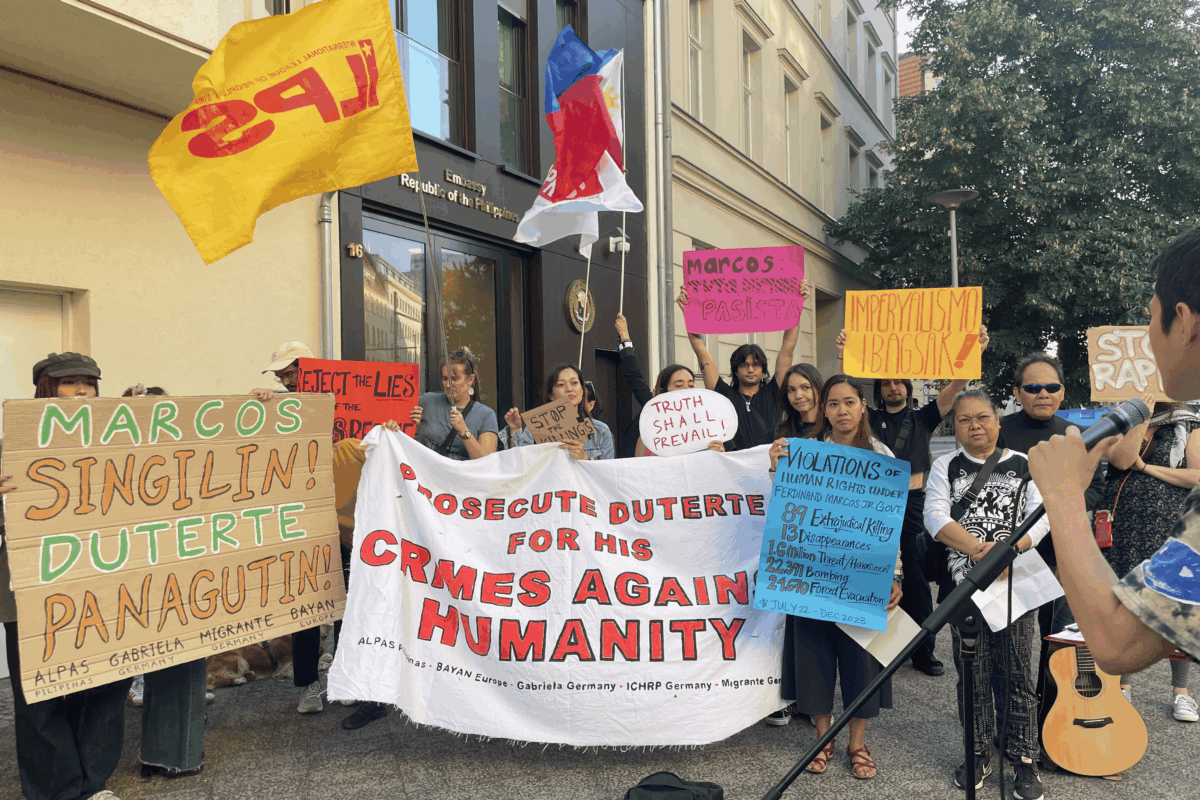

- You can also support the grassroots organisations stepping in where the law has fallen short. Groups like Berlin Workers Support, Lieferando Workers Collective, and the Migrant Workers Solidarity Movement offer legal aid, organise demonstrations, and help riders challenge the systems that keep them invisible. These organisations are often the only shield between precarious workers and the full weight of legal and corporate indifference.

- And perhaps most importantly, talk to the riders themselves. As John put it, “If you want to know what’s really going on, talk to the workers, ask them how they’re being paid, how they got the job, who they report to.” Listening to their experiences cuts through the abstraction and makes the system visible. Then sharing what you learn is a first step in pushing back against the silence these companies rely on.

So, the next time a delivery arrives at your door, consider the labour that made it possible. Not just the ride across town, but the ongoing fight for recognition, dignity and a fair wage that too often remains invisible.

Please note, all the riders’ names mentioned are aliases.