Last November, Dutch Far-right anti-Islam populist Geert Wilders achieved a landslide election win with his PVV party. Far from a sudden shift to the right, this is just the natural response of a society that has been depoliticised and left out in the cold by decades of neoliberal policy. A diagnosis of this ‘’Dutch disease’’:

Nothing out of the ordinary

Geert Wilders and his “Party for Freedom” (Dutch: Partij voor de Vrijheid, or ‘’PVV’’) clinched the Dutch general elections on the 22nd of November, marking the biggest triumph for the infamous Islamophobe. The resounding victory – totalling 23.5% of the vote share – translates to a staggering 37 out of 150 seats in the Dutch House of Representatives. If he can successfully form a coalition government with the other right-wing parties, Wilders looks poised to get closer to government than ever.

News headlines from all over the world expressed ‘’shock’’ at the PVV’s election victory, calling it an ‘’earthquake’’ and ‘’a dramatic result that will stun European politics’’. But we should know this victory is far from surprising. Zooming out even the slightest bit will help us understand PVV’s win.

Geert Wilders is not the first European far-right populist to make a career out of racism, white nationalism, and Islamophobia – nor is he the first to be successful at it. And contrary to what some media outlets portray him as, Wilders is not an ‘’outsider’’.

No humble beginnings

The Geert Wilders we know today is a direct product of the Dutch political establishment. He started his political career in the late 80s with the liberal VVD party – one of the country’s most prominent parties of the last 50 years – and has been a member of parliament for 26 years. Some of his most formative years were spent as a foreign policy assistant to Frits Bolkestein, then-leader of the VVD. Bolkestein is known for having been one of the first Dutch politicians to drive a hard line on immigration, especially from Muslim-majority countries, and Wilders would follow in his mentor’s footsteps.

His work for Bolkestein allowed him to travel to such countries as Jordan, Egypt, Iran and Israel. These trips filled Wilders with distaste and hatred for Islam and Muslim-majority societies on the one hand, and reaffirmed his love for Israel, which he later called ‘’a beacon of freedom and of prosperity, surrounded by Islamic darkness.’’

In 2006, Wilders founded his own party, the Partij voor de Vrijheid (Party for Freedom, or PVV) after splitting off from the VVD, embittered over its acquiescence to Turkey joining the EU. Over the 18-year existence of the PVV, its political programme has largely remained unchanged. Wilders has always campaigned on a toxic combination of white nationalism, xenophobia, climate denial, racism, and anti-Islam rhetoric. His latest election programme foresaw a complete block of new asylum seekers and a ‘’restrictive immigration policy’’. Wilders wants to ban dual citizenship, detain and deport illegal immigrants, and withdraw the temporary residence permits of Syrian refugees, since ‘’parts of Syria are safe.’’ His campaign plans more or less propose a ban on Islamic life, stating: “the Netherlands is not an Islamic country: no Islamic schools, Korans and mosques.“ Wilders is most famous for his virulent statements on Islam, and produced a horrible short-film in 2006 that sought to expose the ‘’inherent violent nature of Islam’’. Speaking about the film, he said:

“Fitna is the last warning to the West. We can choose to pass freedom on to our children or allow our freedom to sink into a multicultural swamp.’’

Despite migration, law & order, and Islam being Wilders’ main themes, his socio-economic politics are perhaps of a different character than many expect. PVV’s most recent election programme foresees tax-cuts on groceries, shorter work weeks, raising minimum wages, lowering energy bills and taking money from ‘’unnecessary’’ climate plans. His ideas have always been much less developed than those of other Dutch parties – many of them are plainly unserious in their ambition – but some of those promises of material betterment have definitely resonated with parts of the Dutch working classes. Even if some of its social politics sound more progressive than the Dutch political centre, the PVV is an extreme-right wing party, and it knows what to use to appeal to broader sections of society.

Though, at the beginning, the PVV did not garner the broader support from the Dutch conservative establishment that it sought. Its main strategist left the party after mere months and claimed that Wilders ‘’had a natural tendency towards fascism’’. His own brother described Wilders’ character as hard-headed and ‘’uncompromising’’. Something extremely odd, but perhaps not entirely unsurprising, then, is the fact that he is the only official member of the PVV. Unlike the rest of the political parties within the Dutch system, the PVV does not operate as a member-based party, granting Wilders complete authority over both the party’s structure and its programme. Despite this, the PVV has been a constant factor in the Dutch political landscape and has been successful to varying degrees over the six elections in which it has participated.

The roots of resentment

The fact that this toxic cocktail of hate has finally led to a big election victory in the Netherlands should not surprise anyone. As internationalist leftists, we know that the efficacy of such rhetoric has been proven time and again in different countries around the world. Perhaps, the persistent image of ‘’the progressive Netherlands’’ put out by the country’s decades of (neo)liberal governments – something most Dutch leftists have never truly believed in – has now definitively been shattered. The Netherlands, with its overly sober and technocratic political culture, may long have seemed immune from such extremism and borderline fascist ideologies, but why would it be?

If anything, it is precisely because of this overly technocratic and borderline emotionless political culture of the Netherlands that far-right, antidemocratic movements are able to flourish. Like in other European contexts, large parts of the Dutch working class are alienated, inflation has hit hard, and the cost of living has gone up massively in recent years. The housing market is in shambles; the average person is unable to buy a house and many struggle to pay rent in Dutch cities, making the Dutch housing market one of the most overpriced in Europe. On top of that, the Netherlands is internationally known as a tax haven for multinational companies, and ranks as one of the most unequal countries in the world in terms of wealth distribution.

For almost 50 years, the country has been ruled by varying coalitions of liberals and Christian democrats. These parties have pushed Calvinist neoliberal narratives of ‘’individual responsibility’’ that have penetrated every corner of Dutch society. Everyday issues such as healthcare, public transport, housing, stagnating salaries, and cost of living have been decontextualised and stripped of their inherently political nature. To top it all off, the Netherlands currently has its longest-serving prime minister ever, VVD’s Mark Rutte. For over 13 years, the robotic technocrat Rutte has overseen various privatisations, enacted austerity measures and further contributed to societal depoliticisation, all while raking in several major scandals.

Pair these facts with the complete abandonment of the working classes by Dutch leftist parties, who over the last decades have shamelessly internalised the dominant neoliberal narratives, and the utter refusal of ‘’the political centre’’ to ostracise the far-right, who instead normalised their rhetoric and talking points, and it becomes clear how Wilders was finally able to win.

Prime Minister Wilders

As this article is published, Geert Wilders is still in coalition talks with the right-wing agrarian BBB party, the liberal VVD party and the Christian democratic NSC party. If they form a coalition, what can we expect of the Netherlands in the next few years?

Without a doubt, this right-wing coalition will further criminalise people who seek asylum and will try to decrease immigration as far as possible. Emboldened by the recent EU agreement which seeks to do just that, Wilders will be able to make work of his decade-old racist plans. He will still have to operate within the skeleton of a liberal democracy, but the societal narrative has been pushed so far to the right that his ideas are more palatable than ever. The previous government even collapsed over VVD’s anti-immigration stance; PM Mark Rutte blocked the possibility of family reunification for refugees, after his party had helped create an ‘’asylum crisis’’ with years of defunding and underfunding agencies responsible for the asylum process. Terrible conditions in shelters ensued, leading to an unprecedented first-time intervention by Doctors Without Borders (MSF) in the Netherlands, and countless media headlines that helped erode public support for welcoming migrants and asylum seekers. The tone was set, migration became a major theme in these latest elections, and Geert Wilders happens to more or less own this issue in Dutch politics. He will continue to do so and seek to implement his campaign promises with the help of his right-wing coalition partners.

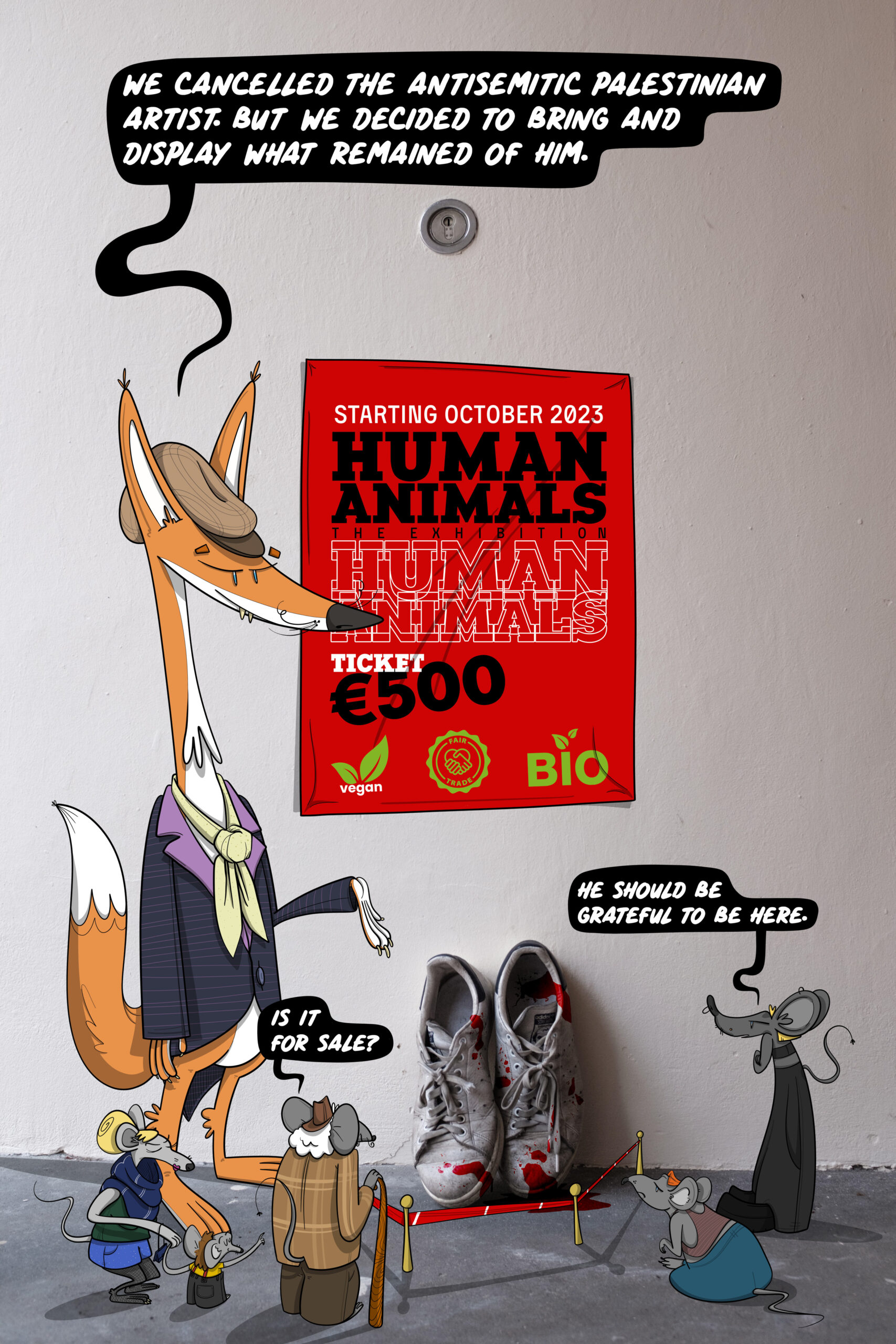

In the short term, this coalition will also continue to cover for Israeli war crimes. The Dutch governments of recent decades have always supported the Israeli occupation and policies of ethnic cleansing, current PM Mark Rutte allegedly even asked his Foreign Ministry to ‘’cover Israeli war crimes’’, but no politician is as big of a cheerleader for Israel as Geert Wilders. Having visited Israel dozens of times, as well as spending two years volunteering in an illegal settlement in the Occupied West Bank as a teenager, Wilders’ support for the Zionist entity is truly boundless. Like Trump did in 2017, Wilders wants the Dutch embassy to be moved from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. His fanatical love for Israel is inextricably linked to his hatred for Islam, in a 2010 speech he said: ‘’The future of the world hinges on Jerusalem. When Jerusalem falls, Athens, Rome, Paris, London and Washington will be next’’. Wilders openly supports the policy of increasing illegal settlements in the Occupied Palestinian West Bank – or ‘’Judea and Samaria’’ as he calls it – which is ‘’an integral part of the Jewish state.’’

Wilders is also notoriously well-connected with European autocrats and far-right actors like Viktor Orbán, Giorgia Meloni, Marine Le Pen, Alice Weidel, Santiago Abascal and Matteo Salvini. Potential prime minister Wilders will no doubt seek closer friendships with these leaders and their countries.

Within the Netherlands, the crises are likely to deepen. A right-wing coalition spearheaded by Geert Wilders and the PVV will not and cannot provide any real answers to the growing alienation of Dutch working classes and the depoliticisation of young people. Geert Wilders’ promises to the average Dutch citizen cannot and will not undo decades of privatisation and the neoliberal erosion of communities. His hateful rhetoric will likely embolden and mobilise extreme right-wing forces to come out of the woodwork and claim their space in the new Netherlands.

While Geert Wilders will not singlehandedly plunge the sober Netherlands into fascism, one thing is clear: his racist plans and anti-Islam rhetoric enjoy the broadest support ever. Although not surprising, his electoral victory is alarming in the context of a pan-European rise of far-right ideologies. It is time for those who so often preach about the values of ‘’liberal democracy’’ to defend it with all their might, and for leftists all over Europe to relentlessly push back against these hateful ideologies. We know the ‘’other’’ is not our enemy.