Hi Théo, thanks for talking to us. Could you start by introducing yourself. Who are you?

I’m Théo, an activist at Berlin Insoumise which is the Berlin Section of the French left radical party La France Insoumise.

We’re a section of 200 registered activists, organise monthly events like conferences and debates, and are active in local campaigns. French people settled abroad have designated MPs, Senators, and local councils to the embassies. Our district consists of Germany and 15 other Central European Countries. I am the joint spokesperson of our section for the district.

This week you organised a meeting which was supposed to take place in Karl Liebknecht Haus, centre of Die Linke. What was the meeting about and who was speaking?

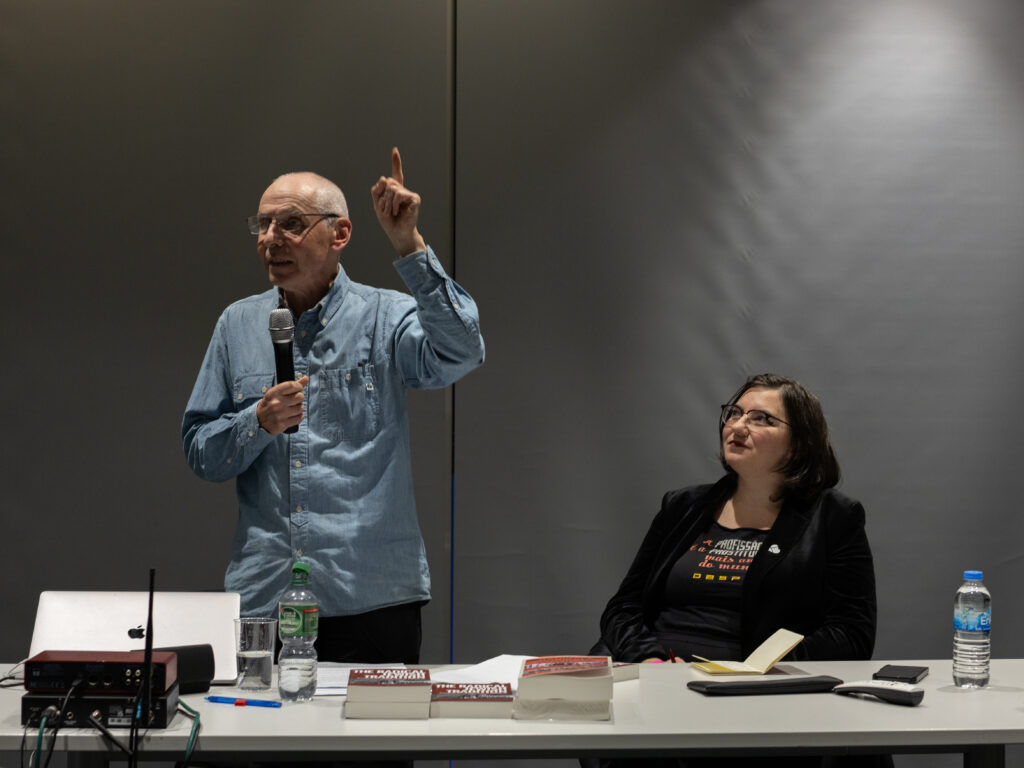

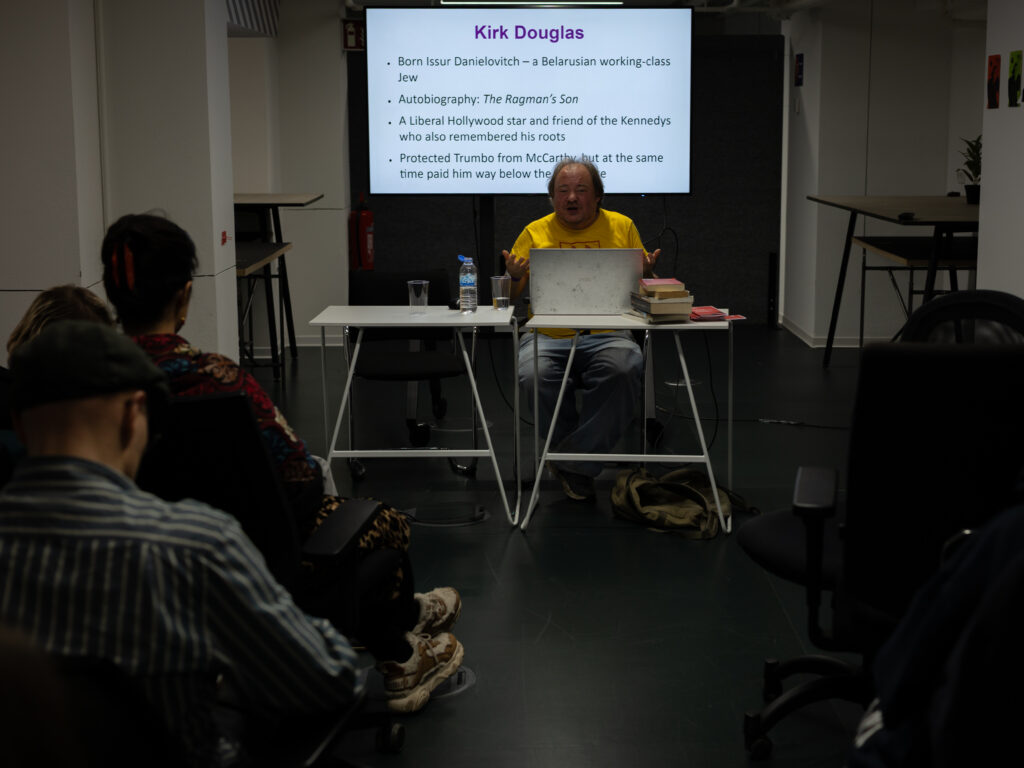

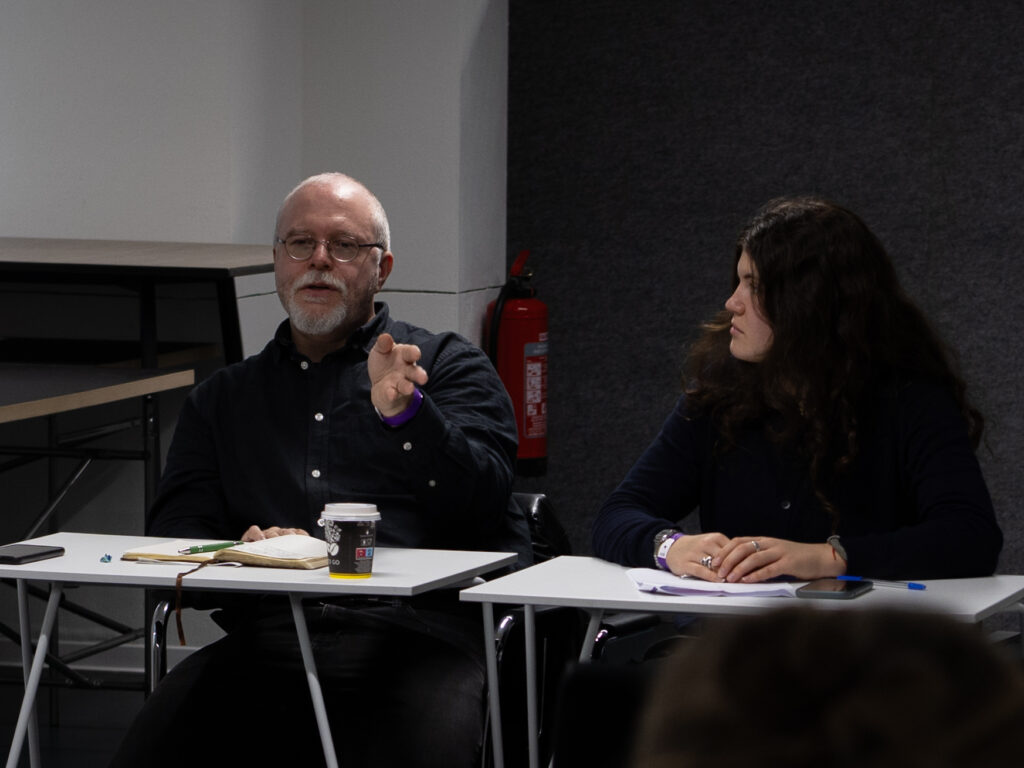

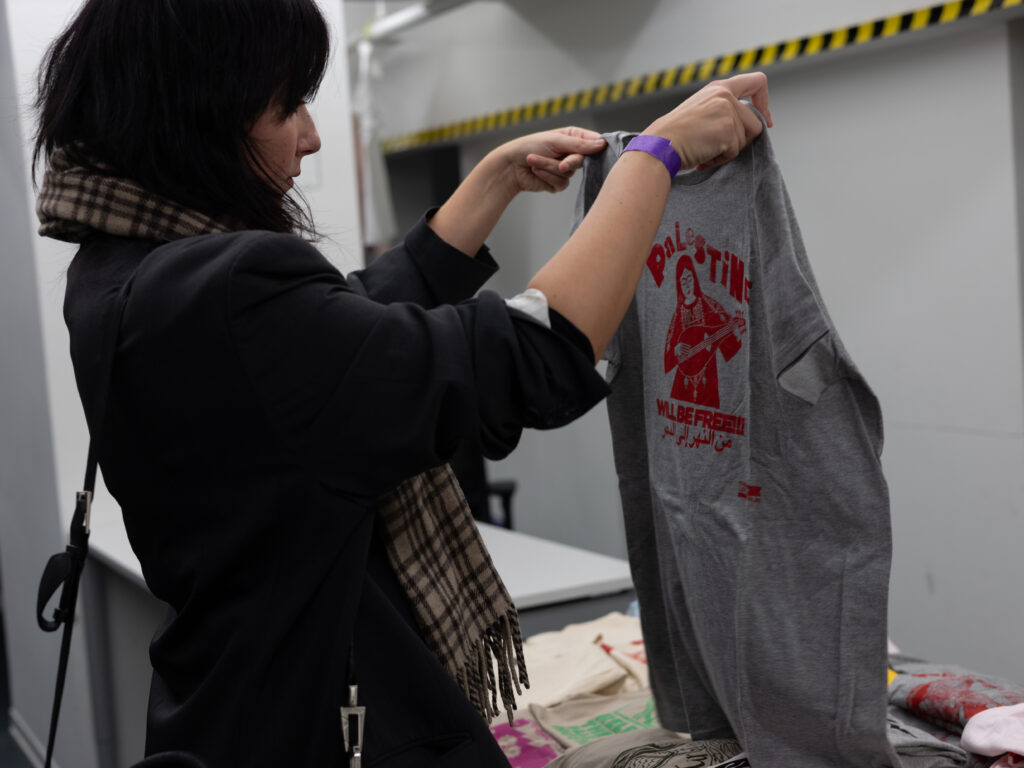

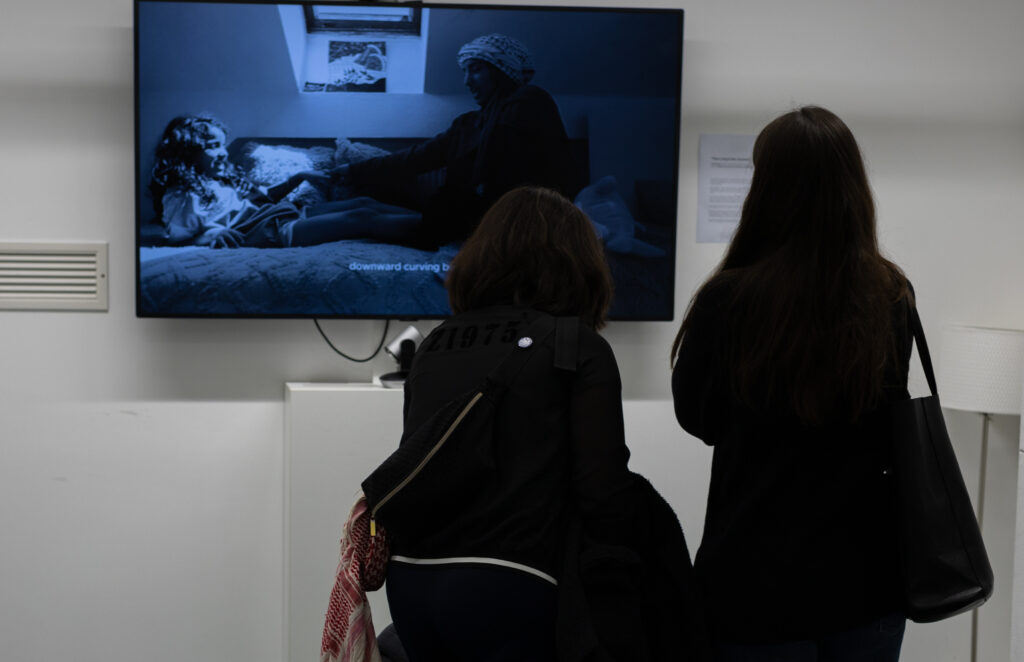

We organised a public meeting about the situation in Gaza. Emma Fourreau (one of our MEPs) contacted us because she’s doing a tour of European universities to meet young activists. We, as the local section of the party, decided to use this as an opportunity to give further visibility about the Gaza situation.

Emma participated in the Global Sumud Flotilla this summer, so we thought this could be a great angle. We gathered in total five people: alongside Emma were Adrien, Leslie, and Mahé who are activists of the flotilla and also tried to breach the blockade this summer. The final speaker was Anissa Eprinchard, a Berlin-based activist who created the account @HomoSwipiens.

We discussed the history of flotillas, what happened during the last one, the situation in Gaza and the state of sanctions against Israel.

And yet at the last minute, Die Linke cancelled your room booking? Why did they cancel and when did you hear about the cancellation?

We have built connections with Die Linke for some years now, and started some months ago to use their logistic support for our events. We had asked them to host our public meeting at their headquarters in Karl-Liebknecht-Haus.

They have conference rooms in house, managed by an “external” institution called Tagungszentrum am Rosa Luxemburg Platz, mostly owned by Die Linke. This would have been our third meeting there since August.

At midday on the day of the meeting, we received an email cancelling our reservation even though the room had been booked for more than 10 days already. The cancellation mail said the following:

“Der kürzlich öffentlich durch Sie bekannt gemachte Inhalt Ihrer Veranstaltung (siehe Screenshots anbei) weicht erheblich von den uns gegenüber im Zusammenhang mit dem Vertragsabschluss gemachten Angaben ab. Zudem sind mittlerweile Protestveranstaltungen vor unserem Tagungszentrum gegen Ihre Veranstaltung in Aussicht gestellt worden. Beide Tatsachen rechtfertigen u.E. ohne Zweifel den Rücktritt vom Vertragsverhältnis.”

(“The content of your event, which you recently made public (see attached screenshots), deviates significantly from the information provided to us for the contract. Furthermore, protests against your event have now been announced in front of our conference centre. In our opinion, both of these facts claearly justify the termination of the contractual relationship.”)

The screenshot that was sent to us as a “proof” was simply our instagram post communicating about the event, where the Freedom Flotilla was mentioned, and pictures of Emma and Anissa, two of our guests.

Die Linke helped organise the demonstration for Gaza on 27th September. Around the same time, party chair Ines Schwerdtner said that the party had learned from the mistakes it had made by not joining the Palestine movement earlier. Do you think they have learned from their mistakes?

Unfortunately I don’t think so. The email cancelling our event directly came from the Geschäftsführer of the Tagungszentrum, Mathias Höhn, even though we had previously been in touch with other people from their organisation. Mathias Höhn is directly involved in Die Linke and has occupied various party positions.

We see and deeply condemn the fact that to this day, it is still impossible to talk about the Palestinian genocide in Gaza in Germany.

Ferat Koçak, Abgeordnete of Die Linke in Neukölln, tried to intervene in our favour and called directly Herr Höhn, even offering to host our conference under his name, without success. In a statement, Ferat offered support: “It is serious that our sister party La France Insoumise, and in particular MEP Emma Fourreau, has been refused the use of our premises. We need spaces to discuss Palestine”.

I would add that this event was also not organised by an organisation that is absolutely foreign to Die Linke. We’ve been working together for a long time, and sit in the same group at the European Parliament. They basically cancelled an event with one of their comrades and colleagues, Emma Fourreau.

How does this affect the relationship between Berlin Insoumise and Die Linke? At last year’s Left Berlin Summer Camp, Asma Rharmaoui-Claquin (co-speaker of La France Insoumise in this district and parliamentary condidate in the last two elections) said that she couldn’t envisage working with the party because of it’s stance on Palestine. Things seem to have improved since then, and people like Ferat are playing an important role, but has enough changed for you to continue to collaborate?

To clarify Asma’s position, we had stopped working with Die Linke because of their lack of support for the Palestinian cause. With it starting to move internally, we started to collaborate more.

I’ll just speak in my name on your question because we have not discussed it yet with the Berlin comrades. It does come with great disappointment. However, I observe a huge gap between the activists of Die Linke and the position of the party in general.

I meet comrades of various Die Linke sections on a monthly basis to work on digital tools for left radical organisations, and see some openness about the Palestinian topic. We also got support from comrades from Neukölln and Tempelhof Schöneberg. On the day of the meeting, Emma met comrades from Die Linke Jugend who disapproved of the decision to cancel our meeting.

I think it is essential to support comrades there that share our positions and help them move the lines of their party

There are elections in Berlin next year, and there is a reasonable chance of the next Berlin mayor being from Die Linke. As a result, pro-Palestine motions have been withdrawn from conferences in the name of “party unity”. What do you think of this strategy ?

I think that this is a moral failure and a political mistake. There have been 200 breaches of the “ceasefire” in the last month, and people are still being killed in Gaza, while Europe watches without taking any action. The CDU wants to restart delivering weapons to Israel. This genocide is far from over, and we need to stand against it.

Berlin is a city with a left heart and a mixed population. This will not benefit Die Linke.

We are conducting this interview on Thursday 19th November. In 2 days’ time, Palestinian activist Ramsis Kilani is appealing his expulsion from Die Linke. Has Berlin Insoumise discussed this case and what do you think?

We have not discussed his case unfortunately, and I’m afraid I don’t know everything about his exclusion.

Nonetheless, I can only pay tribute to his bravery for deciding to fight his internal party structures and not quit in silence. I hope he wins this appeal and manages to move party lines internally. He stands for a single, secular state, with guaranteed rights for every citizen, of every religion, which is also my personal position.

What’s next for Berlin Insoumise? And if people read this interview and want to get more involved how can they contact you?

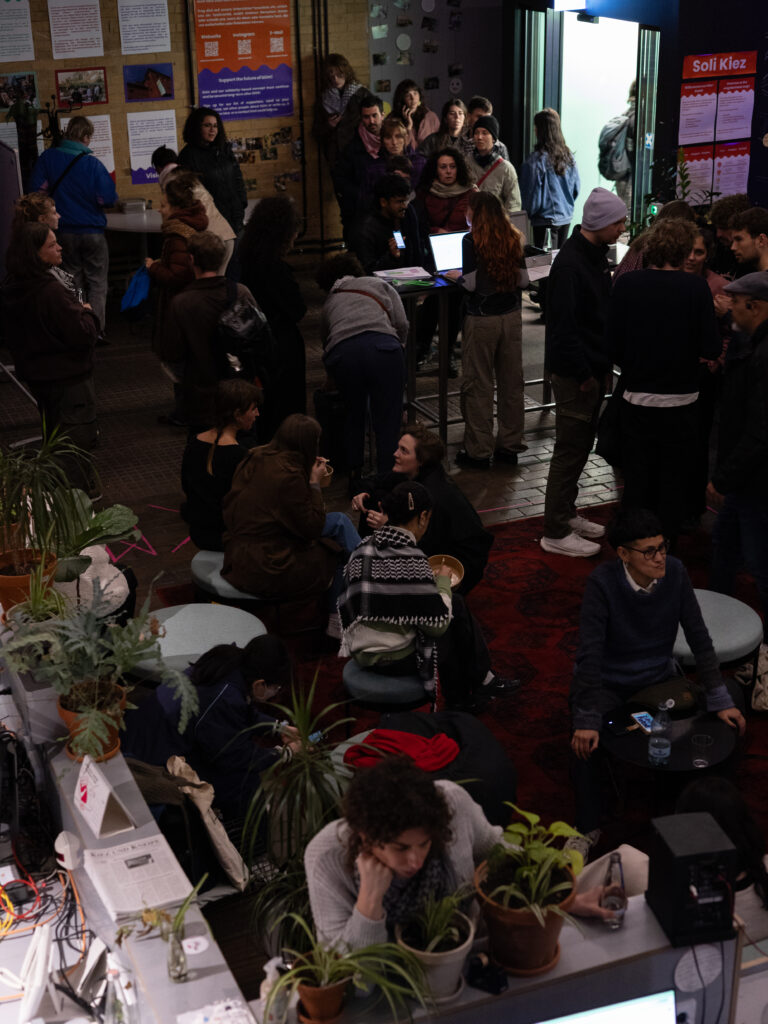

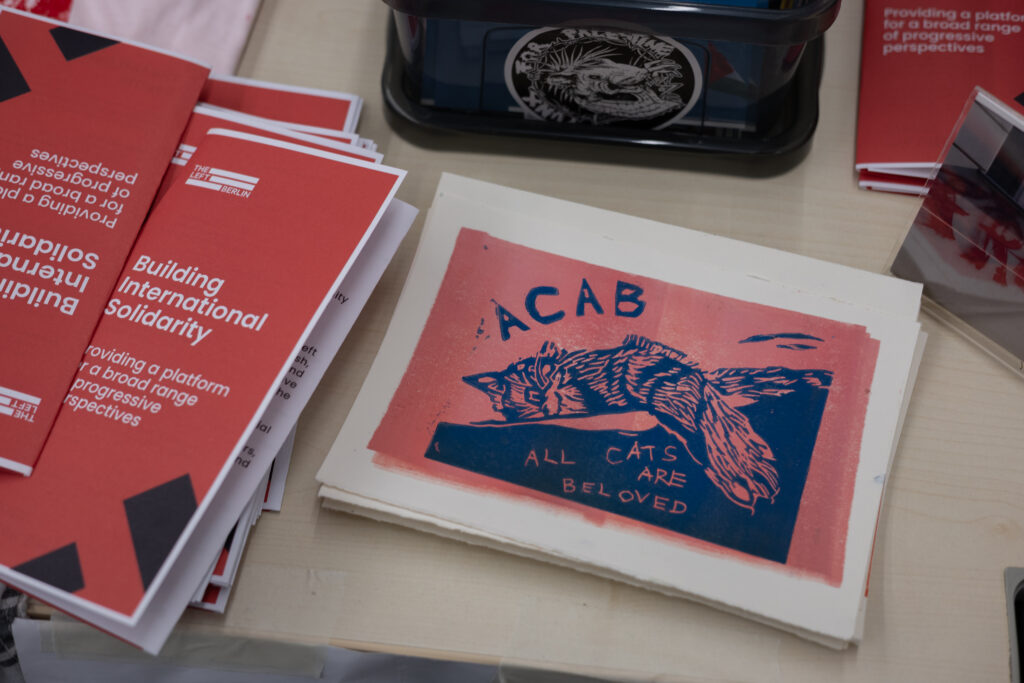

First of all, I’d like to thank comrades from other organisations who helped us find a plan B in 2 hours and maintain our event. This proves how important and effective it is for all our radical organisations to stay connected and help each other.

We will keep on doing what we do best: organise events and actions! Most of them are in French but some are also bilingual in French and German.

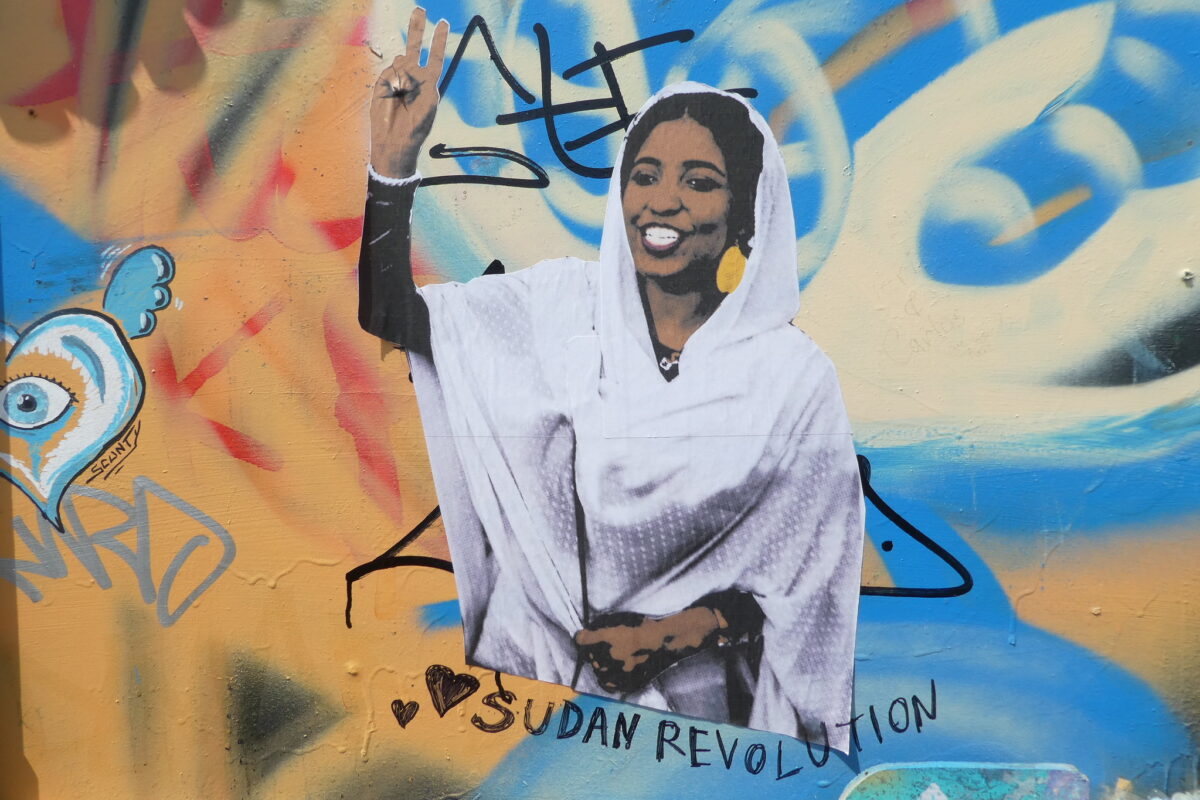

Funnily enough, the next one is also organised with an organisation of Die Linke: we are organising a conference about the situation and massacres in Sudan with Aurélien Taché, French MP of LFI and Roman Deckert (Sudan expert for the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung).

On January 3rd, we are hosting a conference about our hopes for the 6th French constitution with Pierre-Yves Cadalen, French MP for Brest.

We are also getting ready for our next campaign in June, for the councils to the French embassies.

People can reach us any time on Instagram @BerlinInsoumise or by email contact@berlin-insoumise.org.

Or just come to an event 🙂

Is there anything you’d like to say that we haven’t covered already?

We’ve been consistently supporting the rights of Palestinian lives in France when all other left parties were calling us antisemites. We’re on the right side of history and the whole French Left has finally joined us—too late—after 2 years.

I hope for the same for Germany, and wish success to the comrades in German organisations that are fighting for Palestine.

A representative from Berlin Insoumise will be speaking at the rally in support of Ramsis Kilani’s appeal against his expulsion from Die Linke, on Saturday, 22nd November at 11.30am outside Karl Liebknecht Haus.