Two months into his term, Romania’s new president, Nicușor Dan, has chosen his first hill to die on. No, it’s not an ardent fight against the government’s catastrophic austerity measures, even though these contradict Dan’s explicit campaign promise that VAT would not be raised. Dan has decided to make his first public and legal presidential intervention by repeatedly challenging a new law project that would increase penalties for promoting and distributing fascist and far-right materials.

This might come as some surprise. In May, Dan’s victory in the Romanian presidential elections hit international news as a much-needed sign that the European right-wing surge could be stalled. After an eventful electoral season decided through lawfare, the independent mayor of Bucharest appeared as a centrist, liberal, pro-European savior who stopped the fall of yet another country to extremist rule. Dan has now refused to promulgate a law against fascism voted in by Parliament — first by sending it to the Constitutional Court; and upon his challenge being rejected by the Court, by announcing that he would send it back to Parliament for redrafting.

This showcase of presidential stubbornness is, however, not shocking. Although Dan defeated a far-right candidate in the presidential elections, his personal history and political profile are clearly conservative. More importantly, his challenges to the law fit into the mainstream of Romanian memory politics, a mainstream that legitimizes far-right opinions and historical figures under the justification of anti-communism.

The Legion

Dan’s fig leaf throughout this scandal has been his insistence that he is not willing to accept fascist points of view, and that his concern is rather with the lack of concrete definitions in the law, bringing up a specific example in a public statement about the issue:

“In the town of Făgăraș [Dan’s hometown] there is a small association dealing with the promotion of the [anti-communist] Resistance in the Făgăraș Mountains […]. Among the members of the Resistance in the Făgăraș Mountains are a few persons who in their past had been part of the legionary movement. The question is: does this association have a legionary character or not? Because the law does not tell us. And, if it does have a legionary character, should these people go to jail or not? Because the law tells us that, if you set up an association with a legionary character, you have to go to jail. I think not, I think that it is legitimate to promote the anti-communist Resistance in the Făgăraș Mountains.”

Dan’s accusation that the law does not clearly spell out what a “legionary character” is can immediately be disproved by looking at the text itself. Part of the justification put forth by the MP who proposed the law is that it would close loopholes in the existing legislation with “a better definition of some notions,” including “legionary.” And the definition offered in the draft law is nothing if not concrete, referring to membership in the “fascist organization in Romania that was active in the period 1927-1941 under the names ‘The Legion of the Archangel Michael,’ ‘The Iron Guard,’ and the ‘Everything for the Country Party.’”

The Legion, the main far-right organized movement in interwar Romania, is at the center of Romanian memory politics and polemics. A nationalist, antisemitic, Christian Orthodox movement, the Legion reached mass membership among peasants and students under the charismatic leadership of “Captain” Corneliu Zelea Codreanu. Legionnaires got together in work camps where they built local civil and religious infrastructure. These camps and local “nests” also promoted Orthodox mysticism and paramilitary organizing, which ultimately manifested in high-profile political assassinations carried out by fanatic legionnaires.

Scared by their growing power and electoral success, the dictatorial King Charles II cracked down on legionary organizing and had Codreanu assassinated under the cover of a failed attempt to escape arrest. Charles, however, was himself forced out of the country by General (later Marshal) Ion Antonescu. Antonescu went on to become Romania’s military dictator during the country’s participation in WWII on the side of the Axis powers, allying himself with the Legion to proclaim a National Legionary State.

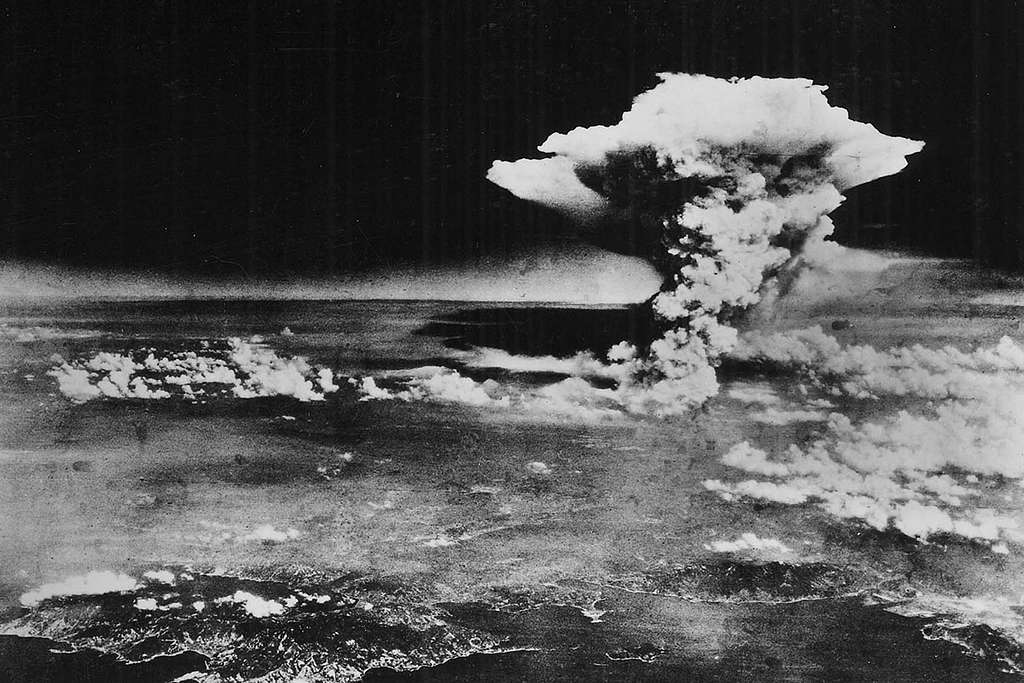

This alliance was however short-lived, as tensions between Antonescu and the Legion came to a head with the latter attempting a coup in January 1941. The legionary rebellion quickly became a two-day pogrom that killed 125 Jews in Bucharest. After the rebellion was quashed by the army, the Legion’s leadership fled the country and thousands of its members were imprisoned. Those legionnaires that remained free continued to participate in Romania’s antisemitic atrocities, such as the June 1941 Iași pogrom.

Although defeated and disbanded, legionnaires and the legionary ideology continued to act and to capture the Romanian imagination. Already based on a fascist-cum-Orthodox death cult, legionnaires embraced their imprisonment as a form of martyrdom. Others took refuge in monastic life, as monks or lay inhabitants of sympathetic monasteries.

Their true glorification, however, began after the 1944 coup, when Romania turned against Germany, and gradually came under communist control. Many legionnaires took refuge in the mountains and organized into armed groups, fighting against the Red Army, and later against the forces of the new Romanian communist state. Anti-communist resistance was extinguished by the early 1960s, but accusations of legionary membership or sympathies became one of the main justifications for political imprisonment in Romania throughout the communist period.

Even so, the dividing line between communist and legionnaire is not as clear as it might seem. The communist regime, for instance, instrumentalized imprisoned legionnaires, co-opting them as torturers in the infamous prison “re-education” programs of the 1950s. And even as the Legion remained the regime’s scarecrow, Romanian communism itself became more and more nationalist, in ways that closely resembled interwar fascist discourse.

Saints and heroes

The Legion’s post-1989 legacy is marked by this paradox. On the one hand, Nicolae Ceaușescu’s nationalist communist party produced the ideological framework and even the members of many far-right parties and organizations of the 1990s and the 2000s. Communist elites who became post-communist politicians overnight continued calling their adversaries “legionnaires”, as for instance during the violently repressed student protests of the early 1990s. They had little interest in giving this floating signifier any substantive content, or in risking their own nationalism being interrogated by a real inquiry into the Legion.

On the other hand, the Romanian search for non- and anti-communist historical narratives settled on a romanticized interwar period as the last milestone of a European trajectory interrupted by the external, Oriental imposition of communism. This left little space for a critical engagement with the far-right movements of Romania in the 1930s, or with the sympathies that many of the cultural elites—now also recovered as the authentic expression of Romanian values before and beyond communism—expressed for these movements.

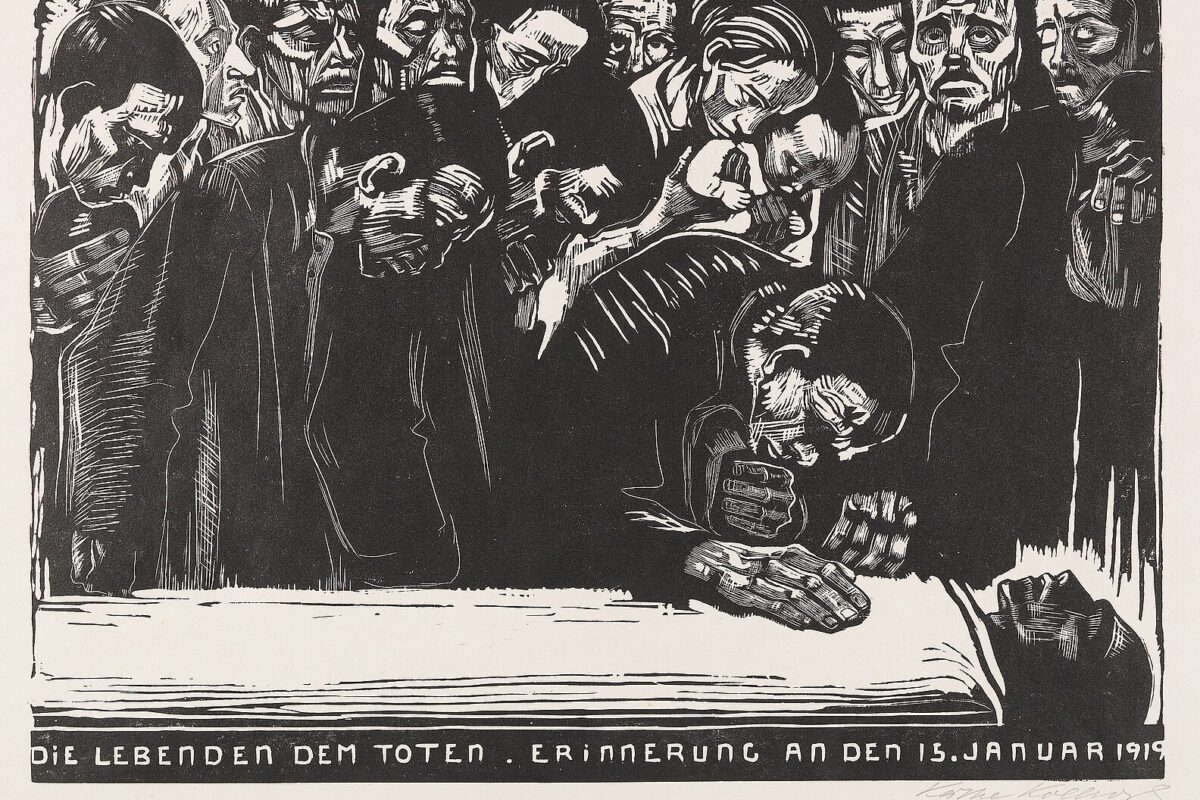

The lack of a reckoning with the Legion’s historical role and legacy allowed a different type of memorialization to develop and become mainstream. Former legionnaires, or their descendants and sympathizers, latched onto the communist condemnation of the Legion to paint an image of heroic martyrs. The (auto)biographies of jailed legionnaires became narratives of Orthodox suffering at the hands of an atheist (judeo-)bolshevism, peppered with stories of suffering, self-sacrifice, and saintly revelation.

The idea of “prison saints” took its place as a central trope in stories of repression and violence. All of this happened with the active participation of the Romanian Orthodox Church, where (former) legionnaires have played important roles in its monastic branch, the main source of leadership within the Church. Through the Church, the “saints” moniker became literal, as several legionnaires were recently canonized.

Outside of prisons and monasteries, the main vector for the memorialization of legionnaires has been their resistance against communism. The participants in the resistance had diverse motivations. While many of them were indeed legionnaires fighting out of conviction, or to avoid prison, others were members of other political parties, were royalists, or were simply resisting nationalization and collectivization. Regardless, the armed groups that took refuge in the mountains have gained mythical status in Romania, with their image folding into romantic narratives of bandits or hajduks.

Legion sympathizers, however, have managed to take over the memory of communist oppression and anti-communist struggle, claiming, for instance, that 75% of all political prisoners were legionnaires. They have used the resistance—an absolute force for good in Romanian historiography—to whitewash fascist holdouts as heroic underdogs. At the same time, the centrality of legionnaires in narratives of resistance turns anti-communism itself into a legionary action, infusing statements of support for the anti-communist resistance with implicit apologia for the Legion.

Electoral triggers

This is where Dan’s intervention comes in. Although he does not explicitly name it, the association that the President most likely is referring to when questioning the new law is the “Ion Gavrilă Ogoranu” Foundation. Ogoranu, a native of the Făgăraș area, was the leader of a legionnaire youth group, arrested in 1941. When the communists took power, he led a relatively long-lived armed resistance group and gained fame by evading arrest for decades.

The foundation, set up after his death, is far from the local initiative that Dan tries to present it as, but rather a mainstay of national debates on memory culture and the legacy of legionarism. Its secretary, Florin Dobrescu, was present at parliamentary debates over the new law project; and the Foundation filed its own complaint about the law project to the Romanian Ombudsman and to the Constitutional Court. Dobrescu also publicly thanked Dan for his intervention, calling him an “authentic democrat” and a “president of all Romanians”.

The dilemma that Dan presents to the public is whether this foundation, honoring an anti-communist hero, has a “legionary character” only because that same hero happens to have been a member of the Legion. Rather than musing over what “character” is, however, the dilemma can very easily be resolved by looking at the activities of the Foundation’s secretary. Dobrescu is currently under investigation for organizing memorial services for Corneliu Zelea Codreanu, who, having died 10 years before Romania became a communist republic, could not have been an anti-communist fighter. Dobrescu not only organized the services, but also officiated parts of them, leading attendees into performing Nazi salutes.

These services have been taking place for years, but they only received public attention in 2024. While far-right groups, movements, and publications have been growing since the 1990s, it took the shock of two far-right politicians’ near victories in the recent presidential elections to trigger the Romanian state into action. When Călin Georgescu took everyone by surprise and won the first round of the elections in November, journalists uncovered his vast connections to neo-legionary work camps and memorial associations, including the Ogoranu Foundation.

After Georgescu’s victory was invalidated by the Romanian Constitutional Court due to alleged Russian interference, and Georgescu was banned from participating in the re-run, his place was taken by another far-right candidate, George Simion—who qualified for the run-off, only to lose to Nicușor Dan. A more established politician than Georgescu, Simion was already known for his far-right positions, but investigations also uncovered that he was embedded into neo-legionary networks, including monasteries and associations. Among them: the Ogoranu Foundation.

The growing strength and influence of Legion sympathizers had been going largely unnoticed or accepted by Romanian authorities. The new legislative project was meant to strengthen the application of the existing laws criminalizing the propagation of legionary and fascist materials, and the denial of the Holocaust or of war crimes. Between the years 2022–2024—a period of intense organizing leading to the last elections—no person was prosecuted for Legion sympathies. Among those who slipped through the cracks was Georgescu himself, whose 2020 declaration that Ion Antonescu and Corneliu Zelea Codreanu were “national heroes” led to an investigation, in which the charges were ultimately dropped. It took Georgescu almost becoming president for him to be prosecuted for propagating fascist ideas.

Dan now seems to have hit the ideological and legal brakes on a long-awaited police crackdown against the far-right, a crackdown legitimated by his own electoral victory. This is not, however, a deviation from the President’s own political orientation. Most famously, Dan left the Save Romania Union—the party that he co-founded—over their embrace of same-sex marriage, with which he disagrees. This attitude goes back to 2000, when, before he became an activist or politician, he published an article declaring himself a nationalist and condemning “homosexual behavior” in public as damaging “traditional values and thus my collective, legitimate identity.”

More directly relevant is Dan’s refusal to rename Mircea Vulcănescu Street when he was Mayor of Bucharest. The street bears the name of a Romanian intellectual and subsecretary of state in the Antonescu government who was condemned as a war criminal in the post-WWII communist trials. After the Elie Wiesel Institute for the Study of the Holocaust got a court to order the renaming of the street, the city government—led by Dan—announced that it would appeal the decision, following concerted media and public campaigns coordinated by online far-right groups.

Dan’s centrism, like all centrisms, leans right. His problems with fascism seem to be vague accusations of violence and extremism rather than its more substantive contents. In a December 2024 interview, when asked whether the Legion was “good” for Romania, he condemned its use of political assassinations, but had to be repeatedly prompted by the interviewer to finally also condemn its antisemitism. And his recent decision to challenge a law approved by both the Parliament and the Constitutional Court echoes his actions as mayor. In both cases, he clearly sees his own judgments as superior to those of others. As he declared after his constitutional challenge was rejected, he is still of the “opinion” that more than half of the new project is “unconstitutional, even if the Constitutional Court said something else”, continuing to make a political intervention under the guise of a legalistic one.

Memory politics

Does Dan personally hold right-wing convictions? Yes, he has told us as much, and there is no reason to ignore him. Convictions are not the only driver of his vehement intervention against the law, however. The President’s position within Romanian memory culture is a key aspect of his own legitimacy as a leader and politician.

Although his electoral victory meant the momentary defeat of the far-right, it was far from being an antifascist victory. Dan won the election as an anti-communist, rallying against social services, public spending, civil servants, and state-owned companies. His appeal as an activist-turned-politician was built on his claim to dismantle the corruption and clientelism that have plagued Romania due to its inability to shake off its communist past.

Amidst Dan’s defense of fascist anti-communist resistors, a poll was published showing that over 50% of respondents considered communism to have been a good thing for Romania, and over 66% considered Ceaușescu to have been a good leader. Romanian commentators and politicians responded by raising a paranoid moral panic. The director of the institute running the poll attributed the results to “Russia’s hybrid war”. The president of the state’s Institute for the Investigation of the Crimes of Communism once again called for a law that bans communist symbols. Dan himself used the poll results to rally against manipulation and disinformation, stressing how “fragile our memory culture is”, and the “duty to learn from the past”.

Dan cannot actively condemn the Legion without also undermining his own legitimation in a rabidly and unilaterally anti-communist memory politics. But anti-communism as both common sense and as state policy has been the main legitimating ideology of the far-right today. Just as a Ukrainian Nazi-collaborator veteran was applauded in Canadian Parliament because he was anti-Soviet (today read as anti-Russian), so too are Romanian Legionnaires memorialized as having been on the right side of history.

This is also where the usefulness of legal solutions hits its limits. Yes, it is good to protect those vulnerable to far-right speech and attacks, and it is good to have the state break down organized neo-legionary groups. But the fact that so much Legion sympathy has gone unprosecuted is not due to the weaknesses of one specific law, but to the fact that investigators and lawmakers are themselves part of the anti-communist apparatus that is right-wing, almost by definition. After all, another law, passed in 2017 by Romanian Parliament, establishes a memorial day for “martyrs in communist prisons” using language taken directly from neo-legionary propaganda.

Even commentators who claim to appreciate the effort to fight against the far-right decry that communist speech is not covered, either in this law or in another—a conflation that is inaccurate and harmful. And as the recent Czech example shows, the outright banning of communist symbols and messaging is always around the corner in Eastern Europe. While a true effort to learn from the experiences of communist states involves dealing with their violence and failures, the total erasure and demonization that has been the mainstream so far has only led to deadly capitalism and to the rise of the far-right.

And this is exactly what is happening in Romania right now. Dan tries to play the role, as one journalist puts it, of an anti-communist “enlightened nationalist” who can assuage the cultural grievances that Georgescu and Simion rode on to almost take power, without falling into extremism. At the same time, the government he legitimated and put in power is enacting austerity measures that will deepen the inequalities and divisions in Romania to new lows—all the while increasing military spending, including on new defense contracts with Israel.

Another recent poll shows that the Alliance for the Union of Romanians, Simion’s far-right party, has strengthened its lead over Dan. It might seem ironic that the same social and economic conditions that led Romanians toward accepting communism as a good thing for the country also led them towards voting for a far-right that draws its legitimacy from anti-communist resistance. But Romanian communism has been emptied of its social policies and achievements, of its large-scale programs of progress and construction, as projects of a leftist, socialist vision. All that has been left of its culture within the Romanian public consciousness is its nationalism, its sovereigntism, its personalist rule: converging with the narrative of the contemporary far-right.

Romanians do not want the lack of freedom that marked their pre-1989 existence, but the security and the welfare that they had before capitalism and neoliberalism. As the center actively guts these services to adapt to capitalist forces, and as it also hollows out all memories of communism, the only place to invest these hopes is the far-right. Unless a different, positive project of well-being arises, uniting Romania’s past with Romania’s hopes for the future, the far-right will continue to monopolize the country’s political imagination.