Editor’s Note: This article is a response to ‘Is This Fascism? Not Yet’ by Nathaniel Flakin. Read Nathaniel’s side here.

”First they came..”. is one of the most quoted poems expressing the need to fight fascism and injustice. It was written no earlier than 1946, only after Nazi defeat, by German pastor Martin Niemöller who was a Nazi supporter and an antisemite:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

The poem highlights that fascism doesn’t suddenly arrive—it happens in steps and that those enabling it recognize it after its total success or perhaps only after its crushing failure.

When I read the article entitled “Is This Fascism? Not Yet” by Nathaniel Flakin, I was dumbfounded by the early conclusion, ‘‘Not Yet’’. Many I spoke to who are in constant confrontation with the German state vehemently disagreed as well. The ‘‘Not Yet’’ part of the article’s title seems to apply only to some of the people in the ‘‘Then they came for…” parts of the poem. It is as though we’re midway through the poem but the people at the outset still don’t seem to recognize it.

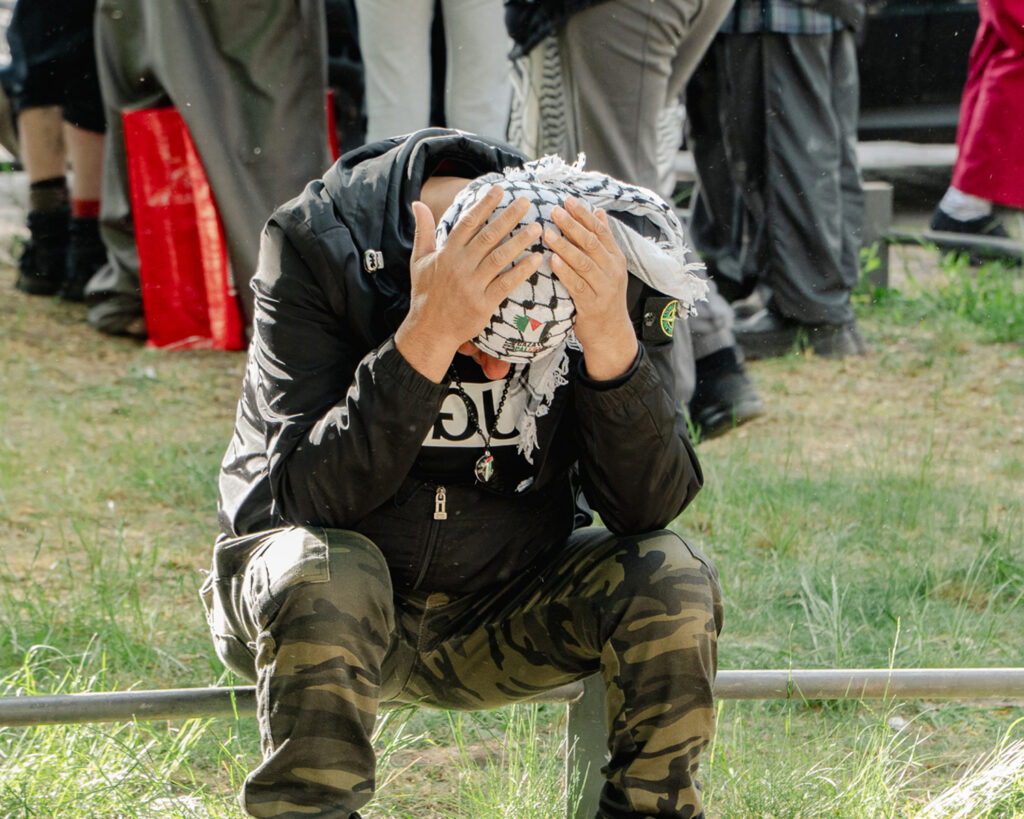

People use the term fascism because that’s how life feels here in Germany. For many, it comes from their experiences that match the popular imaginary of what fascism is.

It would be a mistake to undermine that popular imaginary. Indeed there can be no doubt, even to an external observer, that Germany is continuing on that path. The word ‘‘fascism’’ has been established as an incontrovertible evil, and people use it to warn about the trajectory of the continued inaction in the face of illiberal performative democracies or the support of ‘‘fascist’’ measures and rhetoric—even in the absence of blatantly fascist parties.

Throughout history, the making of a fascist regime is rarely labeled as fascism. The naming and framing of a regime as fascist becomes recognizable after the success of their policies, which is the same fundamental error in Flakin’s piece.

In Germany today, we may not have the dictatorship and totalitarianism that the term fascism is historically linked to, but we have a great majority of the accompanying symptoms of fascism, which include support for a single view on some topics, demonization of minorities, glorification of violence, weak institutions, and rampant racism. But what’s more, we have a government building more repressive tools. These are conditions not dissimilar to Germany leading up to 1932.

Fascism is not some remote historical narrative. It continues to manifest itself in different ways adapting to the context in which it seeks to rise. Its newer forms have similar effects on people. Indeed, perhaps this reputation of evil is one of the reasons why fascism today isn’t pursued as explicitly as it was before and is shrouded by electoral shams and diversions only to prove that it is not that evil term ‘‘fascism’’.

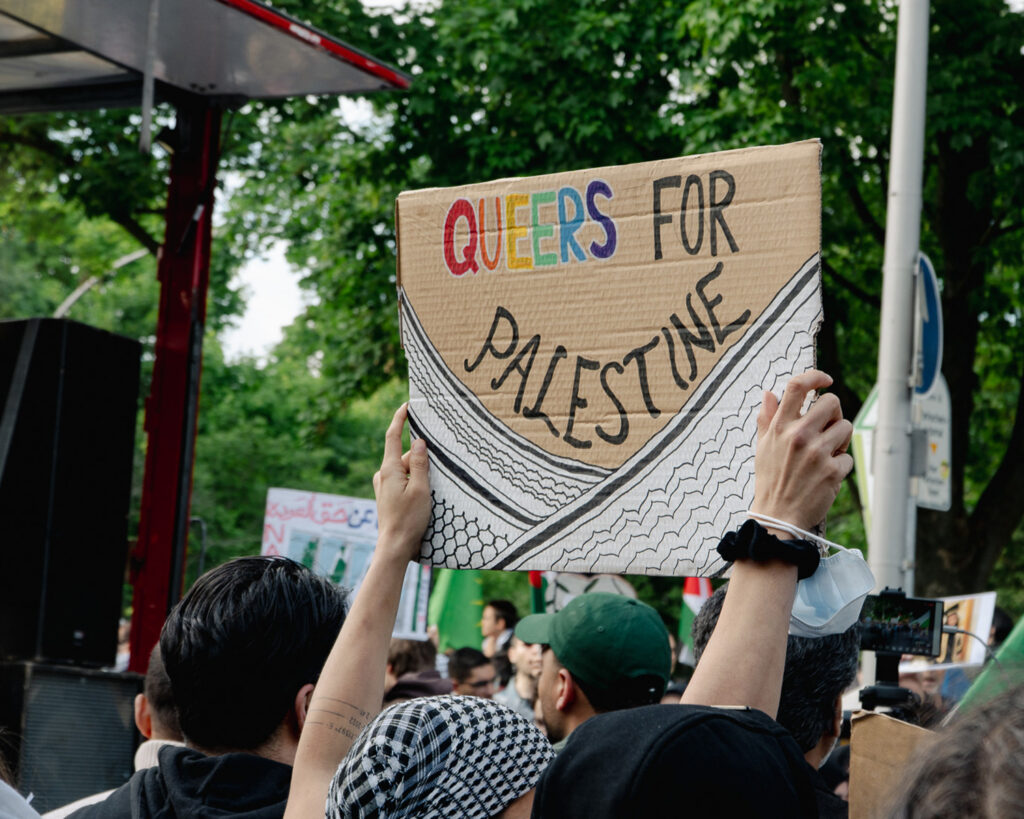

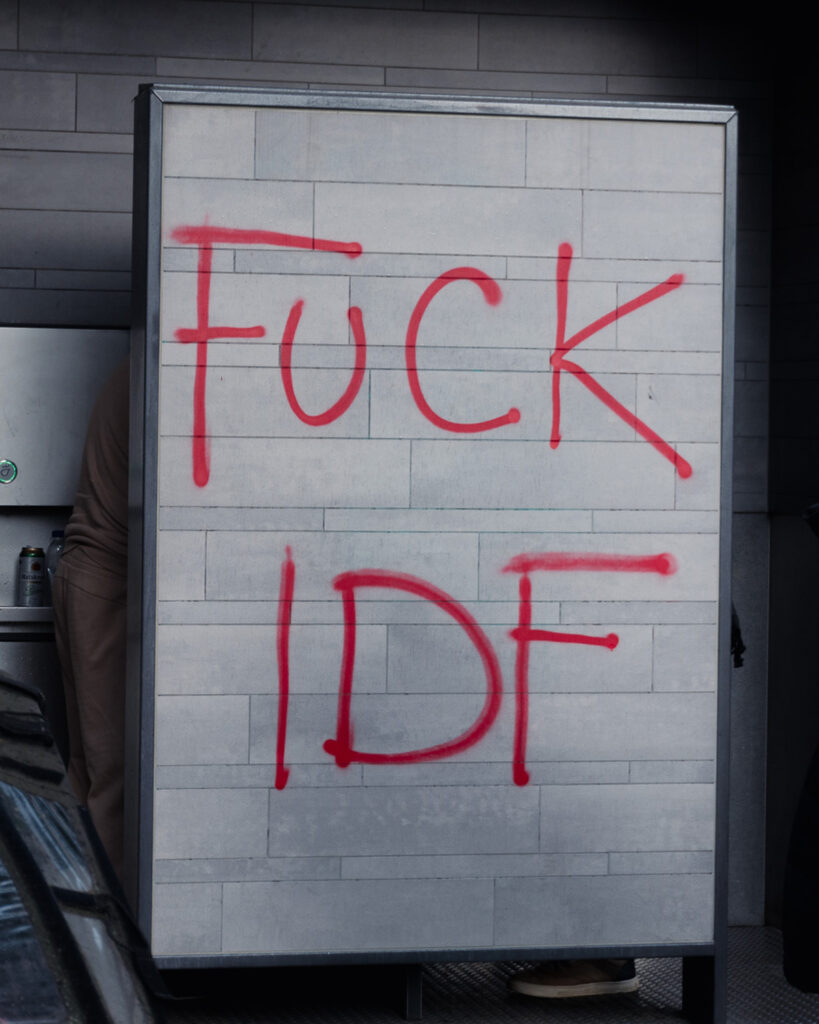

Fascism for Palestine

“Then they came for the trade unionists’’

… but what happens when the Trade Unions come for you?

On 22 February 2025, Verdi, one of Germany’s biggest unions, organized a protest called Unkürzbar, aimed at resisting cultural funding cuts. Paradoxically, Verdi banned using the word Widerstand (resist) in chants and speeches. The star speaker, one of the directors of a cultural center called Oyoun, was denied the platform to give their speech midway through the march despite Oyoun being one of the first cultural spaces to bear the brunt ideologically motivated funding cuts. The Palestine block, also protesting the crackdown on cultural spaces, was berated and isolated. Verdi organizers in red and yellow vests, acting as civilian enforcers, kettled protesters till the police stepped in to inflict their repressive measures.

Flakin’s article says, “Yet despite their bureaucratic leaderships, unions still form a foundation of working-class power, and a potential starting point for real struggles.”

Fascism aims to destroy unions by diminishing them as a starting point for real struggles. Hasn’t this already happened concerning Palestine? Isn’t the banning of the word ‘Widerstand’ a worrying sign for any union that would embrace a struggle? This is not the only instance in which Verdi has supported Staatsräson over basic rights. Likewise, many organizations in Germany do not dare to organize for Gaza without being punished by the state’s repressive apparatus.

There have been many definitions of fascism from Mussolini and Trotsky’s to Robert Paxton and Umberto Eco. Within these we see traits relating to the state’s behavior and deviation from democratic norms.

Fascism in today’s reality transcends these definitions. It has become the concerted effort to enforce an exclusive, nationalist state narrative with all of the state’s instruments working in unison, limiting rights and access to justice only to those who subscribe to this narrative, while forcefully subjugating the ability to mobilize for those offering a legitimate counter narrative and framing them as enemies.

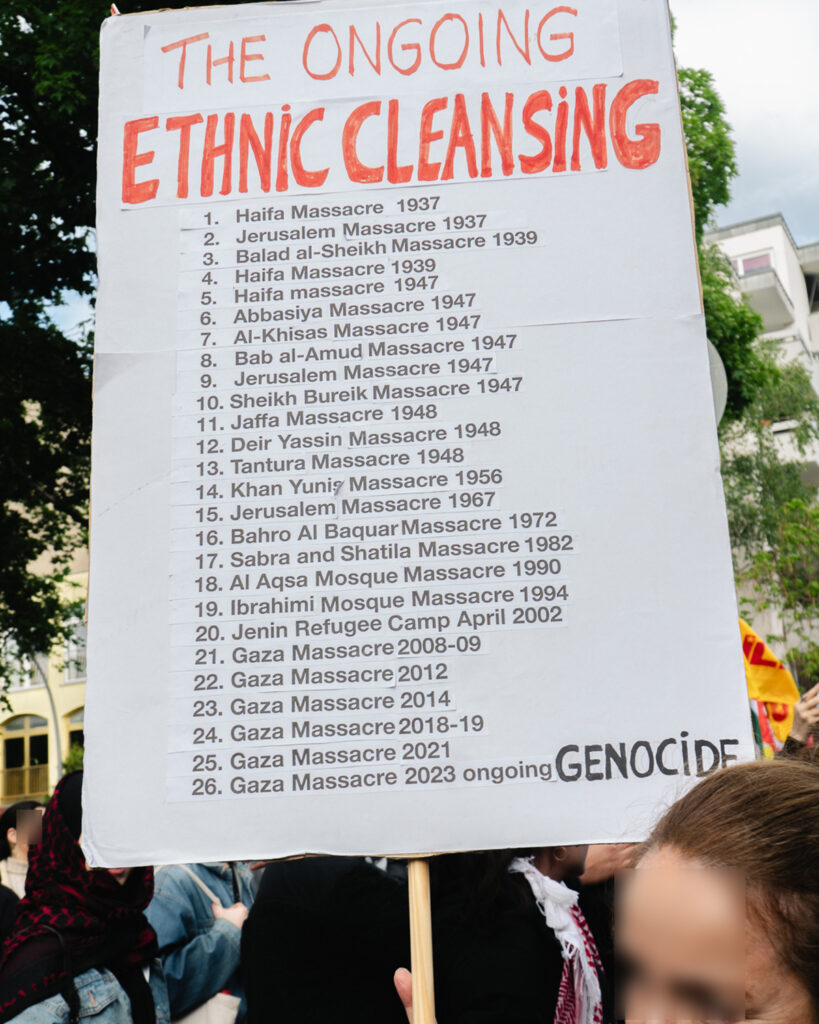

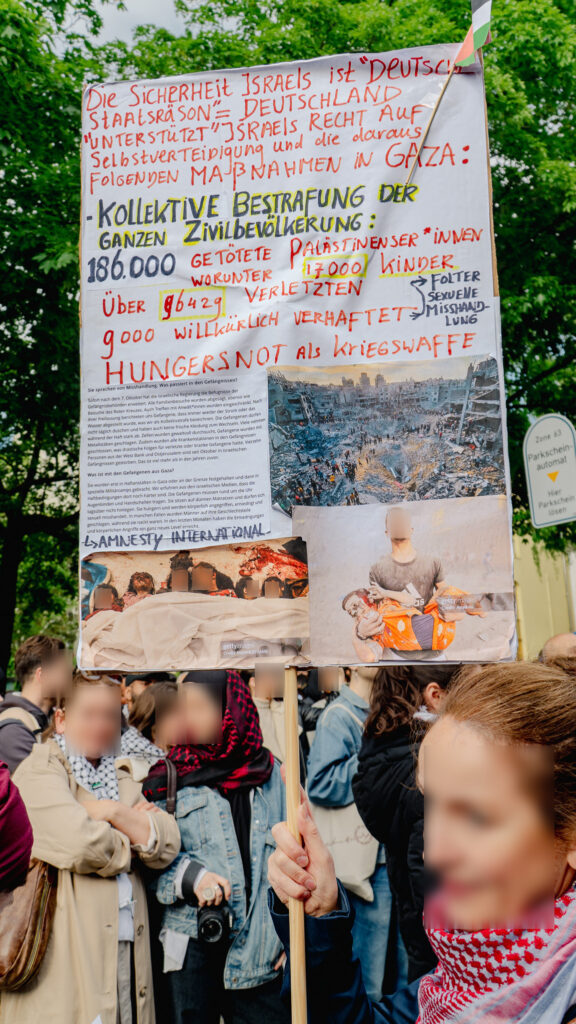

Germany’s interpretation of Staatsräson as unconditional solidarity with Israel is an outright expression of German nationalism as a proxy to Israeli ethno-nationalist fascism. It serves to undermine the rule of law and justify the suspension of civil liberties to protect the far Right Israeli government from criticism as they perpetrate a genocide.

Under the auspices of Staatsräson, people advocating for Palestine have experienced the vilification of individuals and groups with smear campaigns that dehumanize them as antisemitic terrorists; deportations of not just Palestinians but those who attempt to stand in solidarity with Palestinian rights; laws for exmatriculation to expel students out of universities; an archive of cancelling and silence to end the livelihood of individuals and organizations; a trade union against Palestinian civil liberties; targeted police violence; unified media propaganda denouncing protests, denouncing events, denouncing artwork without proof; police presence in universities exercising violence and excessive force; political interference in universities overriding university officials; police intimidation of venues that host high profile events on Palestine; crackdown on representing Palestinian voices in public spheres; a crackdown on cultural and academic institutions that would foster debate; lack of due process; house raids; restriction of right to protest; surveillance; device seizure; police carrying orders instead of implementing the law; banning of speaking certain languages; censorship of symbols and slogans; suspension of other civil liberties that include freedom of movement, the right to be free from bodily harm…

…this is not ‘normal’ capitalist repression, this is fascism.

On the foreign front, Germany is adamantly supporting weapons for a genocide in defiance of human rights, international law as well as EU and German law. The German government and their aligned media have offered justifications for breaching international law, bombing schools and hospitals, and the dehumanization of thousands of men, women and children, with implicit and explicit approval of bombing hospitals, killing paramedics, sniping children, forced displacement, starvation and targeting journalists.

But there are many parties and it’s not that violent, so how can it be fascism?

A fascist state traditionally does not allow for plurality of parties, but would we exclude calling a state fascists if the plethora of parties agree on fascist policies? In Germany all the ruling parties are genocide supporters, and the majority of parties that may object to the mass killings are at best genocide deniers. There is no electoral route to change the state’s suspension of civil liberties for Palestine supporters, nor to end the co-perpetration of genocide. There is no possible electoral pathway to end the dehumanization of Palestinians in Germany.

It may be argued that the levels of violence and repression are not as high as they have been historically when fascism emerges, but there are two issues to point out. First, fascism does not need to be very violent if there is not enough resistance, and indeed, there is not enough resistance within German society and institutions to warrant more violence as long as repression is successful. With a high trust in German institutions, their failures are accepted by society, and therefore, there is no need to repress society using violence. Out of European countries, the levels of mistrust of the police in Germany are the lowest. They do not need to exert their ideology with violence, nor justify it when it happens. Any lie they make up will suffice. Having been completely vilified in both state-owned and private media, social media can be seen flooded with the word ‘Deport’ in response to police violence videos against the Palestine solidarity movement.

Second, it’s simply not the intensity of violence as much as the quality of violence. German police are perhaps not as violent as French, Greek, or Italian police, but they are ideologically motivated, selective, and almost consistent in how they apply violence. Police violence alone does not constitute a fascist state, nor a police state for that matter, but the underlying reasons do. People use the term police state to describe Germany, and I don’t contend that. Not because I agree that violence is what makes a police state, but that the description is correct even if the reasoning is not. The practice of making up rules to inflict bodily harm, setting up laws to grant impunity to law enforcement personnel, surveilling and pressuring venues and institutions to cancel events and talks, threatening venues like Kühlhaus, Jungewelt and BUM with permanent closure, raids on activists and notices to forbid them from joining protests—all these are more in line with the police state than the quality of violence, and indeed more aligned with fascist tactics.

Weakened institutions and organizations

The other sign of fascism is the failure of institutions to fight an onslaught of racism. It’s not just Verdi, but many German institutions and organizations charged with fighting authoritarian tendencies that have failed Palestine in the simplest of tests. The Deutsche Presserat has failed to protect journalism and fight the dehumanization of Palestinians and Palestine supporters, the German chapters of Amnesty and Reporters Without Borders (Reporter Ohne Grenzen) have failed to live up to their international mandate. Reporter Ohne Grenzen have echoed the rhetoric and sentiments of the German state when it came to reporting about press freedoms, and Amnesty Deutschland stood by for months and months as protesters’ civil liberties were significantly infringed on systemically and systematically.

Even the courts are starting to fail civilians in terms of acquiring justice or even making sense. We are seeing politicized verdicts such as condemning ‘‘have we not learned anything from the holocaust?’’ as relativizing the holocaust while people chanting Nazi slogans are acquitted.

Is partial fascism not fascism?

Fascism is not a switch, and once it’s turned on, all forms of resistance become futile; it’s a process that is crowned by the success of a fascist regime. If it were true that fascism does not allow any resistance, then what is the point of anti-fascism if fascism doesn’t exist till it becomes totalitarian? We cannot refrain from calling the process of building a fascist state fascism simply because multiple parties exist, judiciary is not yet fully coopted and a cult figure has not yet appeared. Germany is a dormant fascist state that is currently being activated.

The mechanisms used to repress Palestine solidarity such as the resolution on Jewish life (Nie wieder ist jetzt—jüdisches Leben in Deutschland schützen), deportations and exmatriculation will be used to repress whatever opposition comes next, whether it’s climate activists (already bearing the brunt of this), or other minorities not aligned with conservative values.

One of the reasons that upset people I spoke to about Flakin’s piece is that it undermines their experience and resorts to definitions that have an outdated context. The people living through Germany’s policies are experiencing a suspension of their civil liberties and a breakdown of laws, organizations, and institutions in place to help alleviate injustices. To them, there is only one party in Germany: it’s the pro-Israel party. All the papers and media might as well be just one, demonizing and dehumanizing Palestinians and protesters. How can we tell people who have been subjected to immense racism, raided every other month, and deprived of their right to assembly, speech, and believe that this is not fascism?

But perhaps it only becomes fascism when it starts happening to you.

Maybe in hindsight, the success of this trajectory would be called something else by academics and historians, but does it really matter that people call it fascism as it presents all the same symptoms? Calling it fascism now helps us understand what we’re up against. The process of looking into what is not fascist to prove that it is not fascist is not a useful exercise.

Nevertheless, whether we call it fascism or not, there is a need to fight harder in order to prevent fascist success. Perhaps being in the middle of the poem, you may not want to call it fascism yet because of performative electoral politics. But in the process of visiting the experiences of those in the Palestine Solidarity movement one thing is certain: it’s more fascist than most think.