Q: Hello Taras. Thanks for talking to us. Could you start by telling is a little bit about yourself?

A: I’m originally from the Western part of Ukraine, from a city near to the Polish border. It’s a rather conservative, and religious region. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union it has moved in a nationalistic direction. I studied sociology in Kyiv and connected with activists in the student trade union, and engaged in direct action. This was around 2010-2011. From anarcho-syndicalism, I became a Marxist. And then Maidan came.

Q: There was a lot of confusion in the West about Maidan. Some people called it a left-wing uprising, some saw it as Fascist. How would you categorise it?

A: I would say that it was neither Leftist nor Rightist. It was a popular uprising increasingly dominated by the Svoboda party and other far right groups. We clearly saw that although the far right did not participate in a lot of protests, they were the most visible. Repression and street violence against the Leftists prevented their profile.

They managed to bring down the Lenin statue in Kyiv and other cities. After that it was about the Ukrainian language. They were quite successful – although Svoboda lost in the election. But they allowed discourse for pro-Maidan people, contributing to splitting Ukraine into anti-Maidan and Maidan.

They were able to do this because the core of the Maidan agenda was just an anti-authoritarian one. Of course it was also about integration into the Euro, but for the people on the streets, the first protest was more about anti-authoritarianism.

Their visible involvement, fueled Russian media propaganda which underlined the involvement of Nazis at the protests. As the liberal opposition in Ukraine did not distance themselves from the far Right, this furthered the split, which continued until the current war.

Q: So, three months ago, before Putin’s invasion, what was the political landscape of Ukraine?

A: Three months ago, Zelensky was quite a weak president. He won the presidency with an impressive majority – the first absolute majority in modern Ukraine, avoiding a coalition government for the first time. But then a lot of people were disappointed that he didn’t manage to deliver on his promises, especially on his promise of peace.

There were hints of a comeback of former president Poroshenk. In the second round of the previous elections, Zelensky had crushed Poroshenko. There was a hint that Zelensky was losing support. People were also getting disappointed and moving out of politics.

There was also some repression against the so-called “pro-Russian opposition”, which was stronger in the traditionally Russian speaking part of Ukrainian society. One of the opposition leaders, Victor Medvedchuk, who named Putin as godfather to his daughter, was put under house arrest. The pro-Russian opposition had a little support but was quite oppressed and lost support after the annexation of Crimea and the Donbass conflict. People who might have voted for them just moved out of Ukraine.

Ukraine politics was at a dead end. Previously there had an equilibrium between the pro-Russian and pro-European camps. This was no longer the case.

Q: Was there any sort of internationalist left wing opposition outside these camps?

No. First of all, the so-called pro-Russian faction is more left wing in economical questions. They are against strong pro-market reforms. They are not really leftists, but they’re a bit social democratic. In contrast, the pro-European camp is rather neo-liberal.

Polls from three or four years ago show that Ukrainians don’t want to be described as Leftists, to be seen like a Soviet. At the same time, they support some of the central demands of the Left such as the nationalisation of key sectors or a progressive tax system. It is quite paradoxical .It is even more complicated as the Svoboda party is far right, but their economic programme also calls for the nationalisation of key industries.

However, in cultural terms, both the pro-European and pro-Russian camps are conservative. Maybe a bit less among the pro-Europeans, but a lot of them are still homophobic, and so on.

The internationalist Left groups are quite marginal, mainly centred around Kyiv. Most people move to Kyiv for education.. There is a Leftist community of about 1000 people.

In 2010 the Left was more or less united. But then, especially during Maidan, they split into different sections. This was still so three months ago.

I was part of a social movement, to found a workers’ party in connection with an independent trades union. But it was unsuccessful and then tried to help individuals with labour relations. Their main demand was to freeze the conflict.

Another group, more intellectual based (known as The Reds) embraced the Soviet identity more and tried to speak to the original pro-Russian, Russian-speaking camp. They argued that the conflict should not be frozen but resolved and that Ukraine needed to embrace the Minsk agreement and reintegrate Donbass. This argument about freezing the conflict or reintegrating Donbass was a line which split the Left.

Q; So, if I understand it correctly, towards the end of last year we have a pro-European ruling party which is losing support, a pro-Russian opposition, and a tiny Left which is mainly based in Kyiv. And then Putin invaded. How did this change Ukrainian politics?

A: It wasn’t so much pro-Russian politics that were gaining support but the pro-nationalistic politics of Poroshenko. The pro-Russia position was stagnating, due to repression and loss of electorate. They were also splintered and couldn’t agree on how to build a united front against the other camp.

Regarding the invasion, one could say that Putin miscalculated. He probably thought that it was a perfect time to invade due to the political dead end in Ukraine. The brutal force of the invasion shocked me. The vast majority of people in Ukraine was shocked.

Zelensky acted as the president of a country should. He is a bit of a showman but this served him quite well in these times. Every day he makes a video message promoting morale across the country and the vast majority of people have united under his banner against the Russian invasion.

Some of the Left joined the militia in Kyiv where they got rifles and they’re ready to defend Kyiv against the Russian troops. Another Leftist faction opposes the invasion but has remained quite silent. At the beginning they also tried to criticize Ukrainian actions but then – maybe due to some threats, I don’t know – they just stopped and now remain silent.

The same for the so-called “pro-Russian” opposition – who mainly remained silent. There was a demand by Putin that one of the “pro-Russians” Yuriy Boyko should become prime minister, but Boyko very quickly said he wasn’t interested, saying he doesn’t have anything in common with Putin. The mayor of Odessa, Trukhanov, also has a pro-Russian reputation but is now saying that they are defending Odessa to prepare against a Russian invasion. I can’t think of any politician who would publicly saying anything in support of Putin.

This has consequences for local Leftists. Although they didn’t support Putin and some supported Ukrainian self-defence efforts, it’s still dangerous for some of them to remain in the country.

Someone I know, Alexander, was active in anti-Maidan but was targeted by police and some local militia who were originally part of the local Nazi scene. Attacked in his own house, he was tortured, his head was shaved, as was that of his wife. They were beaten up then he was taken to jail. They are accusing him of treason. It’s horrible.

It’s also very difficult to organise his defence. It’s hard to find a lawyer who is able and willing to defend him. If you say now that there are also some Nazis in the militias, you will be accused of helping Putin and his talk of “denazification”.

Q: We’re now getting news reports that German Nazis are now going over to fight. Do you have any information?

A: I don’t have any specific information but I also heard this, it’s quite logical. They have had connections with the Azov battalion. The movement around Bilesky, the leader of Azov is connected with Der Dritte Weg and other organisations, so he’s a real Nazi. But one should say that of course Russia has their own Nazis, and in Donetsk and Luhansk they are also using Nazi brigades in their battalions.

I think that it will be very important to criticize this Nazi involvement after the war ends. Especially if Ukraine is going to be accepted as a member candidate to the EU. What we as Leftists in Germany and the EU can do is put public pressure on our national governments that the Ukraine government examines these cases of torture; to fire Nazis from all official positions that they currently hold in the army; and to withdraw all government funding that they enjoy now.

All this should be done, but of course for people like Alexander who are now facing prosecution, it could be too late. Maybe they will torture him further, or maybe even kill him using the war as a pretext. This is a real danger.

Q: Let’s move onto Germany, because we’re in Germany. What should the German government do and what shouldn’t it do? What are your demands?

A: We don’t have any demands for governments. But I think that all people in our diaspora of Ukrainian Leftists in Berlin would all support sanctions – preferably an oil and gas embargo rather sooner than later- to hit the Putin régime hard. As it’s getting warmer, maybe Germany won’t be dependent on Russian gas imports.

About weapon exports I would agree with Gregor Gysi responding to Sahra Wagenknecht and other former Putinversteher [ “Putin understanders”] in die LINKE. Now, they are of course opposing Putin’s invasion but they think that we need to blame both sides. I support Gysi because it’s important that the German and international Left should acknowledge and honour the right of Ukrainian people to self-defence. For Ukrainian people to carry out this right, they need some support.

I don’t like the patriarchal belief that adult men can’t leave the country because they all need to fight, while the women should leave with the children. I also don’t like it that some war criminals would be freed from jail to fight. But in general I think that there is an enthusiasm of people to fight and defend their livelihood and their cities against invasion.

After Maidan, no part of the country wants to be part of Russia – see the videos from Kherson and other Southern cities currently under Russian occupation. All across Ukraine people are willing to defend their country and they should get support.

Q: What sort of support?

A: Now, lethal weapons should also be considered. The main thing to do is just stop the aggression and stop the invasion. But the support should be balanced. It’s not only about lethal weapons. It’s about medicine, it’s about humanitarian help. All options should be on the table.

I’m also thankful if people are willing to help civilians, make donations to charities in Ukraine, helping old people and children who are especially affected by this war. All these are important. All little steps help.

Q: In terms of stopping the war, do you have any contact with the anti-war movement in Russia?

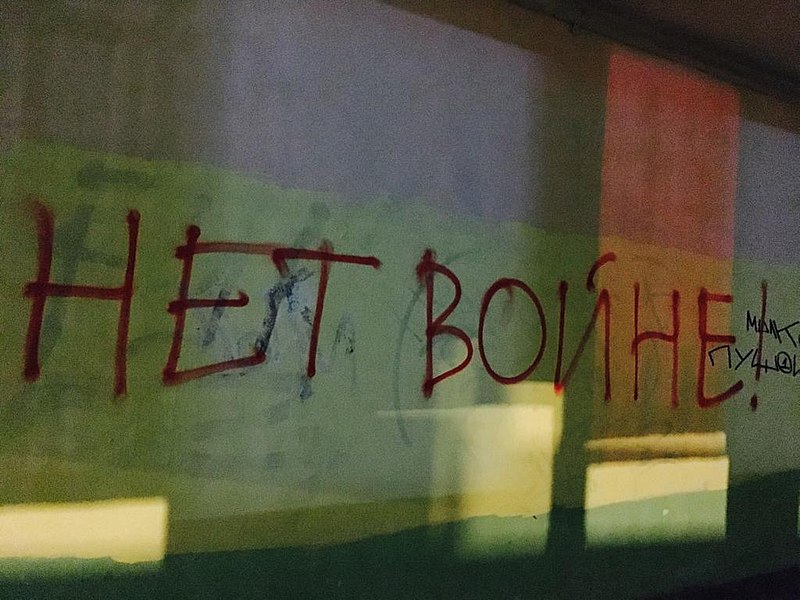

A: Yes we do. A comrade of ours, Sasha, is on the border of these two groups. She’s originally from Ukraine, but grew up in Russia. Five or six months ago, she moved to Berlin, but she’s also an active member of a socialist movement in Russia, especially in St. Petersburg and Moscow. Sasha helps us with our initiative Host Ukrainians and is also organising protests. She has a very important function, as these harsh new laws in Russia, have heavily criminalised all opportunities to criticize or organise protests. From outside Russia, she’s free to post in social media. They also have a call centre to help people who are currently under arrest because of the protests.

This is a very important job, but it’s a thankless one. I really appreciate their effort. It is the only way to remain moral, as a human, to protest this absurdity. But there is such a level of oppression making a lot of people in Russia just afraid.

Now it looks like they are damned to be crushed by the régime. This all could change due to sanctions. Russian society could get fatigued. This is a difficult trade-off for activists: to oppose this absurd war but to remain intact. Maybe you need to go underground and become a partisan guerilla group. They still try to remain legal but it has become more challenging each day.

We really appreciate what Sasha is doing, but as Ukrainian Leftists we don’t know how we could help. We honour their attempts but we don’t know what we can do.

Q: You mentioned Host Ukrainians. Can you say something about the work you’re doing in Berlin for Ukrainian refugees and how people can help you?

A: As activists, we come from different regions of Ukraine. Most of us moved to Berlin to study. We organised events, some public some private, to discuss Ukraine.

Host Ukrainians’ was the most serious initiative. On the first day of the war, we made a call to meet together. We were all shocked and met in my flat. This idea emerged to make a forum for people in Germany who could offer some space.

We reached out to our German contacts. I have been in Germany for 7 years. We all have political contacts. We didn’t expect it to be a huge success, but the next day, we had 100 answers. Now we have something like 1,000, and a quite impressive database of people willing to share their flat with Ukrainians. Especially in Berlin, but we also have people in other cities like Leipzig and Dresden. We are also looking for new people, so if somebody can offer accommodation, we are interested.

We want to accommodate Ukrainians temporarily. To be a bridge when there’s already a lot of refugees, but official institutions haven’t yet managed to accommodate them. So, our database has Ukrainians looking for a place and one with Germans offering somewhere.

Sometimes it takes a few days, sometimes a few hours. We may need to accompany people who are outside Ukraine for the first time not knowing German or English. Some people have special needs like medicinal support, children, etc. The first couple of weeks will be the most difficult time and we try to make our small contribution to help to accommodate people.

There are a lot of other initiatives, but ours is special because we have a special relationship with the German Left. It’s not a big secret that the mainstream Ukrainian diaspora are mostly anti-Communistic. This makes it hard for them to address German Leftists who already in 2015/2016 managed to establish quite impressive networks to help Syrian refugees.

Q: Do people need to be able to speak a certain language to help?

A: We don’t care what language they speak – English, German or whatever language you have. But we are looking for volunteers who speak Russian and English in order to translate. In Ukraine, only five, ten, maybe fifteen per cent know English. German even less.

Evangelical and Lutheran churches are accommodating people, and today I got three requests to translate. In seven years it is the first time my Ukrainian skill is in demand. (laughs)

It’s a really busy time and we are all volunteers. We don’t have the plan to formalise it, but we have free time and want to help. It is important to be active for two-three weeks accommodating people, and we hope that then Berlin and Laender will react to build the necessary capacities.

Q:If somebody wants to help either host people or translate, how do they best get in touch with you?

A: Volunteers to translate can send an e-mail to host.ukrainians@gmail.com. If you know Ukrainian or German it is even better, but if you can translate Russian-English that’s ok. If you can accommodate people, you can fill out this form. This provides the structure to help us process the offers.