Haustürgespräch translates as ‘doorstep conversation’. For most people this phrase probably evokes awkward experiences with earnest strangers hawking dishcloths or religious conversion. Most often these are unwanted encounters, kept as brief as politely possible. We not only wish not to be disturbed but also feel slightly uneasy at being collared right where we live. Our thresholds form the boundary between what we wish to deem our private sphere and the world outside. Even in a world of boundless social media where people happily post up pictures of their food, family, significant life-events and have daily meetings on Zoom; our actual physical living space still feels much more sancrosanct, a highly personal domain.

But what if the real threat to this sense of home and safety is not from a random salesperson or spiritual evangelist? What if it’s from the very organisation to which you pay money to live there? Or from a system which allows your home to be an object of financial speculation, that could easily price your tenancy out of your reach by the handing over of distant contracts you will never see? What if your neighbourhood is changing out of all recognition as wealthy owners turf out longstanding independent shops and fellow neighbours and you fear you’re next?

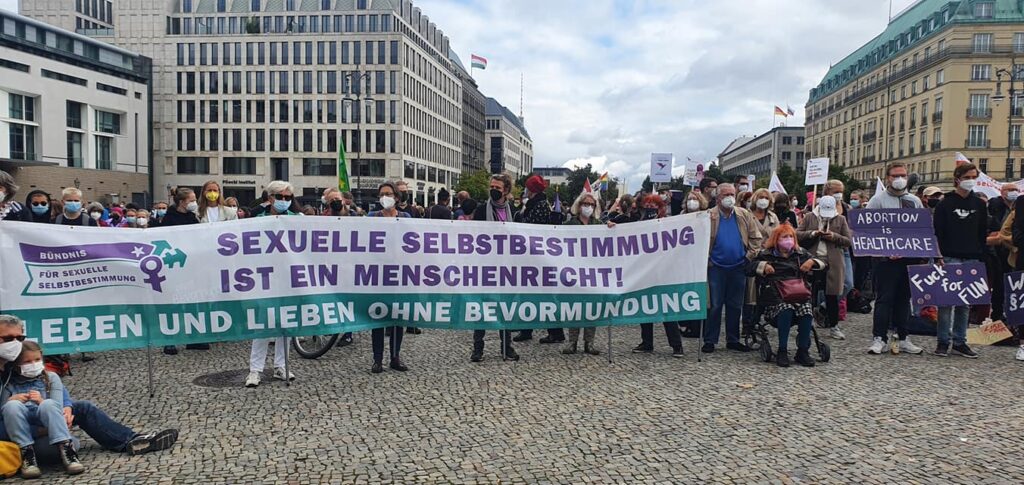

This is the terrain from which the initiave Deutsche Wohnen & Co Enteignen has arisen. Having passed the first two hurdles of gathering enough signatures agreeing to the basic question: Should the Berlin Senate take (back) into public ownership the properties of private companies like Deutschen Wohnen and Vonovia each of whom own 3,000 or more dwellings in the city? (the second petition garnered the most signatures ever in a Berlin referendum campaign) The initiative and all its signatories has earned the right to a democratic vote of all Berlin citizens on the same day, Sunday 26th September 2021, as the national elections.

The efforts of the campaign to ensure that enough citizens (I’ll come back to that word later) vote yes, or rather Ja, to these basic question, have ramped-up even more impressively than those seen during the second signature collection. Dozens of volunteers have hoisted placards onto lamposts, put posters up in shops, bars and bistros, newspapers have been given out to commuters at under- and overground stations at the crack of dawn, beermats and flyers (in six or seven languages) distributed in venues in the twilight hours and from weekend stands in parks, hundreds of leaflets put in post-boxes. And, yes, doorstep conversations have been taking place not only in the inner city but throughout its far-flung suburbs.

Having only contributed minimally during the signature gathering stage (mainly down to Corona caution), passing petition sheets round my closest neighbours and donating a sanistising kit to a local organising hub, I joined the Neukölln Telegram group late in August to find out how I might do more in this crucial run-up to the vote. Someone posted up a call to join a team ringing doorbells in Rudow, the southern-most part of Neukölln, so I made myself known to the contact person and headed to the meeting point outside the U-Bahnhof on a Friday early evening.

Toting one of the distinctive yellow and purple bags, (bought at MyFest in 2019) I was easy to spot and the organiser beckoned me over to where she was standing with a group of other game but rather nervous looking comrades. Once everyone had arrived, we were asked if any of us had done this before, most hadn’t. Someone who had gave a helpful workshop: Giving our first names and that of DWE by way of introduction was key, then asking if the person had heard of the initiative and if so, what did they already know? Letting them speak, rather than doing some hard-sell bullet points of why to vote Ja, getting a human connection, not just spouting information. We are, after all, all renters, all in similar predicaments. Relay a personal story yourself if it’s relevant.

This was a relief, the other thing I’d been nervous about, along with my imperfect German, was my incapacity to reel off a thousand facts and figures. Don’t get into an argument, we were advised, if the person is hostile, thank them for their time and move on. Above all, don’t take it personally if someone is unfriendly and if they’re downright nasty, contact the organiser and get some emotional support.

There was a particularity to this door-knocking round, in fact the whole weekend had been named after it: Wochenende der Genossenschaften. This had something of a double meaning I was later to reflect. A Genossenschaft in German housing terms is essentially a cooperative but in Germany these are rather large concerns. In recent weeks, a certain Genossenschaft had sent out a letter to its thousands of members falsely claiming that the DWE campaign, if successful, would expropriate cooperatives, because they too sometimes had over 3,000 dwellings. No-one is sure why this disinformation campaign was launched but on this Friday evening, we were equipped with our own letters in sealed envelopes setting out the actuality, that cooperatives would in fact be exempt from any expropriation because their financial model does not prioritise profit for external shareholders and that instead, they guarantee fair rents and decent conditions for their member-residents, and were as such role-models. So, at the very least, if someone blanked us on the doorstep, they could be given or posted the letter containing this reassuring reality.

The time had come to get into pairs. The doorstep conversations aren’t advisable as a solo activity, for a start it’s exhausting so it helps to have someone to both take turns with and to reflect on technique and efficacy. A tallish young guy offered to pair up with me, saying we had a good demographic range. It’s not often that being older is an advantage but as many of the Genossenschaft members would be over 50, I knew we’d make a good team. He, let’s call him Tom, had done it before and he did the first five or six conversations, encouraging me after to start the next few.

The interiors of the buildings were, in this instance, clean and well-looked after. Some people weren’t at home or didn’t answer the door. Those who did were mostly courteous and curious. Our diffident introductions worked well to assure people we weren’t only trustworthy, we were absolutely on the same side. Everyone wants a secure place to live, an affordable rent, wants community. Some had read the letter from their Genossenchaft but most wanted to give us the benefit of the doubt.

Once I did my first few, I gained in confidence. No-one looked down their noses at my mixed up cases or adjectival endings, they were just curious as to what I wanted to say. And allowing them to talk first made it easier, finding out where they were at with things. The buildings in Rudow were lower rise than usual, only three floors, but nevertheless after an hour and a half of flights of stairs and the uncertain stress of waiting for someone to open the door, I was pretty wiped out. I travelled back with four of the crew and though the offer was there to go to a collective DWE get-together, I was conversationed out.

My next stint was in Britz on the Sunday afternoon, more Genossenschaften. I recognised B, another comrade from the Friday team. He looked upbeat but told me that the day before had been tougher, more hostility and rudeness. He had, he said, boned up on some useful info to counter some assumptions he’d encountered the previous day. We all did another workshop and were invited to contribute our own reflections on what seemed to work or not. I teamed up with B, the comrade I’d spoken to earlier.

The buildings were doubly high so we made use of the lift. We made contact with around 50% of the residents. This time, there was an interesting dynamic in that we started off with the softer introduction but if there any mistaken assertions or questions, B was ready with a clear set of facts and figures that were accessible and convincing. I was moved and impressed that he had responded to the hostility of the previous day with an impetus to be on top of a concise set of information. The residents took this on board and thanked us for our efforts.

Occasionally, on both days, there were people who weren’t even aware of the fact there was a referendum vote. They’d either assumed that the signature collection was the end goal or the whole campaign had simply passed them by. It’s easy to assume from one’s bubble of inner city political engagement, that the whole of Berlin are up to speed on what’s going on. This stressed even more the importance of personal contact, of conversations, of going outside one’s comfort zone.

The most recent time I took part was in an area of Neukölln near the station of Köllnische Weide. We met in a park, where there was to be an info stand full of DWE campaign literature in almost every language possible. One particular flyer was aimed at those without voting rights. We were told that the Siedlung (housing estate) that we were about to visit would have a higher percentage of people without the right to vote, non-citizens in other words, who nonetheless pay rent and other contributions and are as affected as anyone by the laws and conditions of the country. The flyer was to invite them to join a group to discuss with others like themselves the need to have rights within the civil society.

Our group was twice as big as the previous weekend but as someone who had had more experience, I was asked to relay my thoughts. In a serendipitous role-reversal, a young guy teamed up with me looking unsure and nervous. The buidings were more like tower blocks. We were told they had, up until the early 2000s, been public housing but had, in a shameful move by the leftwing Senate at the time, been sold to the private sector. They were now in the hands of Deutsche Wohnen.

The contrast with the Genossenschaft communal interiors was stark. Only one lift was working in the 12 storey tower we went in. The working lift had a gaping hole at the back, exposing it to the casing of the shaft. A resident came out and assured it was working. The conditions were an eye-opener if one had assumed that this company is all about high class renovation. We took the lift to the top and worked our way gradually down. It was gradual because we spoke to 80% of the residents. Half hadn’t heard of the campaign, about a third welcomed flyers in their first language, often Arabic or Turkish reading them avidly, about a third did not have voting rights. One woman, Croatian, was living with six others in a two bedroomed flat and had been applying in vain for re-housing over the last several years. We gave those concerned the non-citizen flyer, apologising to the woman there was none in Serbo-Croat.

The hallways were dingy and a number of doors were damaged but the people were uniformly friendly and grateful for the information and those who could vote, positive they would in the affirmative. A door behind which we heard several yappy dogs, was opened by a smiling woman who said she was voting Ja before we said a word. My companion’s confidence grew at each descending floor. The experience was sobering, moving and politically galvanising.

Yes, there were techniques, yes, as my last companion put it, there was a kind of flirting at play and yes there was the hope that all we spoke to will vote Ja on 26th. But most of all a dialogue was being started about fairness, ownership and the right to a home without fear. People who would normally never meet were realising how shared their wishes really were.

Carol McGuigan has lived in Berlin for 10 years, gaining dual citizenship in 2018.