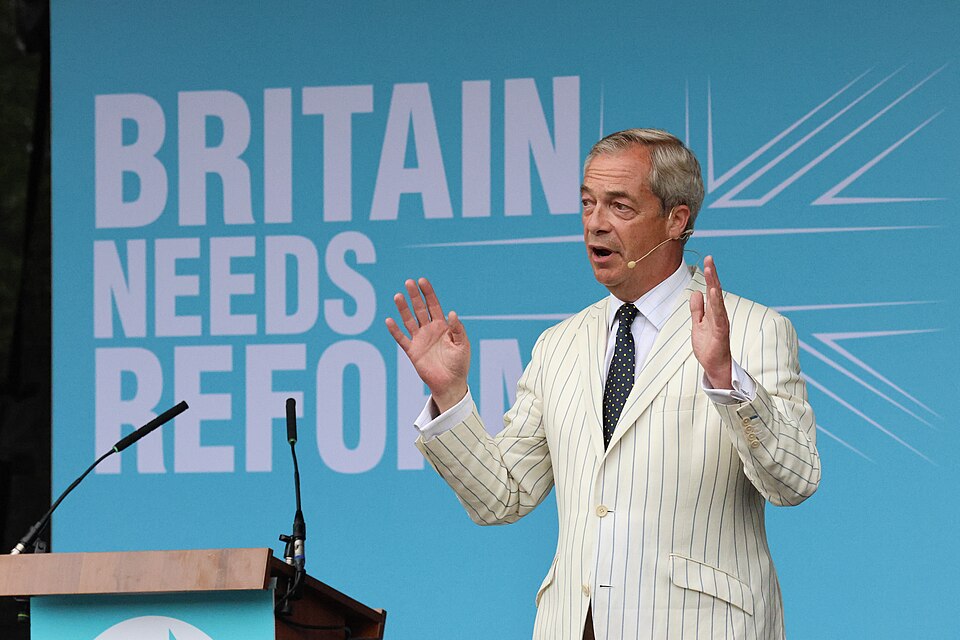

Nigel Farage just had the weekend he’s spent his life rehearsing for. Not in the shadows, not on the margins, not even in the smoking area of a middle England pub, five pints deep, fawning over Trump. But centre stage, in a political reckoning too many pretended would never quite arrive.

Reform UK, the far-right party led by Farage, is no longer a flag-waving nuisance on the sidelines of British politics. After slipping into Parliament last year, it has now won two mayoralties and seized control of ten councils across the UK, including, with a particular twist of symbolism, Durham, a place deeply embedded in the mythology of Labour’s past.

Durham was the first county council ever run by Labour, and the birthplace of the miners’ gala, a historic celebration of workers’ solidarity. Labour lost control there in 2021, but it wasn’t the Conservatives who tightened their grip this week. It was Reform—Farage’s xenophobic, division-spreading, spite engine—seizing the cradle of working-class political consciousness. He has since declared his party the “main opposition,” and disturbingly, the claim carries a certain coherence. Reform is not yet a party of government, but it has become the party of resentment, of rupture, of consequence.

But what does Reform stand for? Beneath the talk of DOGE-esque efficiency, free speech, and a “war on woke” (ooops), lies something more familiar: the steady churn of blame. Migrants. Outsiders. Anyone deemed not quite British or “normal” enough. It is a party fluent in both the language and the logic of nationalism. And in places where people feel that everything has already been taken, that language begins to sound like a plan.

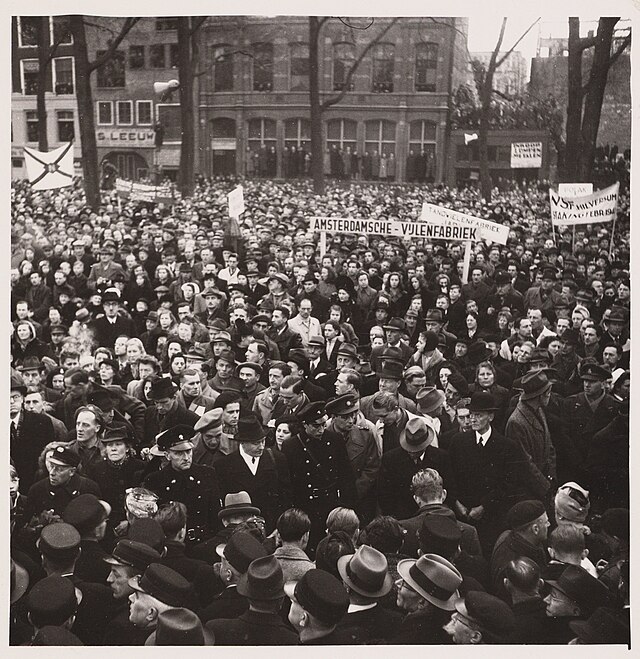

It is tempting to cast this as a shock, to speak of a sudden lurch, a rogue current, but there’s nothing sudden about it. The conditions were laid carefully over decades: industries shuttered, communities dismantled, services stripped to the bone. The promise of something better replaced by the reality of nothing at all, and then anger. Reform didn’t invent that anger. They simply arrived at the right time, to cash in on an outstanding political debt accrued slowly, painfully, and without apology since the 1980s.

You can see the consequences not only in the councils that flipped, but in the towns and cities that came dangerously close. Places where loyalty has worn thin, and trust has quietly left the room. Doncaster, where I grew up, came within 700 votes of tipping over. A result close enough to shake those still in power into breaking ranks.

A clear rebuke to Keir Starmer—delivered not in private but in her own re-election speech—the sitting Labour mayor of Doncaster, Ros Jones, criticised Labour’s recent scrapping of winter fuel payments for pensioners, the rise in employers’ national insurance contributions, and the tightening of disability support. She knows that in Doncaster, these aren’t abstract policy tweaks. They land sharply, and shape how people live, or whether they can live at all.

Like Durham, and countless other towns and cities now leaning towards Reform, Doncaster’s story is one of abandonment. These places once thrived on industry—coal, steel, railways—not simply as sources of income, but as cornerstones of identity. Work shaped community, and community shaped purpose. Then neoliberalism arrived, dressed in the language of modernisation and inevitability. In the 80’s, the mines were closed, public assets sold, unions dismantled. Investment, talent, and belief drained away. And what replaced it?

From my experience of growing up in Doncaster in the 90’s, it was replaced by a slow, visible unravelling: boarded-up high streets, rising violence, widespread addiction, prostitution, and a pervasive malaise that crept in like mould. You could feel it in the quiet of a once-bustling market, in the dusty stillness of empty shop fronts and in the way ambition was slowly sucked out.There was no single collapse or headline moment. Just the cumulative effect of being overlooked, year after year. Decade after decade. Politics rarely arrived except to promise, and those promises rarely came with delivery dates. Eventually, though, what did arrive was a sense that no one was coming. And in that absence, people looked elsewhere or gave up on politics altogether.

For some, turning to Reform is less about belief than about absence. It’s a response to the growing sense that Labour and the Conservatives no longer speak to them, or for them.

And this isn’t just about jobs and services. It’s about dignity. It’s about who is spoken for, and who is sacrificed. Labour’s ambivalence on Palestine, its retreat on trans rights, these too are part of the silence and part of why some chose to stay home. What we’re witnessing now isn’t chaos. It’s the cost of looking away.