It has been 17 years since Die Linke was formed at the height of the anti-capitalist movement. In 2009, the party won 12% of the vote (and 76 MPs), becoming the envy of the international Left. Just seven years ago, the party still had 69 MPs.

In the last general election, Die Linke failed to reach the “5% hurdle” traditionally needed to enter parliament, and got in only on a technicality. More recently, when 10 MPs left the party to join the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance), Die Linke lost its status as a parliamentary fraction and much of the money associated with it.

More importantly, the party, which was once a motor of social movements, has become largely invisible on the ground. In the face of significant demonstrations in support of Palestine, it has remained mostly silent. Recently, left-winger Christine Buchholz refused to take on the post of MP, saying it would put her into a permanent conflict with the party line on Palestine, war and other topics.

How could a party which still has tens of thousands of members experience such crises so quickly? Phil Butland, joint speaker of the LINKE Berlin Internationals group, looks at the rise and fall of Die Linke.

The last 25 Years of the European Left

The Left in Europe experienced three phases in the last 25 years, each lasting for roughly a decade. The first was from 1999 to 2007, starting with the WTO protests in Seattle until the G8 summit in Heiligendamm in Eastern Germany. This was a time of international mass demonstrations and social forums where the Western Left came together to discuss strategies and plan joint actions.

The most important two actions of this period both started in Italy. In July 2001, the G8 summit took place in Genoa. On the day before the planned large demonstration, cops murdered 23-year old activist Carlo Guiliani. The movement quickly mobilised and 300,000 demonstrated on the following day in Italy.

One year later, in December 2002, the first European Social Forum (ESF) took place in Florence. At the forum, a couple hundred activists attended an unofficial meeting to discuss the threat of the upcoming Iraq war. It was there that we decided to coordinate protests for the 15th of February. On that day, 15 million demonstrated against the war, and 40 million in February and March.

Growth of Left-wing Reformist Parties

Despite the large-scale demonstrations, war ensued and hundreds of thousands of Iraqis were killed. Social forums became smaller and less political, and the 2008 world economic crisis led to austerity politics, carried out both by conservative and social democratic governments.

For many Leftists, this showed that demonstrations and forums were not enough. For most people, “politics” is what happens in parliament. This meant that socialists must also fight in this arena. But what did “fighting in the parliamentary area” actually mean? For the majority, it meant voting in better left-wing MPs who could make better politics on our behalf. As new mass parties were formed, there was little talk about the role of the State, or how realistic this strategy actually was.

A minority did not believe in short cuts, nor that there could be a parliamentary way to socialism. Nonetheless, we had just spent the best part of a decade building social movements, and did not want to abandon the people who had been building them with us. Many of us joined the large Left parties all the while arguing that such parties meant little without strong social movements.

Those heady days are now well and truly over. The different, but in some ways quite similar, experiences of SYRIZA, Podemos, Jeremy Corbyn and Bernie Sanders, showed that it was not so easy for the Left to take over the State and use it for our ends. If you want to know more about the specific experiences in each country, I highly recommend Joseph Choonara’s article Revolutionaries and Elections.

Let’s take one early example. The Italian party Rifondazione Communista was central to both the Florence forum and the protests in Genoa. On the evening following Carlo Guiliani’s murder, Rifondazione leader Faustino Bertinotti appeared on Italian television saying: “whatever you had planned to do tomorrow, now everyone must come to Genoa.”

Three years later, Rifondazione was part of a governing coalition which voted for war credits. Now, Fascists are in power in Italy and the parliamentary Left is irrelevant. The Left in other countries has experienced similar disappointments.

The German experience

In Germany, Die Linke was initially able to combine Left reformism with anti-capitalism. The party emerged from the mass movement against the Hartz IV attacks on the unemployed. Many activists moved straight from the anti-globalisation organisation (ATTAC) to Die Linke. One of the party’s first actions was to mobilise for the G8 protests in Heiligendamm.

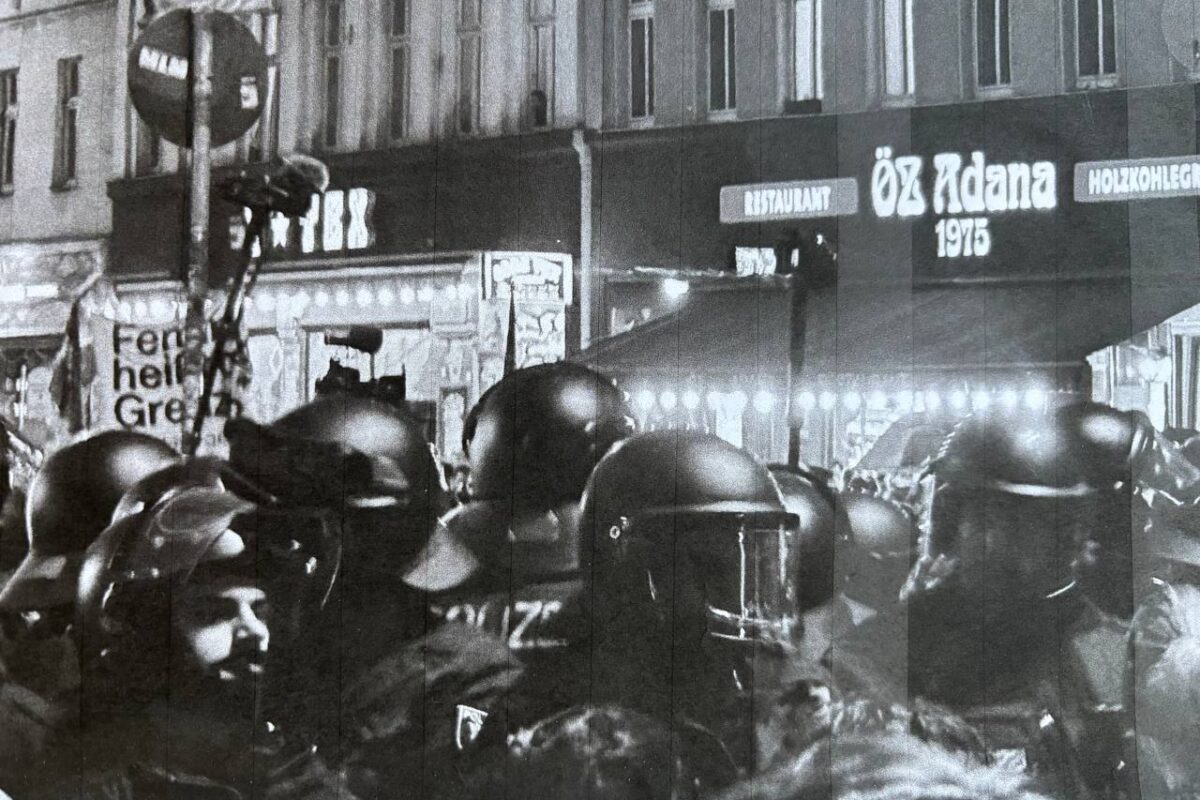

Shortly after that came the mobilisations by Dresden Nazifrei, which successfully blockaded and prevented the largest Nazi march in Europe. Die Linke was central to this mobilisation. It was both a reformist party and a motor of the movement.

The most important mobilisations of today are against the Israeli genocide in Gaza. Despite the occasional decent statement, Die Linke stands largely on the wrong side of the barricades. The nadir occurred in October 2023 when Die Linke joined the other electoral parties in calling a rally in solidarity with Israel.

Palestine is not an exception. The party played no relevant role in Black Lives Matter or in the movements against war and the climate catastrophe. Individual regional groups did support some actions, but a generation of activists has grown up believing that no parliamentary party supports them.

While all this has been happening, the Left of the party has been apparently on the ascendant. In June 2022, the left-wing Bewegungslinke (“movement left”), won a majority of posts on the party Executive. Despite this increased representation, the party’s practise has stayed the same. Winning leadership positions is no substitute for being an active part of social movements.

The limitations of Reformism

As social movements have receded, Die Linke has increasingly concentrated on winning elections. This was not always the case. In 2008, Die Linke in Hessen had the chance to join a governing coalition with the SPD and the Greens. They opted instead for toleration – allowing the SPD and Greens to form a government (no-one wants a CDU government), while not joining it themselves.

Deputy leader of the Linke parliamentary faction in Hessen, and key supporter of toleration, was current party leader Janine Wissler, a prominent member of the Bewegungslinke. She has since taken a much more pragmatic position. At a rally before the last general election, she argued that NATO would not prevent a coalition government with the Greens and SPD. In other words, Die Linke’s traditional opposition to Western imperial power could be negotiated away in exchange for a place in government.

This strategy did not even work in electoral terms. As Die Linke casually dropped most criticism of their potential coalition partners, voters saw no reason for voting Left when they could get exactly the same policies from larger centre left parties.

Areas of resistance

This does not mean that the Linke is a reactionary homogenous blob. The Berlin Linke Internationals, an organisation for non-German activists of which I am co-speaker, has consistently been anti-imperialist and pro-Palestine.

Originally formed to mobilise for the 2014 EU elections, the group has played a leading role in the fight against German/EU austerity in Greece, challenging the international far right, and defending abortion rights. The Linke Internationals organise an annual Summer Camp, usually attended by around 60 people. Party funding means that participation is free.

Yet relations with the Party are getting strained. Last year, following some problematic statements by Party leaders on Palestine, we decided to stay in the Party and fight for our positions, while monitoring the political situation.

Our work has been increasingly detached from party activity. Our successful weekly Palestine Reading Groups have been effectively run in the name of theleftberlin – the website which we run together with other left-wing activists. The website has an independent editorial board and is not connected with the party.

“Left” Alternatives to Die Linke

The formation of the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknacht has excited some people who were disillusioned with the direction in which the party was going. Wagenknecht has made much clearer statements against German militarism and in support of Palestine than most in her former party.

At the same time, Wagenknecht’s apparent belief that we can counter the AfD by adapting to their racist ideas is deeply problematic. She has called for more migration controls and attacked anti-racist activists as “scurrilous minorities”. I have written at length about Wagenknecht’s accommodation to racism in the past (see here and here), so won’t add much, except to say that Wagenknecht’s “anti-woke” agenda often dovetails neatly with that of the AfD.

Recently, some on the Left have become enthused about DiEM25, the latest manifestation of the Yanis Varoufakis vanity show. When DiEM25 was formed, they insisted that they would not contest elections, as they intended to be part of the social movements and nothing else. I reported on the DiEM founding conference here, and made a more recent appearance of Varoufakis in Berlin here.

DiEM25 are not programmatically significantly worse than Die Linke, although there is still time for them to degenerate. And yet they do not offer anything qualitatively different. The next election will surely see a plethora of Left organisations campaigning against each other. None of these parties will provide an adequate focus to unite social movements and build the resistance we need.

Can Die Linke be reborn?

Some Leftists agree that Die Linke is not what it used to be, but argue that Wagenknecht’s departure means that the party can be rebuilt on left-wing principles. They point out that party membership has risen since Wagenknecht flounced out, including many pro-refugee activists who refused to engage with a party for which Wagenknecht was a prominent spokesperson and regular chat show guest.

It is certainly true that in my Linke branch, in Wedding, we have had a massive influx of new members, many of whom are well to the Left of the party leadership. We have had lively discussions on Palestine and sent delegations to solidarity demos. But none of this alters the fundamental nature of the party and its obsession with winning elections.

In February, Vashti media claimed that “the Left Party is split between the Wagenknecht group – which consistently opposes militarism but seeks to intensify deportations – and the remainder, which consistently protects migrants”. Unfortunately, this does not remotely reflect reality.

Die Linke has been the majority party in Thüringen for 10 years. Last year, under Linke President Bodo Ramelow, Thüringen deported more than 300 people. Although Wagenknecht’s departure is no political loss, the short term effect has been to strengthen “reformers” like Ramelow whose practise is everything other that “consistently protect[ing] migrants”.

I never thought that Die Linke would be the organisation we needed. From the start, it was an integral part of the electoral process which would always ultimately side with the system. But there were always enough contradictions for it to be a meeting point for people who wanted to go further.

In some places, like my local branch in Wedding and the Internationals group, this is still the case. At the same time, it is no surprise that both Die Linke Wedding and the Internationals are questioning how long we can be part of this rightward drift. In both groups, we have said if we leave we will leave together, and that the unity which we have built is more important than any party structures.

Whatever happens, organisations outside Die Linke are increasingly necessary for carrying on the fight – be this Aufstehen gegen Rassismus for the fight against the AfD, or theleftberlin website. For my part, I still have hopes in the new socialist organisation Sozialismus von Unten, where I am working to bring together German and non-German activists, particularly those who have been radicalised by the Palestine movement.

The situation facing the German Left is grim, but we can’t give up hope. I am convinced that our international experience will be part of what lifts us out of our current malaise. I look forward to seeing more faces in demos, in reading groups, and on the streets of Berlin – with or without Die Linke.