Germany’s voting laws for resident non-citizens add another notable example to the country’s contradictions between its outwardly liberal reputation and its regressive reality.

As many as 8.7 million people could be shut-out of the political system – about 1 in 8 residents. Their only route to enfranchisement lies in gaining German citizenship, which comes with the caveat of renouncing citizenship of any other country. This too comes with an exception for EU citizens, who may hold joint citizenship with Germany. The exception is obviously racialised, and formal citizenship is itself a powerful barrier to the right to vote.

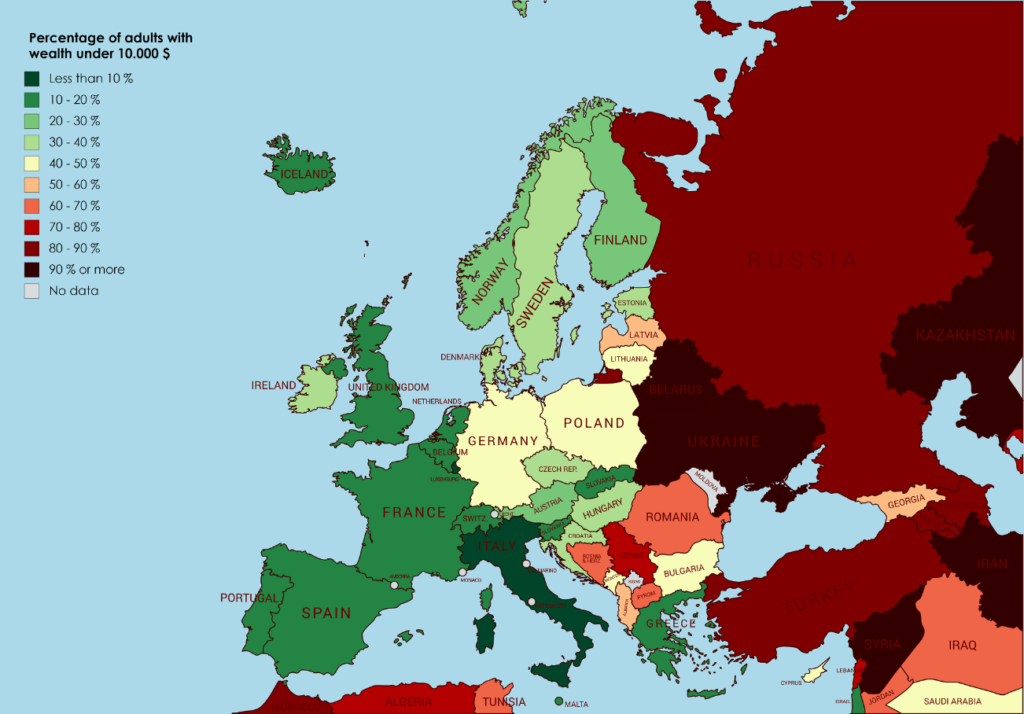

Furthermore, this mass of disenfranchised people is a pillar of the labour force that upholds Germany’s status as Europe’s largest economy despite its ageing population (21.5% of the population is 65+). Mode wealth per citizen in Germany is one of the lowest in Western Europe; 40.6% of adults have wealth under 10,000 USD despite the average wealth per adult being 214,000 USD.

This figure may be partially explained by a lower propensity for home ownership. However, Germany has one of the worst, and underestimated, wealth disparities in Europe. A recent report found that the top 1% owned 35% of all German assets, not 22% as previously thought. These asset owners are generally older, male, and presumably German citizens.

The franchise was the key issue of The Social War, where Rome’s Italian allies were refused citizenship since it would upset the governing balance of political and economic forces prevailing in the city. Only through bloodshed and concessions of citizenship in exchange for ending hostilities did the matter get resolved. The famous slogan of the American War of Independence was “No taxation without representation”. What emerged was a so-called Republic of equals that negated the voice of women and constitutionally enshrined the most vicious slavery. The injustice of taxation without representation prevails today in the neoliberal global economy where borders regulate labour and its rights but allows capital to flow freely.

The explosion in written constitutions occurred in and around the French Revolution. To mobilise an entire nation to war, expanding its scale by an order of magnitude relative to the norm of the early modern period, required codifying the rights of citizens. To forge a nation, the price was blood and the reward was the franchise and the protections that came with it. It was these codified guarantees that allowed Napoleon to raise La Grande Armée, at the time the largest army in recorded history. It was in response to these mobilisations that precipitated other nations to follow suit.

Similarly, the fight for women’s suffrage was won due to the opportunities presented by war. Only when women’s economic and military necessity came to be realised before and during The Great War, did women begin to leverage their essential position in the war economy to bargain for the right to vote. Even then, suffrage spread unevenly and in many parts of the world with caveats. Switzerland did not give women suffrage until 1971.

It is necessary for us on the left to keep these facts in mind when we demand the right to vote for Germany’s immigrants. The challenges of this task demand going beyond making the clear moral arguments and recognising the structural impediments to this moral objective. Eroding these political blockades requires us to recognise our economic power within Germany and to organise ourselves effectively to win the rights we are owed.

Thomas Lacquer laid out in detail how the West German state, unlike the East, never eradicated its Nazism, nor did it adequately compensate its victims. The reunification of East and West operated more like an annexation that allowed the West German state to remain perfectly intact as a legal entity. This legacy plagues Germany today with the far-right becoming stronger, better organised, and more threatening to Germany’s immigrants. The AfD is now a permanent electoral presence and it vocalises a compressed German nativism, yearning to be released.

Establishment parties fear that the AfD can instrumentalise any effort to give immigrants the right to vote. The AfD has a slogan: “Unser Land, unsere Regeln” (Our country, our rules). This is both a threat and an expression of anxiety. Immigrants are threatened to abide by the discipline of Germany’s laws while also being told this country is not theirs. Simultaneously, the AfD expresses a latent fear of losing the power to extract labour without sharing political control.

Well, this is our country just as much as theirs. We immigrants are the struts that keep Germany’s economy upright. We care just as much about the land, about our neighbours, about our shared futures. We deserve a say in the rules that only citizens can affect.

A coalition of German leftists, trade unionists, democrats, and immigrants seeking their rights must be gathered to fight a two-pronged battle. Political organising must work in concert with labour agitation to send a message to a political class that thinks immigrants can be taken for granted.