Last May, I wrote an article about lesser-known Leftist monuments in East Berlin. I promised a similar article on West Berlin very soon. As it happens, I got a little distracted. But, better late than never, here are 10 similar objects worth visiting in West Berlin.

1. Lenin in a car park

Address: Nobelstraße 66

Nearest public transport: Nobelstraße / Bergiusstraße (Bus 246)

In a remote industrial estate in the East of Neukölln, you can find a branch of the removal firm Zapf Umzüge. It looks like any other bland office, except there in the forecourt there is a huge metal statue of Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Russian revolution.

Klaus Zapf, owner of the company, is himself an interesting figure. He apparently moved to West Berlin to avoid military service and became involved in the 1968 student movement. He lived a frugal life, saying “There are just so many bloody idiots with money around – you don’t need another one.”

There are different stories about how Zapf acquired the statue. Maybe it was a loan guarantee from a Russian businessman. Perhaps Zapf Umzüge were commissioned to take the statue to be destroyed, and decided to keep it. Or it could be that it originally belonged to an entrepeneur who got rid of it because of complaints by the neighbours. Probably none of these stories is true.

This is not an area of town where most people casually go, but is well worth the visit.

2. Finding Rosa Luxemburg

Address: Wielandstraße 23 and Cranachstraße 58

Nearest public transport: S-Bahn Friedenau

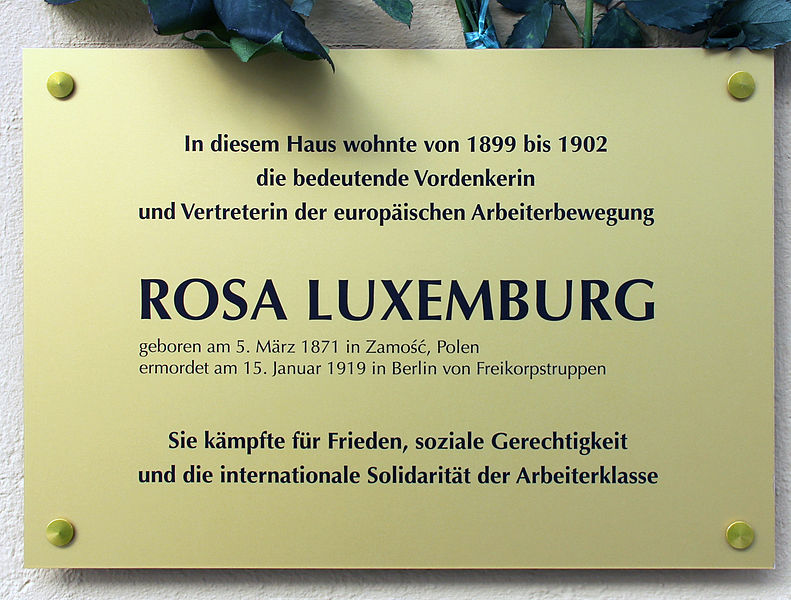

Berlin has enough statues and plaques to Rosa Luxemburg to warrant an entire article. Some are quite famous, like the one in Tiergarten, others are in East Berlin and are outside the remit of this particular article. West Berlin monuments include a plaque to Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht in Mannheimer Straße 27, at the final refuge before they were murdered by paramilitaries working on behalf of the SPD government.

Here, I want to talk about plaques outside two of the many places in Berlin that Rosa lived after arriving from Poland, before the devastation of the First World War and the suppression of the German revolution.

The first plaque, in Wielandstraße, says “In this house between 1899 and 1902 lived one of most important pioneers and representatives of the European workers’ movement. She fought for peace, social justice and the international solidarity of the working class. Five minutes walk away, in Cranachstraße, there’s a sign which is now hidden behind vegetation. The simple text reads “Rosa Luxemburg lived here from 1902-1911. Born 5.3.1871. Murdered 15.11.1919”.

3. Weddinger Blutmai

Address: Walter Rober Brücke

Nearest public transport: U-Bahn Nauener Platz or Pankstraße

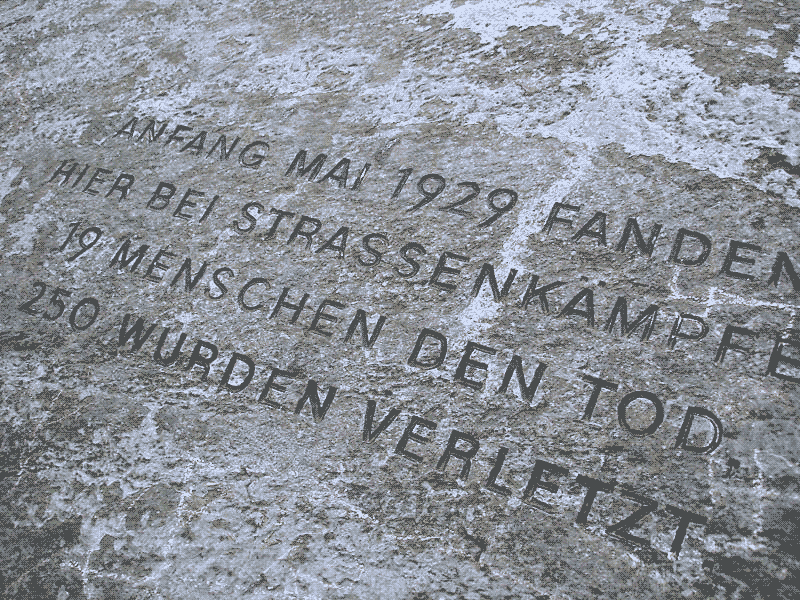

Resistance continued after the German revolution. In 1929, SPD police president Karl Friedrich Zörgiebel banned all demonstrations planned for 1st May. In response, the Communist Party (KPD) called for “Straße frei für den 1. Mai” (streets free for 1st May). Defying the ban, thousands of workers gathered in Berlin – mainly in Wedding and Neukölln – in groups of 50 to 500 people.

Police fired 11,000 shots at demonstrators and local residents alike. One of the first people killed, Max G, was shot when he looked out of his window to see what was going on. In Wedding, the police deployed machine guns against locals throwing bottles and stones. Sources differ as to how many civilians were killed, but most figures lie between 32 and 38. Around 200 more people were injured. After the demonstration, 1,228 people were arrested, although only 43 were convicted.

This massacre had a fatal consequence. In June, the KPD held its Party Congress in Wedding, where they declared the SPD to be a “social fascist” organisation – just as bad as the Nazis. This, combined with SPD anti-Communism led to the failure of the SPD and KPD to unite to prevent the rise of Hitler. The Nazis never had majority support among the German people before taking power.

A commemeration stone for the victims of the Blutmai stands on the Walter Rober Brücke in Wedding with the following inscription: “Street fights took place here at the beginning of May 1929. 19 people were killed, 250 were injured”.

4. Platform 17 (Gleis 17)

Address: Am Bahnhof Grunewald

Nearest public transport: S-Bahn Grunewald

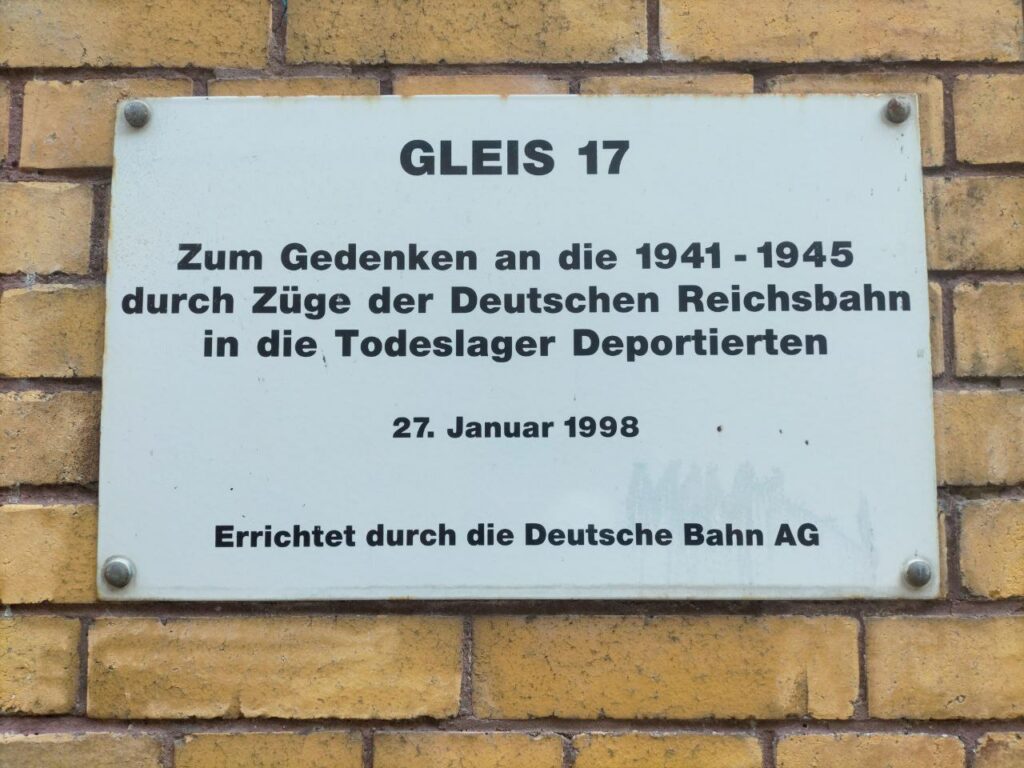

Between 1941 and 1945, more than 50,000 German Jews were deported from Grunewald station to Concentration Camps in the East. Grunewald was chosen because its remote location meant that large numbers could be deported without attracting too much attention. It is also located in a relatively rich area, which was more likely to contain Nazi sympathisers.

On the edge of Grunewald’s Platform 17, next to the train tracks, there are iron grates containing the names of the Concentration Camps to which people were deported, the date of each deportation, and the number of people deported. The first date is 18th October 1941, the last 27th March 1945.

Nearby, there is a monument of a concrete wall, containing the hollows of human bodies, next to a metal panel with the text: “In memory of the more than 50,000 Berlin Jews who were deported between October 1941 and February 1945 mainly from the Grunewald freight station by the National Socialist State to its extermination camps and murdered there”.

5. Deportation Memorials in Moabit

Address: An der Putlitzbrücke, Ellen Epstein Straße, Levetzkowstraße 7-8

Nearest public transport: S-Bahn Westhafen

Not all deportation trains went from Grunewald. From January 1942 until 1945, more than 32,000 Jewish people were sent from the synagogue in Levetzowstraße to platforms 69, 81 and 82 of Güterbahnhof Moabit, from which they were deported.

A 2½ metre high statue stands on the bridge above the railway. The front of the statue shows a gravestone carrying a Star of David. The back shows a broken and deformed staircase to heaven. This monument was damaged by a bomb attack in 1992 and has been repeatedly covered with antisemitic graffiti.

A little further down the tracks, there’s the Gedenkort (memorial site) Güterbahnhof. This contains a monument showing the path taken by deportees from Synagogue Levetzkowstraße. Nearby, part of the train track is still visible. It now leads into a brick wall.

A third monument stands on the site of the Levetzkowstraße synagogue. This shows a goods wagon next to a ramp on which there is an abstract depiction of a group of prisoners. Nearby, there is a huge iron monument on which is written the dates of 63 deportations and their destinations in Eastern Europe. On the ground there are plaques to the synagogues from which they were taken.

6. Commemorating Treblinka

Address: Amtsgerichtsplatz

Nearest public transport: Bus Amtsgerichtplatz (M49, 309, X34), S-Bahn Charlottenburg

Around 900,000 Jews were murdered in the Extermination Camp of Treblinka, East of Warsaw. In 1966, Russian sculptor Vadim Sidur made a memorial to the victims of Treblinka, which was erected in Charlottenburg in 1979.

The sculpture contains four human bodies lying on top of each other, stacked in the form of a cross. The body at the bottom is of a woman who is still alive. Like the Holocaust Memorial near Brandenburger Tor, the statue uses abstract form to depict horror which is virtually indescribable.

Next to the statue, there is the following text in Cyrillic and Latin script: “In the camp Treblinka II, over 750,000 people were murdered between July 1942 and November 1943. If you close your eyes to the past, you will be blind for the present. If you do not want to remember the inhumanity, you’ll be vulnerable to new acts of injustice.”

7. Memorials to the 1953 East Berlin Workers’ Uprising

Address: Berliner Straße 74-76, Seestraße 92-93

Nearest public transport: Straßenbahn Osram Höfe

On 17th June 1953, less than 4 years after the foundation of the East German “workers’ state“, workers rose up against their own government. This confused much of the Left, East and West, many of whom thought the uprising was a CIA plot. I have written elsewhere about how Berthold Brecht was similarly conflicted. In East Berlin, no memorial was erected before 1990.

In the West, however, the uprising was used for Cold War propaganda. Less than a week after the uprising, the Berliner Senat decided to rename the street which leads to the Brandenburger Tor Straße des 17 Juni. Western leaders, who did everything they could to put down workers’ struggles in their own country, suddenly became great fans of insurrection.

In Berliner Straße 74-76 in Reinickendorf, there’s a small memorial to demonstrating steel workers from Hennigsdorf. Not far away, there the Urnenfriedhof Seestraße in Wedding. At the entrance of the cemetery, you see both commemorations to Germans who died in the Second World War and a larger monument to 295 victims of National Socialist [Nazi] dictatorship.

But if you go 100 yards forwards, you see a monument accompanying the graves of the 8 victims of Russian bullets who died in West Berlin hospitals. Like all Western monuments commemorating the 1953 uprising, it is contradictory, but the fight that it remembers was a noble one.

8. Death of a Protestor

Address: Bismarckstraße 35

Nearest public transport: U-Bahn Deutsche Oper

On 2nd June, 1967, Christian pacifist student Benno Ohnesorg attended his first political demonstration. It was outside the Deutsche Oper, where the Shah of Iran, Reza Pahlavi, was attending a performance of the Magic Flute. Demonstrators were attacked by both SAVAK, the Iranian intelligence service, and the German police. Ohnesorg was shot and killed by the police.

10,000 people attended Ohnesorg’s funeral where student leader Rudi Dutschke made the following address: “June was a historic date in the German universities. For the first time since World War Two huge strata of students mobilised against the authoritarian structure of this society. They experienced this irrational authority during the demonstration.” The West German 1968 started in June 1967.

In 1971, Alfred Hrdlicka created the sculpture “Death of a Protestor”, which is currently opposite the Deutsche Opera building. Next to the sculpture there is a plaque which contains the following text about Ohnesorg: “His death was a signal for the nascent student and extra-parliamentary movement, which particularly linked their struggle for radical democratisation in their own country with those against exploitation and oppression with those in the Third World.”

9. Ulrike Meinhof’s grave

Address: Eisenacher Straße 21

Nearest public transport: U-Bahn Westphalweg

After the SPD won the 1969 General Election, the 1968 movement started to retreat from the streets. The SDS student organisation had already effectively disintegrated after its conference the previous December, and apart from a few fleeting strikes, resistance dropped.

Frustrated by the decline in militancy, some young activists turned to terrorism, most notably in the Baader-Meinhof Group (aka Red Army Faction, RAF). The RAF understood itself as a communist, anti-imperialist urban guerilla group engaging in resistance against a fascist state. The media named the group after two if its leaders – Andreas Baader and left-wing journalist Ulrike Meinhof.

The RAF was best known for a bombing and kidnapping campaign in the 1970s. Support extended way beyond the radical Left, especially in student circles, including even my German teacher, later a member of the Conservative CDU.

In 1975, the “first generation” RAF leaders were tried in Stammheim prison. Meinhof died of hanging in her cell in 1976, Baader of gunshot wounds in 1977. Other group members also died in jail, all allegedly by suicide, although this was hotly disputed. 7,000 people attended Meinhof’s funeral, and Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir led the protests against her death.

Most Berlin cemeteries contain a plan near the entrance showing where you can find the famous (and some not so famous) people buried there. Not so, the Dreifaltigkeitsfriedhof III in Schoeneberg. In a seldom visited part of the graveyard, with no great ostentation, there is a simple gravestone bearing the words “ulrike marie meinhof 7.10.1934 – 9.5.1976.”

10. Korean Peace Statue

Address: Bremer Straße 41

Nearest public transport: U-Bahn Birkenstraße

The Peace Statue in Moabit is a memorial to the so-called “Comfort women” – girls and women who were forced to act as prostitutes in Japanese brothels during the Second World War. It is intended as a symbol against all sexual violence. An estimated 200,000 women and girls were raped and forced into sexual slavery during the Asia-Pacific wars of 1931-45.

The bronze statue, by South Korean artists Kim Seo Kyung und Kim Eun Sung, was erected on 28th September 2020. It shows a girl in a Korean dress, sitting next to an empty chair. The girl casts a shadow in the shape of an old woman. The statue also depicts a bird of peace and a white butterfly, symbolising rebirth.

On the day after the statue was erected, the Japanese cabinet secretary and government speaker Katsunobu Kato called on Germany to remove the statue. Japan’s foreign minister Toshimitsu Motegi made a similar demand to his German counterpart Heiko Mass. The Korea Verband, which is responsible for the statue, was ordered by the district authority in Berlin-Mitte to remove the statue by 14th October 2020. Resistance, including demonstrations in Moabit, have kept the statue in Moabit.

You can read more about the Peace Statue in this interview.