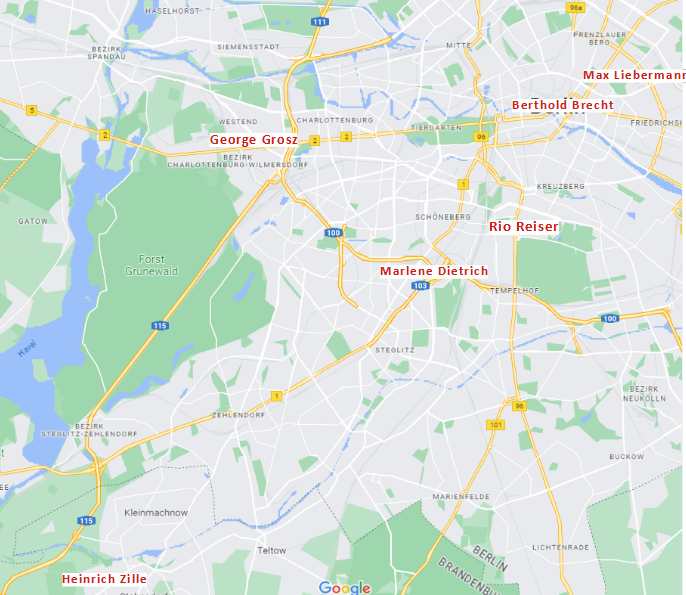

In a recent article, I listed six cemeteries in Berlin where you could find commemorations to important left-wing resistance. In this follow up article, here are six, well seven, further cemeteries where you can visit the graves of radical artists.

Max Liebermann (1847-1935)

Max Liebermann was the son of a banking millionaire. He was a patriot, who volunteered for military service during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1. At the beginning of the First World War, he co-signed a statement by academic and artists denying German war crimes. During the war, he produced pro-war propaganda for the newspaper “Kriegzeit – Künstlerflugblätter.”

Justifying his position, he said: “At the beginning of the war you didn’t think twice about it. People were united in solidarity with their country. I know well that the socialists have a different view… I’ve never been a socialist, and you don’t become one anymore at my age. I received my entire upbringing here, and I spent my entire life in this house, which my parents already lived in. And the German fatherland also lives in my heart as an inviolable and immortal concept.”

At the same time, he was a Jew in a country where antisemitism was rife. He died in 1935, 2 years after General Hindenburg – whose portrait he painted in 1927 – offered Hitler the German Chancellorship. His daughter Käthe managed to escape the country. His wife Martha was not so lucky. She committed suicide in 1943, awaiting deportation to Theresienstadt Concentration Camp.

Was Liebermann a radical? He was certainly a radical artist, the leading German member of the Impressionist movement. His first exhibit, “Women Plucking Geese” was denounced for depicting people at work. One critic called him the “disciple of the ugly.” In 1898 he was part of a jury which tried to award a medal to Käthe Kollwitz for her etchings based on Gerhart Hauptmann’s “The Weavers”. They were prevented by German Emperor Wilhelm II who refused to honour a woman.

Both Max and Martha Liebermann are buried in the Jewish Cemetery at the bottom of Schönhauser Allee. Only 38 mourners signed the condolence book at his funeral. State dignitaries and officials stayed away – the only non-Jewish exceptions were Dr. Ferdinand Sauerbruch, another of Liebermann’s sitters, and Käthe Kollwitz.

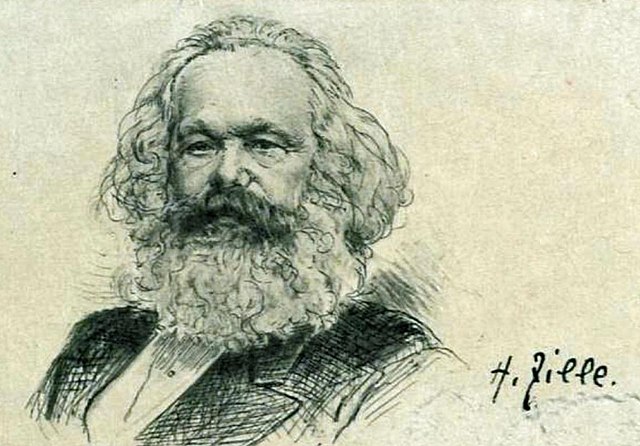

Heinrich Zille (1858-1929)

Heinrich Zille was not an activist, but after his death both the Socialist and the Communist Parties claimed him as one of their own. Zille’s viewpoint though may be best summed up by his biographer H Ostland: “He did not believe in fair words, propaganda, talk and speeches. He was in favour of action. Which in his case meant his own work”. Although he occasionally published in the socialist press, most of his works were first published by liberals.

Zille grew up in poverty, and when he started to gain a living as an artist, he sketched what he knew – Berlin’s Mietskasernen (tenement slums), and in particular working class women and their children. Unlike some artists, who painted portraits of well-paying noblemen (and the occasional noblewoman), Zille drew the poor. His most important collections include “Mein Milljöh” (my milieu) and Kinder “der Straße” (street kids).

Zille’s satire was not confrontative, or explicitly political. In contrast to more active artists like his friend and contemporary Käthe Kollwitz. This does not mean that he was politically neutral. The caption for his picture ‘Geburtenrückgang’ reads “I’ve got six children in the cemetery, isn’t that some effort for the Fatherland?” But he preferred to draw people at home rather than working in factories, showing individual suffering much more than communal resistance.

Zille’s art was the product of his times – which included the First World War, which he opposed, and the Spartacus uprising. He died in 1929, 4 years before Hitler became German Chancellor. The Nazis tried first to denounce Zille as a “socialist public pest”, then, when he proved too popular, argued that he depicted the old degenerate world which they had replaced.

Zille was a fellow traveller – a pacifist and a socialist of sorts. He was far more interested in working people than in the riches of power. Socialist author Kurt Tucholsky called him “Berlin’s best”. He was one of us. He is buried in the Südwestkirchhof in Stahnsdorf on the edge of Berlin. You can still see many of his pictures in the Zille museum in the Nikolaiviertel near Alexanderplatz.

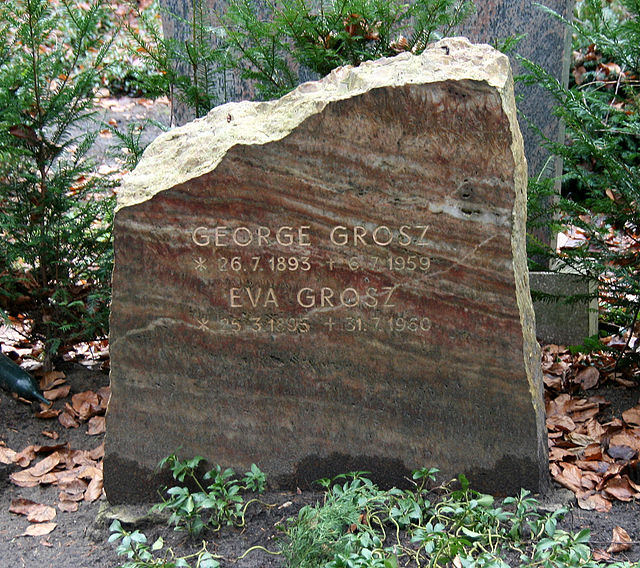

George Grosz (1893-1959)

In contrast to Liebermann and Zille, George Grosz was much more politically committed. In 1916, in the middle of the First World War, Grosz and his friend Helmut Herzfeld changed their names to challenge the dominant mood of German nationalism. Grosz changed his first name from Georg to George, while Herzfeld became John Heartfield, and was to pioneer the art of photomontage during the Weimar era.

As war led to the November Revolution, Grosz joined Rosa Luxemburg’s Spartacist League at the end of 1918. He was arrested during the Spartakus uprising the following year. His was also artistically radical. He was a founder of the Berlin Dada movement, and his paintings and sketches, full of prostitutes, drunkards and corrupt businessmen, showed the seedy underbelly of Weimar Germany. Many of his pictures featured men who had been crippled in the war.

In June 1932, with Hitler’s power seizure imminent, Grosz fled to the USA. He felt liberated by his new environment, saying: “The air in Manhattan had something inexplicably exciting about it, something that spurred my work onwards … I was filled with light and colours and joy”. He changed his artistic style, concentrating on landscapes, nudes and watercolours. It may be a cliché, but most of Grosz’s best works were made when he was less content.

In the USA, he also seems to have softened his politics. He took US citizenship in 1938 and was unwilling to criticize the country which offered him a sanctuary from Nazism. In his autobiography, written in 1946, he rejected his youthful radicalism, saying “I made speeches, not really from conviction but rather because there were people standing round all day long arguing and my previous experiences had not taught me any better.”.

In 1959, a few weeks after he had returned to Berlin, Grosz died after falling down a flight of steps while drunk. He is buried in the Friedhof Heerstraße opposite the Olympiastadion. Whatever he wrote in his later years, for a while, he was both a great artist and an influential political figure.

Berthold Brecht (1898-1956)

Berthold Brecht is one of the twentieth Century’s most important playwrights and poets, the lyricist for a British Number One record (Bobby Darin’s Mack the Knife) and a Hollywood scriptwriter. He was also a lifelong Communist and a member of the group who were to become the Hollywood Ten.

Brecht’s breakthrough came with the “Threepenny Opera” – the “play with music” which he co-wrote with Kurt Weill in 1928. In 1933, he fled Nazi Germany, first to Sweden, later to the USA where he wrote the script to Fritz Lang’s film Hangmen Also Die. Alongside his better known plays like “Mother Courage and her Children”, and “The Life of Galileo”, he also attempted to rewrite the Communist Manifesto as a hexameter poem.

In 1947, Brecht was forced to testify before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, Senator Joseph McCarthy’s kangaroo court aimed at purging Hollywood (and other US industries) of left wing radicals. Brecht answered all the court’s questions, while saying nothing, then immediately fled to Europe.

He moved to East Germany, which he saw as the “least bad” option, but was not uncritical of the DDR. When workers rose up East Berlin, Brecht wrote the poem “The Solution.” This famously ends with the lines: “Would it not in that case Be simpler for the government To dissolve the people And elect another?” He then put the poem in a drawer and it was not made public until after his death, 3 years later.

Brecht’s major contribution was probably to dramaturgy, with ideas like the Alienation Effect and Epic Theatre, he argued that theatre should confront its audience’s assumptions. In the 1930s he engaged in a number of debates with the Marxist critic Georg Lukács about the relative worth of Expressionism and so-called “Socialist Realism”.

Brecht is buried in the garden of the house which he lived in in East Berlin, which was already home to the grave of philosopher GWF Hegel. Other important left wing cultural figures have since been buried in the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, including the photomontage artist John Heartfield, philosopher Herbert Marcuse and dissident author Christa Wolf.

Marlene Dietrich (1901-1992)

Marlene Dietrich spent Weimar Germany boxing and enjoying Berlin’s gay clubs. She became a star after her performance in “The Blue Angel” in 1930. It was her twentieth film, but the first one with sound. In the film – released in both German and English – Dietrich plays a sensuous cabaret singer who features in smutty postcards. It is said that Hitler destroyed all copies of the film, apart from one which he kept for himself.

After the success of the Blue Angel, Dietrich moved to the USA. In her first Hollywood film, Morocco, she wore a tuxedo and top hat, and kissed a woman on the lips. She refused to work in Nazi Germany, although the Nazis approached her and offered to make her the “pretty face” of the Third Reich. In 1937 she was approached once more and asked to star in Nazi propaganda films. She refused again, and later renounced her German citizenship.

In the 1930s she set up a fund with director Billy Wilder to help Jews escape Germany. The Nazi paper “Der Sturmer” denounced her, saying that “the film Jews of Hollywood” had made her “un-German”. After the war, when she learned that her sister had run a cinema which was frequented by guards from Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, she disowned her sister (while allegedly making sure that she didn’t starve).

Dietrich did not just offend the German government. In 1933, she was told that she would be arrested if she wore trousers in Paris (women wearing trousers was only officially legalised in France 10 years ago, fact fans). A couple of years ago, a picture of her supposedly being arrested went viral, although the picture is just of her getting off a train, and the arrest never happened.

Dietrich is buried in the Friedhof Friedenau, the so-called “artist’s cemetery” in Tempelhof-Schöneberg. She was an anti-fascist, a bisexual and a strong woman at a time when women were supposed to keep quiet and know their place. After attacks on her grave, her grandson proudly announced: “She’s still fighting”.

Rio Reiser (1950-1996)

In 1970, Rio Reiser helped form the band ‘Ton Steine Scherben’ (TSS), which played squats and demonstrations while becoming remarkably successful. In the 1970s alone, TSS sold 300,000 albums, despite their refusal to advertise and radio stations’ reluctance to give them airplay. Their first gig was at the Festival der Liebe which also featured Jimi Hendrix. Their performance ended with the stage going up in flames.

Unlike most of their German contemporaries, TSS played songs in German, because they wanted to connect with German workers. Reiser once said that the band moved to Kreuzberg as they heard that young proletarians lived there. They released their own fanzine, “Guten Morgen”, which covered women’s and gay liberation, Black Power and the RAF’s guerrilla struggle in West Germany.

TSS’s first single “Mach kaputt was Euch kaputt macht” (Destroy what destroys you) was a song that Reiser had written in the 1960s for Hoffmans Comic Theater, an agit-prop group which toured schools. Other songs like the Rauch-Haus-Lied came out of his active involvement in the squatters’ movement. Following the police murder of activist Georg von Rauch, TSS played at a teach-in, which resulted in the occupation of the Bethanien buildings in Mariannenplatz,

Like Rudi Dutschke, Reiser was a practising Christian. He told his friends that he was gay in 1970, although he did not come out publicly until the 1980s. He was slightly suspicious of the student movement, which he found “too much like school”. Nonetheless he was an active member of the movement which developed after 1968. In 1970, the band was expelled from Switzerland after a concert in Basel turned into a political demonstration.

In 1975, the band moved from their commune in Berlin to a farm in Schleswig-Holstein. Reiser died in 1996 and was buried on the farm. In 2011, after the farm was sold, his grave was moved to the Alter St. Matthäus Kirchhof. Reiser now lies close to the Brothers Grimm. His memory lives on. A square in Kreuzberg was recently named after him, and if you go to a party organised by Berliners of a certain age, the evening is unlikely to end before you’ve all sung along to old TSS songs.