Berlin has a long and radical history. In the past 200 years, it has experienced 3 revolutions, 2 World Wars, fascism, “state socialism” (which had little to do with actual socialism), and a flourish of ground-breaking art (most notably during the Weimar period in the 1920s). Berlin’s graveyards are, therefore, full of radicals who left their mark on the city.

This is the first of 2 articles aiming to give you a brief introduction to some of the people and events which shaped Berlin. This article concentrates on historic events, while the second will introduce some radical artists who are buried in the City.

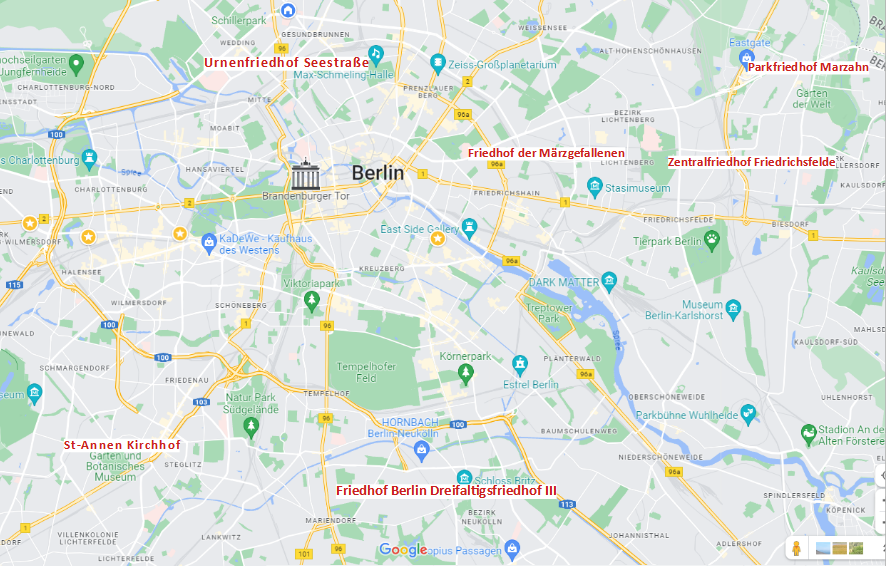

The 1848 Revolution (Friedhof der Märzgefallenen)

1848 saw the first Europe-wide movement for freedom, democracy and social justice. A wave of revolutions demanded civil and political rights for the growing middle class. Towards the end of February, demonstrations in France led to the abdication of King Louis-Philippe. The next month, Austrian chief minister Prince von Metternich was forced to resign.

On March 13th – the same day as the demonstrations which brought down Metternich – the army in Berlin killed one person coming home from a meeting. Five days later, thousands of people took to the streets and put up barricades. 270 people were killed in the fighting. Most of the dead were young and poor. They included 11 women and 10 children.

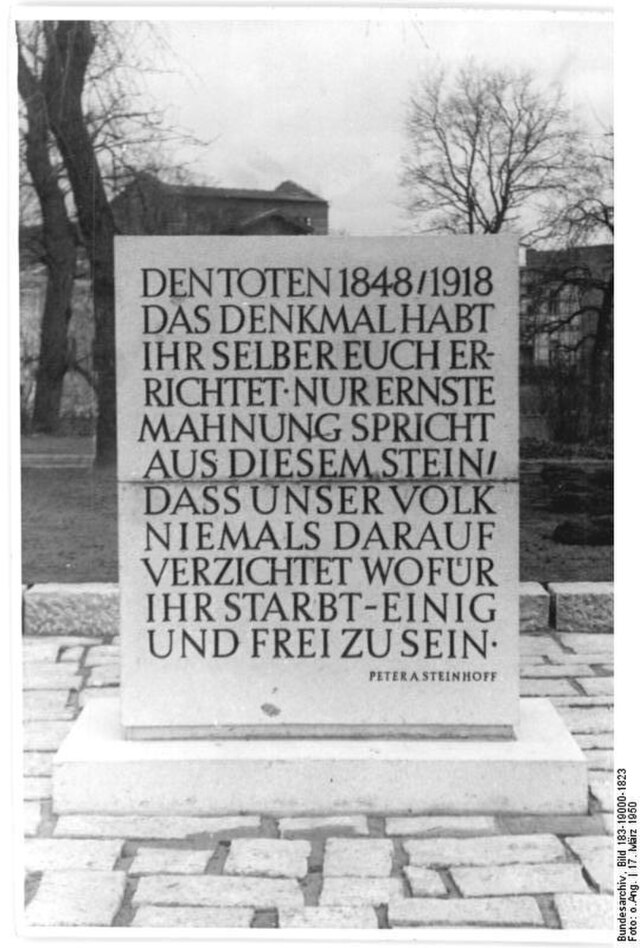

On 22nd March, a “state funeral from below” was held at Gendarmenmarkt. 100,000 people attended – a quarter of the population of Berlin. 183 coffins were taken to the “Friedhof der Märzgefallenen” in the Volkspark Friedrichshain. In 1919, an extra 33 Berliners who were killed in the November Revolution were also buried here.

At first, it seemed that the March revolution had achieved its aims. Prussian king Frederick William IV – who had watched the “state funeral” from his balcony – agreed to the demonstrators’ demands, including parliamentary elections, a constitution, and freedom of the press. He also approved arming the citizens and releasing Polish prisoners.

But by late 1848, the army had regained power. The king dissolved the Prussian National assembly in November, and introduced his own constitution. An assembly was set up, but voting rights were very much dependent on how much money you had. 20% of the male-only electorate voted for two-thirds of the representatives.

Propertied Middle class men had shown that they were prepared to fight for their liberties, but not for those of their “underlings”. German workers had to wait another 70 years until they were able to take part in a revolution of their own.

The Matrosen Uprising of 1918 (Parkfriedhof Marzahn)

In 1918, Germany was war-weary. The First World War had been dragging on for four years, and the original enthusiasm was waning, particularly among those on the front. In August 1917, 350 sailors on the Prinzregent Luitpold demonstrated in Wilhelmshaven. Their leaders were jailed or killed by firing squad. The response of the other sailors was to build secret workers’ councils.

On 24th October 1918, Admiral von Hipper ordered the fleet into the English Channel. The war was already lost, but he thought that this suicidal act could improve Germany’s position at the post-war bargaining table. This caused a mutiny – first in Wilhelmshaven, later in other ports. The mutiny was put down and more people were imprisoned, but resentments continued to grow.

On 1st November, 250 sailors and stokers met in the Union House in Kiel, demanding the mutineers’ release. The police closed the building. Thousands attended a meeting the following day. More demands were added, including better food. As the demonstrators moved towards the prison, soldiers shot at them, killing seven. Protestors retaliated. The German Revolution had begun.

On 4th November, sailors’ and workers’ representatives met once more in the Union House. They formed a soldiers’ and workers’ council, which issued 14 demands known as the Kiel Fourteen Points. These included the release of all political prisoners, no launching of the fleet, and the removal of all officers who did not support the newly formed soldiers’ council.

The Parkfriedhof Marzahn contains a memorial to the revolutionary sailors, and the graves of the brothers Fritz and Albert Gast. After a failed general strike, the Gast brothers – mutinying sailors who had also taken part in the Spartacus Uprising – were murdered, along with 9 other workers, by right wing Freikorps troops.

The 1919 German Revolution (Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde)

The uprising of the Kiel sailors provoked similar demonstrations across Germany. Workers and soldiers took control of several cities, including Bremen, Hamburg, Hanover, Cologne, Leipzig, and Dresden. On 9th November, as soldiers and armed workers marched through Berlin and the Kaiser fled the country, Karl Liebknecht – who had only recently been released from prison – proclaimed a new socialist republic.

Almost simultaneously, SPD minister Philipp Scheidemann proclaimed a much more bourgeois republic from the balcony of parliament. Newly appointed Chancellor Friedrich Ebert contacted the army generals, who agreed to work with the new social democratic government to restore order and put down the revolution.

SPD leaders provoked the premature Spartacus uprising, and then sent in right wing troops from the Freikorps, who would later develop into Hitler’s storm troopers. Liebknecht was arrested and shot in the back of the head while “attempting to escape.” His fellow revolutionary leader Rosa Luxemburg had her face smashed in by a rifle butt and her body was thrown into the Landwehrkanal. The social democratic press falsely claimed that she’d been killed by an angry mob.

Events in 1918 and 1919 concluded an apparently abstract debate which Luxemburg had been having with SPD theoreticians like Eduard Bernstein and Karl Kautsky. Whereas Bernstein and Kautsky had advocated piecemeal reform, Luxemburg insisted that “people who pronounce themselves in favour of the method of legislative reform in place… of social revolution, do not really choose a more tranquil, calmer and slower road to the same goal, but a different goal.”

History proved that Luxemburg won the theoretical argument, but she paid for it with her life- Ebert’s counter-revolution arguably paved the way towards Hitler being offered the Chancellorship in 1933. Luxemburg is buried in the Zentralfriedhof Friedrichsfelde, alongside Liebknecht and many other revolutionaries including artist Käthe Kollwitz, DDR leader Walther Ulbricht, and leading Communist Ernst Thälmann who was murdered in Buchenwald concentration camp.

1953 Berlin Workers Uprising (Urnenfriedhof Seestraße)

In March 1953, the state run East German trade unions agreed to a “voluntary” increase in work quotas. Work was increased, and real wages fell by as much as a third. On 16th June, building workers held a sit-down strike opposing these attacks on their living and working conditions. As they marched towards the party headquarters, workers from other building sites started to join them.

What started as a purely economic strike started to develop political demands. The protestors chanted the slogans: “Workers Join Us! Unity is Strength! We Want Free Elections!” On 17th June, strikes broke out throughout East Germany, in at least 700 cities and villages. The strikes involved an estimated 1 million workers, or 10% of the population. School students struck and prisons were stormed.

25,000 Russian troops were sent into Berlin to put down the uprising. Martial law was declared, and all gatherings of more than 3 people were banned. Strike leaders were imprisoned, and some were executed.

The causes of the 1953 uprising have been disputed on the Left. In particular, people who saw the Eastern Bloc as not quite as bad as the capitalist West insist that the insurrection was organised by the CIA to destabilise the new Eastern Bloc. I don’t agree. I’ve written more in an article about Berthold Brecht’s reaction. I believe that workers are capable of organising themselves whether or not their bosses claim to be socialists.

Remembering the insurrectionists has become akin to a game of political football. The street which runs from the West was almost immediately renamed the Straße des 17. Juni. This had nothing to do with supporting workers fighting exploitation and everything to do with Cold War politics. The Urnenfriedhod Seestraße is a little more nuanced. Workers who died in 1953 are buried close to those who resisted the Nazis. We should reject the propaganda and celebrate their struggle.

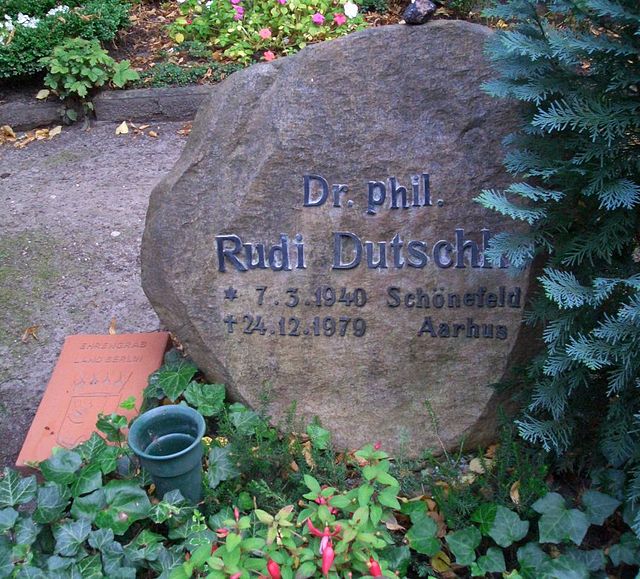

Rudi Dütschke, 1968 and the SDS (St-Annen Kirchhof)

1966 saw the election of a Grand Coalition between the SPD and CDU, led by former Nazi-Party member Kurt Georg Kiesenger. The following year, on 2nd June, the Shah of Iran visited West Berlin, provoking a huge counter-demonstration. Police shot at demonstrators, killing Benno Ohnesorg who was attending his first ever protest. Karl-Heinz Kurras, the policeman who shot Ohnesorg in the head, was later acquitted of any crime.

10,000 people attended Ohnesorg’s funeral, led by student leader Rudi Dutschke. A radical youth movement started in Berlin – partly because West Berliners were exempt from military service. This movement quickly spread throughout Germany. In February 1968, the SDS – the student organisation of which Dutschke was a prominent member – organised an international Vietnam conference in West Berlin which attracted activists from across Europe.

The right wing Springer press made Dutschke public enemy #1, with Bild Zeitung running headlines like “Stop Dutschke Now”. On 11 April, Dutschke was shot and nearly killed by a right winger. The student movement responded with mass demonstrations, including 40,000 in Berlin on 1st May Just over a week later, student protests in France were accompanied by a mass strike of 10 million workers.

For a short period, the movement started to generalise. In summer 1968, West German trade unions called demonstrations protesting against the new Emergency Powers Act. In 1969, an SPD government was elected which put pressure on unions to dampen down militancy. While strike days in 1967-71 were 161 per 100 workers in Italy and 350 in France, in West Germany the figure was only eight.

The SDS collapsed in late 1968. Dutschke rebranded himself a “patriotic socialist” and – like many of his contemporaries – joined the Green party. He died in 1979 of complications from his shooting. He is buried in St Annen churchyard, not far from the Free University where he studied.

Ulrike Meinhof and the Red Army Faction (Friedhof Berlin Freifaltigsfriedhof III)

What do you do when a massive social movement dies down? This was the question confronting many German Leftists in the early 1970s. In 1970, the Red Army Faction was formed, quickly dubbed by the press as the Baader-Meinhof group after two of its leading members: petty criminal Andreas Baader and radical journalist Ulrike Meinhof. They started by setting fire to two department stores in Frankfurt-Main before going on to assassinations and bank robberies.

Meinhof articulated the RAF’s strategy: “If one sets a car on fire, that is a criminal offence. If one sets hundreds of cars on fire, that is political action.” This sounded radical, but was quite different to the attempts of the French student left to unite with striking workers. In Germany, the number of people on the street was already receding, and in the absence of a mass movement, the RAF tried to substitute themselves.

The German state started to win back the upper hand, passing the Radikalerenerlass in 1972 – a law banning left wingers from public sector jobs. In the same year, the main leaders of the RAF, including Meinhof, were arrested, and later sent to Stammheim Prison near Stuttgart. The RAF prisoners went on hunger strike, but were no longer able to appeal for the support of a mass movement.

On 9th May 1976, Meinhof was found hanged in her prison cell while she was awaiting trial. Her death was reported by the authorities as a suicide, but not everyone was convinced. On 17th October, all other imprisoned RAF leaders met a similar fate. Baader was reported to have shot himself in the back of the head – prompting Martin Rowson’s cartoon captioned: “Andreas Baader adds being double-jointed to his other crimes against the West German state”.

At the entrance of many Berlin cemeteries. you see a list of the famous (and less famous) buried in their grounds. You’ll see no such list in the Freifaltigsfriedhof. Ulrike Meinhof lies there almost unnoticed among the other bodies. You may disagree with her strategy but she represents Germany’s post-1968 idealism and a desire to change the world. She deserves better than this.