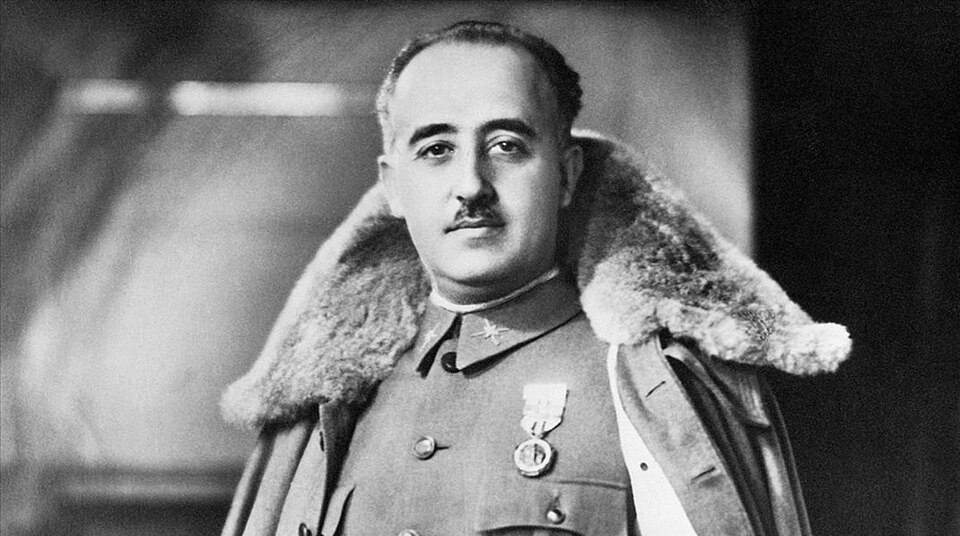

Fifty years after the dictator’s death, Spain remains marked by the impunity of the Franco regime. The social movements that fought for decades against the dictatorship took to the streets during the so-called “transition”, only to face brutal repression from a state apparatus that was never purged of its fascist elements. This period was not the peaceful transition often portrayed, but one of intense social struggle met with state violence.

Various movements led this fight. Workers demanded fair labour laws against a Francoist elite; women fought for fundamental rights in the face of entrenched patriarchy; and the LGTBIQ+ movement confronted legislation that criminalised their identity. Students, youth groups, and neighbourhood associations simultaneously fought for educational freedom, voting rights, and housing justice, creating a powerful political fabric.

In contrast to these hard-won social advances, the political reforms were largely cosmetic. The 1977 amnesty law cemented impunity for the regime’s officials, exonerating judges, police officers, and torturers with the stroke of a pen. Key institutions, such as the repressive Public Order Court, were simply renamed, giving rise to what is critically known as the “Regime of ’78”.

This inherited impunity is still visible today. Francoist symbols and streets named after fascist leaders persist due to a profound lack of political will, not legal obstacles. The state’s effort to exhume the tens of thousands of disappeared from mass graves has been grossly inadequate, leaving civil society groups to lead the search for truth and identification.

This whitewashing extended into education, where for decades the dictatorship was sanitised as the “Franco era” and the 1936 coup was not even named as such. It was a deliberate strategy by Spanish elites—many of whom owe their fortunes to the dictatorship’s corruption—to hide the regime’s crimes and avoid accountability.

The economic legacy of the regime also endures. Major Spanish companies, such as the energy giant Naturgy, were built on the violent expropriation of property from those murdered by the regime. Francoist concentration camps, though not designed for industrial extermination, nevertheless served as instruments of political terror and forced labour, intended to crush opposition and instil lasting fear.