As the city of Berlin continues to be gentrified, the number of people affected by the housing crisis in Berlin is rising. Even though more than 50 percent of Berlin residents with voting rights voted for Deutsche Wohnen und Co. to be expropriated, nothing has transpired. The politicians have not only failed to stop gentrification or find any kind of long-term solution for solving the housing crisis, but have also contributed to the criminalization of the people who are most affected by the crisis: undocumented people, people without housing, migrants, BiPoCs, unemployed people, and people without German citizenship (who, by the way, do not have voting rights).

3.75 Million Euro = one year of rent for 780 people

Since March this year, the SPD have invested 3,75 Million euros in building a police watchtower at Kottbusser Tor, which is historically and politically one of most important neighborhoods for migrants, workers, and so-called “guest workers” in Berlin. The planned surveillance facility at Kotti is supposed to “guarantee the security of the residents ” but will only open new avenues to criminalize marginalized people and commit racial profiling and police violence In Kreuzberg.

All this is taking place while Kotti remains one of Berlin’s “KBO- Kriminellbelastete Orte”, a status which legally gives the police the authority to control anyone at any time without any reason. Like all the other KBO, the victims of the police watch at Kotti will be in the first line of people who will be racially labeled as “dangerous”: black, indigenous, people of color, and especially undocumented people.

3.75 million euros is enough money to pay 780 people’s rent for one year or to start new housing construction projects, schools, and care centers for children and the elderly. So instead of even trying to solve the gentrification problems by tackling economical issues, the government is turning the migrants and people with low income out of their neighborhoods: happily and legally gentrified ever after.

Who gets to build a home in Berlin?

It’s no secret that Berlin’s housing market is deeply classist and racist. When applying for an apartment, the most important factors are your income, name, race, and nationality. The situation is, of course, far more complicated for (documented) people whose former residential address is a refugee camp, outside of Germany, or a homeless shelter. This power dynamic doesn’t limit itself to apartment-hunting; it’s more or less the same situation with finding rooms in shared flats.

Everyone who has suffered from the housing crisis in Berlin is aware of the power imbalance between the Hauptmieter (main tenant) and untermieter (subletters of the other rooms), even within a small household. As a result, many people end up in precarious, overpriced or insecure living conditions. For marginalized people, the right to have a home can always be questioned or taken away, and the need for a home can be instrumentalized to reinforce systems of unequal power imbalances. How can we change this?

Resources(s)-sharing as political praxis

Everyone complains about cis white men, yet they are the ones who get to have a place to sleep at night. When it comes to choosing a flatmate, white middle-class subletters share their “resources” with other white middle-class people.

Systematic racism and class discrimination means not only having no chance to certain but also ascertain social capital. It means being barred from getting an apartment or a room to rent due to low income, name, race, or citizenship, and also, crucially, having less access to the people who do have access to those resources and who, as a result, are less likely to share them. This gap is reflected in social groups (even my own), and is one of the reasons why the housing crisis threatens marginalized communities to such an extent that it can lead to homelessness.

So should we just rent our room and the problem will be solved?

Yes. And No. Of course, the housing crisis will not be solved by individuals who are ready to share their limited resources. This is not an invitation to take on the state’s responsibility instead of demanding structural change.

What is needed are networks of solidarity that reflect one’s political possibility and try to actively break the cycle of power dynamics. When the state fails to produce at any kind of solution for the most basic human right to live, it is the responsibility of its citizens with more access to find alternative solutions.

This does not and should not mean we should take the responsibility of the government and massive investor companies and try to find individualized solutions within our limited resources. Quite the opposite: we should keep fighting and demanding equal access to housing for everyone while finding different points of access to political power to make changes. And this is one of the biggest challenges in many leftist movements.

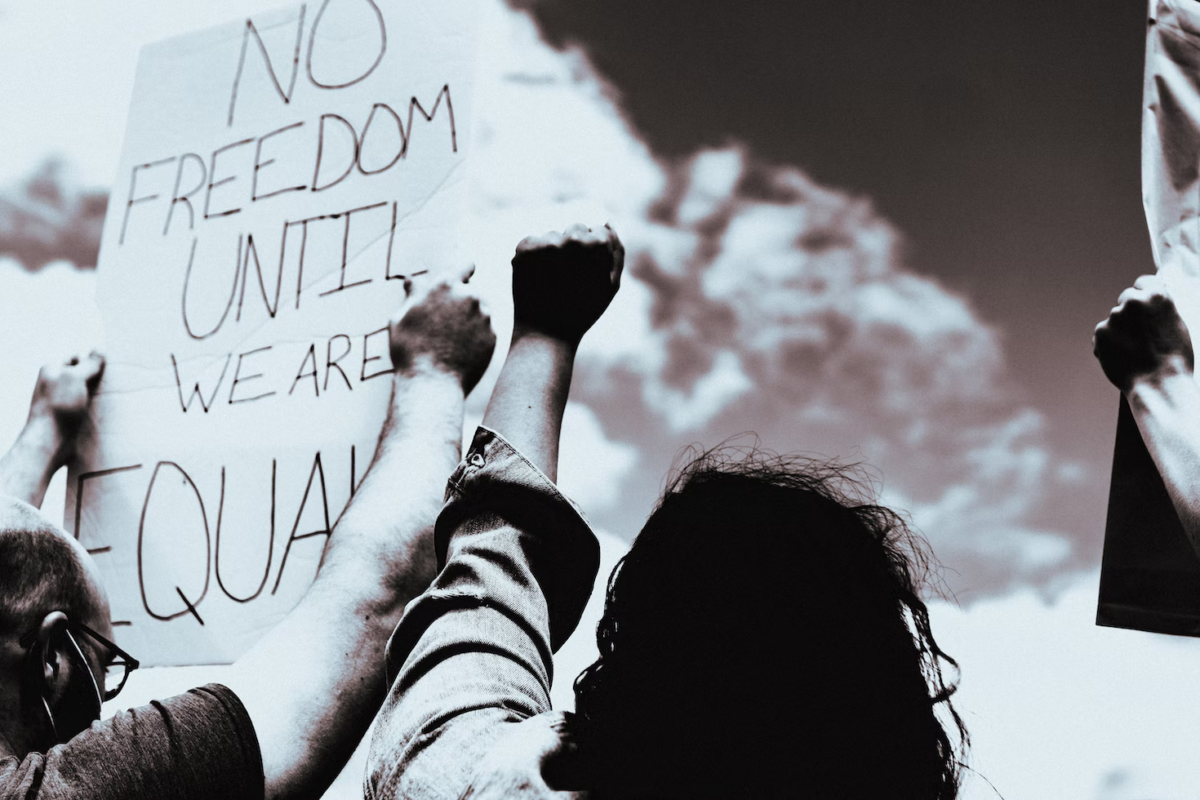

There need to be short-time strategies in place to minimize the harm and pressure on minorities and the most intersectionally marginalized groups while fighting for the broader change: After protesting on the street for housing rights, a person should have a place to go to sleep. There should be measures to provide safety for people without documents or migrants during such protests. To include and unite movements and people, we need to prioritize the needs of the most marginalized group(s)..

Resources(s)-sharing as an alternative to classical governing hierarchies:

In the last few days, a new initiative:”9 euro fonds” has been started. The initiative started its work after the new government in Germany decided to cut off the 9 euro public transport tickets. The 9 euro funds are supposed to pay the fines of the people who have been penalized for riding public transport without a ticket.

The initiative is problematic for a few reasons: the most important is that most of the racialized, undocumented and/or migrants cannot afford to get a fine in the first place because it would impact their freedom, residency permits, or security. There are thousands of people in Germany who are in prison because of their inability to pay these fines.

Another initiative that fights against the criminalization of riding public transport without a ticket is Freiheitsfonds. The “Freedom Fund” initiative frees people who are in prison across Germany from using transportation without a ticket.

These initiatives, while far from perfect, give political agency back to civil society. Mobility shouldn’t be a luxury – it should be a right to be given to people independent of their financial ability and the 9 euro fund will not solve that. Nevertheless, it is an important step toward learning alternative ways for self-government.

Another good example is the solidarity fare share for sharing resources for the communities from the Neighbourhood anarchist collective. The Neighborhood Anarchist Collective (NAC) strives to grow the anarchist movement by taking action directly and locally by providing a welcoming environment for education and participation.

This is something we should learn from a lot of communities and organic movements around which their solidarity resource-sharing has always made them survive because sharing is not (only) caring, it’s political praxis.