As part of the governing coalition’s plans to reform immigration, the Ministry for Internal Affairs (Bundesministerium des Innern und für Heimat, BMI) headed by Nancy Faeser (SPD) published a draft of amendments to citizenship law on 23 August 23 2023. The BMI calls its plan a ‘modernisation of citizenship law’ with the purported intention of making Germany more attractive and welcoming to immigrants.

Presently, German citizenship law grants citizenship through five channels: birth (to at least one German parent), declaration, assumption in childhood, members of German minority groups abroad who re-settle in Germany, and naturalisation (Einbürgerung). The amendments to the current law mostly pertain to naturalisation—the process of assuming a new nationality as a foreign citizen, of which there are 11.6 million in Germany.

Under current law, citizenship by naturalisation is available to foreigners who have neither been convicted of nor are presently involved in prosecution for high-level criminal offences; have secured a place to live; and have achieved ‘integration into the German way of life’. They must also either have cohabitated with a German spouse for at least three years, or have lived in Germany for a minimum of 8 years, in that time posing no threat to public safety and order; present evidence of secure means to support themselves and any dependents without social assistance; give up prior citizenships; and demonstrate ‘sufficient knowledge’ of German language and civics.

Suggested amendments in the recently published draft include:

- waiving citizenship tests and scaling back language proficiency requirements for former Gastarbeiter

- automatic citizenship for children born in Germany provided at least one parent has lived in Germany for five years and has permanent residency

- a shortened minimum residency from eight years to five

- and, perhaps most eagerly anticipated of all, the right to dual citizenship.

Germany lags behind much of the world in its acceptance of multiple nationalities. According to Maastricht University’s Global Dual Citizenship Database, over 76% of nations have a positive policy toward plural citizenship. The database has documented a consistent increase in acceptance of multiple citizenship over the past several decades.

For many living in Germany, renouncing one’s original citizenship could pose an array of problems, such as endangering ease of contact with family and infringing upon a sense of personal identity.

While it is difficult to establish how many foreigners in Germany have abstained from naturalisation in favour of keeping their original citizenship, 5.3 million of them live in Germany long-term (i.e., at least ten years). One such individual is Berlin-based software tester Tekin. Despite a light but distinctly German Franconian accent, Tekin is a Turkish citizen.

‘I was born here, I went to school here, everything—despite that, I can’t vote. As soon as having a second passport is allowed, I’ll apply for it.’ Tekin has found the rise of the extreme right in Germany particularly distressing and is planning a two-month trip to Turkey to cope. ‘I feel so uneasy in Germany now. Every third person seems to be voting for the AfD and is therefore an incognito Nazi.’ An unwelcoming homeland and powerlessness to enact change democratically highlight the importance of both citizenships for Tekin.

Statista records Turkish nationals as the largest non-German minority in the nation at 1.5 million. If all 85 million people living in Germany had the right to vote, they would make up 1.8% of the voting population, with foreigners overall making up 14%.

Data on foreign nationals’ forecasted party alignment is scarce. However, a 2021 study in Duisburg found that German citizens with a Turkish background (either naturalised citizens or with at least one Turkish parent) were most likely to vote SPD (4% more so than those with no personal or familial immigration background). Participants also reported an incidence of voting for the Linke four times higher than that of those with no immigration background and a low incidence of voting for the AfD.

It remains to be seen how expedited naturalisation will be reflected in the German political landscape, but the represented parties shared their positions on the drafted amendments upon proposal this past May. From within the ruling coalition, the Green party hopes that the changes will make Germany a ‘more attractive’ immigration hub. The SPD placed emphasis on the need for double citizenship, while the FDP primarily cited the ostensible workforce crisis as a motivation for easing the path to citizenship.

The Linke notes that while immigration in Germany rises, naturalisation rates have stagnated. The party positions itself against exclusion from citizenship based on socioeconomic status, language skills, and civics tests, and stands behind implementing a right to dual citizenship.

To their point, applicants would not necessarily be denied citizenship for rightfully receiving social assistance. In addition, among the new amendments is the further reduction of the residency period from 5 to 3 years for ‘special integration efforts’ among which are listed excellent school achievement, C1 language knowledge, and volunteer efforts. Applicants are meant to meet conditions that are not imposed on ordinary Germans.

The BMI defines ‘integration’ as ‘a process with the goal of including all who live in Germany long term and legally in society…Immigrants have the obligation to learn the German language, to know, respect and follow the constitution and the law.’ It further states that integration gives immigrants the same chances and access to civil participation as native citizens.

The emphasis on ‘integration’ extends to the implementation of an Einbürgerungsfeier (citizenship ceremony). The Einbürgerungsfeier is one of several elements to the BMI’s new immigration package drawn from Canadian citizenship law. Canadian immigration policy awards points largely based on qualifications and existing job offers within Canada, but also deducts points for other factors such as age [1]. After five years, immigrants are permitted to apply for citizenship. The citizenship ceremony in Canada is a symbolic event at which successful applicants take an oath declaring their new citizenship.

Canada is far from a multicultural paradise, as was laid bare in past years when atrocities of residential schools were exposed to the world, and when right-wing demonstrations took hold during the pandemic. Yet, it does have some cultural advantages where Germany has deficits which may have been lost in translation during the BMI’s consultation on Canadian immigration policy, and which will be difficult to remedy with a state-mandated party.

95% of Canadians are non-indigenous and thus have a history of immigration. Canada is sometimes described as a cultural ‘mosaic’ to differentiate it from the US ‘melting pot’. If the US-American historical approach to immigration and naturalisation has been ‘anyone can become American’, Canada’s is ‘many different people are Canadian’. The elementary school curriculum in Ontario, Canada’s most populated province, prescribes the acknowledgement of Canada as a nation of immigrants and encourages students’ discussion of their own heritage and immigration history, where applicable. Global citizenry is introduced as a concept as early as age six, with asylum-seeking and immigration the following year. Cultural coexistence is not only an academic affair; an estimated 4.6 million Canadians speak a non-official language at home and around half of residents in Toronto, the nation’s largest city, are immigrants. Equivalent information is difficult to find in Germany, partly because of restrictive policies on data collection regarding race and cultural background.

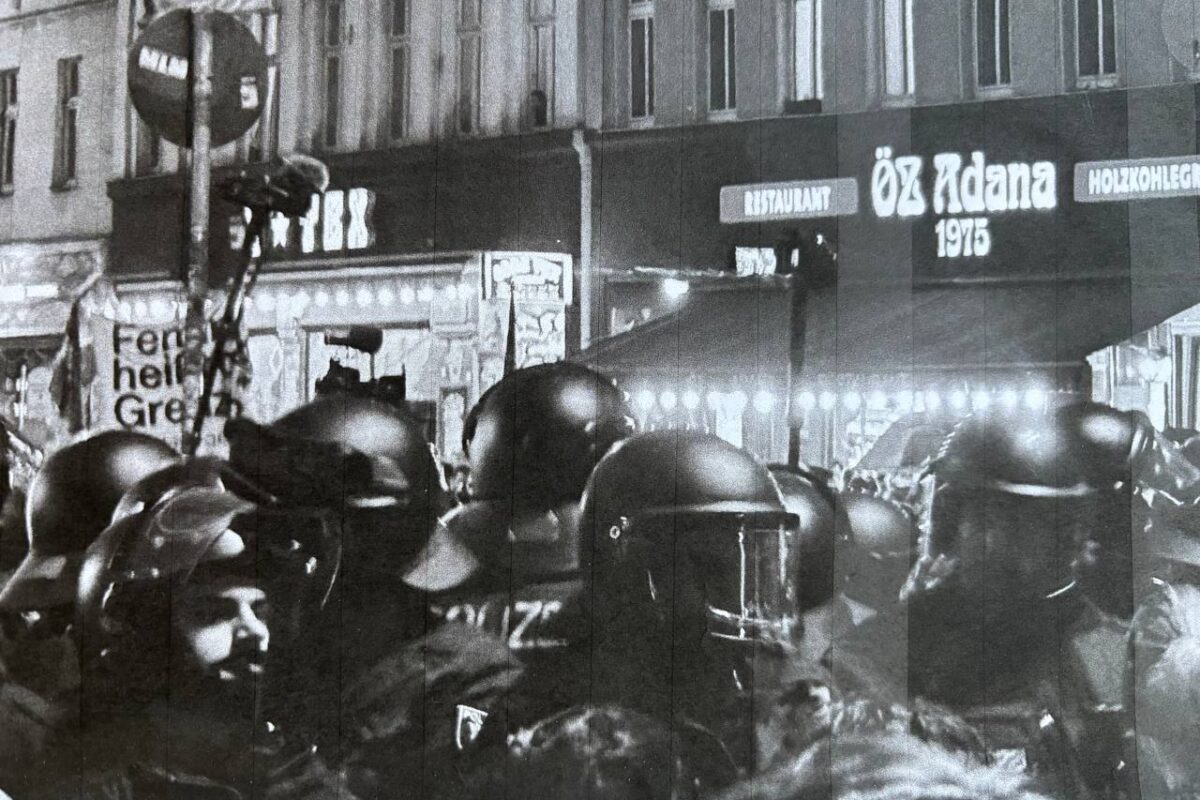

Moreover, the recent quashing of demonstrations in support of Palestine call into question Germany’s preparedness as a society to welcome diversity. It raises concerns surrounding what actions could be seen as ‘failed integration’. Middle East Eye reported an estimate of up to 100,000 Palestinians and descendants in Germany with 25,000 in Berlin alone, making it home to one of the largest Palestinian diaspora outside the Middle East. Despite Palestinian families making up a significant minority in Germany, recent events have illuminated legislative and social rigidity regarding cultural acceptance. The keffiyeh, a scarf culturally significant to Palestinians, is banned in Berlin schools. In another incident, a dispute over a student bringing a Palestinian flag to school resulted in a teacher punching a 15-year-old student in the face.

A shortened wait before becoming a citizen and a positive policy move toward dual citizenship are encouraging and necessary changes. Nonetheless, as Berlin internationals watch increasingly unbridled oppression of free speech unfold in the streets, they may be forced to wonder if their resistance could prove burdensome on their pathway to citizenship. All the while, Faeser crams a mosaic of traffic onto a one-lane assimilation street—without the infrastructure to support Germany in integrating into a multicultural society, the nation is unlikely to become more welcoming and ‘attractive’ to non-German citizens through policy alone.

The draft is now in the Bundestag, where changes can be suggested. Official dates for the law to come into effect have yet to be announced, but the BMI projects it will be finished ‘in the first six months of 2024’.

Tekin eagerly awaits becoming a citizen of the country they call home, voicing frustration with their exclusion from politics. ‘It doesn’t matter what I achieve here, as long as I’m not German on paper, I can’t partake in decision-making. My future is in the hands of others. And it’s not looking good.’ Even in the best of cases, they have reservations about the social impact—or lack thereof—that a German passport will bring.

‘Germany doesn’t give me a feeling of belonging…even when I’m ‘‘officially’’ German, I’ll still be a foreigner to others, despite being born and raised here. And in Turkey, I’m an Almanci. I’m not a German in Germany, I’m not a Turk in Turkey—I’m Tekin.’

Footnotes

- I, a Canadian citizen, scored 341 out of a possible 1200 points; 110 were due to being 28 years old.