27th July 1919 was a hot Sunday. To escape the heat, many Chicago residents went swimming in Lake Michigan. One group of Black teenagers floated on a raft towards waters the White residents had designated “White only”. A White man on the shore, George Stauber, threw rocks at the raft. One hit 17-year-old Eugene Williams on the head and knocked him into the lake. He drowned. A White policeman who witnessed the event refused to arrest Stauber. Instead, he arrested a Black man for a separate offense.

Public murders of Black men were common in the USA: in 1918, in the Southern states, the Ku Klux Klan lynched 64 people. By 1919, this figure had risen to 83. But this was not just a Southern phenomenon. Other forms of discrimination were also deliberately used. In 1917, Chicago state housing introduced racial segregation. Meatpacking industry bosses underpaid Black workers and used them as scabs to break strikes.

Until now, Black Americans had been expected to accept discrimination and murder. But many Black men had fought in World War I “to preserve democracy” and were no longer willing to tolerate injustice. Black socialist and activist W.E.B. Du Bois called on Black veterans not simply to “return from fighting” but to “return fighting”. Similarly, a Black trade union member in Chicago said, “All we demand is the open door. You give us that, and we won’t ask nothin’ more of you.”

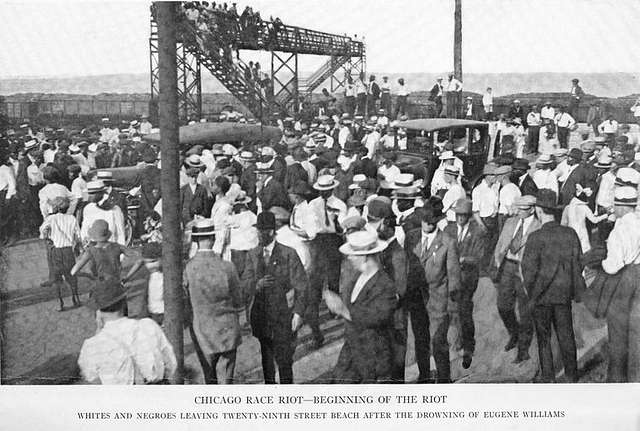

1,000 Black residents assembled at the scene of the killing to call for justice and for Sauber’s arrest. The riots that followed lasted eight days. Twenty-three Black people were killed, as were fifteen White people. 537 people were injured, two-thirds of them Black. Between 1,000 and 2,000 residents, most of them Black, lost their homes, mainly due to arson. No one was convicted of Williams’s murder – and two-thirds of convictions were of Black men. Many White rioters who were arrested were immediately released by the police.

The immediate impact of the Chicago Race Riots was defeat and division. But it showed a new Black militancy, together with a willingness among some White Chicagoans to support their Black brothers and sisters in the fight. It showed that resistance to racism was possible. If you are interested in knowing more about the causes of the riots, and the hope of united resistance which followed, I would recommend the film The Killing Floor, produced by Berlin-based activist Elsa Rassbach.