Memory on trial: the Berlin case

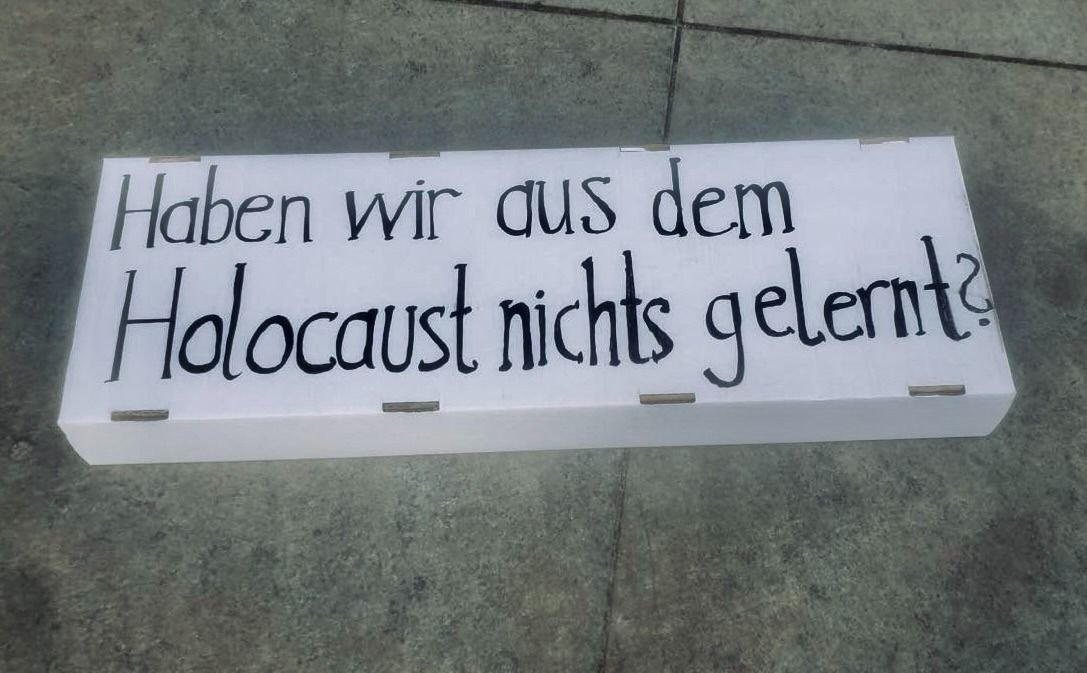

On April 24, this year, a Berlin Court sentenced an activist for incitement to hatred after she walked around the Bundestag on November 3, 2023 with two signs reading “No to the murder of 8.500 civilians in Gaza so far” and “Have we learned nothing from the Holocaust?” The ruling made clear that in Germany, drawing any connections between the Nazi Holocaust and other atrocities is not tolerated.

Trial and ruling

The activist was convicted of Volksverhetzung, under Section 130, par. 3 of the German Criminal Act, according to which anyone, who publicly or in a meeting, approves of, denies, or downplays crimes committed under National Socialism, as defined in Section 6(1) of the Code of Crimes against International Law, in a way that could disturb public peace, may face up to five years in prison or a fine.

The prosecutor accused the activist that, by carrying the two signs, she had equated “the fate of approximately six million Jews and other persecuted groups who were industrially deported and exterminated under Nazi rule” with “Israel’s and the IDF’s response to the terrorist attack of October 7, 2023, to the detriment of approximately 8,500 civilians in Gaza.” The prosecutor further stated that by doing so, the activist had “trivialized the nature, scale, and consequences of the oppression, violence, and mass industrial extermination (…) due to the obvious imbalance between the events.”

The activist claimed that her reference to the Nazi Holocaust was meant as a moral warning motivated by Germany‘s pledge of “Never again”, which she understood as a commitment to oppose all genocides, regardless of where and against whom they occur.

Her lawyer supported her claim by describing the ongoing mass atrocities unfolding in Gaza and citing both international law and the testimonies of Holocaust survivors who spoke of the responsibility of “Never again” precisely in light of the situation in Gaza. Therefore, the lawyer argued, the defendant’s action should be considered as a political expression protected under the right to freedom of expression. The lawyer also referenced established jurisprudence of the Federal Constitutional Court, which holds that where a statement can be understood in several ways, courts are obliged to consider the least punishable interpretation to protect freedom of expression.

The Berlin District Court, however, followed the prosecution and found that the combination of the two signs constituted a direct comparison between the Nazi genocide of six million Jews and other victims and “Israel’s military response to the October 7, 2023 attacks”, and that the disparity in nature, scale and consequences between the two events amounted to a clear trivialization of the Nazi crimes by violating the dignity of their victims. The Court further noted that even under the protection of freedom of expression, there was no other more favorable interpretation conceivable.

Courts under scrutiny for trivializing genocide

The Court’s ruling was heavily criticized by scholars and activists alike because it seemed less about sound legal reasoning and more a part of a broader trend in German jurisprudence shaped by German Staatsräson—the state‘s commitment to Israel’s security as a reason of state.

The claim that the activist downplayed the Nazi Holocaust appears implausible indeed, as her action precisely raised the question of what lessons have been learned from the Holocaust—particularly in the face of another ongoing genocide that, at the time of her protest, numerous human rights organizations and renowned genocide scholars like Raz Segal, had already described as a textbook case of genocide.

Furthermore, the International Court of Justice has affirmed that genocide is not established by the number of victims but primarily by a genocidal intent. Against this background, it is difficult to understand why the Court based its assessment largely on the disparity of victim numbers—especially considering that the activist herself did not equate these figures. Instead, the Court should have considered that Israeli officials with command authority have been openly using dehumanizing rhetoric that refers to Palestinians as “human animals” and Gaza as “the city of evil”, and have explicitly expressed genocidal intent by declaring their aims such as “razing Gaza” and “we must erase the memory of Amalek”.

It would also have been relevant for the Court to take into account the situation in Gaza at the time of its ruling, in order to assess the foreseeability of the scale of these events. By then, more than 51,000 Palestinians had reportedly been killed—bombed, deliberately shot or starved to death. Tens of thousands were missing. Almost the entire population had been displaced and 92% of all housing units destroyed or damaged. More than two thirds of Gaza’s educational, religious, cultural and health care infrastructure had been completely destroyed, including universities, schools, mosques and cultural sites. Nearly all hospitals were targeted. Hundreds of teachers, writers, artists, scholars,journalists and health workers were arrested, tortured or killed. Since March this year, the remaining population, already subjected to a complete siege, has been facing a total blockade on humanitarian aid, which many observers have described as a deliberate campaign of mass starvation, with Israeli distribution centers turning into deadly traps.

In light of these considerations, one must seriously question whether it was the activist who trivialized the Nazi Holocaust, or rather the Court itself—by instrumentalizing the legacy of the Holocaust to downplay the magnitude of another ongoing genocide, now entering its 21st month, and thereby desecrating the very legacy it claims to protect.

Holocaust and the struggle over language

The Berlin case raises broader questions about Germany’s claimed singularity of the Nazi Holocaust, how the genocidal events are interlinked, and more fundamentally, what language we use to speak of today’s atrocities and of the genocide in Gaza.

Singularity and interconnections of genocides

There is a German obsession in general to treat the Nazi Holocaust as an unique and untouchable event—something that has fiercely been defended, notably during the Historikerstreit of the 1980s. This is understandable to the extent that every genocide unfolds in its own specific historical, political and social context.

The Nazi Holocaust stands out as the first large scale genocide of more than 6 million European Jews and hundred of thousands Roma and Sinti, disabled people, and political dissidents, executed with chilling bureaucratic efficiency, by a modern European fascist state, on European soil, and with extensive documentation through survivor testimonies and institutional archives. It was also the genocide that helped lay the foundation for the modern international legal system, including the drafting of the Genocide Convention.

What is happening in Gaza is historically unprecedented too. It has become the first genocidal campaign to be livestreamed in real time with daily footage documenting the systematic mass killings and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, and the deliberate destruction of their land. It is also for the first time that a world court has ruled a state plausibly committing genocide while atrocities are still ongoing. A historical irony lies in the fact that the mass killings are being carried out by a state, itself partly founded by survivors of the very genocide that led to the modern international framework. A framework that is now collapsing in front of our eyes in Gaza.

It is important to comprehend these genocidal events in their broader contexts as the histories of Germany, Israel and Palestinians are deeply intertwined. Germany, once the perpetrator of the Nazi Holocaust, today supports, both politically and through arm sales, descendants of its victims in carrying out another genocide against another people. It does so, cynically, under its Holocaust banner of “Never Again”.

These events are not isolated from all other atrocities either. They have to be viewed within the longer legacies of Western colonialism. This includes racialized state violence and the systematic dehumanization of marginalized groups labeled by dominant state powers as “the other”—as was done with the European Jews and Roma and Sinti under Nazi Germany, with the Tutsis in Rwanda, and as is happening with Palestinians under Israeli occupation today.

To relate and also compare such genocidal events is not the same as equating them. In fact, it is a necessary effort to be made—to understand their causes, patterns and consequences, in order to learn from them, prevent their repetition, and hold the perpetrators accountable. When those who draw these connections are systematically silenced, then the activist’s question—”what have we learnt from the Holocaust?”—becomes not only justified, but essential.

Language of atrocities, and who owns the word “Holocaust“

What has been unfolding in Gaza today goes further than many atrocities we have previously witnessed. The sheer scale and horrific nature of this genocide have long surpassed a threshold that demands a serious and urgent reconsideration of the vocabulary available to describe atrocities of such magnitude, including whether the term holocaust, in its broader historical and linguistic sense, may be rightfully invoked in this context.

First, it is important to note that the word holocaust is not a legal term. In contrast, the word genocide is legally defined in the Genocide Convention of 1948 and means the intentional destruction, in whole or in part, of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term genocide in 1944, had envisaged it to entail not only the physical destruction of a population but also the destruction of its culture, language, and identity. His broader vision was, however, excluded from the final text of the Genocide Convention.

The word holocaust, meanwhile, predates World War II and—contrary to common belief—was not originally coined to describe the Nazi genocide of the Jews. The term derives from the Greek word holokaustos which means burnt (kaustos) as a whole (holos) and was historically used in religious contexts for a burnt sacrifice. Later on, it was applied more broadly to describe mass atrocities, particularly those involving fire and destruction, including the genocide of the American natives, the Armenian genocide and the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima.

While in Hebrew discourse, the term shoah—meaning catastrophe—has long been the standard reference to the Nazi genocide when written with a capital S, in German discourse, holocaust entered common usage only after the 1979 broadcast of the U.S. television miniseries, Holocaust: The Story of the Weiss Family. Until then, postwar German discourse used words like genocide or mass murder to describe the Nazi crimes against the Jews. 1979, the year when the miniseries was broadcasted, holocaust was voted by the German Language Society as “Word of the Year“, marking its entry into German common language and as a synonym for the Nazi crimes, when written with a capital H.

Some genocide scholars, who have applied the term holocaust to other cases have proposed different moral and historical frameworks to define such events. While no fixed criteria exist, most frameworks include large—scale killings of civilian populations based on their identity (e.g. ethnicity or religion) and motivated by state ideology, destruction of their cultural infrastructure and memory, and irreversible demographic, psychological and cultural loss.

Based on this understanding, it is suggested to distinguish between the term genocide as a legal definition of mass atrocities emphasizing intent, and holocaust as an extension beyond legal criteria that captures the historical and moral dimensions of such atrocities. The word holocaust would thus include not only the intended physical erasure of a people but also—as Lemkin had once advocated for—the erasure of their identity, culture and collective memory, with a moral and historical long lasting impact.

Applying these criteria to the case of Gaza, it is striking with which clarity they are met, considering the available evidence, including footage, eyewitness accounts and detailed reports of international and local organisations.

For almost 21 months, Palestinians have faced systemic large-scale mass killings, with entire neighborhoods erased and families exterminated. We have been watching children, journalists and injured civilians in flames, burning alive in shelters meant to protect them. Children have been deliberately shot in the head, and women specifically targeted, in an effort to halt the continuity of Palestinian life. Gaza’s infrastructure has been largely completely destroyed, its landscape flattened and made unlivable. This comprehensive destruction of life, homes, cities, culture, knowledge and environment have been accompanied by a genocidal rhetoric from Israeli officials expressing a clear ideological intent to erase not only Palestinian life but also its memory and future.

Gaza cannot be seen merely as an international political crisis or a humanitarian catastrophe. Rather, it marks a rupture, revealing a profound moral failure of our modern international legal order and of self-proclaimed liberal democracies whose support has enabled this genocide to unfold in the first place.

To reserve the word holocaust solely for one historical event seems not only presumptuous, it also restricts the vocabulary we need to grasp, articulate and respond to atrocities of such magnitude. Ultimately, to have the language to thoughtfully express what the atrocities in Gaza represent is not a matter of rhetorical provocation, but one of moral and historical responsibility.