After decades of virulent polemics, is the tide turning on identity politics? Looking at the Pluto Press catalogue, it would seem that there is hope for that. In May, Pluto was the European publisher of Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s hit book Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else). Pluto’s September releases include a new book that cuts identity politics some slack. Fractured: Race, Class, Gender and the Hatred of Identity Politics provides an earnest exploration of identity’s political importance, supported with thorough historical evidence and a willingness to answer flippant anti-wokeness with theoretical arguments.

Fractured is authored by Michael Richmond and Alex Charnley, co-editors of Occupied Times and its successor magazine, Base. The two want to go beyond the use of “identity politics” as a “political smear,” using it instead as an entry point into a diagnosis of the UK and US left. Refusing to accept the premise that identity politics is divisive in itself, Richmond and Charnley set off to analyze the fractures that structure societies and social movements along the lines of race, class, and gender. Identity politics does play a role in that, but against a class-reductionist common sense, Richmond and Charnley argue that it bridges more than it divides. What sets Fractured apart from the hundreds of publications on identity politics that come out every year is a commitment to take it seriously as a source of radical solidarity, in the past as well as today.

This means that Fractured is not about a vague, amorphous zeitgeist that could refer to anything from the “trans ideology” to tearing down slaveowners’ statues, depending on the target of one’s ire. Although such subjects are discussed throughout the book, the core of the argument is a close analysis of the source of identity politics: Black feminism. Chapters two and three of the book detail the development of this radical tradition in the US and the UK, respectively. The term “identity politics” itself was first coined in the 1977 “Black Feminist Statement,” authored by the Combahee River Collective. What the Collective theorized and supported was Black feminism as an autonomous tradition challenging the whiteness of feminism and of socialism, and the maleness of Black nationalism. For Richmond and Charnley, this separates identity politics from fixed “identity-thinking” from the start. Radical politics, for Black feminists, did not mean affirming individualized categories, but challenging them.

Identity politics is an attempt to confront exclusions and fractures, to trouble immutable categories, and to create an “identity of purpose,” a term that Richmond and Charnley borrow from Ruth Wilson Gilmore. In the UK, Black and Asian feminists were developing their own radical critique at the same time as the Combahee River Collective. As this took place during rapid changes in the nature of global capitalism, the book emphasizes that identity politics is not the abandonment of class politics that it is usually painted to be. On the contrary, the “Black Feminist Statement” was written in direct dialogue with socialism and Marxism. British Black feminists such as Hazel Carby were also responding to the changing class composition of Britain in the 1970s, when Black and Asian women were restructuring labor, but unions were lagging behind in their organizing strategies.

It is this idea that identity politics can help us understand and deal with class composition that drives Fractured. The other chapters in the book spell out its importance. We need a politics of identity because capitalist society is not reducible to relations of production and a homogeneous waged working class. Racism and sexism are real forces that fracture and divide people’s personal and political existences. Unfree labor, unrecognized reproductive labor, as well as direct violence along racial and gender lines have marked the development of capitalism as much as industrial exploitation. Chapter one brings this reality to the fore by detailing the importance of racialized enslavement to the British Empire and the United States. It also centers, however, Black agency in fighting against slavery and for its abolition, and the importance of this long history to antiracist movements today.

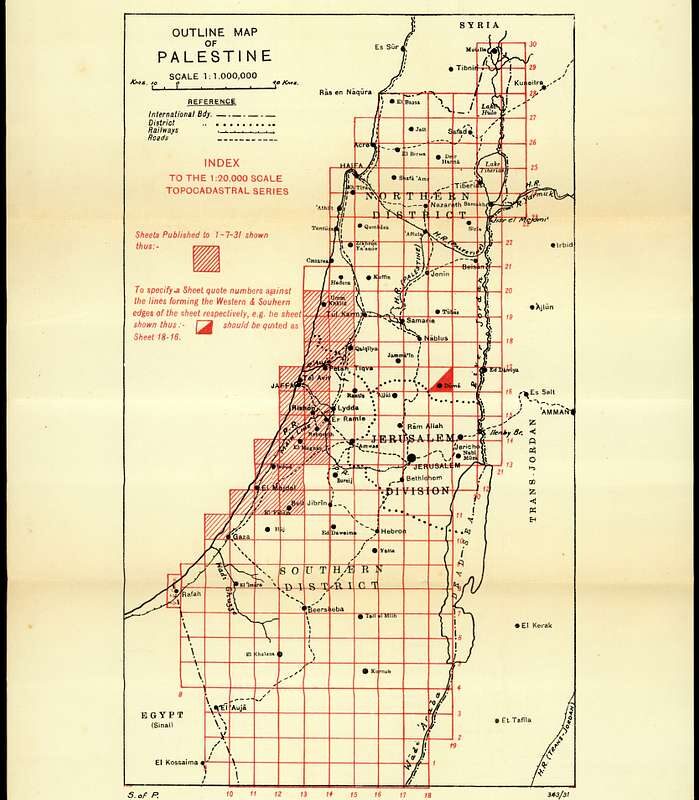

Chapters four and five turn their attention to borders and to the nationalism of early labor movements. If British socialists at the turn of the 19th century defined themselves against Eastern European Jewish immigrants, American workers at the same time were also organizing against, not together with, precarious Chinese laborers. Chapters six and seven focus on 1919, a year of “race riots” in both the US and the UK. The authors again show that labor was more often on the side of the aggressors than on that of the attacked. All this is peppered with references to contemporary examples of anti-identity politics, from racist reactions to Black Lives Matter protests, to Britain’s new Police Act, to trans-exclusionary “feminism.” In these histories, Richmond and Charnley seek and find examples of alliances and solidarities built through the labor of organizers and activists. But the fact that these solidarities take work and effort supports the larger point: showing that divisions are real, not superficial impositions on the working class by scheming capitalists. As such, leftist politics must work with them through identity politics, and not simply dismiss their existence.

The theoretical and historiographical breadth of the evidence that Richmond and Charnley bring in support of this argument is impressive. But while it is necessary that any serious discussion of identity politics relies on such concrete examples, the scope of the book also burdens what could have been a much more streamlined argument. Take chapter three, for instance. The discussion of British Black feminism is interrupted by a six-page detour into the complexities of labor and suffragism almost a century earlier. The point that “Black and Asian feminist critiques of ‘white feminism’ in the 1970s can be understood as a revision of earlier critiques of imperialist suffragism” is well taken. But the chapter already draws out debates about gender, race and class, Marxist historiography, carceral feminism, patriarchy and reproductive work, sectarianism, and a few other concerns. I cannot help but wonder whether this historical excursion added anything to the point being made. Indeed, in the theoretical and historical thicket, it is sometimes easy to lose track of that point.

The same is true for the whole book, as the authors slalom through the turn of the 19th century, the 1970s, and the present day in the US and the UK. While these contextualizations are needed to nuance polemics about identity politics, expecting just one book to cover all this ground is an ambitious task. This is perhaps due to the wide scope of the “hatred of identity politics.” Richmond and Charnley rally against all forms of antiwokeness, be they from aggrieved white reactionaries, colorblind liberals, or class-reductionist leftists. That ostensible socialists, conservatives, and white supremacists end up propagating the same anti-diversity talking points is something that we have not reckoned with enough. Confronting all of them in just one book, however, comes at the expense of a clearer target.

Richmond and Charnley write, for instance, that Tory appeals to the “white working class” and the class-reductionist left are predicated on “the same oppositions between ‘identity politics’ and class.” But do Vivek Chibber and the Conservative Party really share an analytical basis? And, more importantly, can they both be addressed in the same way? Criticizing racist labor movements and showing that identity politics is a generative response to changing class compositions might be proper arguments for economistic leftists. But the same strategy does little against those who premise their hatred on the belief that change in class composition itself is the problem and that nationalism is the natural answer.

Nevertheless, Fractured’s merit is to have found a common thread throughout these different hatreds, one that clarifies and contributes to progressive debates. Anti-wokeness, on the left, center, and right, deals in false and exclusionary universals. It papers over real differences within liberal societies and within the working class. Reactionaries might embrace such exclusions, but for leftists this should be a wake-up call. The takeaway is that “calls for the ‘unities’ of unspecified pasts, contrasted against today’s betrayals of class universalism” are not only empirically dubious, but also actively harmful. Categories such as “working class” or “womanhood” have never been pure universals. They are fractures solidified as reactions to capitalist violence and division – fractures that identity politics, despite the reputation it has gained, wants to overcome.

Richmond and Charnley refuse to simply continue the polemics in their book, and bring in histories, examples, and theories. They show that Black feminism and identity politics have already been fighting to defeat empty, nostalgic categories, and that we all need to learn from them. As overwhelming as Fractured’s historiographical trajectories may be, they make an impact as examples of “revolutionary times” and “experiments in radical universality.” This impressive book brings badly needed concreteness to debates that too often consist of sweeping generalizations. In doing this, it points toward radical possibilities in the here and now. Because, even though Richmond and Charnley tell histories of racist violence, hardened borders, and exclusionary identity categories, they do not wallow in defeats. Rather, they want us all to learn the lesson that Black feminism teaches: “We have only this world, a wrong world, with which to work.”

Fractured is available from the Pluto Press website.