When I was 6 years old, my friend invited me to his birthday party. I solemnly carried the cake with candles into the room. Someone turned off the lights. I fell. It was funny.

On my 31st birthday, I seriously wanted to go to Auschwitz. I settled just 33 kilometers away from it – in a Polish mining town that was the complete opposite of my hometown.

Everything in this town reminded me of Auschwitz. I didn’t end up there on my birthday, but much later, on the last day of my stay in that region, after I had finished working on the first draft of THE MINING BOYS.

When I left my home on the day the war began, I took a few books with me. One of them was a concentration camp guard’s diary. I bought this book along with a book about Ancient Rome Empire to understand history and figure out if there would really be a war between Russia and Ukraine. But as usual, I approached the matter too pragmatically. I could have skipped Rome and focused on the last 3 decades instead.

And yet, when I was hiding in western Ukraine from the war, only the diary of a guard from a concentration camp remained with me. The diary stayed with me because it an English translation. The other books were in Russian, and I had to throw them away to save myself. Since childhood I’ve been wary of people who mistreat books. And now my own hand tossed two brand-new books into the trash with leftover hot dog wrappers, used tea bags, and hopes for the end of the military conflict.

I visited Auschwitz with a friend. They gave us headphones, and for about 3 hours, we were led around the vast territory of fear. I expected to be terrified, but there was no terror. I prepared myself to feel disgust towards all humanity after the trip to Auschwitz, but I didn’t feel anything like that. Numbness. Yeah, numbness! That’s what it was. Just like in the Pink Floyd song ‘Comfortably Numb.’

During the 9 months I spent in Ukraine during the war, I saw how people willingly embraced sudden power. I witnessed crowds eager to submit to authority in under high stress. I heard kids expressing hatred towards men because their dads had already died, yet for some reason these so-called men were still alive. So where is the justice?

After these 9 months, Auschwitz didn’t scare me, but it turned out to be a logical continuation of mass hatred. Hatred has no nationality, no rational reasons. Hatred is an emotion that people often delegate control over to someone else.

When the guide led us to the crematorium and began to explain how it functioned, I could easily imagine the kind guard from the Lviv office where I lived for 2.5 months, innocently pushing bodies into the oven while shrugging his shoulders. It’s an order. The responsibility for the order lies not with the one who carries it out, but with the one who gives it. And then the friendly subway attendant came to collect shoes. Hello, Maria, what time do you finish today?

My friend and I saw salvation from inhuman hatred in Western culture. Whether American or European, Western culture puts the person at the forefront, not the state apparatus. Even if this person has his pants down.

Because we both saw salvation in culture, my friend constantly tried to distract himself from the unpleasant stories of the guide by looking at paintings. They show us the crematorium ovens, and my friend stares at his phone. They lead us to the wall where executions took place, and my friend is again glued to his phone.

I ask, “What are you looking at?”

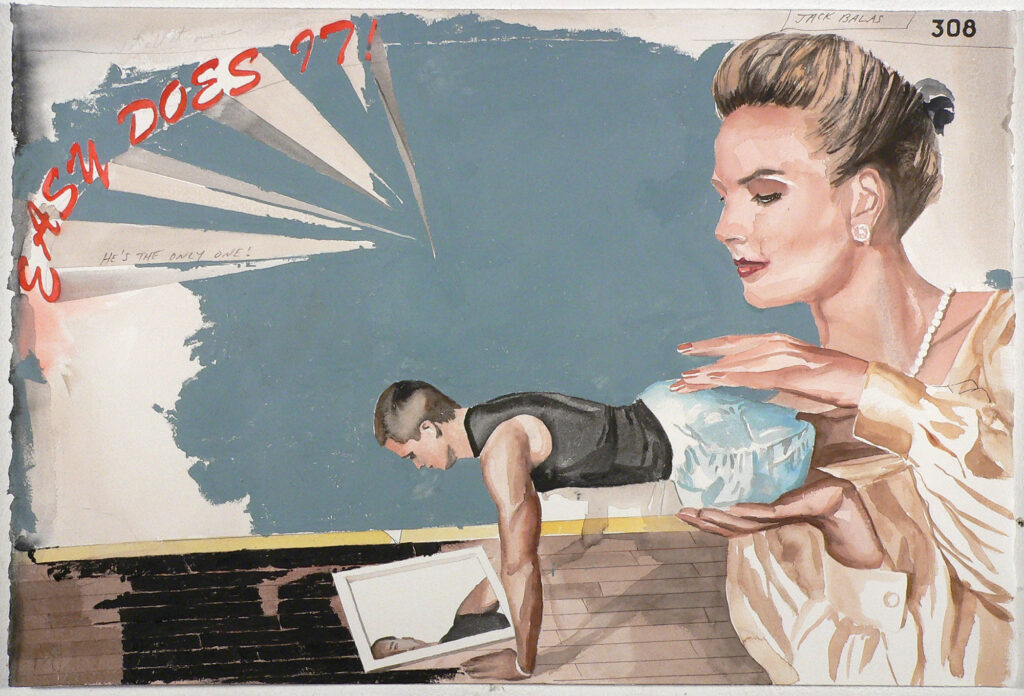

He smiles and shows me brilliant works by an American artist.

“This is Jack Balas.” My friend says his name with such a facial expression as though it vibrated on his tongue, bringing physical pleasure.

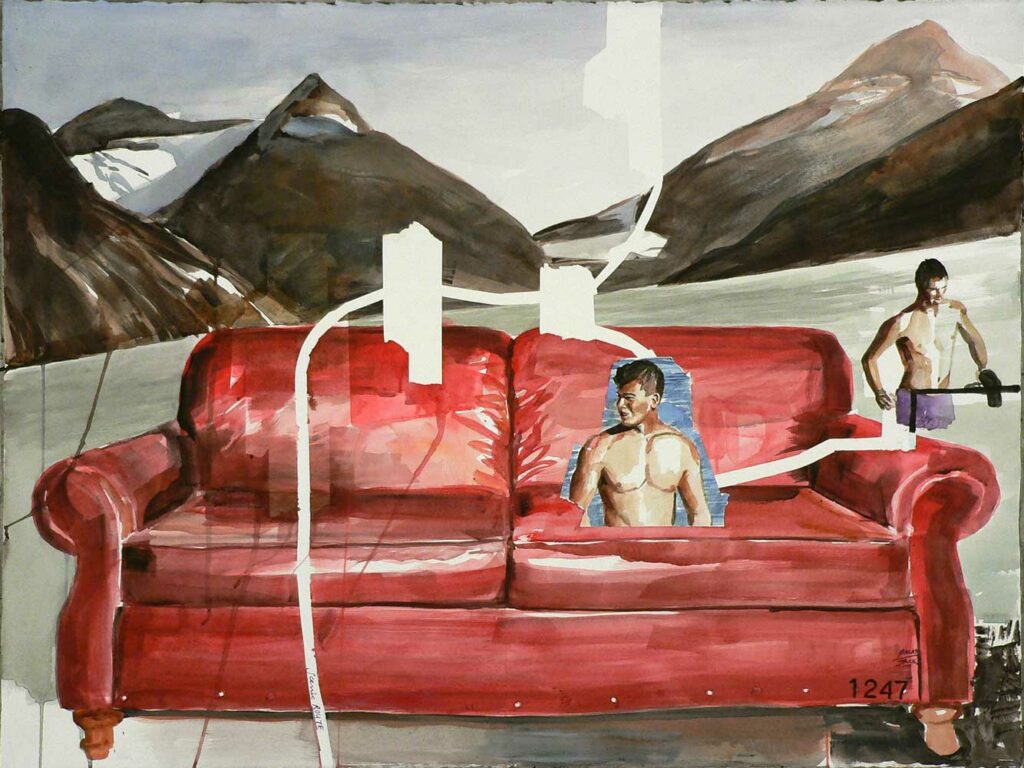

Jack Balas. Ridiculous as a couch against the backdrop of mountains. Quirky as a fish stuck in a basketball hoop. Jack Balas. A contemporary artist. It’s so hard to get excited about contemporary artists. And so, I came across his work in such an unexpected place – within the walls of a concentration camp.

Perhaps I managed to discern Jack Balas’ talent precisely because of Auschwitz. Beautiful paintings become even more beautiful in a horrific place. Contrast. Pumped-up guys. Healthy bodies, demonstrating with all their might a thirst for life. And suddenly, our guide pulls out a tablet and shows us pictures of emaciated bodies of concentration camp prisoners.

In one of Jack Balas’ paintings, a man hugs a snow-covered mountain. I was that mountain. It was important for me to have someone hug me.

My phone vibrates. Unknown number. I answer. I hear Ukrainian. There are almost no people around me who speak Ukrainian. And certainly, none who could call me using Ukrainian. This stranger turned out to be a representative of the Ukrainian military enlistment office. He introduced himself and asked if I wanted to come in to update my information in their registry. I didn’t want to. I hung up.

Just a second ago I was a mountain, and now I’m 6 again and someone has turned off the lights.

I wanted to throw away my phone. Drown it in the sewer, let the sewage carry it away farther than I could reach on foot.

The military officer called me in Auschwitz! Damn it. Damn! In Poland. I thought they couldn’t reach me anymore, but the enemy is nearby – in my pocket, in my phone. Touching my soft ear with its unwelcome voice. Boldly touching. Nah… I won’t give you my life, sir. One evil extended its hand to another evil, merging in a handshake in my ear canal. I won’t contribute to the war in any form. Just as people in stressful situations seek salvation in the orders of a tyrant, I sought salvation in culture, wanting to cling to a human with his pants down.

My friend asks who called, then immediately shows me another painting by Jack Balas. A mountain gets better when another mountain hugs it. Especially if it’s a warm mountain of muscles.

This piece is a part of a series, The Mining Boy Notes, published on Mondays and authored by Ilya Kharkow, a writer from Ukraine. For more information about Ilya Kharkow, see his website. You can support his work by buying him a coffee.