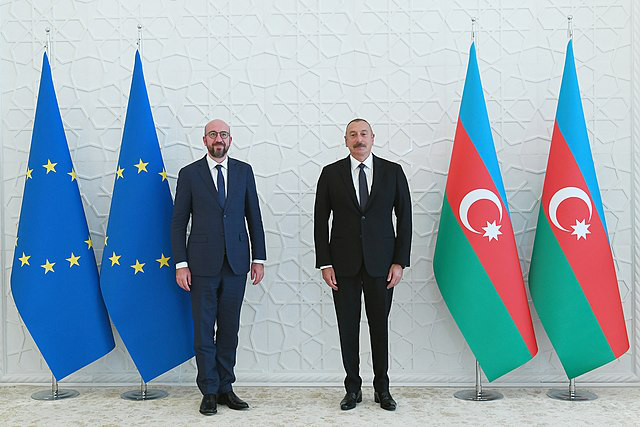

A party which has monopolized power for decades, a muzzled press, an army that regularly violates international law and commits war crimes, and a mafia clan that holds on to power thanks to its gas exports… You might think we’re talking about Vladimir Putin’s Russia, but we’re actually talking about Ilham Aliyev’s Azerbaijan. Far from being considered a rogue state by the European Union, the latter has steadily drawn closer to Azerbaijan since the start of the war in Ukraine. Ursula von der Leyen described Ilham Aliyev as a “reliable and dependable partner” at a press conference in July 2022, only shortly after the Azeri regime re-started its campaign of brutal military aggression against its Armenian neighbor. Could the European Union once again offer up Armenia as a sacrifice to the appetites of Azerbaijan?

The 44-day war between Armenia and Azerbaijan in 2020 did not draw special attention from Western journalists. Yet the intensity, brutality, and innovative military strategies of this invasion were anything but commonplace in the Caucasus region. The total war waged by the Aliyev clan’s regime took up old practices such as the bombing of civilian targets, extreme anti-Armenian hate campaigns, execution of prisoners, torture of civilians, and psychological warfare aimed at paralyzing the opposing side, among other tactics.

The conflict also took on the hallmarks of the 21st century. The use of drones became a central element of Azeri tactics, due to their noise – which sows panic among civilians and soldiers alike – and the difficulty in tracing them. Images of the torturing of civilians and prisoners were shared on Azeri Telegram feeds, showing soldiers laughing. At the same time, Azerbaijan’s army chief and president celebrated their victories by listing the capture of villages and towns, one by one, on Aliev’s Twitter account. The psychological effect on Armenians was significant – all in a context where no one contested the Azeri triumph.

Only a month after the war ended in November 2020, Ursula von der Leyen’s administration, through Josep Borrell (High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy), declared that “the EU wishes to conclude an ambitious new comprehensive agreement with Azerbaijan, based on democracy, human rights and fundamental freedoms” after a meeting with Azeri representatives.

Azerbaijan’s recent victory was built on the pillars that Aliyev’s father built after a military defeat in 1994, when the Armenian army penetrated Azeri territory to secure the borders of the newly self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh. The head of state used the military defeat and the hundreds of thousands of internal refugees to reinforce Armenophobia. Armenophobia has long been alive and well in the region – one need only recall the Armenian genocide for proof of that.

Reopening old scars

During the first years of independence in the 1920s, various massacres took place between the two ethnic groups before the formation of the Soviet Socialist Republics. As a result of these events, the Nagorno-Karabakh Oblast was founded as a quasi-independent territory in 1923.

Stalin decided that the territory would be Azeri, although its population was predominantly Armenian. However, oblast status implied a significant devolution of political power, and thus a certain degree of autonomy vis-à-vis the Soviet Socialist Republics. Throughout the Soviet era, both countries were emptied of their respective ethnic minorities, except in the Nagorno-Karabakh Oblast where 94% of the population was still Armenian in 1990. When the first war ended in 1994 with a ceasefire, the 2000-year-old Armenian population on the shores of the Caspian Sea disappeared, while the Muslim presence dating back to the Seljuk conquests suffered the same fate within the borders of present-day Armenia.

These disappearances are accompanied by the destruction of the respective heritages. When Heydar Aliyev signed the end of the conflict, he realized that this new country did not have the financial means to continue the war to regain its territorial integrity. He therefore decided to sign the first “contract of the century” to exploit the natural resources that had been coveted by the ruling forces for centuries. 13 companies from 8 countries (Azerbaijan, Turkey, the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Norway, Russia and Saudi Arabia) set out to exploit Azeri hydrocarbons. Heydar Aliyev died in 2003, succeeded by his son Ilham. He has continued his father’s energy policy by signing a new “contract of the century”. To regain full territoriality, the regime had to arm itself, and obtain a green light from the Western powers.

Baku began to make a name for itself in Europe through caviar diplomacy. Various members of parliament in different countries, including the European Parliament, received gifts and invitations to the Caucasian capital. These bribes help to extend the Aliyev regime’s influence abroad. The Western press is remarkably silent on the repeated human rights violations and fraudulent elections taking place in Azerbaijan – a simple comparison with the media’s treatment of the same crimes committed by Russia is enough to assess the extent of the omerta enjoyed by the Azeri regime.

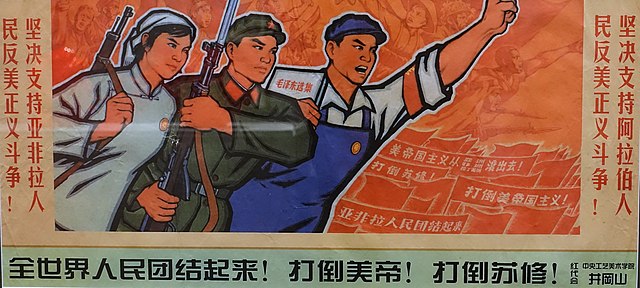

Having bought the silence of European diplomats, Aliyev was able to build an army equipped with cutting-edge technology imported from the USA, Israel, Russia and, above all, Turkey. The Turkish-Azeri alliance goes back a long way. As far back as the 1920s, Turkey supported the inter-ethnic massacres committed by Azeris against Armenians – the latter being allies of the Russians. Heydar Aliyev is credited with popularizing the slogan “two states, one nation”, which is based on the shared language between Turks and Azeris, said to have emerged from the Seljuk conquests around the first millennium – though this account makes a few historical shortcuts.

This alliance was reactivated in 2020, when the Turkish army was authorized to deploy in the Nakhichevan enclave. Several thousand jihadists were transferred from Turkish-occupied northern Syria to support the Azeri army. Faced with the magnitude of the Azeri army and its intertwined international networks, Armenia was unable to fight on equal terms. Thus, in 44 days, the Armenian army was routed – and the Azeri advance turned into a massacre, before being halted by Russian military intervention. [1]

Pipelines, Armenophobia and NATO

The ceasefire agreement of November 10, 2020 led to the departure of Armenian troops from Azerbaijan and the maintenance of a corridor between what remains of the oblast and Armenia (the Lachin corridor). 2,000 Russian troops were deployed to maintain security, while all Armenian prisoners, as well as the wounded and remains of the deceased, were to be returned. In Armenia, point 8 of the agreement is a particularly bitter pill to swallow: “All economic and transport links in the region will be restored. The Republic of Armenia guarantees the security of transport links between the eastern regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Autonomous Republic of Nakhichevan, in order to organize the free movement of citizens, vehicles and goods in both directions. Transport control will be exercised by border guards of the Russian Federal Security Service”. For the Azeri side, this is the equivalent of the Lachin corridor, which would provide continuity between the two Azeri territories separated by the Syunik region. A few weeks later, a pro-Erdogan newspaper revealed the plans between the two regimes.

A new gas pipeline is envisioned to double exports to the European Union by avoiding transit through Georgia [2]. New infrastructure – also mentioned in point 9 of the ceasefire agreement – would also be prepared to connect the Turkish market to Asia. This corridor, so ardently desired by the Ankara-Baku axis, has not yet seen the light of day – or at least one can say that it is still far removed from Panturkic aims.

At the same time, Armenophobia is reaching new heights. During an address to the nation in October 2020, Aliyev declared: “I said we would drive [Armenians] off our land like dogs, and we did it”. He went on to contest Armenian territory: “I said they had to leave our lands, or we would expel them by force. And it happened. The same will happen to the Zangezour corridor […] which was taken from us 101 years ago”. A “victory museum” opened in Baku, displaying vehicles taken from the enemy and the combat equipment of Armenians killed on battlefields. They were represented in the form of grotesque wax mannequins with distorted features.

The European Union’s leniency towards Aliyev raises questions. While Azerbaijan is in the “Western” camp and is keen to strengthen its cooperation with NATO, it is not aligned with Europe and the US in every respect. Numerous Russian companies are present in Azerbaijan through the intermediary of Lukoil, which holds a major stake in the country’s main gas field. As for the increase in Azeri gas exports since the Ukrainian conflict, it’s hard not to observe this as the consequence of increased gas imports from Russia.

Will the Europeans and Americans allow Aliyev to continue his war of conquest against Armenia, considered too close to Russia? Nothing is less certain. American leaders seem to have sensed an opportunity in the South Caucasus, which would enable them to increase their hold on the international gas market. Armenia occupies a strategic position in this region. Bordering Iran, its territory abounds in natural gas, and numerous development projects are underway to supply the European Union and the Asian market. In the south, as mentioned previously, new projects on the Baku-Ankara axis could achieve this. Similarly, from the south towards the north, an Iranian gas pipeline could reach Georgia, where the Azeri pipeline that exports gas to Europe is already located.

Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Armenia a few days after the Azeri offensive – again supported by Turkey – seems to indicate that a new energy era is dawning, and that new military alliances will be formed to protect the interests of the world’s former leading gas exporter. The United States could become the guarantor of Armenia’s security, putting Russia in an unprecedented position of weakness. Russia was absent during the Azeri incursion into Armenia, despite repeated requests for support from Yerevan. Russia and Armenia are both members of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which is supposed to implicate its members in a defensive military alliance in case of an attack. Putin’s desire to weaken President Pachinian, who is too close to the West for his taste, is obvious. Weakened as well by the invasion of Ukraine, it is unlikely that Vladimir Putin’s Russia will multiply its fronts and engage in a costly proxy war with Azerbaijan – with which it incidentally enjoys cordial relations.

However, this does not mean that geopolitical blocs are being reconfigured. For the time being, the rapprochement between the United States and Armenia is largely symbolic, and Azerbaijan remains a privileged partner of Western states. Beyond the rhetoric, Azerbaijan continues to supply itself with the weapons of NATO and its allies, and supplies the European Union with gas. Once again, Europeans demonstrate their inability to deploy outside the zones of American influence and to defend an independent diplomatic approach.

This article first appeared in French on the LVSL website. Translation: Florent Marchais. Reproduced with permission.

Notes :

[1] In the territories inhabited by the 150,000 Armenians in what remains of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Oblast.

[2] A buffer state between the European Union and Azerbaijan, considered to be in Russia’s orbit.