I.

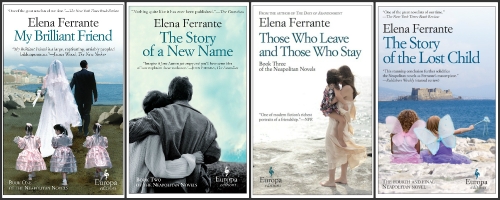

Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet is an international sensation. The depth of the storyline, its vivid descriptions of feeling, its frantic pace, and the intricacy of Neapolitan culture interwoven into the personal narratives have been discussed, dissected, and showered with praise by better writers than myself.

Yet what has been overlooked is an adequate appraisal of the politics that emanates at each step. Whether it is the force of the dominant ideology, limited space in columns or complacency about history that causes reviewers to overlook the fascinating political currents running through the quartet, they deserve attention for a modern left that is perpetually haunted by the ghosts of its past iterations. In this sense, the quartet functions as a history lesson on an understudied polity: post-war Italy.

The tumultuous, tragic lives of Lenu (Elena Greco) and Lila (Raffella Cerullo) are shaped by the tug of war between ascendant communism and the unspoken union between Christian Democracy and organised crime. Born into an impoverished, working-class neighbourhood of Naples under the shadow of the “two great forces of Italian reaction”, the two girls find in each other a source of intellectual and moral sustenance.

It begins with Lila throwing Lenu’s doll into a cellar belonging to the dreaded Camorrist loan shark of the neighbourhood, Don Achille Carracci. Lenu retaliates in kind. Lila forces Lenu to go with her to demand their dolls back from Don Achille. Walking up the stairs to Don Achille’s apartment, Lila offers her hand to encourage Lenu and, though deeply afraid of what the terrifying man might do, Lenu grasps it. Their fates would be intertwined for the next six decades.

When Don Achille is confronted by Lila, he is amused by her boldness and gives the girls some money to buy new dolls, but they buy instead a used copy of ‘Little Women’. A creative and literary passion within the two girls starts, with Lenu acutely self-aware of her intellectual shortcomings. It inspires a contest between the two to read voraciously from the school library and they push each other to excel academically.

For a Global North generation born after the “end of history”, it is difficult to grasp the life-changing impact of social guarantees like schooling. The distinctly feminist lesson of the quartet manifests through the educational divergence between the two. Though Lenu is acutely aware that her friend is the true prodigy, possessing an intellect and a will that is uncontainable, it is Lenu’s parents who, after rancorous quarrels, support her education after the age of 12. Lila’s family recognises no financial benefit of paying for a girl’s education through books and stationery. Their fates diverge even if their friendship remains. Ferrante effortlessly melds the themes of class and patriarchy into one.

Lenu goes on to excel and eventually study at the Normale in Pisa, publishing successful novels and writing columns for national newspapers, while her friend sees her passions steadily ground under the mill of misogyny and poverty. Yet she gravitates back to the culture of the stradone and her childhood milieu. Chief among whom is Nino Sarratore, The brilliant son of part-time poet and journalist Donato Sarratore. Both men have a profound influence on Lenu’s intellectual passions, with Nino serving as an object of desire for both Lila and Lenu.

II.

Reading about Lenu’s exceptional rise into a petit bourgeois milieu from the humblest beginnings reminded me of an excellent essay by John Merrick discussing the conflicts of working-class achievement. The character’s infiltration of the bourgeois society of Italy is intensely unsettling and she resists, with varying degrees of success, to not let herself be unmoored from the stradone of Naples.

The central marker of this cultural gulf is expressed through the Neapolitan dialect, which serves as a private language for the purest interlocution of thoughts between the inhabitants of the neighbourhood and also as a target for class prejudices – something that Lenu is continually subjected to due to the imperfection of her adopted visage of refinement. Consequently, she experiences the inner conflicts of pursuing dreams in a world where those of her ilk are forbidden to dream, of inhabiting exalted spaces designed to exclude her, to achieve ends that become more ephemeral the closer she gets to achieving them.

Today, regional and linguistic distinctions often enshrine a system of class-cultural stratification, fomenting resentments that find terrible expression through the ascendant far-right in the absence of a coherent leftist movement like that of the PCI (Italian Communist Party). The social and cultural divide that grows in today’s societies requires us to understand and empathise with the web of emotions that working people feel and are made to feel, as modernity drags them through the seas of change like a forgotten appendage.

Ferrante’s literary style inverts the standard depiction of political narratives, where political actors and events are central and participating characters peripheral. Instead we are given minimal exposure to the political heavyweights of the era such as Rudi Dutschke, Enrico Berlinguer, Aldo Moro, and Pier Paolo Pasolini. We experience the 1968 movement as an individual situated in the period mixed in with the tumults of ordinary life, giving the narrative a pedagogical quality.

III.

To what extent was Lila’s intellectual promise destroyed by the misogyny that prevailed in deeply conservative Catholic Italy? Entire episodes in the story made me reminisce about family and social life in my native Pakistan. Perhaps Pakistanis and Italians are not so different and we simply exist in a state of asynchronicity. But what about the deep poverty described in the novel? Lila is incredibly bright, but on account of her being female her intelligence goes unrecognised and uninvested. Would a more mediocre and male Lila be given the chance to flourish?

Enzo Scanno, the son of the fruit seller who returns traumatised from military service, becomes a successful IT professional despite his childhood reputation as the class dunce. Yet he would be the first to credit his success to the brilliance of Lila’s tutelage and creativity. It is the grit of this exceptional woman that breaks through the class ceiling society imposes upon her, and perhaps in the process robbing the working class of an organic leader. We would be remiss if we were to assume the totality of patriarchy in deciding the fate of Ferrante’s women: Lila defies containment. She spends her entire life in Naples, yet her spirit and her acts are felt across borders. Her geographical confinement proves no hindrance to her evolution. This uncontainable nature echoes Beauvoirian ideas of woman. A woman that is at various times impetuous, imperious, and indifferent. Envious, competitive, and mean. Yet enduringly loyal, generous with her time and money, determined to surmount the socioeconomic challenges of Naples, the neighbourhood, her own conservative family, and the Camorrist brothers who threaten her life and her livelihood. Though men try to break her through physical, economic, and sexual abuse, she defies them and exacts in due time her revenge.

She is not a woman, but Woman; in all the multiplicity of Woman. In her defiant multiplicity is expressed a feminist message that demands that women be able to practice their full subjectivity without constraints. That they may not be Vestal maidens, doting mothers, loyal companions, resilient fighters or any combination thereof. This yearning to be uncontainable is a powerful (re)expression of second-wave feminism. These are lost lessons that demand reiteration for a new generation to appraise them and shape their thinking.

IV.

Ferrante reveals the evolution of work in Italy after the war through the lens of proletarian life. We see Lila’s father start out as a cottage entrepreneur, making and repairing shoes, while the wealthier Solaras make money through a pastry shop and loansharking, among other unknown criminal enterprises. Sandwiched in between is the upwardly mobile son of Don Achille, Stefano Carracci, who runs a grocery store and harbours ambitions to expand. These ambitions of upward mobility spur him to enter financial agreements with the Solaras, a choice that will seed his ruin. Three sets of entrepreneurs with contradictory interests, that are resolved in time with the Solaras totally dominating the other two.

Workers and their working conditions feature prominently, with Lila’s life of toil in the Soccavo sausage factory providing a grim insight into an all-too-often romanticised industrial working-class existence. We learn through Lila’s organising in the workplace how solidarity is never guaranteed, but won through blood and sweat – quite literally. The union of fascism, bosses, and organised crime becomes logically consistent when we witness the confluence of their economic interests. The working class is never supine and it resists through militancy in the workplace and beyond, most sharply through the Red Brigades that capture and execute the Christian Democrat Prime Minister Aldo Moro.

In the interwoven narration of this shocking historical event, orchestrated in the aftermath of the Historic Compromise between the PCI and the Christian Democrats, the intellectual tensions of timeless leftist debates are brought to the fore. An upwardly mobile petit bourgeois intellectual strata starts to form and perhaps the Red Brigades were acutely aware of the splintering this would inspire in the politics of the Italian working class, foreshadowing the dissolution of the PCI itself. Seen in this light, the execution of Moro seems like a desperate act in the face of modernity’s unceasing encroachment on their present. Lila and Enzo are beginning their careers as IT specialists in the same period, finally escaping the economic confines of working-class destitution even though they remain wedded to the social sanctuary of their neighbourhood.

The march of modernity, the “necessary” political compromises it would entail, the visions of a more prosperous future unfettered by the paralysing war of aggression between left and right; these themes find their expression most faithfully through Nino Sarratore. He encapsulates the essence of the third way that would come to dominate the long 90s. The social and romantic carnage left in his wake in the lives of Lila and Lenu mirror his political evolution. In the words of Lenu’s mother-in-law, the quintessential left bourgeois intellectual Adele Airota, ‘for a person who is no one to become someone is more important than anything else’.

Nino’s arriviste character leads him to the Italian Chamber of Deputies. The third way will eventually prevail and Nino will be one of its self-aggrandising leaders. The PCI would dissolve itself in 1991.

V.

History, when it has passed, inclines towards obscurity, not clarity. It is part of the left’s function to remember beyond the ordinary lifespans of humans, to bear the torch that illuminates the past and to craft a narrative of it that makes it vivid. Ferrante does this through the urgent realism of her narrative. For us on the left she has gifted us with words that can help us explain, relate, and articulate a narrative for our present, unceasing, encroaching modernity. We are the generation that succeeds her characters and so through this insight into their history, we may learn to practice that optimism of the will that Gramsci had advocated a generation earlier.

Editor’s note: for further reading on Gramsci’s analysis of fascism, we recommend the following texts:

- Walter L. Adamson, Gramsci’s interpretation of Fascism

- Lucio Colletti, Antonio Gramsci and the Italian Revolution

- Marxist Leninist Archive Reactionary Subversiveness