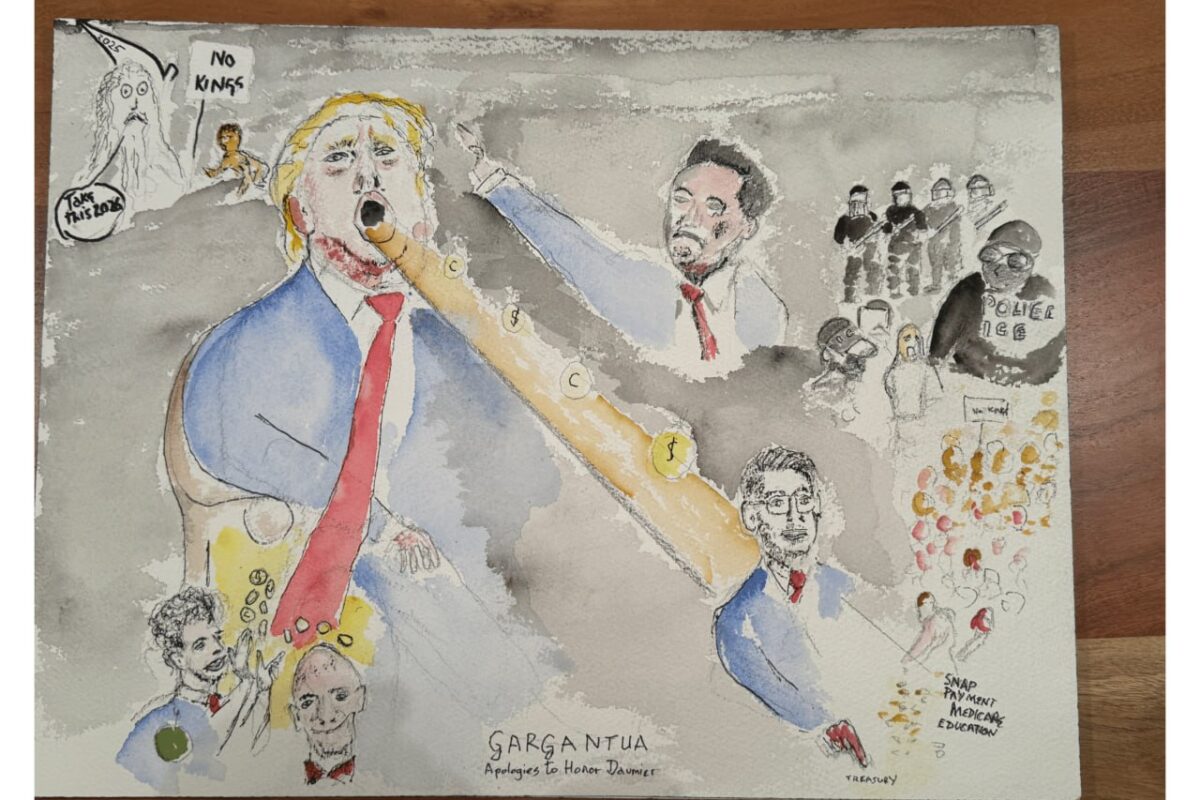

Two years ago, a group of Berlin-based people came together under the name Palästina Solidarität Archiv, and started documenting and cataloguing materials related to the Palestine solidarity movement in the city, and the state repression they were and are subjected to. Their collection includes interviews with activists, photographs and videos from protests, state communications, posters and stickers. This weekend (17-19 October), a small part of it was displayed for the public for the first time, in an exhibition called “Memory Protocol – Oct 2023: Archiving Solidarity & Countering State Narratives”, hosted at AGIT. On the final day of the exhibition, we hosted an interview with one of the group’s members, to discuss their process, Germany’s state repression and ultimately, the use of archiving as a producer of counter narratives and a resistance tool, both for the present and for the future.

Thanks for talking with us today. Can you start by telling us more about the Palästina Solidarität Archiv?

The Palästina Solidarität Archiv is a project to document the state oppression and police brutality against the pro-Palestinian movement, that we have been witnessing in Berlin for the last two-three years; but also the resistance of the people and how they are fighting back. Documenting includes videos, pictures, communications between police and activists (for example, demonstration bans), and physical materials like stickers and banners. The archive also includes oral testimonies, from both newly engaged people in activism, and people who have been around for a long time—this has allowed us to look into the past, all the way from the 80s to today. We have more than 30 hours of interviews, and will still collect more. We hope it’s a long-term project. I’m glad we can see some of the fruits of the project right now, but my hope is that it would be beneficial in the future.

Where did the idea come from? How did this group come together?

The archive was an initiative from people that were part of Palästina Kampagne, a group with people coming from different backgrounds. Archiving means a lot in a Palestinian context, where many archives were destroyed by the Israeli military, plundered or taken into Israeli archives and made classified and therefore inaccessible to the public, and to Jewish comrades due to the documentation done during the Holocaust which proved so important many years after. We are a very diverse group. Everyone brings their own expertises, experience, and their own background—it’s amazing to be able to learn from so many people.

The idea for the archive came around October 7, 2023 (although even before that the state and the media were using false narratives), because it became really important to be able to document our own history, what we were experiencing, to document our resistance—this is something that the state would never do. They only document what they portray as our criminal acts. One day, hopefully, we will be able to use this archive to do other projects, research, and help bring accountability around people who are involved in and facilitated the genocide. For the start of the project, we applied for a residency at AGIT, which supports different types of archiving work and other projects and exhibitions. We got the residency and some funding, but all the people working on the project are volunteers. AGIT has been a safe space for us to work and to interact with other groups, and to benefit from the experience of other archives.

How many people are involved in the archive, and what is the structure of the group like?

When it started as an initiative from Palästina Kampagne, it was around five people. Soon after it started, we realized how much work it involved, so it evolved into an independent project—also to be a project for the whole community, and to see how it could benefit other groups. Now we are almost 20 people, but it varies, depending on capacity at any given moment. There’s a core group which coordinates, and around 13 people who help with different things, like digital security, video editing, pixelation, etc. There’s also a lot of people collecting stickers from all over the city and bringing them to the archive.

You mentioned the connection with other groups. Is this also a way to connect different movements in the city?

We would like it to be a community archive—meaning that the archive should have the ability to adapt according to what the community needs. However, how do we find community? With what kind of engagement? What kind of say do different communities have in the archive? The idea is to be able to work with all the groups involved in the Palestine movement in the city and help as much as we can, but I wouldn’t say that we, as an archive, can bring the groups together. Even though our work is, of course, political work, it has a very specific goal with the archive—so our goal is not to bring groups together, but to be able to work with the different groups.

Can you tell us more about the exhibition that was hosted at AGIT this weekend?

We hope that one day, the material we’ve been collecting—which is a huge amount—can be publicly accessible for different people, groups and organisations. Right now, it’s difficult to make it public, because we are still living in a state of repression and the criminalisation rate is not only very high, but also very unpredictable—we don’t know what the state can regard as illegal, and what kind of repression one might face—so we need to take care of the people in the community. That’s why, until now, we have not published any material online, and we will not do that anytime soon. However, we still wanted to show that the archive exists and is still collecting material, and can do collaborations and exhibitions—even without publishing all the materials.

For this first exhibition, we decided to begin where the idea for the project started as well: October 2023. The amount of material we have is insane. We focused on the first weeks after October 7, because at that point, the repression was unprecedented: the state of Berlin—and only Berlin—imposed a general ban on all pro-Palestine activities, including demonstrations, rallies, and any type of solidarity showing. They even prohibited vigils, where people just wanted to light up candles. We noticed that many people forgot how intense, overwhelming and surreal that was. A lot of people that visited the exhibition looked at the materials and started remembering that they were actually there, but didn’t really have it in their memory anymore. Besides showing the repression, in the exhibition we tried to recreate the development of the resistance of the movement here—we showcase the timeline throughout those weeks, how people kept going with persistence and resilience, how they kept registering demonstrations and using different tactics, until they were able to overcome the ban.

Building on that, the exhibition also includes an interactive map. How has the visitors’ reaction and engagement been?

The feedback has been really positive—people were glad that someone was archiving. They liked the construction of the exhibition itself, and how we showed the timeline. We are positively surprised with the engagement, this gives us motivation to keep going. In the beginning we were anxious, about how many people would show up, and how they would react. People are asking us how they can get involved in the project, and different groups asked to collaborate as well. At the same time, it is not an easy thing—the exhibition doesn’t have a lot of material, but once you start reading it and understand everything that was going on, it’s a tough topic. For most people, it was really emotional.

It’s important how it’s framed about being not only about repression, but equally about resistance, and how to fight back in the particular context of the city where we are in. In that sense, why is archiving so important?

Resisting is not something that the state likes. Our resistance and our narrative is nothing that the state-influenced media would archive, or even show to begin with. So it’s really important for us to be able to actually know what happened back then, to have our own version of the story. It’s also important for people to see their own accomplishments—many have been posting pictures and videos online, but it’s mostly about state repression and police brutality, and sometimes small achievements. But what we are able to do with the archive is to actually reconstruct the whole timeline and visually show how everything came to be. That is important to have, to motivate us to keep fighting, as otherwise, people might get demotivated or frustrated, because we don’t see the difference we are making. Once the situation allows us to go public, this might help bring some people to court, see some accountability. I don’t know what kind of “justice” would make things right, but it might serve as proof that we were fighting against the state’s fascism and repression.

Another thing this enables is to be able to contradict the police’s false narratives: when you look at the documents they provide, there is no logic; sometimes it’s just blatant lies. But now, we are able to provide videos and other documents for people who are facing charges and going to court; and these materials actually show that what the police claims is completely false.

We often associate archives with something that is looking at the past; but the examples you’ve shared show they can have an impact in things like the legal system—and operating in the here and now.

It depends on the case that is being archived, and what can be publicly accessible. But archiving the repression is happening in parallel with the repression itself, which is ongoing. We hope to one day publish most of our materials after the repression has stopped or declined, so we will be able to look into the past in a way, but we can still make use of it now. The most important for the here and now is that defendants and their lawyers can request footage from us that could be relevant in their trials. We also work with trusted researchers and journalists who want to research and write about repression.

The exhibition is called Memory Protocol. Why did you choose this title?

It comes from the term Gedächtnisprotokoll [log of events reconstructed from the author’s memory], which is a specific paper with questions for people to share what they experienced after a demonstration, an arrest, or something else they have witnessed. It can be really overwhelming when a person is experiencing brutality from the police or any other kind of repression. With that adrenaline rush, one can forget a lot of things. So a memory protocol makes it easier to answer a couple of questions, which might help afterwards. That’s why we use that term.

We also have an interactive map at the exhibition where people can add their own experience from what they can remember—even though now is not directly after October 2023, we are still close enough to that time, to bring memories and archive them before they get lost. The way we constructed the exhibition, it’s just like the protocol—we bring people into a setting that is similar to the one in October 2023, hoping to refresh their memories and be able to extract some more things for the archive.

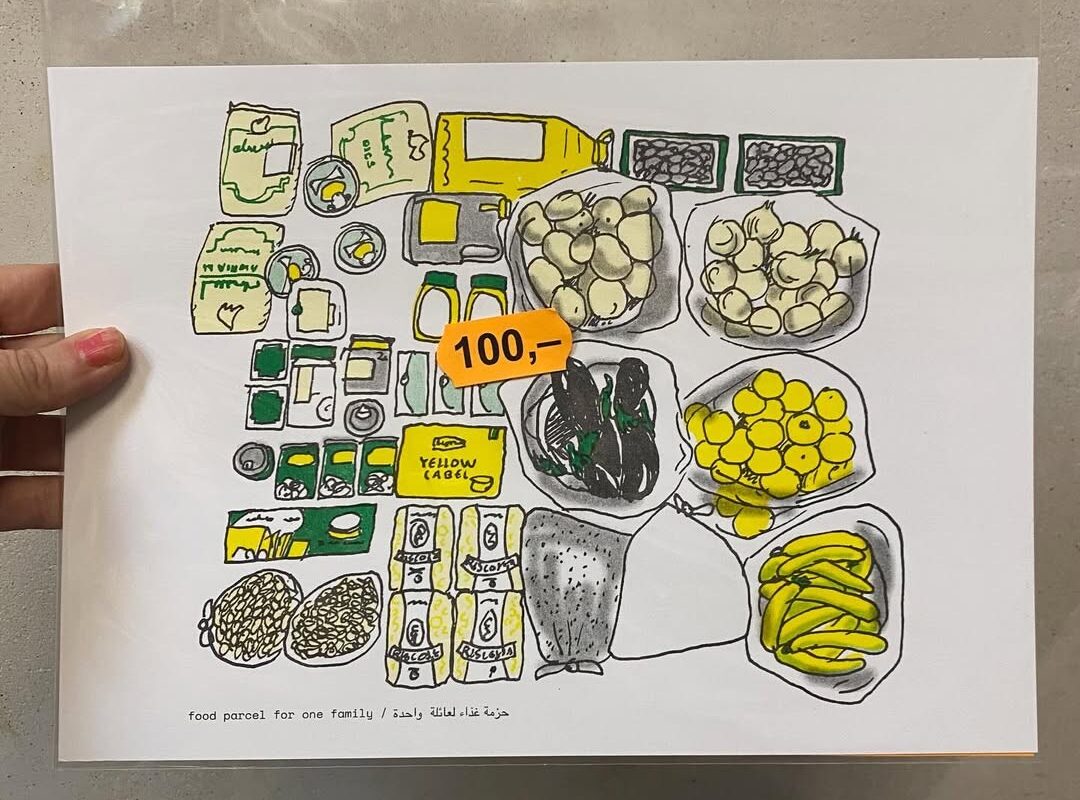

You work in English, German and Arabic. Arabic feels particularly important, since it’s been criminalised in Berlin. The exhibition also has the three languages, it’s not available just for German-speaking audiences.

A lot of groups are using Arabic for their activism and organising, which is amazing to see, since the Arabic language, and the Arabic identity itself has been criminalised here. In some demonstrations the Arabic language was banned, but also Hebrew. I remember a demonstration in Potsdamer Platz, where an Arab comrade and an Israeli comrade were both not allowed to hold speeches in their own languages. The bans in this country have reached absurd levels—not only languages, but Germany has also banned the use of certain colors [the Palestinian flag colors], geometric shapes, fruits…

For the archive, we want the materials to be accessible to everyone—that’s why we are trying our best to work in all three languages. We translate the police documents, and hold and translate the interviews into English, German and Arabic. Using Arabic at this time is also empowering for the community—people with an immigration background, especially Arab and Muslim people, who are more affected by the repression than others. So it’s good they can still engage with their own identity.

For the people who have missed the exhibition this weekend, what can they expect to see in the future? How can they get involved?

For the people that missed the exhibition, unfortunately it was only here for a weekend, but we will make available online some photos and a video. For the archive, people can get involved and bring in their own expertises—in digital security, audio and video editing, etc. They can join the group and support in any ways they can. They can also send us materials to be added to the archive.

In terms of what to expect from us, as I said, there won’t be any publication of the materials soon, but people can expect other similar exhibitions, and we are also thinking about workshops—for example, things needed to be able to set up an archive, or how to film demonstrations (we get a lot of videos we can’t actually use, because there is a certain way to document events and a specific type of information we need to see in a video so it’s of any use); but also some collaborations. We are still not sure about how all of this will look like.