It seems we consume everything and everyone today, including ourselves. We have lost a clear sense of what freedom is. If we do not trade our labour for it, it is unattainable. Much like democracy: without an abundant budget, it collapses. Paradoxically, fascism often begins for free. In such circumstances, tyrants are always cast as the saviours of the nation in the first act. Once we transition to the next act, we can no longer distinguish reality from myth and fabricated truths, as if the storage of centuries of knowledge had been erased and the operating system of each of us reset, leaving us to absorb whatever is served at the moment. We are losing our grasp inhabiting a liminal space—not one of ritual, but an unexpiring period of semi-blindness and semi-life.

In this light, a book like this must remain within daily reach—as a reminder of an anti-tyrannical lifestyle in times when tyrants hold global power, peoples are oppressed as if genocide were not occurring, and the world persists in silence, preoccupied with consumerism instead of demanding demanding the termination of brutalities and accountability. We are, after all, intelligent beings and human enough (although Franco Bifo Berardi noted at Miss Read Art Book Fair in Berlin that humanity has become ridiculed) to envision a wiser future, informed by historical and contemporary research, refusing to allow anyone to monopolise our ethical reason and empathetic heart.

Snyder approaches tyranny ontologically, recalling times when women and animals were regarded as equivalent, and tracing its evolution through slavery, colonialism, and imperialism. According to him, European history has witnessed three major democratic moments: following the First World War in 1918, after the Second World War in 1945, and after the end of Communism in 1989. Meanwhile, economics and global trade have fostered mass politics, while idealised, quasi-divine leaders have collapsed democracies into right-wing authoritarianism and fascism—rejecting reason in the name of “reason” and turning back to mythomania and messianic promises of salvation from the Other, usually evil and external. Somewhat simplistically, Snyder equates fascism and communism, a tendency I regard as problematic within mainstream liberal philosophy, though I will not dwell on this further.

The book encourages us to apply the knowledge acquired in the twentieth century, offering twenty lessons for resisting contemporary threats to democracy. Notably, Snyder references Orwell, Arendt, and Kiš within a shared anti-totalitarian context, reminding us of these thinkers in case we have forgotten—or never encountered them, as may be true for Danilo Kiš from Yugoslavia/Serbia. Kiš was persecuted as an intellectual and labeled an enemy of the state, a fate that resonates today with the precarious position of universities and critical thought worldwide. A concrete example can be found in Serbia, where students and their professors have, for ten months, resisted with educated courage and principled disobedience. They accepted the consequences and refused to sit passively in a waiting room for justice and “anti-fascist living”. No other approach would work with tyrants, especially within neoliberal systems that undermine solidarity and leave no one safe, often through the selective application of law. When states and international institutions fail to protect us, we must exercise self-protection. Serbian students, together with those who joined them, have successfully embodied Snyder’s twenty lessons. In the following text, I aim to substantiate this, quoting the introduction to each lesson.

1. DO NOT OBEY IN ADVANCE

“Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do.” (p.17)

This behaviour begins locally and then spreads across the country like a self-managed network of obedience, becoming an unquestioned constant in the political system. Citizens believe such conduct preserves them and their families, but in reality, it only entrenches economic and socio-political slavery.

By contrast, Serbian students and their allies have inverted this “game”: they teach power what it can no longer do, compelling the repressive government to confront the very wishes and demands that students themselves imposed. In doing so, they expose the regime’s illegal and criminal deeds, signalling the necessity for each citizen to ask whether their own servile complicity places them in violation of the law.

2. DEFEND INSTITUTIONS

“It is institutions that help us to preserve decency. They need our help as well. Do not speak of “our institutions” unless you make them yours by acting on their behalf. Institutions do not protect themselves. They fall one after another unless each is defended from the beginning. So choose an institution you care about — a court, a newspaper, a law, a labor union — and take its side.” (p.22)

Serbia is a kidnapped state with institutions that are consequently compromised. Students have resolved to reclaim them, persistently reminding these bodies of their fundamental functions. It is an arduous struggle against a deeply entrenched system of corruption that encompasses the courts, the Prosecutor’s Office, the Regulatory Authority for Electronic Media (REM), the Republic Electoral Commission (RIK), and Radio Television of Serbia (RTS). In the process, students have also built connections with various labour unions. Yet much work remains before they can truly declare: the institutions are ours, and it is our responsibility to safeguard them henceforth.

3. BEWARE THE ONE-PARTY STATE

“The parties that remade states and suppressed rivals were not omnipotent from the start. They exploited a historic moment to make political life impossible for their opponents. So support the multi-party system and defend the rules of democratic elections. Vote in local and state elections while you can. Consider running for office.” (p.26)

This is precisely what has happened in Serbia, persisting now for thirteen years. The opposition has been dismantled, and politics has become a realm that decent citizens avoid. In response, students have initiated a repoliticisation of the public sphere, effectively proving the theory: the private is political. Given the stage of the Leviathan in Serbia—marked by its ignorance and defamation of opponents—students and their allies have demanded both republic and presidential elections, despite the clearly undemocratic conditions already confirmed by the European Union in December 2024.

Meanwhile, rebelling citizens have organised themselves and built grassroots connections across the country, many of whom are prepared to monitor and protect the very exercise of elections. The president, who once called elections at will with unshakeable confidence in his victory, now speaks only of the possibility of elections in 2027. At the same time, students are preparing their own political list of non-compromised representatives and experts. Since the opposition in Serbia is far too weak to run an election without serious reorganisation and strategic planning, many individuals who would never have considered entering the political arena are now more than ready to participate.

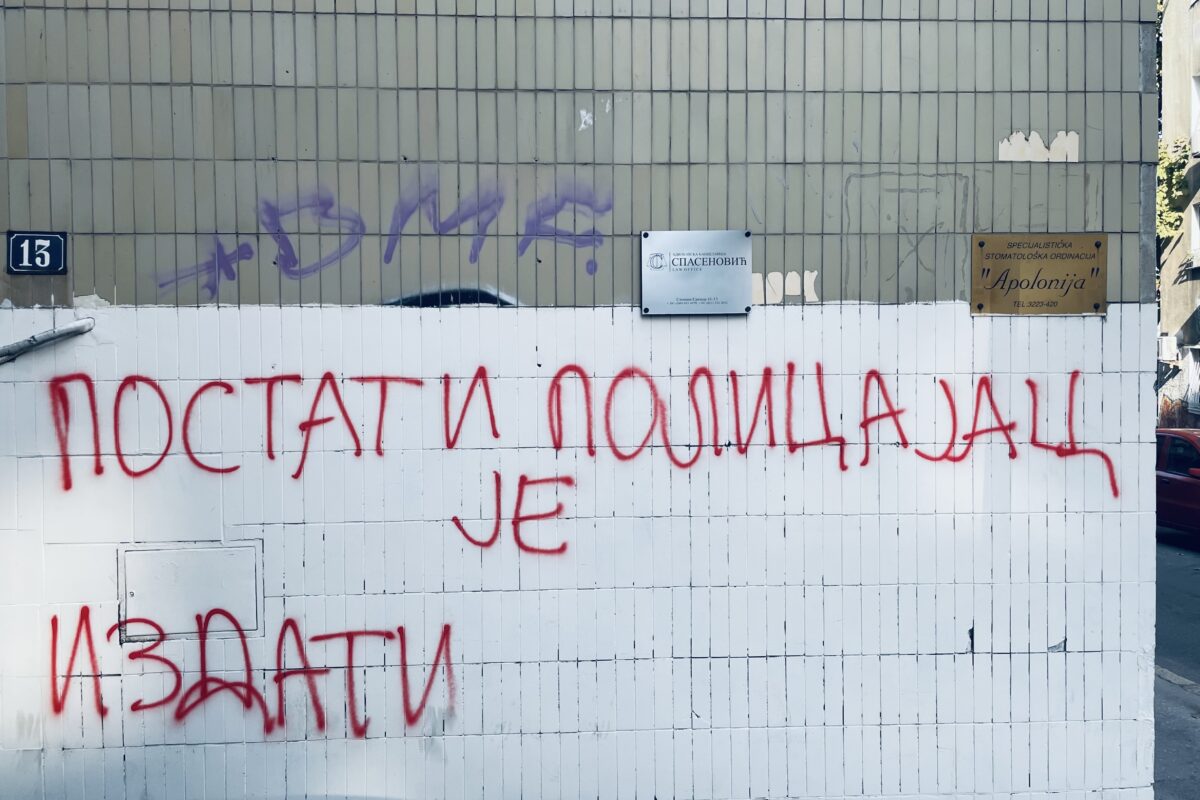

4. TAKE RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE FACE OF THE WORLD

“The symbols of today enable the reality of tomorrow. Notice the swastikas and the other signs of hate. Do not look away, and do not get used to them. Remove them yourself and set an example for others to do so.” (p.32)

Aware of the self-proclaimed Serbian Progressive Party State, students are risking everything for absolute democracy, giving their country a hand-made “facelift” by reclaiming its flag, anthem, and Republic Day. This achievement was reinforced by long, nationwide marches that united citizens in committed solidarity.

At the same time, the regime regularly labels students and their supporters as fascists, terrorists, Nazis, and the like—culminating in a large banner displayed in the center of Belgrade that read: “Better ćaci (a neologism for the regime’s proponents) than Nazi”, with the swastika visibly crossed out. Two women destroyed the banner, but they were arrested—not the mastermind who had used the prohibited symbol under Serbian law. Thinking and acting beyond the local, students also rode bicycles and ran a relay marathon to Strasbourg, i.e., Brussels, reminding the EU of its own democratic values.

5. REMEMBER PROFESSIONAL ETHICS

“When political leaders set a negative example, professional commitments to just practice become more important. It is hard to subvert a rule-of-law state without lawyers, or to hold show trials without judges. Authoritarians need obedient civil servants, and concentration camp directors seek businessmen interested in cheap labor.” (p.38)

Professionally ethical, students are doing their job: engaging in critical thinking, bridging past, present, and future, and prioritising futurabilities. When they encounter gaps in their competencies, they turn to professors and other professionals for assistance. There is no shame in not knowing—only in pretending to possess expertise in everything (cf. the Serbian president). Among the first supporters of the students was the Bar Association of Serbia. Together, they demonstrated to the public that the law is not inherently against them; rather, citizens’ indoctrinated ignorance and mistrust have led them to abandon reliance on it. In addition, lawyers and judges who serve state power are now being publicly denounced and will be held accountable as soon as the juridical system is restored and the executive is separated from the legislative branch.

Extrapolating to a more global level, European business interests are focused on Serbian lithium, while Serbian autocrats locally sell the narrative of immense economic prosperity, “beautifying” the harsh reality that this country is also a site of cheap labor extraction, as if we cannot consult independent scientists and corporate lawyers.

6. BE WARY OF PARAMILITARIES

“When the men with guns who have always claimed to be against the system start wearing uniforms and marching with torches and pictures of leaders, the end is nigh. When the pro-leader paramilitary and the official police and military intermingle, the end has come.” (p.42)

Although not paramilitaries in the strict sense, plainclothes police, state-organised hooligans, and loyalists function as informal instruments of state violence and intimidation. Since the police usually act not as neutral enforcers of the constitution and law but as servants of a single individual, this is blatant proof that democracy is absent in Serbia.

Fortunately, students and their supporters have recognised and mobilised their own disruptive agencies, successfully deconstructing the uniforms and accessories that have, for decades, been celebrated here—even allowing war criminals to be hailed as national heroes. They have read the police oath aloud in the streets, face-to-face with fully equipped officers, often masked with balaclavas. Such menace can be paralysing for civil disobedience, yet in this case it has clearly accelerated the regime’s self-destruction.

7. BE REFLECTIVE IF YOU MUST BE ARMED

“If you carry a weapon in public service, may God bless you and keep you. But know that evils of the past involved policemen and soldiers finding themselves, one day, doing irregular things. Be ready to say no!” (p.47)

This is an alarming reality. The forces of state control deploy unnecessary violence against unarmed and peaceful citizens—particularly students and high school pupils—who never initiate attacks but at most attempt self-protection, often linguistically. One such instance was an invitation to the police to march alongside the protesters in order to secure order and peace.

The students’ main weapons are their own bodies, hands raised, which the police regularly misuse as a pretext to beat them without reason. And yet, the students persist, reciting a poem by the late Serbian academic Ljubomir Simović (1985):

“I will rise,

crushed, shattered, oppressed,

at steel armies

with a wooden sword…”

This raises an urgent question: how long will the police forces continue to obey the orders of a regime acting against its own people, determined only to prolong its stay in power, while the EU turns a blind eye? Since protesters consistently remind the police of their legal obligations, they may soon begin quoting Snyder as well.

8. STAND OUT

“Someone has to. It is easy to follow along. It can feel strange to do or say something different. But without that unease, there is no freedom. Remember Rosa Parks. The moment you set an example, the spell of the status quo is broken, and others will follow.” (p.51)

Students are practicing this with the utmost determination. They have stood out and articulated a different reality, opening horizons of new possibilities for the country. Fully aware of the possible consequences, they have shown a readiness to confront tabloids and corrupt politicians intelligently, dismantling their lies, plagiarism, and other manipulations. Their actions have liberated many other citizens, both domestically and diasporically, and even inspired parallel struggles, such as in Georgia.

People are following, but this time with eyes wide open, as the movement encourages everyone to reflect and participate directly, contributing to a shared goal and embodying plurality through collaborative diversity.

9. BE KIND TO OUR LANGUAGE

“Avoid pronouncing the phrases everyone else does. Think up your own way of speaking, even if only to convey that thing you think everyone is saying. Make an effort to separate yourself from the internet. Read books.” (p.59)

Students first read the Blockade Cook. They generously introduced us to a new constitution-based mantra—“You’re not authorised!”—as a way of addressing the president. They emancipated all the dialects of Serbia in a gesture of linguistic solidarity that strengthened connection and trust across communities. They simply began calling things by their names—a subversive act in a country of multilayered propaganda. At once digital and analogue, they embody a practice of factual agitation.

10. BELIEVE IN TRUTH

“To abandon facts is to abandon freedom. If nothing is true, then no one can criticize power, because there is no basis upon which to do so. If nothing is true, then all is spectacle. The biggest wallet pays for the most blinding lights.” (p.65)

Students managed to “de-fake” news and dismantle the spread of alternative facts in the public sphere. They decoded the regime’s spectacle, often parodying it and debunking its lies in real time, in highly creative and sharp ways. This is surely one of the main reasons why so many citizens have joined their side—the side where truth resides.

11. INVESTIGATE

“Figure things out for yourself. Spend more time with long articles. Subsidize investigative journalism by subscribing to print media. Realize that some of what is on the internet is there to harm you. Learn about sites that investigate propaganda campaigns (some of which come from abroad). Take responsibility for what you communicate with others.” (p.72)

Students are the newest socio-political investigators. In light of the long-standing absence of genuine journalism in the main public sphere, they have competently assumed this role—consulting with experts and drawing on the support of their professors. Numerous NGOs engaged in investigative journalism, socio-political monitoring, and research also stand by their side. Their inquiries extend beyond politics to economics and ecology. While exposing the harms associated with the internet, they also employ it as an ally in a country where media freedom is under constant threat. They refrain from communicating until facts are verified, paying careful attention to timing and to language itself, which has already been blatantly polluted by the dominant actors of political discourse.

12. MAKE EYE CONTACT AND SMALL TALK

“This is not just polite. It is part of being a citizen and a responsible member of society. It is also a way to stay in touch with your surroundings, break down social barriers, and understand whom you should and should not trust. If we enter a culture of denunciation, you will want to know the psychological landscape of your daily life.” (p.81)

I would argue that this is an area in which the students possess exceptional skills, demonstrated through acts of countrywide intergenerational hugging and collective crying. They made people in remote parts of Serbia feel seen and relevant. By reintroducing fundamental human values, they reclaimed their significance for strengthening the social body. They reminded us that solidarity dismantles alienation and shifts fear onto the side of the oppressor, who will no longer so easily perpetuate cycles of corruption and intimidation. They also restored the diaspora’s sense of belonging to the home country. In doing so, students have definitively liberated citizens from psychological and moral self-oppression.

13. PRACTICE CORPOREAL POLITICS

“Power wants your body softening in your chair and your emotions dissipating on the screen. Get outside. Put your body in unfamiliar places with unfamiliar people. Make new friends and march with them.” (p.83)

We assumed that Generation Z was active only in the digital world, but we were wonderfully mistaken. Students have transformed Serbian public space into a parliament of body politics. They resist, demand, and disrupt. They have created a collective, disobedient body that—though vulnerable and heavily precarised in a non-democratic state—refuses invisibility and silence. In the longer run, this multiplies the occasions to be bold and daring.

14. ESTABLISH A PRIVATE LIFE

“Nastier rulers will use what they know about you to push you around. Scrub your computer of malware on a regular basis. Remember that email is skywriting. Consider using alternative forms of the internet, or simply using it less.

Have personal exchanges in person. For the same reason, resolve any legal trouble. Tyrants seek the hook on which to hang you. Try not to have hooks.” (p.87)

The students have never presented themselves as experts; they are still learning by doing, particularly after being illegally spied on and persecuted without any justification from the state. They actively share their knowledge, and in this way began disseminating information on how to keep certain matters private. Lawyers have provided significant assistance in this process. Citizens are gradually becoming educated about their own rights, developing familiarity with the law and the constitution after long experiencing them as instruments of disadvantage. Recognising the protective functions of the state apparatus, and learning to employ them effectively, certainly requires both engagement and careful reflection.

15. CONTRIBUTE TO GOOD CAUSES

“Be active in organizations, political or not, that express your own view of life. Pick a charity or two and set up autopay. Then you will have made a free choice that supports civil society and helps others to do good.” (p.92)

Over the past ten months, students have consistently directed their efforts toward socially beneficial causes. Organised in plenums, they actively engage in the management of everyday life, whether within their faculties, affiliated institutions, or public spaces across Serbia. In doing so, they set a compelling example for citizens, demonstrating the possibilities of participation and self-determination in both local and broader communities (e.g., citizens’ assemblies).

Their initiatives have included fundraising for colleagues’ medical treatments (a widespread necessity in Serbia, where SMS-based donations are often relied upon), organising charity fairs, and mobilising aid for those affected by recent wildfires across several regions. When individuals are persecuted by the state for their socio-political positions, the students do not abandon them; instead, they coordinate support both locally and within the diaspora, as exemplified by the case of a bus driver.

16. LEARN FROM PEERS IN OTHER COUNTRIES

“Keep up your friendships abroad, or make new friends in other countries. The present difficulties in the United States are an element of a larger trend. And no country is going to find a solution by itself. Make sure you and your family have passports.” (p.95)

Authentically friendly and open-minded, students delight in building new friendships. Some even cycled and ran a relay marathon across Europe to facilitate mutual exchange of knowledge and information. In the 21st century!? They can be a bit silly, too. Their connections extend to peers engaged in parallel struggles in Georgia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovakia, Turkey, Hungary, and beyond. This is a generation that does not aspire to abandon the country, even though they are fully aware that the current regime plays dirty and unlawfully. They are therefore prepared to protect both themselves and others, recognising that this fight is a marathon, not a sprint.

At the same time, I would gladly see other countries—especially their students—learning from them: resisting state oppression against freedom of speech and the right to peaceful assembly, and reasoning beyond the so-called reason of the state itself.

17. LISTEN FOR DANGEROUS WORDS

“Be alert to the use of the words extremism and terrorism. Be alive to the fatal notions of emergency and exception. Be angry about the treacherous use of patriotic vocabulary.” (p.99)

As individuals who have undergone a state-induced transition—from “good, but manipulated kids” to “fascists and terrorists determined to dismantle the constitutional order”—students understand the intricate relationship between language and power, even before engaging with Foucault, Derrida, Althusser, and others. They have shown that what the president attempts to sell as ballot bait is nothing more than patrioticised nationalism, and in doing so, they have undertaken crucial conceptual redefinitions. Though deeply angered, they remain neither rude nor manipulative, nor do they step into the regime-nourished petit bourgeois garden.

18. BE CALM WHEN THE UNTHINKABLE ARRIVES

“Modern tyranny is terror management. When the terrorist attack comes, remember that authoritarians exploit such events in order to consolidate power. The sudden disaster that requires the end of checks and balances, the dissolution of opposition parties, the suspension of freedom of expression, the right to a fair trial, and so on, is the oldest trick in the Hitlerian book. Do not fall for it.” (p.103)

When the state practiced sonic terror, students remained calm and helped others compose themselves. When the state attributed its own acts of terror to disobedient citizens, it was immediately exposed, leading to yet another loss of authority for the regime. They categorically refuse to emulate Hitler’s students—though some pro-regime professors have willingly become just that. Instead, they have resolved to keep rising, bringing us along with them. They leave no one behind, not a single antifascist.

19. BE A PATRIOT

“Set a good example of what America means for the generations to come. They will need it.” (p.111)

Students love their country, and this time their brains are not draining abroad. It makes the tyrants panic. They are already planning for their future children and have made the diaspora feel welcome to return without regrets. To be a patriot, perhaps, also means living one’s mother tongue lively.

20. BE AS COURAGEOUS AS YOU CAN

“If none of us is prepared to die for freedom, then all of us will die under tyranny.” (p.115)

They are braver than they themselves could have imagined. They are preparing us for freedom. Now we all proclaim loudly: THERE’S NO GOING BACK! WE WILL WIN THIS! And the people of the Balkans carry mountains in their hearts. Have you ever seen anything more enduring than that geography?

As Stanley (2018) emphasised, fascism also operates through anti-intellectualism and the systematic attack on experts—a dynamic Serbian students directly confront by mobilising knowledge, critical thought, and solidarity. Yet Braidotti and Dolphijn (2023) remind us: “The crucial question however is: who and how many are ‘we,’ those who desire an anti-fascist life?” The students’ example provisionally answers that even under extreme repression, “we” can be created, expanded, and sustained through courageous, collective action—believing in a brighter future as scientists, rather than as religious or other fanatics.

Snyder’s political theory proves far more potent in practice.