After the Second World War and the political chaos it brought forth, the countries of the global South fought for independence from the genocidal imperialist powers. A process of decolonisation began, which albeit temporarily, restored hope and dignity to billions of people. Country after country expelled its colonisers and recovered its resources and territories after centuries of exploitation.

Decolonisation, land redistribution and access to education for the liberated peoples was the ideal breeding ground for the spread of socialist and communist ideologies in many countries: from Vietnam to Indonesia, from Egypt to Congo, from Cuba to Guatemala.

Indonesia, under the leadership of Sukarno, declared its independence from the Netherlands in August 1945. After four years of struggle and uncertainty, the Dutch finally transferred sovereignty of the country to President Sukarno, a revolutionary, nationalist and deeply anti-imperialist politician.

During his years in power (1949-1967), Sukarno progressively shifted to the left, collaborating with the government and providing support and protection to the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), at the time, the largest communist party outside the communist countries.

Sukarno was a skilled diplomat who, together with Gamal Abdel Nasser, president of Egypt, and Jawaharlal Nehru, prime minister of India, managed to bring together most of the countries undergoing decolonisation in Asia and Africa, as well as some in South America, in Indonesia at the legendary Bandung Conference in April 1955.

In the city of Bandung, Java, these countries proclaimed themselves to be the third world, that is, countries independent of the opposing axes: Yankee capitalism and Soviet communism. In what became known as the Spirit of Bandung, a new idea of global order was conceived, distancing itself from the colonial first world and the continuation of imperialism with soviet overtones by the second world.

At this Afro-Asian conference, 10 fundamental principles were agreed upon as the basis for international relations, including respect for human rights and anti-racism, the right to self-determination of peoples, and the right to armed struggle in defence of that right.

Unlike the countries of the first world, whose idea of nationhood is based on race or language, the countries of the third world based their nationalism on anti-colonial struggle and social justice. These countries, which are largely multicultural with thousands of indigenous languages spoken by the nearly 1.5 billion people represented at this conference, believed in a new international organisation and diplomacy beyond the colonisation they had suffered, where collective collaboration and coordination would stand up to the global economic order established by the rich countries. Sukarno himself linked the anti-imperialist struggle with anti-capitalism in his speeches.

Needless to say, most of the 29 participating countries paid dearly for their struggle for independence in the years and decades that followed, with wars, dictatorships and economic sanctions.

Sukarno’s anti-imperialist and redistributive policies irritated internal forces – the military and the radical Islamist factions within Indonesia, but also external ones, mainly the US. After the Second World War, the US was strengthening its areas of influence against the USSR, and its newly created CIA was beginning to perfect the tactics of internal and external sabotage that it would later apply savagely and with impunity, across the world.

Under US interference, Sukarno’s government was overthrown in 1967 in a brutal coup led by General Suharto. Literal rivers of blood flowed throughout the archipelago for two years. And so began a dictatorship that, just as the US wanted, eradicated communism and socialism from the country, killing between half a million and one and a half million communists and their families, in what experts describe as political genocide. It also eliminated or expelled the middle classes and intellectuals who were not sympathetic to the new pro-Yankee regime.

The country returned to large estates and semi-slave labour conditions, selling recently nationalised natural resources to the highest bidder, and Indonesia came to owe billions of dollars in debt to the IMF. Corruption, especially in higher ranks, like Suharto and his family, was the norm and the most cruel members of the military rose to the highest spheres of power.

One of them was General Prabowo Subianto, son-in-law of the dictator Suharto and known as the butcher of Timor for his fondness for torturing the peoples of East Timor and West Papua and one of those responsible for their genocide.

Suharto’s brutal dictatorship ended with his resignation in 1998. His vice president, B. Jusuf Habibie, held power until the first presidential elections in June 1999, in which Abdurrahman Wahid was elected president. In July 2001, he was forced to resign, and his vice president, Megawati Soekarnoputri, daughter of the first president Sukarno, became president of Indonesia.

In the election that followed, in April 2004, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono was elected president, a position he held until October 2014, when Joko Widodo was elected. A politician from a very humble background, he focused his presidency on the fight against social inequality and, in theory, against corruption.

The presidency of Joko Widodo (2014-2024), known as Jokowi, who has more socialist tendencies, was characterised by a strong focus on economic development and improving social welfare. From the outset, Jokowi promoted major infrastructure projects such as roads, bridges and airports, especially in remote areas, with the aim of reducing regional inequality and promoting connectivity. He promoted industrialisation and the transformation of Indonesia into a more productive and self-sufficient country, reducing dependence on raw material imports and the exploitation of cheap labour by multinationals.

In the social sphere, Jokowi strengthened assistance programmes such as universal health insurance (JKN), benefiting millions of Indonesians. He also implemented energy subsidy reforms, freeing up resources for education, health and infrastructure.

In the later years, Jokowi committed to the transition to renewable energy and the construction of a new capital, Nusantara, in Borneo, as a symbol of modernisation and decentralisation.

Despite these advances, his administration faced criticism for limited progress on human rights and freedom of expression, as well as religious and ethnic tensions and a clear lack of effective action against corruption.

In 2019, after winning his second election, Jokowi’s decision to appoint his rival in the last two elections, war criminal General Prawobo, as defence minister caused unrest among his supporters, who took to the streets in protest. His years as a minister undoubtedly helped to clean up his image as a democratic statesman.

In the 2024 presidential elections, in which Jokowi did not contest after having served two terms, the former defence minister, the butcher of East Timor, Prawobo, was elected president. The elections were clearly influenced by social media, especially TikTok, where the bloody general was portrayed as a good-natured, affable man who had come to change the corrupt system.

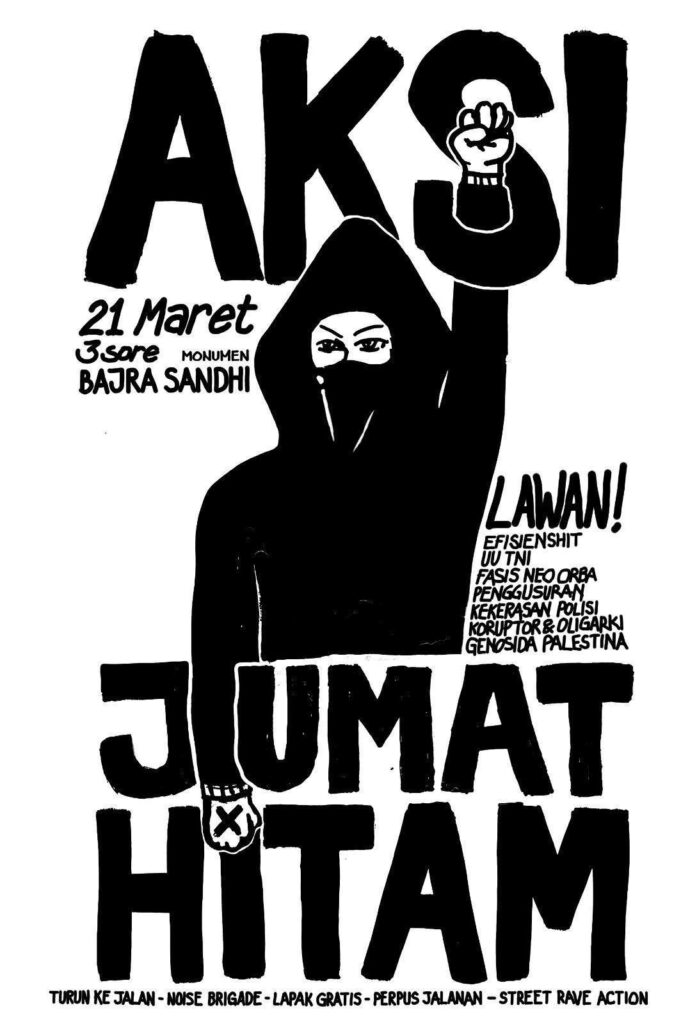

Since taking power, this general has carried out various reforms that are bringing this young democracy back to the brink of a military dictatorship. A series of legal reforms were the trigger for a new wave of protests in March 2025, a month that saw riots in the streets of hundreds of Indonesian cities. These protests were brutally attacked both by the police and the military, leading to dozens of injured people and the detention of hundreds of activists.

To explain the current situation, we interviewed a feminist anarchist activist who, for security reasons, spoke to us anonymously.

Interview: Indonesia’s Shift Under Prabowo – A Conversation with M.

Jokowi’s government certainly wasn’t perfect, but there were at least some efforts—however limited—towards fighting corruption, protecting the environment, and promoting social equality. Since Prabowo took power in 2024, what have been the biggest changes?

Since Prabowo Subianto assumed office as Indonesia’s president in October 2024, several significant policy shifts and political changes have emerged, contrasting with Jokowi’s administration in key areas such as governance, corruption eradication, social equality, and environmental protection.

Some of the biggest changes we have observed so far are in the areas of corruption, social welfare and inequality, environmental policies, democracy and human rights, international relationships and economic policies.

Let’s start with corruption—what’s changed there?

The Corruption Eradication Commission, or KPK, has been notably weakened. Even under Jokowi, the KPK was struggling—remember the controversial revisions to the KPK Law back in 2019—but it still managed to act on some high-profile cases.

Now, under Prabowo, there are growing concerns that the KPK is being politicized. There’s a real fear that it’s being used selectively—going after opposition figures while protecting allies. And the drop in high-profile prosecutions recently only adds to the concern. It raises serious questions about the administration’s actual commitment to anti-graft efforts.

What about social inequality and welfare? Has there been any progress?

Prabowo has actually expanded some of Jokowi’s social aid programs—like Bansos, the direct cash assistance—and it’s pretty clear that’s aimed at shoring up support among lower-income voters.

However, critics argue these programs are more politically motivated than structural reforms addressing inequality (e.g., land reform, labour rights). Minimum wage policies have seen little progressive change, with labour unions expressing dissatisfaction.

And environmental policy—where does Prabowo stand?

Jokowi’s administration had a mixed record, for e.g., there was the palm oil moratorium, but also support for nickel mining and deforestation. Prabowo seems to be rolling back protective measures even further– his government is increasing the number of permits for mining and agribusiness in sensitive areas. Also there is slower progress regarding renewable energy transition, compared to Jokowi’s push for solar and hydro-power. With respect to our climate commitments, the Prawobo government’s stance on carbon emissions and peatland protection has softened.

There’s been a lot of talk about democratic backsliding under Prabowo. What are you seeing?

We are seeing increasing authoritarian tendencies. There’s a harsher crackdown on protests, with reports of aggressive police action against demonstrators. There are concerns over pressure on critical journalists, reminiscent of Prabowo’s past ties to military repression and civil society groups—especially those focused on human rights or the environment—are facing new bureaucratic hurdles for advocacy work.

And how has Indonesia’s foreign policy changed since Prabowo took office?

Jokowi generally took a neutral, pragmatic approach—remaining neutral to both the U.S. and China, and focusing on economic diplomacy. Prabowo, by contrast, is much more nationalist and assertive.

We’re seeing stronger military posturing, a sharp rise in defense spending, and tougher rhetoric around maritime disputes. At the same time, he’s leaning more heavily on Chinese infrastructure investment, which raises red flags about debt dependency. Relations with Western democracies have cooled, especially on issues like human rights and environmental accountability.

What’s the approach on economic policy under Prabowo?

There’s still continuity in some areas—especially with Jokowi’s push for resource nationalism, like downstreaming nickel and bauxite. But Prabowo is relying more on state-owned enterprises and state intervention.

Unfortunately, bureaucratic reform isn’t a priority anymore. That means inefficiency and corruption in state-led projects are real risks. The concern is that we’ll see bigger spending with less oversight.

There is a continued focus on downstreaming, for e.g., nickel, bauxite processing, following Jokowi’s resource nationalism. But there are more state-led economic interventions, with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) playing a larger role, as well as reduced emphasis on bureaucratic reform, leading to concerns about inefficiency and corruption in state projects.

In summary, while Jokowi’s governance had flaws, his administration made some, albeit inconsistent progress in anti-corruption, social welfare, and environmental policy. Under Prabowo, corruption enforcement has weakened, environmental protections are declining, and democratic freedoms are shrinking, while populist welfare programs and nationalist economic policies dominate.

What’s the state of the opposition in parliament? Are they pushing back?

Since Prabowo Subianto took office, Indonesia’s opposition—primarily the PDI-P (Megawati’s party) and smaller factions like the Democratic Party (PD) and PKS—has been remarkably passive, often supporting the government’s controversial policies rather than mounting strong resistance. To put the complacency of the opposition in perspective – the House of Representatives is headed by Puan Maharani, the chairperson of the PDI-P, and the daughter of Megawati. There is also only fragmented resistance from civil society, with no major parliamentary pushback.

The controversy surrounding the revised Indonesian National Armed Forces (TNI) Law stems from its expansion of military influence into civilian governance. Critics argue that this move echoes the Dwi Fungsi (Dual Function) of the military during the Suharto era, which allowed the armed forces to dominate both security and civilian administration. The law permits active-duty officers to hold posts in civilian institutions, raising concerns about accountability and the erosion of democratic principles.

Protests have erupted across Indonesia, with activists fearing a return to militaristic rule and repression of civil liberties. The law’s hasty and non-transparent legislative process has also drawn criticism, with limited public participation fueling distrust. Many people warn that this could lead to abuses of power and impunity, which seems to be taking place now.

The revision of Indonesia’s TNI Law has sparked significant controversy, with critics warning it could reverse democratic reforms and re-militarize civilian life.

Speaking of the TNI Law revisions—what’s so controversial about them?

This law, termed Military Operations Other than War (OMSP), expands military role in civilian affairs, allowing TNI to engage in domestic security, disaster management, infrastructure projects, and even social programs—blurring the line between military and civilian governance. This revives the Suharto-era Dwi Fungsi (Dual Function) doctrine, where the military held political and economic power.

It weakens civilian oversight. The law removes requirements for parliamentary approval before deploying troops domestically. This has resulted in concerns that the president (Prabowo, a former general) could use TNI as a political tool, for instance, to suppress protests or opposition.

It is also a potential return to military business activities. The revised law opens loopholes for TNI to generate income through “partnerships” with private companies. This could revive the corrupt military-business complex of the New Order era (e.g., illegal logging, protection rackets).

The law also offers legal immunity for soldiers. Soldiers accused of crimes during operations may avoid civilian court trials, instead facing internal military tribunals. This raises fears of impunity for human rights violations (e.g., Papua conflict, past crackdowns on activists).

And how are people reacting?

People consider it a threat to democracy. The law erodes 25 years of post-Suharto reforms that had reduced military power in politics and Prabowo’s history as a hardline general (linked to 1998 kidnappings, Papua operations) underlies public distrust.

We are worried about repression. Activists fear the TNI could be used to crush protests (like in 2019 anti-government demonstrations), and silence dissent in regions like Papua and West Papua.

There are high corruption risks. Military involvement in business and infrastructure projects could lead to budget leaks (e.g., inflated contracts for allies), land grabbing (as seen in past TNI-backed projects), and so on.

That is why individuals, students, activists, human rights groups, public figures, academics, workers, legal experts, etc. are protesting, both in the streets and social media.

We all fear this is a return to the past. The government claims the law will help TNI to “modernize” and assist in development (e.g., building roads, schools). They also claim this law will ensure “national stability” against threats like separatism or cyber attacks. But this law marks a dangerous step toward re-militarizing Indonesian politics—a shift that benefits Prabowo’s grip on power and risks the repetition of the Suharto era abuses.

The opposition’s failure to block the TNI Law revisions symbolizes its broader submission to Prabowo’s agenda. Instead of acting as a check on power, most parties are avoiding confrontation, seeking future coalition deals, and are focused on survival rather than principled opposition.

As a result, Prabowo faces no strong parliamentary resistance, allowing him to consolidate power with minimal pushback.

Is there a strong opposition on the streets and who is leading it?

The strongest opposition clearly comes from civil society, comprising of people from diverse backgrounds. There is no single leader of this movement, as the public is united by a shared major concern and a common adversary. Each individual or group takes their own initiative, resisting in various ways and through different mediums. Although the efforts are carried out sporadically, the movement remains interconnected through a decentralized network.

What can people outside of Indonesia do to help?

The legalization of the revised UU TNI is not just an Indonesian problem—it is a global crisis. Indonesia plays a critical role in the fight for democracy and human rights in Southeast Asia and beyond. Therefore, the rise of militarism and neo-fascism in Indonesia threatens regional stability and sets a dangerous precedent for authoritarian regimes worldwide.

The people of Indonesia have fought too hard and sacrificed too much for democracy to allow their country to slide back into the militarism, corruption, and authoritarianism of the Suharto era. We cannot remain silent as neo-fascism rises in Indonesia. Together, we must resist, fight back, and stand in solidarity with the people of Indonesia.

We call on the international community to:

- Condemn Indonesia’s Authoritarian Turn: Publicly denounce the revised UU TNI and its threat to democracy and human rights.

- Stand with Indonesian Civil Society: Support the brave activists, students, and organizations resisting militarization and fighting for democracy.

- Impose Consequences: Use diplomatic, economic, and political tools to pressure the Indonesian government to repeal this law and uphold democratic principles.

- Monitor and Expose Abuses: Document and expose any human rights violations or anti-democratic actions resulting from the implementation of this law.

- Head over to the Indonesian embassy in your country and give them a heads-up, in whatever way you want!

In rage & solidarity,

M.

All Photos: @bara.api