“We don’t actually count the injured after a demonstration, normally only the dead”. This was the reply from a comrade in his 40s when I asked whether there were any more injured besides the two youngsters with casts. We were making our way back from the demonstration. The person on the seat next to us shared with us that one youth was now in hospital. They needed to examine whether everything is fine with his head but it looks like everything is alright, no cause for alarm, he said – visibly troubled – to soothe me.

Our collective participation in a demonstration on the third day of the Farkha Festival, organized by the Palestinian People’s Party Youth, is an expression of living solidarity that is characteristic of the festival. We encounter such solidarity when the Palestinian families in the village prepare their rooms us, so that we international guests can sleep in the most comfortable beds, or when they conjure up the best food, enough for 300 people, for those of us from the women’s collective.

The living, vigorous solidarity extends throughout the program: every mid-morning we support the village, together with Palestinian youth, with the upkeep of the infrastructure. One group renovates the municipal school, the next one builds a cement wall and yet another works in the village’s eco-garden. In a flash we come in contact with other festival participants, learn a few words of Arabic, hear how complicated their daily lives are, chat together. In the afternoon, we learn about the living conditions, the struggles of women in Palestinian society, and about the apartheid system in which the Palestinians have been forced to live.

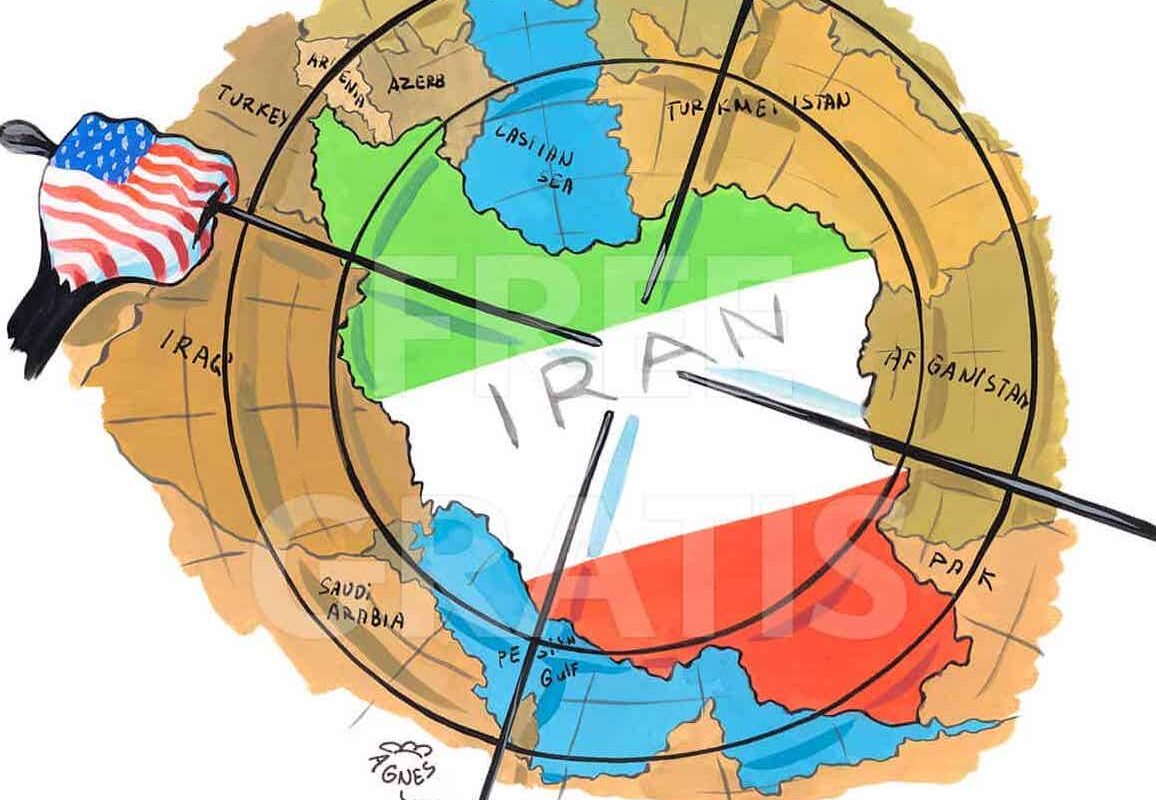

Israeli Settlements in the West Bank

Even before my journey, I found the concepts apartheid and settler-colonialism appropriate, based on my knowledge of the relationship between Palestine and Israel. But until now it was difficult to grasp. In Germany moral outrage is raised in a larger (if decreasing) part of my left political environment, accompanied by an extremely distorted reportage. Following the demonstration and our daily experience as “internationals” side by side with our Palestinian comrades, has caused any kind of insecurity and misgiving about the use of such terms to melt into the air.

What was the reason and course of a demonstration, from which three children with moderate injuries and approximately 30 further participants with tear gassed, red-eyed and sore eyes returned home? And how can it be explained, that all the injuries only surprised us German, Italian, Kurdish and Danish socialists, whereas all the people of the land viewed it as a daily outcome?

The reason for the demonstration in the village of Beit Dajan in the West Bank is the successive encroachments of the fields all around the village by a radical nationalist Israeli settlement. Israeli settlements in the West Bank are classified by the International Court of Justice and the United Nations as a violation of human rights. For the Palestinians settlements are accompanied with a loss of land or houses and an increasing Israeli military presence. For two years Palestinian residents have been protesting against the illegal expansion of a farm of one of the settlers, which may change the life of an entire village.

Machine guns aimed at us

Before the demo, our comrades assume that they will largely proceed freely, because the Israeli soldiers directly recognise us internationals through their cameras and drones. This will make them scale down their violence. However, they recommend us to place ourselves further back because we do not want to get hurt by tear gas which is fired at every demonstration.

When we get off the bus, I have to swallow. We are approximately 60 demonstrators, standing on a field road, with nothing around us but bushes, mounds, and soldiers positioned within them. They are directly in front of our procession and block the road, standing 30 metres away from us on the right and about 100 metres on the left. The machine guns are pointing towards us. The soldiers who are not pointing guns at us take photos of us. I feel fear for the first time in my life.

Ahead of the demonstration, the chants and speeches begin. I can barely make anything out, because I do not trust myself to go further ahead. Suddenly the people from the front rows begin to run. I hear shots – one, two, three tear gas grenades fall. I run as fast as I can, my knees wobble. “Rubber” bullet shots are added to the fray. These are metal bullets coated with rubber – “less lethal” but absolutely capable of inflicting deadly injuries.

When I turn around, all the demonstrators stand around a gas smoked ambulance that we had brought with us from the village. I see a stone flying in the direction of the soldiers. The shots, which have been documented on Youtube, go off again and land in the proximity of the ambulance. Our comrades come to us by the bus, one after the next. Some can barely walk or stand, slumped in front of the bus, disorientated by the teargas. The worst injured are transported away by a car.

Together in sorrow and frenzy

On the one hand, illegal machine gun and drone protected land theft, on the other chants and children throwing stones lifted off the ground. This could hardly be any further from the “Middle East conflict” and “Israel hate demonstrations” described by whitewashed German media reports.

While I sat shocked in the bus, the kids and the teenagers behind me begin to sing, to laugh, to go on with life. For them it was a normal demonstration. In the evening, the teenagers with the casts sit around and listen carefully to a talk. Like every evening, at some point everyone begins to sing, to chat; we dance a Palestinian dance with dozens of people.

The horrors of the day sink into oblivion. Suddenly I think I understand that the hospitality and the collectiveness that we experience here and the indescribable injustice that the people in Palestine experience are indeed two sides of the same coin. You suffer together, you give yourself over together into the exhilaration of the dancing and the singing.

Through the checkpoint to the mosque

The physical and psychic violence against the Palestinians that I encountered at the demonstration, extended from the first to the last day of our two and a half week weeks there. For example, during our day tour to al-Khalil (Hebron), where the oppression of Palestinians becomes visible as if under a magnifying glass. In al-Khalil 800 settlers under the protection of 2000 soldiers have ensconced themselves in the town centre.

We walk through a market street. At its end it becomes bustling. A queue of people begins to form because a checkpoint is located here. This is a turnstile, through which our travel group also must pass through in order to see another part of the city. Over and over, the turnstile pauses. Each time I am stuck for a few seconds until I can turn round. My heart beats faster when I am welcomed on the other side by soldiers with machine guns.

Here I realise that the people who had been pressured through the control like animals were all going to a mosque located right next to the soldiers’ station post. I stand on the small square, on which a few children want to sell us water. It is desolate and tears run down my eyes.

A feeling like imprisonment

The children gather near us and ask my travel companions why I am crying. Here once more, my reality collides with theirs. While I can barely endure the notion that the people here are cooped up by the Israeli military as if they were in prison, life between the soldiers is like a normality for the children of al-Khalil.

Here as well, stones are sometimes flung during disputes, causing the press to fall over itself with relish. Today it became clear in which moments this becomes frequent: the soldiers leave only the 100 metres of the street unblocked for Palestinians and guard the illegally occupied houses in the city centre. Sometimes they close an additional checkpoint without warning. This prevents some children from going to school. Waiting is an option, turning around is another. A third possibility, as rage grows, is picking up and throwing a stone.

Apartheid up close

In al-Khalil witnessed the following “conflict” situation: one side guards illegal settlements and fragments the city into a patchwork of checkpoints. Sometimes this side marches into mosques with boots and shoves the praying Muslims outside. The other side must go through an armed control checkpoint in order to pray. But they are denied access to some streets.

Today Israeli citizens live above Gold Street, and throw their garbage out of their windows. Old plastic chairs, diapers and food scraps are stacked a mete above the street below. Palestinians who can afford to, move away.

A Palestinian throwing a stone can be immediately taken into custody or shot. It is exceedingly uncommon for an Israeli soldier to be convicted for murdering a Palestinian. That is what apartheid means. I ask myself whether all journalists who write so bitterly against this definition have ever been here.

Hopeless in the Holy City

One of our last stations is Jerusalem. Against expectations it is rather calm. Only a day before our arrival hundreds of settlers forced themselves into the grounds of the al-Aqsa Mosque. After two weeks in Palestine our nerves are slowly reaching their limits. The hopelessness is setting in because we have experienced first-hand that anyone who goes on the streets against the illegitimate invasion of the mosque places their freedom or their life on the line.

Our friend leads us towards Sheikh Jarrah. the streets where the previous year an “anti-terror unit” of Israeli police forces and heavily armed soldiers forcibly evicted of a Palestinian family. This sparked off a mass movement to prevent it in Palestine and in the whole word.

Now we stand in front of the house, in which illegal Israeli settlers currently live. On the house is placed a Star of David, an Israeli flag, and about 10 cameras which are observing us. The Palestinian family that lived here sometimes sleeps in a car and at others with relatives. It is unlikely that they will be able to return to their house.

On the other side of the road, an even more drastic picture awaits us. Here, illegal settlers have taken up residence in the front garden of a small house belonging to a Palestinian family. I unsuccessfully try to imagine what it must be like to walk past my previous second house every morning, and not be able to do anything, although it has been illegally occupied for a year, there are no legal means to challenge this.

No religious conflict

An old gentleman walks along the street. Our friend introduces him to us as one of the neighbours. Like most people here, he has witnessed the protests against the forced evictions from start to finish. He explains that his grand-daughter has been sitting in prison for a year. She is accused of having used violence against an Israeli during the protests. She is 17 years old. He does not know when he will see her again.

I recall the speech of a Jewish comrade at the festival from a couple of days ago. He spoke about the difference between Judaism and the State of Israel, and of his solidarity towards Palestinian resistance. He described his anguish every time when Judaism and the Star of David that he wore on his wrist, are equated with Israel or with Zionism by German society. For him his identity is irreconcilable with the injustice that the State of Israel perpetrates against the Palestinians.

He received great applause for his speech. He felt no hint of scepticism based on his Jewish identity. Again and again it was explained to me at the festival that people have Jewish friends and neighbours with whom they live together.

Unending fury and a spark of hope

In the airplane I speculate that the thoughts of the checkpoints and machine guns will circle in my head every day back in Germany. Actually, it is the people who we met at the festival and on the field trips, that I think of the most: those who met us with so much warmth.

I think about the numerous grinning faces when we entered the festival grounds, about the girls and the boys who performed the dances, the collective cleaning of the school, which was interrupted every half hour with a dance, broom in hand. I think of all the families who brought us to the bus or organised for us to be picked up at the next stop by another family, so that nothing happened to us.

Despite the harrowing violence, I have returned with unending fury and a spark of hope. Because the majority of Palestinians radiate so much humanity and positivity that they will under no circumstances let themselves be expelled. One day, as it was repeatedly said to me, Palestine will be free.

This article originally appeared in German in critica. Translation Ali Khan. Reproduced with permission.

Julia will be talking about her experiences and showing film and photographs on Sunday, 20th November from 3pm in Bilgisaray, Oranienstraße 45.