This weekend, I attended the Gaza Tribunal, not the international event in Istanbul, but a conference in Berlin with the same name and held on the same weekend.

This tribunal was organised by Deutsche JuristInnen für das Völkerrecht (German Lawyers for Human Rights). With the subtitle “German Responsibility in the Light of Human Rights,” it heard expert reports on developments in Gaza, German Staatsräson, international perspectives, the role of the media, obligations under international law, legal consequences for Germany, and possible ways forward.

The tribunal largely focused on the legal aspects of the genocide. As a result, it was informative, often distressing, but also at times frustrating. Talking to a Palestinian friend afterwards, we both felt that it sometimes seemed more like a theoretical exercise for lawyers—more concerned with interpreting what has happened than with actively attempting to stop the genocide.

The tribunal followed South Africa’s attempt to prosecute Israel and Nicaragua’s case against Germany, both of which have been taken to the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Israel is being prosecuted for carrying out genocide, and Germany for “facilitating the commission” of that genocide. A related case—Gambia’s prosecution of Myanmar for genocide in the same court—was also frequently cited.

The case against Myanmar is due to be heard soon, with a ruling expected by late 2026 or early 2027. If Gambia wins, this will increase the likelihood of South Africa’s success. Even if Myanmar loses, the cases against Israel and Germany remain strong.

Genocide in Gaza. Repression in Germany

Various speakers painstakingly made the case for the prosecution. A recent UN report estimated that 680,000 people—29.5% of Gaza’s population—have died in the last two years. This figure includes both direct deaths caused by bombings and indirect deaths from disease and starvation. Diabetes, for instance, has now become a fatal condition in Gaza.

Eighteen thousand seven hundred Gazans have been kidnapped. These are not political prisoners who have languished in Israeli jails for years, but people captured since 7 October 2023.

The case against Germany rests on the fact that the German government continued to supply Israel with armaments despite a series of statements by Israeli politicians after 7 October that dehumanised Palestinians and threatened revenge on the population—indicating that genocide was a likely outcome.

Germany has also intensified its repression of supporters of Palestine, with 11,000 people charged in Berlin alone. Lawyer Alexander Gorski argued that this is part of a deliberate strategy to overwhelm protesters and wear them down.

Gorski described the case of his client, Hüseyin Doğru of red.media (whom The Left Berlin interviewed earlier this year). The German government has enabled the EU prosecution of Doğru because he spoke to all involved parties in his reporting on Gaza. Hüseyin interviewed and asked difficult questions of the PFLP and Hamas. This is the bare minimum we should expect of journalists. He is now not even allowed to hold a bank account.

The legal case

Canadian genocide expert Professor William Schabas gave a fascinating account of the history of genocide law, which Nicaragua, South Africa, and Gambia are using in their respective cases. The law was introduced in 1948 as an attempt to improve on the legal framework used in the Nuremberg trials.

The Nuremberg laws applied explicitly to racially motivated crimes committed during wartime. Nothing the Nazis did before September 1939 could be prosecuted. There was a good reason for this: with its history of slavery and segregation, the United States—backed by other countries with similar pasts—did not want to make itself liable to prosecution.

The new law was proposed by the United States’ nemesis, Cuba. It has only been ratified by around 70 countries—less than half of the world’s governments—and can only be implemented if both the prosecuting and prosecuted states are signatories. Both Germany and Nicaragua are among those 70, so a prosecution of Germany is possible.

Nicaragua argues that Germany is violating its own obligations to prevent genocide under international humanitarian law and the Genocide Convention. Its deposition demands the immediate cessation of actions facilitating the ethnic extermination of the Palestinian people.

Concretely, Nicaragua is asking the court to order Germany to halt all exports to Israel. This primarily affects weapons deliveries but could also include other forms of aid. Prosecution could have financial implications: when the Democratic Republic of Congo successfully prosecuted Uganda, Uganda was ordered to pay $325 million in reparations.

Is the legal system neutral?

All this sounds great, and we should welcome every instance where our side gains ground over theirs. But excuse my cynicism: I don’t believe the ICJ would be able to impose the same penalties on Germany and Israel that it did on Uganda even if it wanted to.

Professor Schabas himself conceded this point, noting that it is not within the ICJ’s remit to impose measures such as reparations or the ceding of territory. Such decisions are referred to the UN Security Council, which, as Schabas acknowledged, is effectively controlled by the US veto. And even if the ICJ were to rule in Nicaragua’s favour, Germany—backed by the United States—may simply choose to ignore the ruling.

The main open question, however, was how much we can expect change from within the system. Several speakers appeared to insist that our focus should remain on winning the ICJ cases. If we can prove Israel and Germany guilty, then we’ve won, right?

We need lawyers and mass movements

Let me make an analogy. Someone kills his wife and is taken to court. The court finds both him and his friend, who gave him the gun, guilty, but they are not punished and are not sent to jail. So, his friend gives him another gun, and he kills the rest of his family.

They are sent to court again. Once more, they are found guilty. Once more, they escape punishment. This might make it harder for them to get a bank loan, but it does nothing for the man’s wife and family—nor for anyone else he might kill after his friend provides him with a third gun.

A court victory means little in and of itself. Professor Schabas rightly pointed out that the recent UN ruling that Israel is carrying out genocide has made it easier for journalists to use the word genocide. This is true, as far as it goes, and it could play a small part in boosting the self-confidence of Palestinians and their supporters. But it misses the fact that the main reason journalists felt able to speak out was the mass movement on the streets.

Earlier in the day, Alexander Gorski noted that on 27 September, all of a sudden, the chant “From the river to the sea” became legal because so many people were shouting it. Gorski also said that he doesn’t trust the state or the legal system, and that all legal changes are the result of social movements.

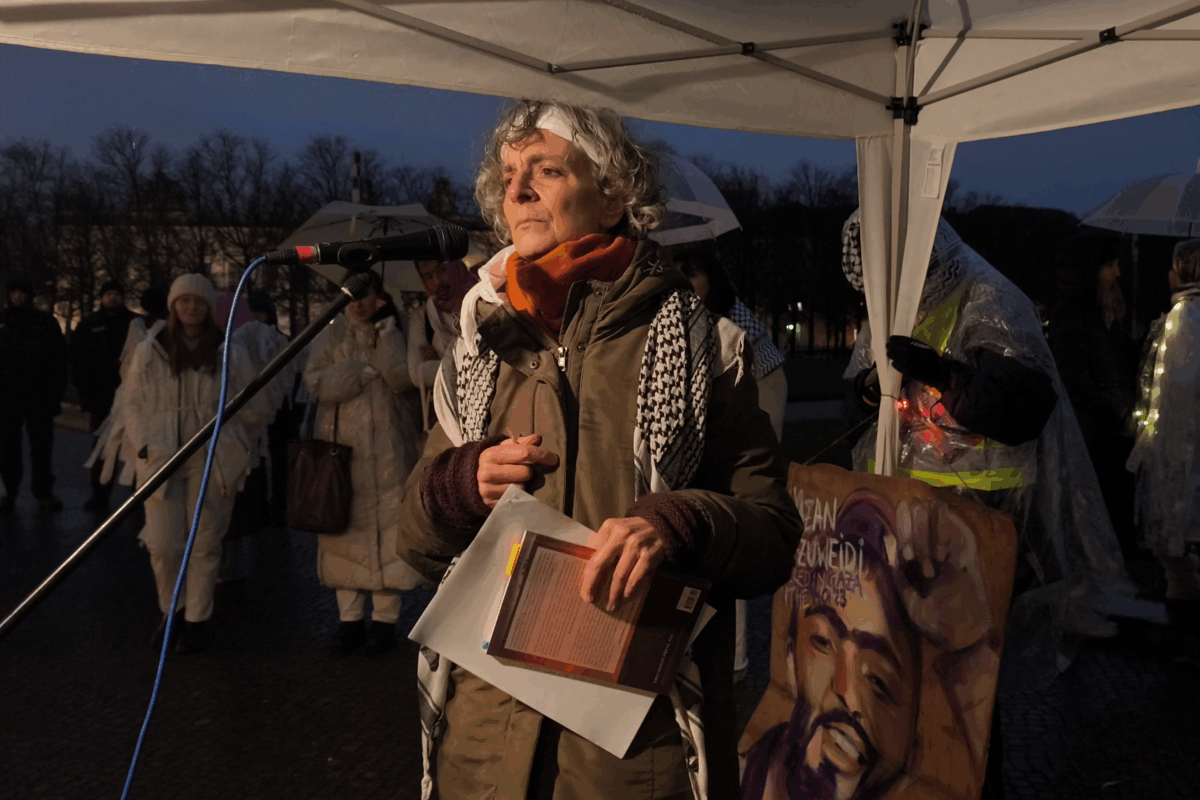

The final statement at the Gaza Tribunal was made by Palestinian lawyer Nadija Samour. Nadija said, “Human rights are not a harmless instrument. We must put them under pressure. Demo bans were beaten not by lawyers but by street mobilisations.” She pointed out that during the Gulf War, British activists were prosecuted for destroying weapons and won their case.

Nadija praised the Shut Elbit Down activists in Ulm who took matters into their own hands and shut down a weapons factory. At the same time, though, she pointed out that Ulm is not London, where the existence of a mass movement meant that when Palestine Action was criminalised, thousands of people were arrested in solidarity.

Conclusion

Legal challenges are an important part of our struggle for justice in Palestine, but they are not the only part. Essential court work has a dialectical relationship with street movements, as each complements the other. Our side is more likely to win a favourable court ruling if we have a vibrant and active movement on the streets—but that movement can also draw strength and energy from victories in the courts.

This relationship was recognised by several speakers at the Tribunal, most notably Alexander Gorski and all the participants of the final session, where Nadija was joined by Nahed Samour and Professor Dr. Isabel Feichtner. These were the most vibrant parts of the day, which at other times was bogged down in legal wrangling.

Court victories are not irrelevant, but they must be understood within the wider context of collective resistance. We all have our part to play in building a movement so large and determined that we can win—both on the streets and in the courts.

The Deutsche JuristInnen für das Völkerrecht have promised to release a report of the Tribunal soon. Notwithstanding any weaknesses, it will be an interesting read.