On the popular tourism island of Crete lies the ancient city of Chania. Inhabited since the Neolithic era, it is steeped in history with its pastel-coloured Venetian townhouses and Ottoman mosques. Revered for its rich history, white sandy beaches and Mediterranean cuisine, it’s considered the most beautiful city on the island and a top holiday destination.

Behind the façade of a dream-like escape from reality for European tourists lies an altogether different reality for the approximately 300 Sudanese refugees held in detention centres across Greece, facing life sentences in prison for crossing the Mediterranean to seek safety on European shores.

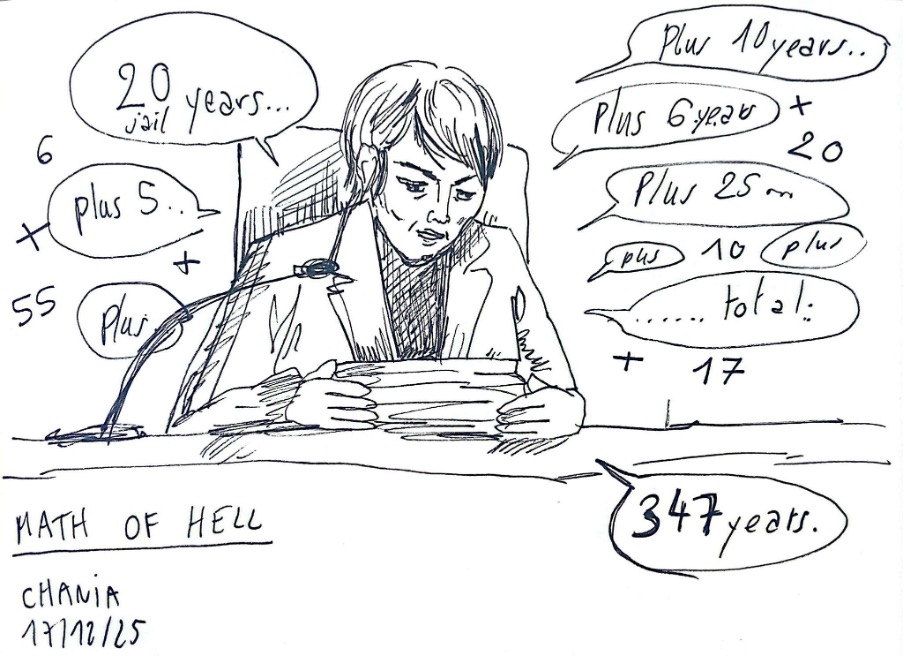

In recent weeks, the court in Chania has handed down several egregious sentences. On 1 December 2025, a 26-year-old looking for asylum received, after just minutes of the hearing, 335 years in prison and a fine of €200,000. The next sentence that the court handed down was 200 years.

Support groups de:criminalize, 50 out of Many, Mataris Sudan Solidarity Committee and Border Violence Monitoring Network, are among the few reporting on this violation of the United Nations’ 1951 Refugee Convention and raising awareness for the, oftentimes still underage, Sudanese boys facing life sentences in prison.

The exorbitant sentences are not unusual for the young men and boys seeking refuge in Crete. The refugees fleeing Sudan’s brutal war, surviving dangerous routes through the Sahara, Libya, and the Mediterranean Sea, are being held and sentenced on smuggling charges, for being forced to steer the boat under duress or being held responsible for other small tasks such as handing out water or holding a satellite navigation device.

A young Sudanese man imprisoned in Greece explains: ‘Most of us had no choice—either cooperate or risk our lives at sea.’

Despite their age and vulnerability, the boys are being tried as adults and smugglers. In recent weeks, the support groups reported, a 16-year-old boy was sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Under Greek law that came into effect in 2014, anyone steering a boat or appearing to assist in crossings faces charges of smuggling with sentences of up to 25 years per person transported. A 2023 study by Borderline Europe found that:

‘Trials lead to an average prison sentence of 46 years and a fine of 332.209 Euros’ and

‘52% of all convicted people are serving a prison sentence of 15 years to life’.

People imprisoned on smuggling charges now form the second largest group of inmates in Greek prisons.

The lawyer, Spyros Pantazis, defending one of the teenagers held in Greece, says: ‘The very tough anti-smuggling law has been a timeless governmental weapon to minimise illegal immigration. In reality, it is completely useless, only filling up Greek prisons with people who have no record or connection to criminal offences.’

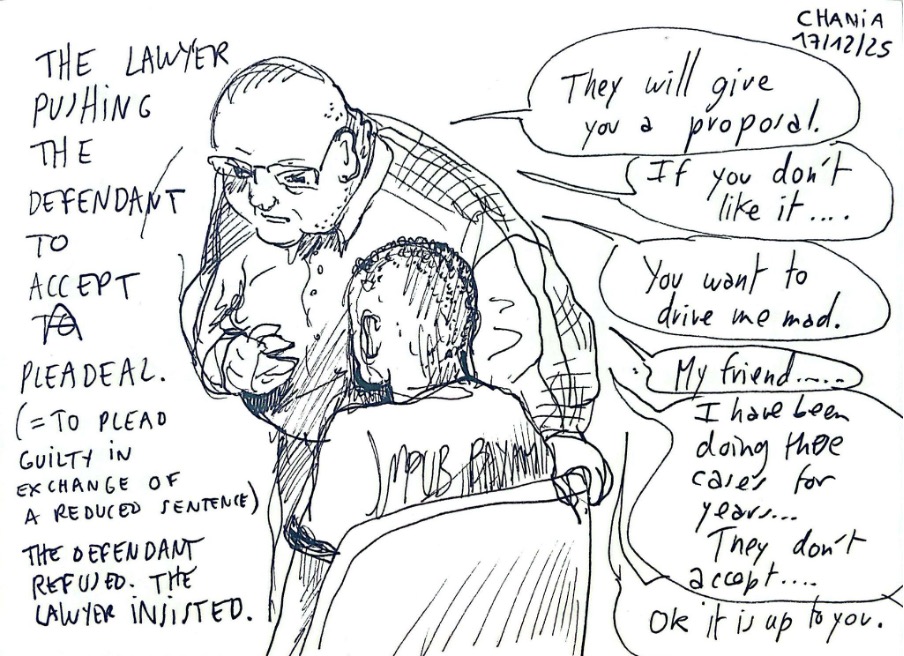

Meanwhile, de:criminalize reports, many of the accused are pressured by the court-appointed lawyers or prosecutors to make a plea deal with little to no knowledge of what that entails or what the consequences are. By signing a confession of guilt in exchange for a reduced sentence, the defendants, many of whom have already spent months or even years in pre-trial detention, forfeit ‘almost all chances of asylum’.

Almost every case in Chania is now settled through a plea deal. Sentences of hundreds of years, of which at least 25 must be served, are often reduced to a uniform 10 years behind bars under the plea deal.

The practice of plea deals, originally introduced to relieve the overburdened Greek legal system of insignificant cases, undermines the right to a fair trial for the Sudanese refugees. The irreversible guilty plea deal means there is no examination of evidence, witnesses or substantive review, nor the chance of appeal. Frequently, their court-appointed lawyers are ill-prepared and only meet shortly before the hearing, if not in the courtroom itself. The defendants have little to no opportunity to understand or reflect on the confession they are signing or the consequences thereof. Oftentimes, they do not have access to a qualified interpreter.

Borderline Europe reports: ‘Arrests and preliminary investigations are riddled with gross human rights violations; including arbitrary arrests, violence and coercion, little to no access to interpretation or legal support as well as problems in accessing the asylum procedure during detention.’

With 84% of cases studied for the 2023 Borderline Europe study resulting in pre-trial detention of an average of 8 months, the relentless violation of their human rights and with the prospect of prison sentences of hundreds of years, these vulnerable young men and boys signing plea deals are a foregone conclusion.

Recently, several defendants have been acquitted on the basis that, according to international law, asylum seekers must not be criminalised for their migration.

De:criminalize states, ‘These rulings make clear that in certain situations—for example, for people from countries with high asylum recognition rates—immediate release is not only theoretically possible but realistic.’

The 1951 Refugee Convention states that: ‘refugees should not be penalised for their illegal entry or stay. This recognises that the seeking of asylum can require refugees to breach immigration rules. Prohibited penalties might include being charged with immigration or criminal offences relating to the seeking of asylum or being arbitrarily detained purely on the basis of seeking asylum’.

Just this week, however, on 17 December 2025 31 defendants stood before the court in Chania facing decades in prison on smuggling charges. None were acquitted, most received 10-year sentences, some longer; ten cases were postponed. Birth certificates indicating that some defendants are minors were not accepted.

Images: Louise Truc.

As militarisation of EU borders increases and criminalisation of search and rescue is implemented, safe and legal routes disappear—the most vulnerable refugees are forced into ever more perilous journeys.

In the Guardian documentary How Europe’s immigration crackdown is fuelling smuggling gangs, Ashifa Kassam investigates whether the EU’s hardline policies are actually enriching the criminal gangs behind the scenes.

In the documentary, she flies over the Mediterranean with Omar El Manfalouti, a pilot at Humanitarian Pilots Initiative, where they encounter a vessel in distress. El Manfalouti explains: ‘People suffer from dehydration, heat-stroke, burns from the fuel, but death comes in many forms unfortunately on this route’

They put out a Mayday call, to little effect.

El Manfalouti states: ‘You have a legal obligation to hand assistance to a boat in distress, to people whose lives are at risk, but that’s not happening. And that’s not happening because states refuse to take over coordination of these cases, so any vessel that might rescue people now is going to get stuck with them.’

Eventually, after several hours, the Mayday call to a nearby oil rig prompts one ship to move towards the boat, before suddenly a boat suspected of belonging to a Libyan militia group speeds up to the vessel in distress to recapture the people, prompting some of the passengers to jump in the water, preferring to die than go back to Libya. The passengers are forced onto the boat and likely escorted back to Libya.

In the documentary, El Manfalouti details: ‘What we see here is a result of a policy. This is not an accident, it doesn’t have to be like that.

‘Ten years ago, this would not have happened. Ten years ago, we had European navies, European coast guards, for example the German navy, Italian navy deploying active assets to get people out of the water. People would not have been exposed to the immediate loss of life for half a day, or a day or even longer. And crucially people would not have been brought to that vicious cycle of smuggling, human trafficking and the Libyan militia system. They would have been brought to a place of safety, extracted from that criminal environment in Libya, and Libyan militias would not have had a chance to cash in twice or thrice on the same human cargo.

‘They are returned to detention camps. There they either die from torture, malnourishment, preventable disease, or they cross again.

‘I think the most important thing that we’re observing is that thousands of people are losing their lives, because of these policy choices, year, after year, after year.

‘There’s a belief in European capitals that what happens at the border can be isolated, can be kept apart from what is happening domestically. But whatever happens in your borderlands, whatever is funded by your own taxpayers’ money, will sooner or later come back to haunt you. And I think we are already seeing this with the rise of the far right across Europe—an erosion of the rule of law. But the EU is in one way or another sustaining these human trafficking networks through its policy choices.’

On the EU side, Frontex, the EU border and coast guard agency, is increasingly linked to arms and security companies on the receiving end of the approximately €2bn budget.

Abolish Frontex points out that large European arms companies such as Airbus, Leonardo and Thales, are the biggest winners, positioning themselves as experts, taking part in advisory bodies and shaping EU border and migration policies and selling equipment and services to ‘combat’ the ‘security threat’ posed by those fleeing war.

Abolish Frontex goes on to point out the irony that these same arms companies export weapons to the very conflict zones people are fleeing.

‘Frontex and other border security authorities increasingly use autonomous systems for border surveillance. Over the last few years the agency has paid tens of millions of euros to arms companies Airbus, Elbit, Israel Aerospace Industries and Leonardo for providing drone surveillance services in the Mediterranean. This includes the use of so-called ‘killer drones’ which are promoted as ‘battlefield tested’ in wars and repression.’”

Furthermore, Maritime Frontex makes use of so-called border-externalisation operations, whereby third countries act as outpost border guards for the EU, stopping refugees before they ever reach EU shores. This practice directly legitimises and strengthens authoritarian regimes and their security forces.

In addition to the threat of Frontex’s practices, Libyan militia groups and the danger of being on open waters in unseaworthy vessels, the Greek coast guard has also long been accused of breaching international and European law by human rights organisations and NGOs.

On 7 January this year, for the first time, the European Court of Human Rights officially found Greece ‘systematically’ conducted illegal push-backs and ordered it to pay the victim of an illegal push-back conducted in 2019 a sum of €20,000.

The practice of push-backs and so-called ‘drift-backs’, whereby boats carrying refugees are towed further into the Aegean Sea and abandoned there, has been widely documented by NGOs and human rights organisations. The research agency, Forensic Architecture, has found that, between March 2020 and March 2023, the Greek coast guard pushed back 2,010 boats, endangering and risking the lives of some 55,445 people.

The systematic and widespread practise of endangering migrants’ and refugees’ lives again stands in stark contrast to the Geneva Convention, which declares: ‘Importantly, the Convention contains various safeguards against the expulsion of refugees. The principle of non-refoulement is so fundamental that no reservations or derogations may be made to it. It provides that no one shall expel or return (“refouler”) a refugee against his or her will, in any manner whatsoever, to a territory where he or she fears threats to life or freedom.’

With some 117 million forcibly displaced individuals world-wide, the highest number of people in search of safety on record, it is clear that global international security is waning and more people than ever need protecting.

However, the European Commission’s ‘ReArm Europe/Readiness 2030’ plan aims to unlock up to €800bn to incentivise increased defence spending among Member States, while the European Justice and Home Affairs council make amendments to harden European Asylum policies. Europe is demonstrating ‘shrinking political will and financial support for long-term investments in peace’.

Born out of a shared ambition to establish enduring peace after the Second World War, peace was one of the EU ‘s core values. Placed within its broader colonial legacies and resulting global inequalities, this means a truly secure Europe must prioritise inclusive dialogue, long-term conflict resolution, and human security, regardless of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.

This article is dedicated to Sultan, 19, from Sudan, who died last week during his second attempt at crossing the Mediterranean to seek refuge in Spain.