Germany’s New Tactics to Politically Cleanse Unwanted Dissident Voices

In the past month, the Berlin Immigration Office ordered three EU citizens and one US student to leave Germany after police investigations related to their activism in the Palestine Solidarity movement. As an investigation for The Intercept revealed, this occurred following a directive from the Berlin Senate’s Interior Department—even though none of those affected had been convicted.

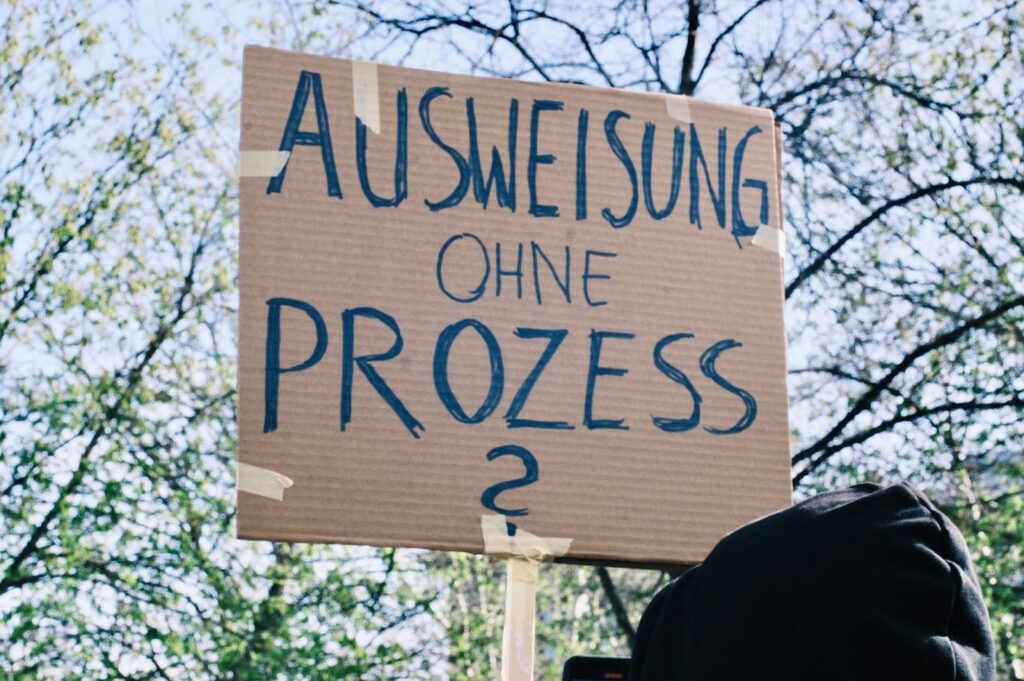

Rally “You Can’t Deport a Movement”, April 7, 2025. Translation of sign: “Expulsion without trial?” Photo by Nadine Essmat

In mid-March, the three EU citizens Shane O’Brien, Kasia Wlaszczyk, Roberta Murray, and US student Cooper Longbottom received notices from the Berlin Immigration Office, terminating their right to residence and ordering them to leave Germany by April 21; otherwise, they would face deportation. In addition, the Immigration Office issued a three-year entry and residence ban against the EU citizens and a two-year entry and residence ban for the Schengen area against US student Longbottom.

The four individuals have been investigated for separate charges related to their anti-genocidal activism in the Palestine Solidarity movement, such as trespassing, insulting police, resisting arrest, and incitement to hatred for chanting the slogan ‘from the river to the sea.’ The one severe and common accusation that connects them all concerns an alleged serious breach of peace for participating in the occupation of the Free University’s presidential office on October 17, last year. None of the individuals has been convicted.

Attempted Occupation of Free University’s Presidential Office, October 17, 2024. Photos: Nadine Essmat

While these are not the first expulsion cases following Palestine-related activism, the reasoning behind these particular cases and the circumstances around them are quite remarkable and raise major concerns about the rule of law and fundamental principles of democracy.

Departure Order without Conviction

The Berlin Immigration Office based the revocation of US national Longbottom’s student visa on German residence law. According to Sections 53 and 54, a foreigner without conviction can be expelled—after a complex balancing of considerations—if their residence poses a threat to the public order and security, the free democratic basic order, or to the security of the German state. The latter is assumed where there is reason to believe that the foreigner was a member of a terrorist organization or supported such an organization.

The Immigration Office considered the blanket police accusations against Longbottom in the FU occupation case sufficient proof of a threat to public order and security, despite the fact neither the police files specify what action Longbottom is accused of nor has the prosecutor filed an indictment against them.

In the cases of EU citizens Shane O’Brien, Kasia Wlaszczyk, and Roberta Murray, the Immigration Office invoked Section 6 of the Act on the General Freedom of Movement for EU Citizens, according to which there must be reasons for public order, public security, or health to terminate the entitlement of residence. The law also states that a criminal conviction alone shall not constitute sufficient grounds for the revocation and only insofar as the criminal action indicates a personal behaviour that constitutes a real and sufficiently serious threat to the public order, affecting the basic interests of society. Notably, Article 27(2) of the EU directive 2004/38 EC explicitly prohibits justifying withdrawal of residence rights on grounds of general prevention.

While the threshold for revoking residency rights of EU citizens is explicitly higher than for non-EU foreigners, the Immigration Office argued in the case of the three concerned EU citizens that a conviction was unnecessary. It deemed the blanket police allegations against them as sufficient evidence of a threat to state security. Notably, the Office classified the accusation of chanting ‘from the river to the sea’ as indirect support for Hamas—without providing further legal reasoning for this determination.

Invoking German Staatsräson

The Immigration Office also invoked the so-called German Staatsräson (German raison d’état) to justify a serious threat to the fundamental interests of the society, as provided in the EU Freedom of Movement Act. It did so by saying: “(i)n particular, Israel’s right to exist, its protection and the integrity of the State of Israel are German Staatsräson and, especially given Germany’s historical responsibility for Jews in Germany and Israel, are of great importance and particularly worthy of protection. It is in the considerable social and state interest that the German Staatsräson is filled with life at all times and that at no time – neither at home nor abroad – is there any doubt that opposing currents are even tolerated in Germany.”

The authority also used German Staatsräson to justify immediately enforcing the departure orders. Normally, revocation of residence rights does not require immediate departure; enforcement is typically suspended during pending appeals unless authorities demonstrate urgent necessity. In these cases, the Berlin Immigration Office asserted such urgency by declaring: ‘The continued presence of foreign nationals in Germany who—like the defendants—disseminate antisemitic and anti-Israeli hatred and hate speech against the backdrop of the terrorist attack on Israel by the radical Islamic group Hamas on October 7, 2023, must no longer be tolerated but ended as quickly as possible.”

The authority made no mention of the fact that the defendants were protesting Israel’s ongoing genocide in Gaza, in which more than 50,000 Palestinians have reportedly been killed, and for which Israel is on trial before the International Court of Justice.

Court Ruling in Relation to Urgent Appeal

The four individuals have appealed against the departure orders before the Berlin Administrative Court and filed urgent appeals against their immediate enforcement. As of the article’s publication date, the Court has only ruled on EU citizen Shane O’Brien’s urgent appeal, which it found successful.

On the matter of conviction, the Court agreed with the immigration authorities that a conviction was not compulsory for the revocation of his right to residence. This position is remarkable, as in another recent case of EU far right-wing politician Martin Sellner, the Potsdam Administrative Court rejected an entry ban to prevent Sellner from attending a far-right conference on „re-migration“ last year. The Court argued that the consequences of such a ban were so serious that it could not be assumed prematurely that there was a threat to public order and security. It came to a similar conclusion in the case of British-Palestinian doctor Ghassan Abou Sitta. It rejected the entry ban imposed on him in connection with the Palestine Congress last year.

However, the Berlin Administrative Court criticised the Immigration Office for its flawed examination of O’Brien’s case and found fault with its reliance solely on vague police accusations instead of requesting the prosecutor’s investigation files to examine them closely, particularly with regard to the concrete level of evidence.

The Berlin Court also criticised the Immigration Office for not stating in more detail which alleged actions of the defendant constituted a threat to the basic interests of society and to what extent. In this context, it emphasized that charges related to insult and violating the Berlin Assembly Act are considered of a lower criminal category and—even if they would have been committed numerous times—were not suitable to constitute a serious threat to the basic interests of society.

As for the accusations of using signs of terrorist organisations by chanting the slogan ‘from the river to the sea,’ the Court recalled that the legal assessment of that slogan is controversial among the courts and that Section 86a of the German Criminal Act falls under the lower criminal category anyway.

The Court, however, did not challenge or otherwise address the authority’s invocation of German Staatsräson. It is important to note that the nature of the Staatsräson is neither a law nor a legal concept but rather a purely political idea aiming at safeguarding the state’s interests. German Staatsräson asserts that the state’s primary interest is the security of another state. That alone seems bizarre and completely illogical.

The court decision on the remaining urgent appeals is still pending. In the meantime, the other three individuals concerned are protected from deportation.

Notification Orders by Political Command

What made The Intercept’s investigation particularly explosive was that the departure orders were issued following a political directive from the Berlin Interior Department, the supervisory body of the Immigration Office. The German NGO FragdenStaat published the internal email communication between the SPD-led Interior Department and the Immigration Office, which reveals that the Interior Department had ordered the authority to terminate the stay of the four individuals with immediate effect over their alleged involvement in the FU occupation. The immigration officer in charge refused to comply with these instructions, citing legal concerns from the head of the Immigration Office, Engelhard Mazanke, as none of the EU citizens had any criminal conviction, and the lawyer’s statement regarding US national Longbottom was still underway. The officer from the Interior Department responded “with astonishment” that the directive was not being complied with and upheld the order without further reasoning. The Immigration Office eventually relented and issued the requested departure orders against the four individuals.

Dangerous Trend

These circumstances and reasons given for the departure orders mark a new chilling low point of an already dangerous trend in Germany, in which the state seems to use common authoritarian tactics to eliminate unwelcome dissidents.

The statements of Burkard Dregger, policy spokesman for the CDU parliamentary group in the Berlin House of Representatives, expose this dangerous escalation when commenting on the departure orders to the Axel Springer daily news Die Welt: “These are criminals, and it is important to set an example when it comes to the so-called pro-Palestine demonstrations, which are, in fact, pro-Hamas demonstrations.”

Dregger’s statements constitute a clear infringement of fundamental principles of democracy and the rule of law. First, by defaming defendants as criminals and thereby disregarding the presumption of innocence enshrined in Article 6 of the European Human Rights Charter. The statements further reveal that deterrence is used as the state’s primary rationale for issuing the departure orders, while EU law clearly prohibits that. Furthermore, they frame peaceful demonstrations against the genocide in Gaza as support for the banned Hamas without further evidence—thus vilifying and criminalizing freedom of speech, while, by referring to the protests as “so-called pro-Palestine demonstrations,” the reader is conditioned to believe that Palestine doesn’t actually exist.

It is also not an isolated case in which an official was pressured to follow an evidently unlawful directive and according to an email correspondence published by FragDenStaat, the former FDP Education Minister Stark-Watzinger instructed officials from her ministry last year to compile a list of academics openly opposing the evacuation of the FU campus in May 2024 to withdraw state funding from them. The email correspondence further reveals that officials did raise legal concerns regarding this order.

But in particular, Germany’s increasing tendency to invoke political concepts like German Staatsräson and adopt non-binding resolutions- instead of passing their content through a proper legislative and democratic process – is a worrying authoritarian tactic aimed at encroaching on fundamental rights and freedoms through the imposition of measures that are otherwise legally untenable.

The critical point has been reached, where courts begin to legitimize these tactics as a potential legal justification for violating these fundamental rights. This is precisely what the Berlin Administrative Court did in the recent cases by not clearly objecting to the use of German Staaträson as a justification for expulsion. In the Shapira case, the Berlin Criminal Court went even further. It invoked the non-binding and controversial IHRA definition of antisemitism to justify a three-year prison sentence against a German-Palestinian student for dangerous bodily harm on the grounds that the defendant had an “antisemitic” motive; a punishment that even the prosecutor did not request.

The signs that Germany is transitioning to an authoritarian state are already evident. This shift is driven by the above events and trends, which appear to initiate a countdown toward arbitrary and politically motivated trials. That, in fact, seems to be the real and most serious threat to our fundamental interests as a society, one that we all must stand up and fight against if we don’t want to fall back into a new era of fascism.

An earlier version of this article was published on April 22 on the author’s Substack. The case has developed further. On May 6, the Berlin Administrative Court also upheld the urgent appeal of Irish national Roberta Murray, citing the same grounds as in Shane O’Brien’s case. This time, the Court additionally expressed concerns about using the concept of German Staatsräson as a justification to determine Murray’s loss of the right to free movement.