The sooty fingertips of climate change can be found on almost everything dominating the news these days: soaring food prices, weather disasters, severe disruptions of ecosystems. And with another summer afoot, its halfway point has already hit Europe with a sweltering, inescapable heatwave, causing thousands of deaths. Another effect that may not have been at the forefront of climate change experts’ and activists’ manifestos, is its negative impact on human health.

When we think of summertime, usually it’s turquoise water, poolside lounging, clear and bright skies. After all, things usually look better under a filter of golden glow. But there’s an aesthetic, and then there’s reality: rapidly rising temperatures, weather disasters, and lack of equitable and sustainable energy access spreading disease and deterioration—exacerbated by an unsteady health infrastructure and many countries’ sheer lack of climate resilient tools.

This year in June, the World Health Organization declared climate change to be a public health emergency. They’ve been emphasizing the danger it wields against humanity for years, pointing to rapid air pollution, an uptick in infectious diseases, and a surge of heat-related deaths. And yet, while climate change’s effect on health and mortality is well-documented and increasingly covered in the media, it still seems under-acknowledged in the general public sphere.

A rapid study led by researchers from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Imperial College London found that the pollution-driven warming tripled the death toll of Europe’s heatwave. A concerning 58% of infectious diseases faced by humanity worldwide have been in some form exacerbated by climate change. In December 2024, almost one fifth of Dengue cases in Latin America and the Caribbean were attributed to global warming, according to a study carried out by researchers at Harvard and Stanford. In 2023, a record number of six million cases of dengue fever were reported worldwide, indicating that as the world’s burning ramps up, so does disease. Malaria also has been linked to rising temperatures, due to parasites thriving in humid climates. WHO has also explored the intersection of tuberculosis (TB)—one of the world’s most contagious and dangerous diseases—and climate change, highlighting water insecurity and displacement as key factors.

Researchers urged for extreme heat to be appreciated as a very material threat, and one that will appear with increasing regularity, due to the relentless speed of global warming. Indeed, June 2025 is the hottest ever recorded, and all signs point to the remainder of the year following its example. While Europe, Africa, and Asia are scrambling to rein in carbon emissions and speed-run the green energy transition, President Donald Trump has slashed funding for a host of sustainability initiatives and just hired three climate contrarians for the United States Energy Department, indicating that the leading global power is standing firm on plans to burn more and more fossil fuels, all evidence of severe danger be damned.

Extreme heat isn’t the only threat climate change poses. This year alone, climate change has been linked to higher prevalence of eco-anxiety, sleep apnea, difficulties during pregnancy, a high prevalence of eco-anxiety, and the faster spreading of infectious diseases. From sleep conditions to mental illness, pollution touches every aspect of human health—and fundamentally, every part of our lives. And with every person affected, comes a further strain on an already-struggling healthcare system, the infrastructure of which is globally lacking due to aid cuts and general patient inequity.

The “Food is Medicine” initiative has seen a recent increase in popularity in the United States. Positing that nourishing, individualized diets and access to healthy foods regularly can combat a number of health issues and save the government a substantial chunk of change, philanthropic organizations and research associations worldwide are working to implement such projects. But climate change threatens this radically simple ambition by disrupting the levels of carbon dioxide and the temperature conditions required for optimal crop growth, and by causing an imbalanced water supply. The world food production rate and the nutrition values of foods have been gravely impacted as a result. Agricultural losses are being recorded with more frequency, in line with the changes to temperature and precipitation. Without affordable and healthy food, the power of nutrition and nourishment is reduced—and chronic illnesses flourish.

Perhaps coming on the heels of COVID, the general population is too fatigued to address another health emergency. After all, it was an odd, alienating and, scary time, impacting our mental health in myriad ways. In fact, reports confirmed that COVID drove wedges between people, threatening solidarity and community during a distressing time. It was almost four years of lock downs and regulations, some of which chopped and changed so quickly they had us all suffering from whiplash. Only five years have passed since it was declared, and yet, often in conversation, it is referred to in bafflement and abject incredulity. With the toll it took globally, it’s no wonder that there is a resistance to addressing another health emergency, one that isn’t new but has been bubbling barely beneath the surface for decades, over flames stoked by human-caused global warming. How could we not be jaded? Atop the succession of crises the past five years have offered us, those who aren’t denying climate change are also aware of the fact that it’s the top 1% of the world that emit the most carbon dioxide—roughly 1000 times more than the rest of us.

And yet talking about it is better than not, because any small drop into a rising wave can contribute to a revolution.

While the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP29) in Baku ended with a feeling of disappointment at the inadequacy of climate commitments, a milestone occurred in the signing of a Letter of Intent uniting Azerbaijan, Brazil, Egypt, the UAE and the UK under a framework co-led with the WHO with the aim of integrating health into climate change policies. WHO officials underlined health as a cross-cutting priority and emphasized that future leaders ought to keep the same momentum for the issue. COP30, slated for November in Brazil, is expected to continue on this line of discussion, with hopes that advances have been made and resilience is being pursued.

Of course, the Trump administration’s slashing of foreign aid has thrust many undeserving countries into a tailspin. Despite insistence that the cuts have not caused fatalities, CNN has reported from the Nangarhar Regional Hospital in Afghanistan, where US-funded medicines, medical equipment, nurses, doctors, and midwives have been withdrawn, that the mortality rate of babies has risen by three or four percent since the suspension. Further research has projected that the cuts of international humanitarian aid could cause fourteen million premature deaths by 2030—with a third expected to be children. But medical calamities aren’t just being outsourced to the world’s most vulnerable countries; that Big Beautiful Bill we keep hearing about (I believe the ink is still fresh) will have a profound impact on the country’s healthcare. “This big, beautiful bill—in terms of its impact on health care, on how physicians and hospitals are going to navigate the next few years—I think is the biggest immoral piece of health care legislation I’ve ever seen. Just unethical, indefensible and tragic,” Arthur L. Caplan, PhD, a professor and founding head of the division of medical ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine told Healio.

Himal Magazine has declared that the global health order as we know it has collapsed. This May, the 2025 Geneva Health Forum (GHF) took place alongside the World Health Assembly (WHA), under the theme of “One World for Health”—convening leaders in global health, medical personnel, philanthropists, and academics who were ensured of the utmost significance of the event—this year more than ever. In a session titled “Climate Change and Health: Adaptation and Resilience in a Changing World”, experts considered how to develop a new system, one in which climate change is recognized as a defining human health emergency.

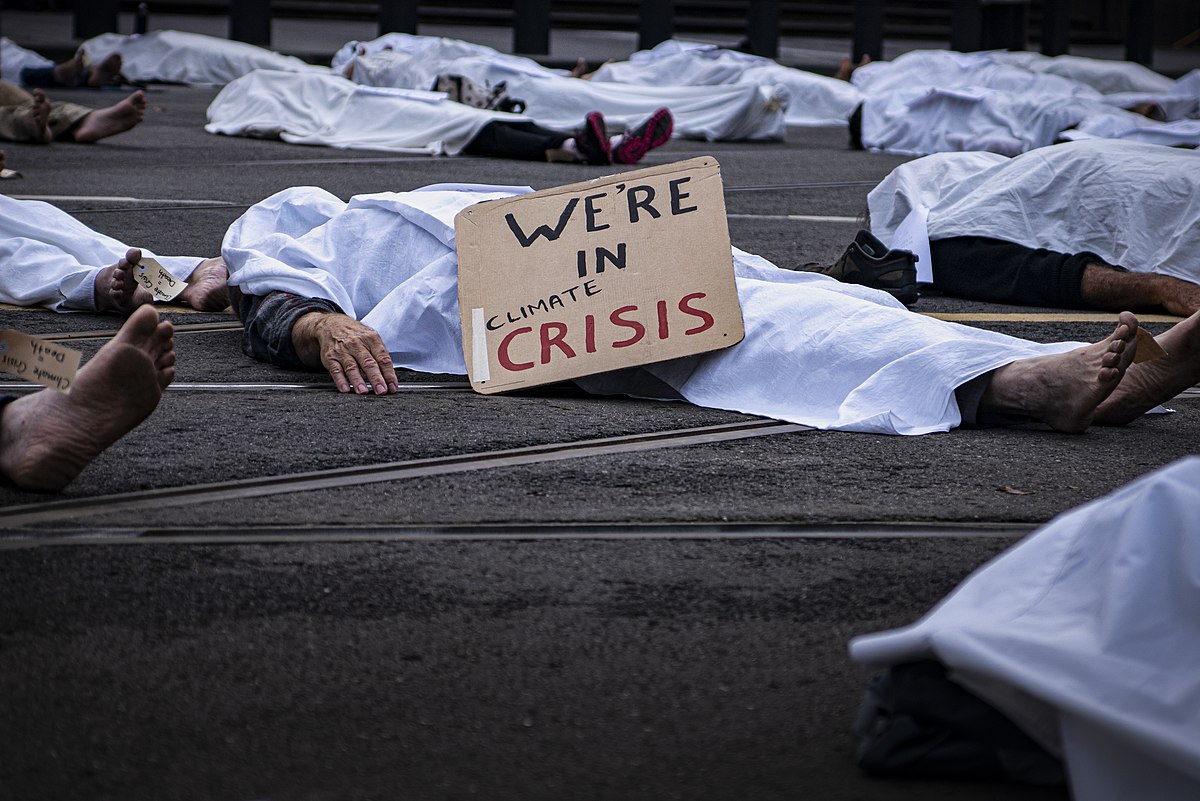

A burning planet scorches everyone in its path, but particularly the vulnerable. The elite set the bonfires and we inhale the smoke. The dam has already broken for those at the bottom of the pile—those who don’t have access to healthcare or food or shelter, those who are unable to afford nutritious meals or preventative care—and the water will rise until it reaches all of us. COP30 is coming in a matter of months, and the global health order is being recreated almost from scratch. While the only action most of us are able to provide to the cause is spreading awareness, it’s an action we must continue to do—continue talking, continue sharing, and continue protesting. Healthcare is at the point where it is now inextricable from climate change, and it’s imperative that research continues and measures are still taken towards crafting resilient and adaptable infrastructures worldwide to prevent millions of needless deaths.

Ellen McBride is an Irish writer, media analyst and social media marketer based in Berlin. She has written for Friends of Friends, Companion Magazine and Whisk Journal.