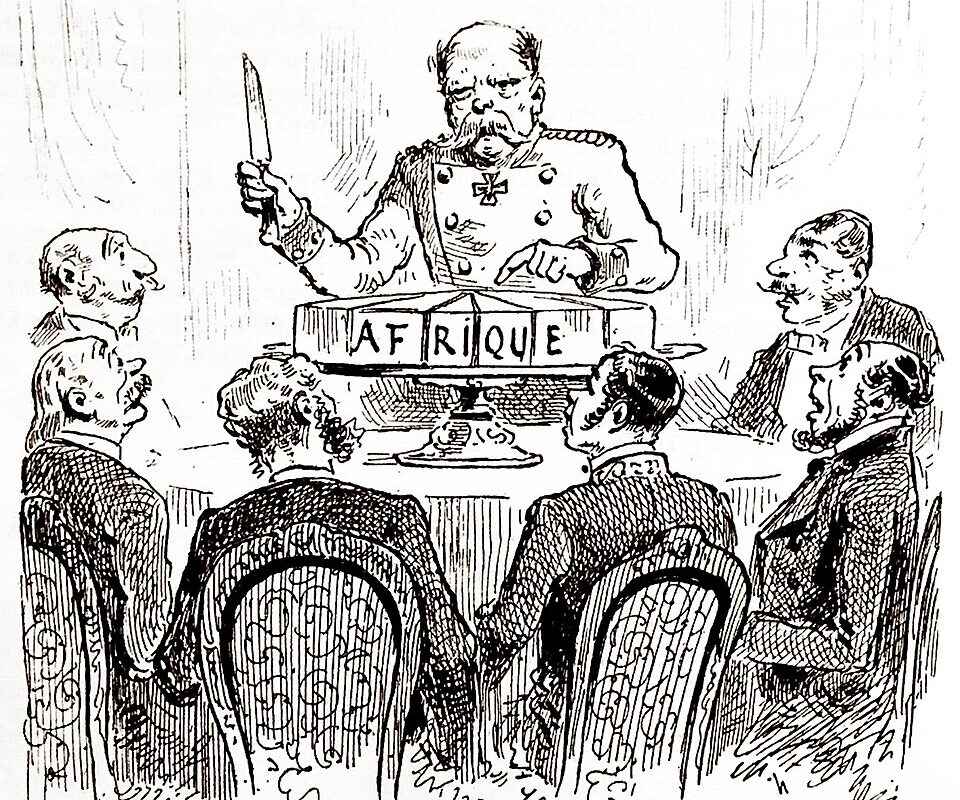

On 15 November 1884, Otto von Bismarck opened the Berlin Conference in his palace on Wilhelmstraße. The conference aimed to resolve the “Scramble for Africa,” in which Global North countries competed to control the continent’s mineral-rich resources. Nineteen delegates from fourteen countries attended, ranging from the United States to Tsarist Russia. Despite it sometimes being called the Congo Conference or the African Conference of Berlin, not a single African country was invited.

The conference redrew the borders of Africa. When it opened, only 20% of the continent was colonised. By the outbreak of the First World War just thirty years later, only Ethiopia and Liberia remained free. Ten thousand distinct communities were forced to live within forty separate occupied territories. Before the conference had even ended, Nigeria’s Lagos Observer reported that “the world had, perhaps, never witnessed a robbery on so large a scale”.

Colonisation was far from peaceful. South Africa saw the world’s first concentration camps, set up by British occupation forces. Germany followed suit in Namibia, where a German-organised genocide killed 80% of the Herero and Nama populations. Various methods were used to normalise colonisation to the German public: street names were dedicated to colonisers, and the supermarket Edeka took its name from an acronym for the Einkaufsgenossenschaft der Kolonialwarenhändler (Cooperative of Colonial Grocers).

The General Act of the Berlin Conference contained two key articles. Article 34 declared the “doctrine of spheres of influence,” allowing European powers to claim parts of Africa provided they informed the other nations beforehand. Article 35, the “principle of effective occupation,” stated that a country could acquire rights over colonial land by setting up a coastal base, as long as it promised to protect existing rights and freedom of trade—meaning the rights and freedoms of other imperial powers.

The attempt by the Great Powers to carve up Africa did not go unopposed. The Nandi waged a ten-year war in what is now Kenya, disrupting the construction of the Uganda Railway. Ethiopian resistance preserved the country’s independence until the Italian invasion of 1936. The Maji Maji rebellion in Tanzania between 1903 and 1907 was one of many local uprisings. Ultimately, however, European firepower overwhelmed local resistance. The divisions sown in Berlin endure to this day.